In 1900, Captain James V. Martin, the man at the centre of the American Relief Administration scandal, published an anti-Expansionist pamphlet sponsored by Andrew Carnegie and William Jennings Bryan. This story explores the unlikely hand of friendship extended by American Populists to Russian Revolutionaries at the time of the McKinley Assassination.

No one event, however sensational, can ever mark the end of something, just as no single episode can ever truly signal its beginning. But before we finish, I would like to provide a little extra context to the publication of Martin’s book, ‘Expansion: Our Flag Unstained’ in 1900 which featured ‘special contributions’ from millionaire Andrew Carnegie and 1896 Presidential Candidate, William Jennings Bryan.[1] It was in this book that the prodigious 17 year-old had very skilfully combined the fashionable theories of flag desecration with the hard, reactionary rhetoric of Revolutionary Socialism. It wasn’t an original idea. The actual phrase that Martin had recycled, “Our Flag Unstained”, dated all the way back to the mid-1800s when it appeared in discussions in Congress regarding the previous year’s controversial attack at Monterey in February 1843. [2] The same year that Martin published his pamphlet, the phrase would be repeated in a ‘Manual of Patriotism’ produced by Republican congressman, Charles Rufus Skinner, who just twelve months later would be a key witness in the assassination of President William McKinley by anarchist, Leon Czolgosz at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, New York in September 1901. [3] The battle over the flag’s symbolic value would continue with ‘Our Flag and the Red Flag’ in 1915, an isolationist, Socialist tract put together by Congregational Minister Samuel Salem Condo in an attempt to preserve American neutrality in the first few years of the war: “American children are brought up to believe that the stars and stripes represent freedom, justice and democracy. And when they are men they fight under that symbol, without a question, even when it is made to serve the will of capitalism, imperialism, tyranny and oppression” [4] Understanding the battle for control of the stars and stripes at a symbolic level, and providing some context to ongoing perceptions of the flag’s abuses during the period in which Martin published his work, is critical to understanding the polarising events that followed, as Martin’s co-sponsor Bryans was, you will remember, the 1896 running-mate of Populist and anti-Imperialist, Thomas E. Watson, the man who was to launch the Federal case against Hoover and the A.R.A in which Martin was called as witness. [5]

As mentioned previously, the bonds between the American anti-Imperialists and the Russian ‘anarchists’ of the late 1890s and early 1900s was especially strong, with exiles like Sergei Stepniak and Prince Kropotkin held in particularly high regard. Expressing his deep, personal regard for Stepniak at the Park Memorial Hall in January 1896 was Edwin Doak Mead, president of the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom. As on so many other occasions Mead was joined by the society’s treasurer Francis J. Garrison and noted abolitionist and revolutionary patriot, Julia Ward-Howe. Even if you don’t know her name, you’ll know the name of the tune that Ward-Howe had written, featuring as it has on everything from cowboy and cavalry movies to the inauguration of Donald Trump in January 2016. The song she composed was The Battle Hymn of the Republic. Think of John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave and you’ve got it nailed, as this was a civil-war rewrite of the same tune by Ward-Howe. During the American Civil War it was a favourite at camp meetings, and, perhaps ironically given its links to the Russian anarchists, the song was being triumphantly belted out by the followers of Donald Trump as they stormed the Capitol Building in January 2021.

By this point in time, Kennan was well and truly established at the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom with his ally, Francis J. Garrison. His lecture tours regularly trotted out figures about Tsarist spies operating in Europe and America, with some estimates ranging in excess of 1, 300, 000. Suspecting Russian spies to be among the audience at the packed out auditoriums, Kennan was to make a point of guarding the names of political prisoners he had talked to in Siberia, with the ‘blood-curdling revelations’ he was prohibited from repeating only adding to the climate of terror. The excitement and sense of urgency the claim must have created in the theatres would have been nothing short of electric. Re-centering the nihilist’s struggle within the discourse of international suffrage, where it could be seen to be driven by the natural pursuit of happiness rather than lawlessness and disorder, would certainly have been an attractive goal.

Garrison’s father was the crusading abolitionist and publisher, William Lloyd Garrison, whose Liberator journal had not only become a prominent voice in the anti-slavery movement but had also helped sharpen the resolve of women’s suffrage and the anti-Imperialist movements in America. The daughter of a Wall Street banker, Julia Ward-Howe, one of the leading flag bearers of the Russian Freedom movement, was herself a descendent of a hero of the American Revolution. To all intents and purposes the movement was about as American — and revolutionary — as it got.

That the anarchists under Goldenberg and Stepniak had burrowed their way into the bosom of the anti-slavery and Republican Patriot movements was made abundantly clear in a statement prepared by writer and historian Edwin Doak Mead in June 1899:

“As to Stepniak’s doctrines, they were to me as American and a Republican, mild and inoffensive enough. Having heard a great deal of wild talk about Russian ‘Nihilism,’ it was to me something of a surprise that Stepniak and his friends demanded in Russia nothing beyond what all of us in America consider primary political rights. Indeed, he did not demand so much a republic; he demanded only some honest form of representative government; some way in which the people could fairly be heard, and make themselves fairly felt in government.” [6]

Any fantasies you might have of the 70 year-old Ward-Howe constructing pipe-bombs and lobbing dynamite may need to be revised as this was a wholly respectable affair. The soul and energy of the society had always been driven by a moral obligation to expose and condemn the grotesque brutalities of Tsarist tyranny and its uncivilised punitive system to a respectable Western audience by all ethical and legal means. This was not a terrorist organisation in deed or in spirit. The Revolutionaries were for a time at least successful in knitting their various political and fund raising missions into the civilised fabric of American Patriotism and Progressive Social Reform. Cash was a finite resource, upon which a revolution could be prepared, but it was public sympathy that kept it going and the group were on the look-out for investors on both fronts. The twin issues of Immigration and Social Justice would inevitably become the focus of some deep well-drilling.

United by mutual bonds of patriotism and justice, the SAFRF was rolled-out exclusively as a pressure group, calibrated to arouse the utmost sympathy among Americans. This was about self-determination — the very bedrock of American Republicanism. And the men and women recruited into its services shared the same fundamentalist mindset when it came to rooting out greed and corruption. The basic composition and will of the group was already there. Stepniak’s arrival at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City in January 1890 simply formalised what was already happening. [7]

By the mid-1890s, things had begun to change. The movement which had been born of mutual moral standards, patriotic values and a pursuit of liberty began to inherit and develop concerns about the economic and social injustices, the remits of slavery moving from issues of colour to those of wages. A virus had been unleashed.

The change in tack wasn’t unprecedented by any means. At an address made at a memorial service at the Cooper Union Building on March 19th 1883, the Brooklyn-based journalist, John Swinton, had already done much to bind the civil war metaphors and inspiration provided by Julia Ward-Howe with the first slender cords of International Socialism. Tonight he went one further, by comparing Karl Marx to the infamous Civil War abolitionist, John Brown. Over the course of the evening, the crowded assembly room had heard speeches by P. J. McGuire, Victor Drury and Johann Most but it was Swinton who left the biggest impact. Introducing his speech with a graphic description of his last meeting with Karl Marx in Ramsgate, England, Swinton went on to claim how the recently deceased Socialist had made the Internationalé the watchword of the world’s workers. Marx was, he contested, no less a martyr than the likes of William Lloyd Garrison, Richard Emmet, and John Brown. The evening was rounded off with the reading of telegrams from Henry George and Frederick Engels. [8]

Thirty years later, Swinton and Stepniak advocate, Edwin Doak Mead would become a founding member and early trustee of the World Peace Foundation. The group would bequickly rivalled by the hastily convened and more Conservative, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, founded that same year by Martin’s co-sponsor, the millionaire businessman and philanthropist, Andrew Carnegie. If Mead’s 1899 tribute to Stepniak tells us anything it’s that there were many Americans within the Russian Freedom movement who had a very poor grasp of anarchist theory. Was Stepniak really just demanding some “form of representative government”? Certainly compromises were being made with the Parliamentarians in the Socialist movements, but the core principles of revolutionary anarchism being promoted by the likes of Kropotkin and Stepniak were quite the opposite: direct action and solidarity, anti-parliamentarianism, expropriation and insurrection. There was, however no doubting that the core ideology of American Republicanism — the preservation of inviolable civic rights, the rejection of monarchy and hereditary power, the vilification of corruption, the commitment to liberty — was something that both groups shared. In this respect and in this respect alone, Kropotkin and Stepniak were not unlike Mead’s ‘Founding Fathers’.

The appalling scenes witnessed at Capitol Building in January 2021 had clearly been driven by doubts and concerns that have been rattling on for centuries. Even back in Mead and Swinton’s day, the lack of faith in the parliamentary system that underscored the US Senate was certainly not confined to anarchists, but to ordinary voters and American patriots. The ‘tyranny of the majority’, described in excruciating detail by the North American Review in January 1867, was a fear that both groups shared — the fear that unpopular minority voices would eventually be overwhelmed by the excesses of pure democracy, their own rights stifled and eventually terminated by the power of the ‘legislative majorities’. It was a sentiment that Senator James A. McDougall would describe that same month:

“The majority had lost all regard and all respect for the feelings and wishes of the minority. The opinion of every senator on this floor was formerly listened to, but now in these days of caucuses, they had no rights whatever … Now everything was determined there. The tyranny of the majority was worse than the tyranny of the howling mob”. [9]

In December 1906, the ‘Murder League’s’ Grigory Gershuni — the latest anarchist celebrity to win grace and favour at the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom — took to the stage of the Carnegie Hall on Seventh Avenue in mid-town Manhattan, New York. News of the Socialist revolutionary’s daring escape from the quicksilver mines at Akatul in Siberia in a sauerkraut barrel had stirred American hearts. From Japan he had made his way to New York where he received a rapturous welcome from a crowd of 5,000 in an event organized by the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom’s Paul Kaplan. Whether Ambassador James Bryce had a hand in securing the choice of venue from his old friend Andrew Carnegie is difficult to determine, but within twelve months, the thirty-five year old Gershuni would earn himself a sizeable chapter in Heroes and Heroines of Russia written by British Russian exile and reformer, Joseph Prelooker the following year. Prelooker’s thrilling account of Russia’s most illustrious revolutionary Titans described Gershuni as “the most dreaded of all the implacable enemies of Czarism”. [10] Gershuni had begun his career as a reformer, devoting himself to the spread of elementary education among Russia’s labouring classes before attempts on the lives of the head of the Russian Orthodox Church and Prince Obelensky, the Governor of Kharkiv in the north of the Ukraine, saw him sentenced to lifetime imprisonment in Siberia. Even prior to his miraculous escape, Russian authorities had begun to regard Gershuni with an almost “superstitious fear” believing him to be in possession of superhuman power that allowed him and his murder league to carry out their various hits so swiftly and so confidently. Paying tribute to his means of escape and the salvation it offered to Russian people, Abraham Cahan, the editor of The Forward newspaper, suggested replacing the sign of the Christian cross with the emblem of the barrel. [11] Among Gershuni’s most enthusiastic supporters that night in New York was anarchist Emma Goldman and her husband, Alexander Berkman, recently released from prison after serving a 14-year sentence for an attempt on the life of Henry Clay Frick, the former business partner of the venue’s owner, Andrew Carnegie.

Carnegie himself was something of a contradiction in terms. Born in Dumfermline in Scotland, he had risen from being the son of a poor weaver to one of America’s most dynamic millionaires, his immense wealth and political influence arising from a passionate ‘can-do’ attitude and an instinctive appreciation of progress and innovation. In addition to qualities like these he had a rather unique and not exactly logical social consciousness, leading to some of the grandest gestures of philanthropy and some of the most ambitious global peace projects. It was a life lived constantly trying to reconcile the immense healing powers of wealth with its more rapacious impulses, impulses that for many provided the basic fuel of capitalism, and which consequently drove progress. His views on the relationship between capital and labour were complex and frequently overwhelmed by his responsibilities to the common worker. The strategies and values maintained by his partner Frick on the otherhand were not quite so unambiguous: when trouble arose it needed smashing. The ‘Darwinesque’ Carnegie had met his match in the pugnacious catastrophism of Frick. For Frick, survival was based more on short-lived violence and mass extinction than it was on discussion and negotiation. One was about evolution and the other about domination.

At the time of the incident, relations between Frick and Carnegie were rumoured to be at an all-time low, the latter having tried a number of times to remove him as Chairman at Carnegie Steel Company. It came to a head that June when Frick’s heavy-handed tactics during a strike at their Homestead steel plant had left nine union workers and seven security guards dead. Energized by his association with the anarchist organization, Pioneers of Liberty and his highly mobile strike-force, Berkman was intent on responding as only any self-respecting anarchist could. He hooked-up with a couple of anarchists from the Homestead steel plant and made a beeline for Frick’s office with a dagger and revolver. His attempt was a total failure. The pair had struggled and the blows struck were not fatal. Just weeks after Berkman’s sentence was announced, Boris Reinstein[12], the man who had assisted Russian revolutionaries Vladmir Burtsev and Aleksei Teplov in the ‘Paris Bomb Plot of 1890’— and who would later serve directly under Trotsky in Soviet’s Military and Naval Affairs — landed in New York where he quickly set about filling the gap in the agitation movement left by the 21 year jail term awarded to Berkman. [13]

It wasn’t the first time that the Carnegie Hall and its founder Andrew Carnegie would end up propping up the flourishing anarchist industry in New York. This was a critical time for America. A new century had meant a new narrative. The staggering volume of refugees arriving from Southern Russia and Eastern Europe by boat each month was putting its ‘Land of the Free’ pledge in some serious moral jeopardy. The inscription written by Jewish activist Emma Lazarus and placed on a modest bronze plaque on the pedestal of the towering colossus at Liberty Island describing the promised lands of America as “the wretched refuse of your teeming shore” were in need of some subtle revision. Whilst America was still opening its doors to the “tempest-tossed” and “homeless” as it had always promised, the White House was under increasing pressure to limit the relentless influx through a series of new regulations. The watershed moment came on April 17, 1907, when some 11,747 hopeful immigrants arrived at Ellis Island. In an effort to preserve the true egalitarian spirit of its founding fathers the anarchists found themselves in the unlikely position of becoming America’s most zealous and ardent patriots. During this momentous period in US history two new conflicting narratives would begin to emerge, both of them based in two comparable, but ultimately irreconcilable ideas of preservationism and protectionism. On the one hand we had President McKinley’s deeply contentious tariff, which increased duties on all imports by almost 50%, and on the other we had the open embrace of American Patriots determined to protect the constitutional rights of liberty and freedom. The chimera that emerged was a narrative based on the need to preserve the basic freedoms of the nation by a more a systematic and more tightly regulated immigration policy. The part played by human rights would rather speedily be displaced by ‘protective’ legislation promising to minimize disruption and preserve a cultural equilibrium that would defend the rights of immigrants against the rising tide of anarchy and authoritarian socialist states.

The world’s most famous anarchist, Prince Peter Kropotkin might have turned down Carnegie’s personal request to meet him during his American tour of 1897, but any ill-feeling that had arisen over the attempted hit on Frick and the rough handling of the Homestead workers, eventually abated as Carnegie began to reveal his Socialist-lite agendas. The scale of the climb down was such that by December 1912 the Carnegie Hall was playing host to the veteran anarchist’s 70th birthday celebrations, in a lavish celebrity ‘do’ that had been organised by none other than Emma Goldman and her recently paroled husband Alexander Berkman. Just three years earlier, Goldman and Berkman had used the same venue to denounce the execution of Spanish revolutionary, Francisco Ferrer. To cries of “down with the church” and “down with Alphonso” Goldman and her husband had led their 600-strong band of Socialists up and down Madison Square and Fifth Avenue after a preliminary meeting at the famous hall. With red banners draped in black, Emma and the protesters expressed their hope that the shots that had killed Ferrer would inspire the world’s revolutionary proletariat to take up arms against the capitalists. [14]

But it wasn’t all screaming and shouting by any means. Carnegie, by this time a rather batty and dishevelled septuagenarian, was responsible for having commissioned the Ukrainian composer, teacher and pianist Platon Brounoff to provide a new star-spangled national anthem for New York’s newly formed People’s Choral Union. The tune — ‘America, My Glorious Land’ — was performed under the direction of Frank and Walter Damrosch in a sumptuous choral display at Carnegie Hall shortly after completion. The move was very much made with anti-restriction bill motives in mind. And it couldn’t have been better conceived, both in the fabric of its message and its choice of messengers. When the San Francisco Call newspaper went to press on May 15 1896, it was careful to place a report on Brounoff’s debut, and his purpose-written overture in the very next column to an update on the US Senate’s contentious Alien Restriction Bill. [15] The performance of the song, copyrighted in March 1899, was duly repeated in a concert at Ellis Island. [16]

A pupil of Anton Rubinstein and Rimsky-Korsakov, Platon had immigrated to the US in July 1891, after a spate of anti-Jewish violence in Elizabethgrad in Central Ukraine. Despite his prodigious range of talents, he had found it difficult to make his mark. He had sung and played at hundreds of concerts free of charge — Russian songs, Zionist songs, socialist songs, songs of freedom and songs of Israel — but had always felt hindered by his new home’s classical elite. By 1911, he had written a full American Opera. The opera, expressed for the most in Native American rhythms and idioms ended his brand new National Anthem.

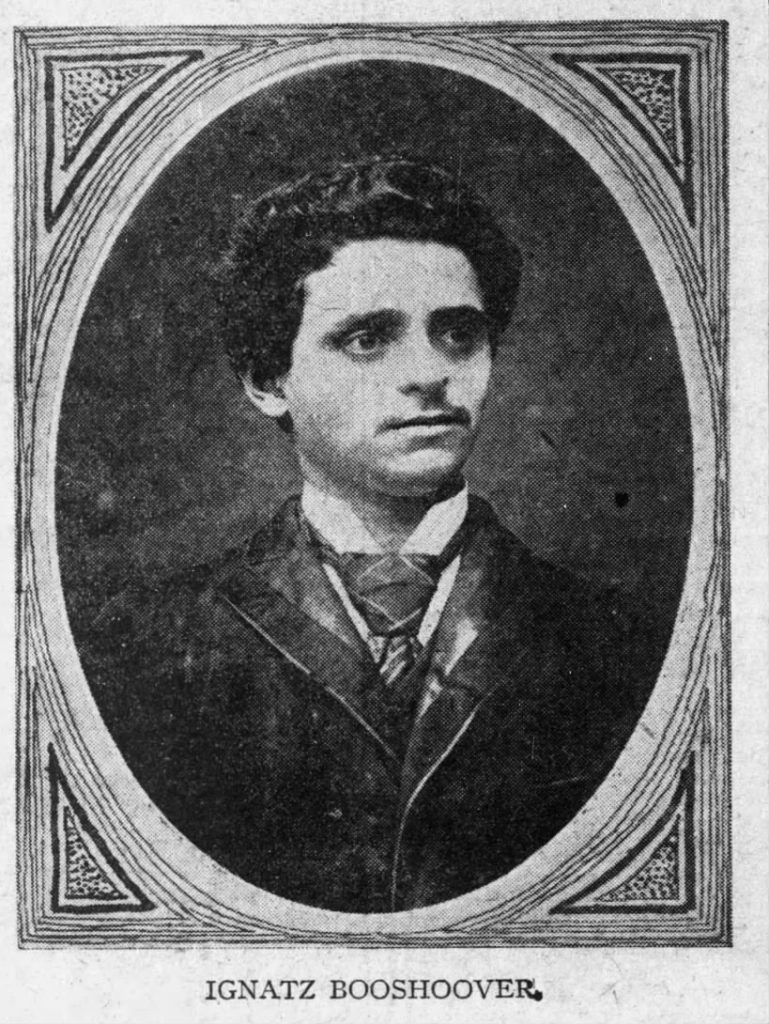

In an interview with the New York Times in 1911, Brounoff put his continued failure to become a mainstream sensation down to his furious activity on the Russian and Ukrainian archipelago on New York’s Lower East Side. This is where he’d focused his initial energies and it was ostensibly the source of his failure to take root in the popular consciousness. [17] The man who provided the words for Brounoff’s tune was Joseph Bovshover, a recent immigrant, and a man who Emma Goldman would later describe as a man of “exceptional poetic gifts”. [18] Within weeks of its reception at Carnegie Hall, the pair would send a copy of the song to the soon-to-be assassinated 25th US President, William McKinley. McKinley thanked him for their efforts, saying he had found the hymn inspiring.

Like Brounoff, Bovshover was a recent immigrant, but the pair’s backgrounds couldn’t have been more different. Brounoff was a graduate of the St Peteresburg Conservatory for Music and Bovshover was just a poor Yiddish poet from an Orthodox Jewish family in Lubavitch near Mogilev in modern day Belarus. Brounoff had spent the best part of his life trying to assimilate into Russian culture whilst Bovshover had been under enormous family pressure to maintain his Jewish roots and a defiant separatist outlook.

Shortly after arriving in America, Bovshover had found a furrier’s job in Brooklyn. [19] It wasn’t ideal but it was a start. The violence he’d witnessed back in Russia however had already begun to sharpen his intellectual and political instincts. With words flying like bullets from the barrels of revenge poetry he’d been stock-compiling during his youth, Joseph, quite understandably, became immersed in the local anarchist movement, and set-out writing verse for the profusion of freedom newspapers springing up the Lower East Side. Among the titles that published his work were Benjamin Tucker’s bi-weekly Liberty and the Yiddish Freye Arbeter Shtime (Free Voice of Labour). One of his poems, ‘Plenty’ reprinted in Britain’s Freedom journal in March 1897, combines all the energy and promise of early spring with the harvest time of retribution that inevitably follows. He has landed on ‘thirsty ground’ so to speak. The rich, fertile soils of America have led to the ‘ripening’ of his fury and one way or another, those little green shoots he writes so vividly about look set to emerge. [20] By 1899 things were looking good. Ukrainian Jacob Adler, a friend and colleague of New York theatre director David Belasco, staged Joseph’s translation of The Merchant of Venice for the People’s Theatre and a Broadway debut was looking imminent. [21]

Sadly, Joseph’s harvest-time wasn’t to last. In 1901 the talented poet was admitted to an asylum. An unknown friend was alleged to have seen trouble brewing and had the troubled poet committed against his will. His death in the institution some 15 years later was a cruel and tragic ending to a dream of infinite promise. His song, ‘America, My Glorious Land’ would subsequently be sung at both the White House and Capitol Building.

Strangely, Bovshover’s admission to an asylum came just several weeks prior to the assassination of President McKinley in September 1901. [22] The man who shot the President was Leon Czolgosz, an immigrant steelworker with fiery anarchist blood rushing like lava in his veins. Given that McKinley was shot at an event in Buffalo, one can only wonder if the assassin had links to Buffalo resident and worker’s leader, Boris Reinstein, the rehabilitated ‘Paris bomber’ who had arrived in Buffalo within months of Joseph Bovshover disembarking at Ellis Island. All three men certainly had links to Emma Goldman who was duly investigated but then cleared due to lack of evidence.

Reflecting on a possible link between Reinstein and President McKinley’s assassin is not entirely without merit. The hotel at 1078 [23] Broadway that Czolgosz had checked into on his arrival in town for the killing was just several yards from Reinstein’s home and chemist shop at 521 Broadway. [24] Czolgosz had moved to Buffalo for unspecified reasons some months before. Investigators were also able to establish that the hotel owner and Czolgosz’s cousin, John and Walter Nowak were prominent figures in Buffalo’s Socialist and anarchist circles — as of course was Reinstein. That said, one can’t dismiss the possibility that the killer’s decision to lodge at the hotel had been an attempt to keep the maximalist revolutionary Reinstein out of the picture and put local anarchist hotheads John and Walter Nowak in it. Perhaps Reinstein, now playing an active role in the American Socialist Party, needed them out of the way to raise his profile locally and seize control of the worker’s movement.

The venue chosen for the attack was, perhaps unsurprisingly, the Temple of Music, some five miles north of where McKinley was staying — an auditorium and concert hall that Bovshover’s co-writer Platon Brounoff would almost certainly have been familiar with. Like Bovshover, Czolgosz was also known to have expressed strong patriotic sentiments about America and the beacon of liberty it was so often praised for being among its immigrants.

It’s also intriguing to note that Bovshover is likely to have come into contact with associates of Goldman’s husband Berkman through the Orchard Street meetings of the Freedom of Pioneers group, an irregular symposium of speakers and writers loyal to the anarchist movement. Had Bovshover been committed to the asylum for threatening to blow the lid on the McKinley assassination? Had he been selected by the ‘murder league’, only to have buckled and tried to escape at the last possible moment? Just who did have Joseph committed?

From even a cursory review of the sequence of events it’s not difficult to see how America’s political and industrial rivals could have been channelling the furious energies of the bright young anarchists into fulfilling some murderous scheme that might help shift the power balances. All you needed was their trust, and all they needed was your cash and influence.

As leaders of the Anti-Imperialist League, Carnegie and William Jennings Bryan had had McKinley in their cross-hairs for years. Funded by Carnegie, Bryan had run against the President in the election race of 1897, and attempted the same thing again in 1901, his autocratic and brutal stance during the Filipino–Spanish-American War, having won him few admirers among the Spanish and Filipino anarchists already.

Some twenty years later the same James V. Martin, now an aviation pioneer and ship’s captain, would blow the whistle on American plans to smash the Bolsheviks at the height of post-war trade negotiations with the Soviet. As a result of Martin’s claim, Herbert Hoover was to be drawn into a deeply embarrassing profiteering scandal that lasted for some several years. The man who had initiated the charges against Hoover in senate was left-Wing agrarian Senator Thomas E. Watson — Bryan’s Presidential running-mate in the Carnegie-backed election of 1896, run, as you might well have anticipated, on the Anti-Imperialist ticket.

In March 1907, George Kennan, the adventurer who had done more than any other American to set the universal principles of Russian anarchism firmly within the mechanisms and culture of US Social Justice issues, supported an address made by Boris Reinstein’s fellow ‘Paris bomber’, Alexis Aladin and Nikolai Tchaikovsky.[25] As on previous occasions the address was made at the Carnegie Hall under the auspices of the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom. Those who had reserved boxes at the theatre that night included Joseph H. Schiff and novelist Mark Twain — Bryan and Carnegie’s co-founder at the Anti-Imperialist League. Among those who purchased regular tickets that evening was Alexander Berkman. Within 24 hours of the event, Berkman’s wife Emma Goldman would leave New York for a series of lectures in Chicago, St. Louis and Toronto, Berkman staying in New York to manage the affairs of Goldman’s journal, Mother Earth.

It was an extraordinary situation. After insisting on the pay reductions that led to Berkman shooting Frick, Carnegie’s name and reputation had found themselves being knitted into the rising tide of anarchy and the aspirations of the very people who had fired the fatal shots. As much as he subscribed to the notion of the survival of the fittest, Carnegie had begun to flirt with the idea that the answer to the world’s woes was no longer evolution but revolution — a seismic change in the order of things. The remedy for the pandemic of inequalities causing such grief and misery in the world was opportunity. As Carnegie saw it, the vaccine was in empowering the individual, and by helping himself he would help others. A more equitable distribution of wealth would bring about “the reconciliation of the rich and the poor” that so many dreamt of. If a mechanism could be put in place that ensured that the wealthy distributed their wealth more evenly, then the violent transfer of wealth to the masses, envisaged by the Socialist planned economies, would never be required. He wasn’t totally with the anarchists, but he was with them up to a point. [26]

His decision to write ‘Wealth’ for the Northern Review came as a response to the ‘Millionaire Socialist’ headlines being run by newspapers like the New York Times just a few years before. In the last weeks of December 1884, he’d attended a meeting of the Nineteenth Century Club. With him that evening was Brooklyn-based journalist and Marx supporter, John Swinton. Writing of the event in his own newspaper a few days later, Swinton had declared Carnegie a Socialist. Carnegie subsequently talked to New York Times as a way of qualifying his support. Yes, Swinton was present at the meeting, and yes he did speak of social inequality. It was clear to him that working men must keep on rising as they had in the past. Socialism was “the grandest theory ever presented” and would one day rule the world. The men of the future would be willing to work for the general welfare and share their riches with their neighbour. Asked by the reporter if he was willing to divide his own wealth, he said he wasn’t. [27] It would soon become clear that the anarchists could share his vitriol, but they weren’t going to share in fortune. The anarchists wanted one thing, Carnegie wanted another, but if they wanted to destroy the State, then they could at least destroy the State in a way that was favourable to his own unique vision. Martin and Carnegie’s 13,000 word challenge to ‘Tyranny and Oppression’ may have come in response to the annexation of the Philippines, but its sentiments reached much deeper into the US consciousness.

[1] The Democrat Bryan ran against Ohio governor William McKinley, assassinated by anarchist, Leon Czolgosz, in 1901. Bryan’s running-mate was Thomas E. Watson.

[2] Diario del Gobierno (letter dated 7th of January 1843), Doc No. 166, Taking Possession of Monterey, 27th Congress, 3rd Session, February 22 1843, p.16, Trade and Intercourse, Senate of the United States, Gales & Seaton, Washington D.C,

[3] Manual of Patriotism (for use in the public schools of the State of New York), Brandow Print Company, New York, 1900, p.7. See also: ‘Story of McKinley’s Assassination’, Skinner, Charles R. State Service April 1919 v3 n4, pp. 20-24

[4] ‘Our Flag and the Red Flag’, Samuel Salem Condo (author and publisher) 1915, p.15

[5] Thomas E. Watson would eventually take issue with the ‘One World’ Internationalism espoused by Carnegie, viewing his most cherished ideal, the League of Nations as nothing less than an Imperialist alliance.

[6] Free Russia, vol.10, no.6-7, June 1899

[7] ‘A Lecture in a Worthy Cause: Sergius Stepniak to Tell of the Russian Social System’, New York Times, December 20, 1890, p.8

[8] ‘The American Commune’, Bloomington Weekly Pantagraph 23 March 1883, p.4

[9] Richmond Daily Dispatch 19 January 1867, p.6

[10] Heroes and Heroines of Russia; Builders of a New Commonwealth, Jaakoff Prelooker, Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton & Kent, 1908, p.306

[11] ‘Greeted as “the Russian Lincoln” in Carnegie Hall – Czar’s Despotism Denounced’, New York Times 15 December 1906, p.2

[12] ‘The Arrest of Anarchists in Paris’, The Times, May 31 1890, p.7; ‘The Nihilists Arrested in Paris’, The Times, June 2 1890, p.5; ‘Trial of Nihilists in Paris’, The Times, July 5 1890, p.7; Vladimir Burtsev and the Struggle for a Free Russia, Robert Henderson, Bloomsbury Academic, 2017, pp.27-28.

[13] In 1917 September 1917 Reinstein was involved in a hotly disputed trip to the Third Zimmerwald Conference held in Stockholm with Max Goldfarb. Despite the best efforts of the Department of Justice to revoke his passport and prevent his trip to Russia, Reinstein eventually set sail in June with Slav passports on a Danish steamer. The department had acted over fears that his trip had been arranged to coincide with the trade meeting with Kerensky organised by Elihu Root and several senior US bankers and that attempts were being made to disrupt it (New York Times, May 10, 1917, p.8).

[14]Anarchist Socialist parade for Ferrer: Led by Emma Goldman, Marchers Cry” Down with the Pope!”, New York Times, 24 Oct 1909, p.8

[15] San Francisco Call, May 15 1896, p.2

[16] Catalog of Title Entries of Books Etc. Jan 5-March 30 First Quarter 1899 Vol. 18, Library of Congress. Copyright Office, p.528

[17] ‘Platon Brounoff, Composer, After Writing American Opera, Finds Difficulty in Getting the Musical World to Listen to It’, New York Times, January 22, 1911, p.15

[18] Living My Life, Vol.1, Emma Goldman, Anarchist Library, 1931, p.47

[19] https://yiddishkayt.org/view/joseph-bovshover/; http://yleksikon.blogspot.com/2014/10/yoysef-joseph-bovshover.html

[20] Freedom, 01 March 1897, p.5

[21] Joshua Fogel, yleksikon.blogspot.com, Oct 14 2014.

[22] Galveston Daily News 21 October 1901, p.6

[23] Complete Life of William McKinley, Marshall Everett, 1901, p.71

[24] 12th US Census, June 1900, Schedule No.1, Population, 521 Broadway, Boris Reinstein (b.1866, Russia), Anna Reinstein (b.1866, Russia), Wadina Reinstein (b.1888, Switzerland), Vider Reinstein (b.1894, New York); US Passport Applications, Jan 2 1906-March 31 1925, Boris Reinstein, 1907 application, NARA Publication No. M1490, Roll No.42, FindMyPast; Eleventh Annual Announcement of the Buffalo College of Pharmacy, Dept. of Pharmacy, University of Buffalo, p.40

[25] ‘Won’t Talked Masked, Alexis Aladin Says, Russian Revolutionists Won’t Answer Official’s Charge of Anarchy’, New York Times, March 17, 1907, p.7

[26] ‘Wealth’, Andrew Carnegie, The North American Review, Jun., 1889, Vol. 148, No. 391, Jun., 1889, pp. 653-664

[27] ‘Millionaire Socialist’, New York Times, 02 Jan, 1885, p.1