The Original Russian Job: The forgotten story of how a ‘secret compact’ between Churchill and America very nearly saved Russia from Lenin and the Soviet Union. This is the story of James V. Martin, an aviation pioneer who blew the whistle on American plans to smash the Bolsheviks at the height of post-war trade negotiations with the Soviet. It’s a tortuous, complex tale of political manoeuvring, espionage and high-stake deals performed in the utmost echelons of power, featuring such legendary figures as Sidney Reilly ‘Ace of Spies’, pioneer aviator Glenn Curtiss, William J. Donovan and an unscrupulous consortium of bankers, bluffers and brokers.

Listen Podcast of the ARA Scandal

The Secret War Compact

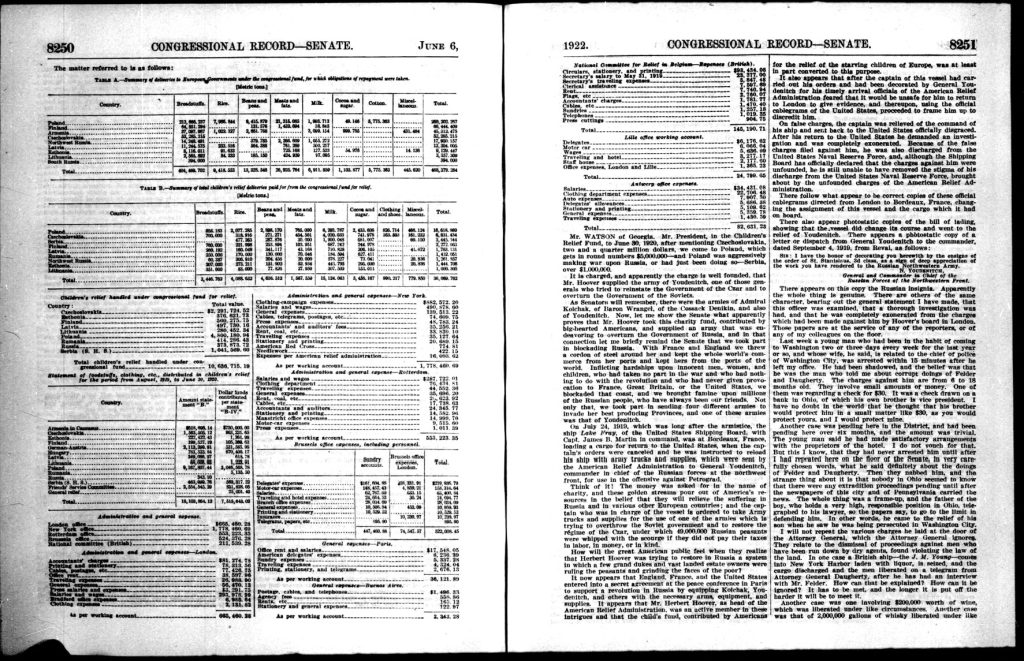

In June 1922, Harvard-educated aviator and plane manufacturer, Captain James Vernon Martin, testified before the US Senate on the misappropriation of relief funds by US Secretary of Commerce (and later President) Herbert Hoover. His claim was simple; in July 1919, as anti-Bolshevik forces made serious advances against the Red Army defending Petrograd, Martin received a message from Hoover in London to take the cargo of food intended for millions of famine victims and reload it with trucks and military supplies in support of an imminent attack on Lenin. Britain, France and America had thrown a ‘cordon of steel’ around Russia, preventing the natural flow of commerce around her ports, sabotaging railway communications and refusing essential trade; the famine her people were now enduring was, Martin claimed, one the allies had created. Worse still, the charity funds set-up by Hoover and the American Relief Administration to relieve this crisis, were being covertly looted to restore the regime of the Tsar — one of the most brutal and autocratic regimes known to modern history. This ‘Secret War Pact’, Martin alleged, had been hatched by an anti-Bolshevik league led by British War Secretary, Winston Churchill, during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. [1]

Any attempt to dismiss Martin’s claim as the resourceful vitriol of a failed inventor or a fantasist is likely to be frustrated by his impressive, and frankly quite extraordinary, C.V.

In 1900, the 17-year old Martin had self-published a pamphlet that not only earned the full support and approval of the National Democratic Committee but also featured contributions from US-Scottish Industrialist, Andrew Carnegie and Senator William Jennings Bryan. The pamphlet, ‘Our Flag Unstained: Imperialism, Tyranny and Oppression’ provided a 13,500 word challenge to the US annexation of the Philippines (1898) and its arguments found favour with the Anti-Imperialist League, of which Carnegie and Bryan were both members.

By 1909, Martin had enrolled as an under-graduate at Harvard University. Under the guidance of meteorologist Professor Abbott Lawrence Rotch, the feisty young inventor founded the Harvard Aeronautical Society with Rotch elected as President. With over 300 members and over 2000 feet of aerial film footage, the Society had been tasked with making theories of aeronautics more accessible across the colleges. Martin told the Boston Sunday Post that in a few years time, “we may expect to see all sorts of wonders … and there will soon be a transatlantic aeroplane”. That same year, Martin became a member of the Aerial Experiment Association led by Alexander Graham Bell, working closely with aviation pioneers, Glenn Curtiss and August Moore Herring. A ‘Harvard Aviation Meet’ in September 1911 marked his first contact with British plane manufacturers, Claude Grahame-White and Alliott Verdon Roe. [2] As a result of the meeting Martin assisted Claude Grahame-White during his subsequent tour of the Point Breeze Flying Club before training as a flying instructor at White’s aviation school in Hendon, England. By May 1911, Martin is taking part in a demonstration of military airmanship at Hendon before an audience that includes Secretary of War, Lord Haldane, members of the army council, 200 members of parliament as well as naval and military officers. He is joined by Grahame-White, Louis Bleriot, Alec Ogilvie, Gystave Hamel and AV Roe. [3]

Upon qualifying as a flying instructor, Martin was drafted in to teach at the Aerial Navigation Company owned by Charles J. Gliddens, an old partner of Graham Bell. Immediately prior to the war he found employment at Hendon Aerodrome where he trained several ‘of the greatest fliers of the Royal Flying Corps”. [4] A short time later in March 1917, Martin was presented with an award by retail magnate, Rodman Wanamaker and the Aero Club for his invention of the aero-dynamic stabilizer, an early and ingenious auto-pilot device.[5] In the mid-war period he served as First Officer of former France, Russian and Germany naval attaché, Rear Admiral, Aaron Ward (1851-1918) of the SS Red Cross, and it is during these aid voyages across Europe that Martin learns that America is alarmingly underprepared. [6]

The list goes on …

What Capt. James V. Martin was doing in Russia

After the declaration of the Armistice in November 1918, the Allied Powers backed a counter-revolution in Russia led by Tsarist (White Russian) forces. For the West it was something of a proxy war, direct military action, officially at least, was to be carried out exclusively by the Tsarist Loyalists and a multi-national alliance of foreign nations including Czechoslovakian, Estonian and Finnish militarists.

Between July and October 1919, with morale and provisions low amongst Bolshevik troops, the press were anticipating the imminent collapse of Russian Bolshevism. Food supplies were exhausted, and General Yudenich’s North Western Army, under pressure from the British, was making continued advances on Petrograd. Anti-Bolsheviks hoped it would be a defining moment for the counter revolution. Yudenich cabled an urgent request for aid to the London office of the American Relief Administration (A.R.A).[7]

On July 30th 1919, the Press Association reported that ‘a lack of food prevented (the) capture of Petrograd’. Yudenich described it as an ‘opportunity missed’. The advance from Pskov had been rapid but a lack of provisions meant they could not take Petrograd (at this time Leningrad). An American official tells the UK’s Manchester Guardian that allied forces could not occupy Petrograd unless they could guarantee the feeding of the city (the whole episode is addressed by Churchill and other MPs in the House of Commons. [8]

In August 1919, the Washington Post tells its readers that the delay in sending relief to ‘defenders of liberty in Russia’ will deal a serious blow to the counter revolutionaries. They conclude that this is ‘the duty of this hour’ and cannot be ‘relegated and delegated to a hypothetical League of Nations’. Such an active and direct response to the requests made by General Yudenich would be controversial. We were not officially at war with Russia and the provision of aid had been agreed on the basis that it was a strictly humanitarian mission assisting families and not regimes. Any military support offered should be defensive. The Washington Post dated 18 October 1919 reports that Yudenich was making further requests for food relief. As a result, another cable went out to the London offices of Hoover’s A.R.A.

In 1917, US President Woodrow Wilson made engineer and mining magnate, Herbert Hoover, director of the United States Food Administration (aka. ‘Food Tsar’). As the war ended, the US Food Administration was rebranded the American Relief Administration and registered as a non-profit organisation in July 1919. Directors alongside Hoover included Julius H. Barnes, R. W. Boyden, Edward M Flesh, William A. Glasgow, John W. Hallowell and Howard Heinz. Hoover was tasked not only with providing food relief across Central and Eastern Europe, he was also made responsible for the social and economic reconstruction of the region.

The Shipping Board, the United States Grain Corporation and the American Red Cross were all obliged to cooperate with Hoover’s ARA efforts. The US Congress would later hear that Red Cross supplies, under direction of Henry P. Davidson of J.P Morgan, were being used to feed White Russian armies. This whole project coincided with efforts by President Woodrow Wilson and British Secretary of War and Air, Winston Churchill, to defeat Bolshevism, plans were now meeting with considerable opposition on both sides of the Atlantic. There were few public figures who wanted to be seen attempting to restore a regime whose figurehead the Tsar, was reviled around the world for his institutionalized brutality and repressive state apparatus.

Churchill’s attempts to launch a ‘private war’ with the Bolsheviks was dealt a serious blow in the Spring of 1919 when the Daily Herald in London leaked a War Office memorandum marked ‘Secret and Urgent’, directing commanding officers to report on potential troop resistance to serving in Russia. The memorandum was dated January 1919, and arrived just as Britain and the US were considering large scale intervention on a more offensive tack. [9] That same month, the British War Cabinet had refused expanding the Expeditionary Forces and the Slavo-British Allied Legion (composed almost entirely of volunteers) and more creative efforts were clearly being pursued. Using the mechanisms put in place for Hoover’s European Relief effort formed that following month (February 1919) may have been one such option.

Wilson had already asked for, $100, 000, 000 in European relief. According to a 1921 Senate hearing led by John Reed of Missouri, Hoover admitted much of the aid was directed to the armies of Poland, Finland and Estonia for distribution — key players in the fight against Bolshevism. [10]

By the time the war had started Hoover had significant holdings in Russia and the Romanov family themselves were amongst his many partners. Walter W. Liggett, investigative author of the grudge-published The Rise of Herbert Hoover, contends that Hoover’s business interests had been thwarted by Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who had cancelled the concessions Hoover and Leslie Urquhart held through Irtysh, Tanalyk, Kyshtym and Russo-Asiatic Corporations. Irtysh, Tanalyk, Kyshtym were subsequently amalgamated into Russo-Asiatic Consolidated Ltd and in1912 were worth something in the region of one billion dollars. [11]

By the end of 1918, the British Foreign Office had recruited Urquhart to run the Siberian Supply Company. This forward-thinking trade instrument was a joint British-Canadian commercial agency for Asiatic Russia and the Kolchack regime in Siberia had a proposal in the pipeline to share generously in the profits. Having already had all his mines in the region nationalized by the Soviets, the move was something of a no-brainer. The British Department of Overseas Trade next offered Urquhart an advisory role in their supporting venture: the Russo-Canadian Development Corporation.

In the summer of 1919, the left-wing Daily Herald began to question the probity of such a deal: “some members of parliament might be worse employed than in eliciting information about the financial relationship between Siberian Supply Company, the British Government and the Kolchak junta. [12] According to the Paris edition of the New York Herald, a leak from an undisclosed source in Japan in April 1919 had made things abundantly clear: a group of British and American bankers had agreed to make a loan to Kolchak’s rival government in Omsk.[13] In return for the loan, and a handsome stake in the profits, Kolchak’s government would award mining concessions in Kamchatka to a syndicate that is likely to have included America’s Samuel McRoberts [14] and Frank A. Vanderlip — a key player in his friend Herbert Hoover’s 1920 bid for the Presidency and a major loser in the $26 million purchase of Russian Government war bonds and loans — all lost as a result of the October Revolution.[15] Similar concessions in Central Asia and Turkestan would likewise be awarded to Russo-Asiatic Consolidated Limited whose chairman was Leslie Urquhart. [16]

In return for the mining concessions, the Entente Powers (or the “Big Four” as they were known) would also need to recognise Kolchak’s White Russian Government in Omsk as the de facto government of non-Bolshevik Russia.[17]

The Daily Worker reports on Martin’s testimony at a Federal investigation into Harry M. Daugherty and the ‘Ohio Gang’ in April 1924, a bribery and corruption scandal featuring oil.

Reilly and farroway sail in

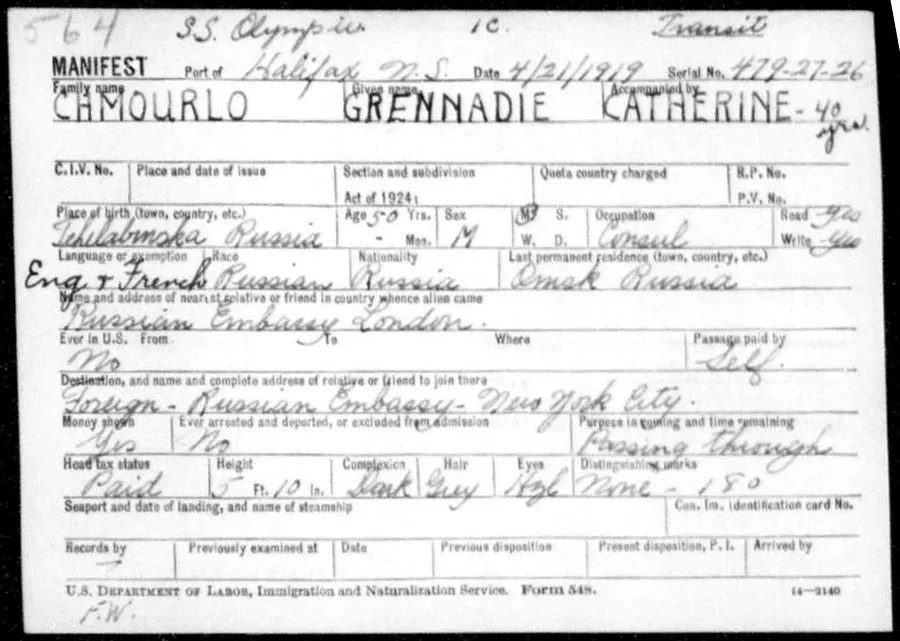

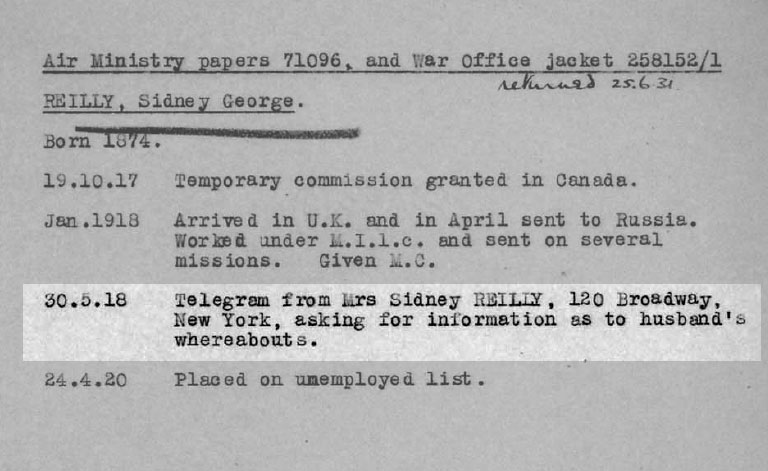

News of the provisional agreement with Kolchak’s White Russian Government in Omsk coincided with two things: the arrival of a telegram at the Reuters News Agency describing the discovery of gold-bearing reefs near the source of the River Angara, some 900 miles from Omsk, and the arrival in New York City of a small delegation from Whitehall in London featuring super-spy, Sidney Reilly, Grennadie Chmourlo — a representative from Omsk attached to the Russian Embassy in London — and Reilly’s deeply mysterious business associate, Anthony Jechalski, who operated under a variety of aliases. [18]

As polo-playing nobleman’ Tony Farroway’, Jechalski had already been accused with bribery and corruption. His accomplice in these particular activities was Colonel Vladimir Nekrasov of the Russian Supply Committee in New York.[19] In a previous role, Reilly had acted as chief commission agent for the Russo-Asiatic Bank in the purchase of Japanese munitions for Russia’s Imperial Army.

The SS Olympic had arrived in New York in the last week of April and Reilly, in all likelihood, made straight for his old office at 120 Broadway, located in the same Equitable Building of Lower Manhattan as the Russo-Asiatic Bank and the recently restructured munitions wing of the Russian Supply Committee. The American International Corporation — a proto-type relief organisation set-up by Frank A. Vanderlip in 1915 — could also be found at this address. Chmourlo, by contrast was scheduled to meet his colleagues at the Consulate-General of Russia in New York City.

Accompanying Reilly on the SS Olympic were two other men: Captain Hamilton Halsey Herbert Noyes and Methodist missionary, Ernest W. Bysshe whose Episcopal Church was to play a key role in supporting Hoover and Vanderlip’s relief and reconstruction mission in Russia. Bysshe’s partner in these efforts was George A. Simons in Petrograd who was there on behalf of the Church’s Department of War Emergency & Reconstruction programme. [20] The treasurer of the Episcopal Church in New York just happened to be Reilly’s friend, Colonel Samuel McRoberts — the Vice President of the National City Bank who had been keenest to start the Anglo-American syndicate and gain an advantage over his rivals at J.P. Morgan. [21]

We should perhaps be clear about one thing; humanitarianism was not being used as some bait and switch stunt for Churchill and President Wilson’s purely military objectives, it was a key part of the matrix that would undermine the need for Bolshevism. That doesn’t mean the mechanisms used for aid couldn’t be commandeered at a critical time for arms, as Captain James V. Martin of the United States Shipping Board would learn that September.

By the time of Reilly’s arrival in April 1919, Samuel McRoberts still held considerable influence with supply contracts for the US Army. After being made Head of the Procurement Division in the recently reorganized Bureau of Ordnance in January 1918, everything the US used in the hurly burly of war had, until January 1919 at least, required McRoberts’ personal signature. “Billions flow when he signs his name”, screamed the headlines. McRoberts had also been prominent in railroad matters and interestingly enough, it had been Urquhart’s contention that railroads, and not food, were the single greatest challenge to the reconstruction of Siberia and its borders.

Just days after Reilly returned to London, the New York Times ran an appeal for Reverend Bysshe’s Episcopal Church immediately beneath a report of a speech made by President Harding at the Carnegie Hall the previous evening. The occasion of Harding’s speech was the American Day Meeting, held under the direction of the American Defense Society. The event had been arranged primarily as a protest at the anticipated spread of Bolshevism throughout Europe and America. [22] The appeal, which ran at a full half-page, was targeted at investors; there could be no lasting peace without understanding, there could be no understanding without education, and there could be no education without a $105,000 cash investment. Another advertisement on the page was for the New York Trust Company whose incoming trustee was Grayson M.P. Murphy.

Murphy, who had poured $125,000 of his own cash into setting up the anti-Communist American Legion, had resigned his Presidency of the Guaranty Trust Company in January 1919 just as the company was finding itself at the centre of an investigation into the illegal sale of munitions to Mexican Revolutionary, Pancho Villa. The sale was alleged to have been organised by German agents, Felix Armand Sommerfeld and James Manoil. The pair had been charged with channelling funds through Guaranty Trust and the Mississippi Valley Trust Company located in James V. Martin’s hometown of St Louis.[23]

The Trustee of the Mississippi Valley Trust into which such vast sums of cash were placed by Sommerfeld and Manoil was David Rowland Francis, appointed Ambassador to Russia by Woodrow Wilson in March 1916. In 1904 he had been President of St Louis’s World Fair, whose celebrated ‘Airship Contest’ provided the 21 year-old James V. Martin with his first competitive platform. It was here that James found himself working alongside his future Harvard mentor, Professor Lawrence Rotch.

A street address that became central to the Guaranty investigation was 165 Broadway, New York. It was here that the Romanian and suspected German agent James Manoil had registered the head office of his Manophone Company. Another man with connections to 165 Broadway was British super-spy, Sidney Reilly. [24] According to documents held by the Bureau of Investigation, Reilly had visited 165 Broadway during 1917 and 1918 when he called on Colonel Frederick W. Abbot and Russian Munitions Chief, Vladimir V. Oranovsky to discuss Anglo-Russian contracts with longstanding rifle manufacturers, Remington Arms. [25] Colonel Oranovsky had arrived in New York in June 1917 just as Kerensky’s provisional government began to make good on the trading opportunities discussed by former American Secretary of State Elihu Root and Minister-Chairman Kerensky in Petrograd that summer. His colleagues at the Russia Supply Committee in New York included Professor Yury Lomonosov (Ministry of Railways) and Professor Nikolai Borodin (Ministry of Agriculture).

Between 1915 and 1917 Russia and Britain had placed some of their largest contracts with the Remmington Cartridge Company and millions of dollars were owed. When the Revolution of February 1917 took place, any existing contracts were thrown into disarray. The British Treasury issued a swift announcement that they would be backing up the Russian Government in making payment for war munitions bought in the US by Russia. The New York Times reported on February 25, 1917, that “the joint financial arrangement, in the opinion of bankers, is expected to expedite the shipment of goods to Russia this spring”. The Bethlehem Steel Company, on whose board Grayson M.P. Murphy had served as director, pledged British Treasury notes totalling $37,600,000 in value as collateral behind a $50,000,000 contract. [26]

A bigger blow to the contract was dealt by the second Revolution in October. Lenin and the incoming Bolshevik Government effectively wrote-off all debts owed to the US arms manufacturer and production was only resumed after an agreement was quickly drafted between the Imperial Russian Embassy and the United States government. To secure the arrangement, the British Mission’s Colonel Abbott and the Duma’s supply adviser, R. V. Poliakoff acted as trustees of the Russian Remington Rifle Contract, registered to Reilly’s 120 Broadway address. A mechanical engineer by profession, Poliakoff represented Russia’s relief organisation, The All-Russian Zemstvo Union, a key distribution partner for Grayson M.P Murphy’s American Red Cross and YMCA.

Advertisement taken out in the New York Times by the Russian Information Bureau shortly after British Spy Reilly arrives in New York

The Russian Supply Committee — Corruption in Confusion

The Committee and its successor, the Division of Supplies of the Russian Embassy, coordinated and supervised the purchase of military supplies for the duration of the war. It had a large staff of officials, several of whom were detailed from Russia and the government of the Tsar. The majority however, were agents and intermediaries whose exact rank and status for the most part remains unknown. And with such a colourful melange of individuals passing through its doors, the Committee was inevitably plagued by repeated episodes of corruption and ‘cloak and dagger’ escapades. [27]

By the end of 1914, over £60 million had been loaned by the Brits to Russia. The failure of the Russian State Duma to centralize procurement now meant an unruly collective of businessmen in New York were immersed in a shady cycle of bribery and kickbacks. A lack of qualified munitions inspectors only added to the general incompetence. Most of these men were lawyers by education, thrill-seekers by inclination and Officers by the necessity of war.

The February Revolution of 1917 only added to the chaos. In March 1917 the New York Times was reporting that there were now two munitions commissions competing for the right to represent the Russian State Duma Government in the US. Despite being a welfare organisation, Poliakoff’s party of liberal progressives – the Zemstvos Union – was quick to denounce the retention of consuls and advisers representing the old regime, and declared their intention to take sole control of munitions purchases. With the Tsar’s advisers out of the way, the Russian Duma could pursue victory over Germany with what Poliakoff would describe as a “new energy”. [28] In this they were supported by the ever-changing coterie of rivalrous industrialists that made up Alexander Guchkov’s War Industry Committee and the Cities Union at New York’s Flatiron Building. That they had the support and confidence of Robert Lockhart Bruce, another British Agent, may have been why his friend, the ‘master spy’ Sidney Reilly, was able to position himself so centrally within this organised pandemonium. In Lockhart’s words, the Zemstvos and the Cities Unions “were the nearest Russian equivalent to our Ministry of Munitions” and channels were well and truly open. [29]

That same April, Kolchak had addressed a joint session of the Municipal Council and the Zemstvo Assembly. For many years the Assembly had been a two-tier organisation composed of land owners and peasant councils providing welfare support and modicum of self-governance for local villages, a not entirely convincing stab at wrestling some form of constitutional control from the Tsar. Kolchak’s proposal was to offer total overhaul of the land and labour policies and ensure a much greater share in the profits for workers. In return the Zemstvo unions would support Kolchak’s efforts to destroy the Bolsheviks. In February 1919, the Socialist Groups in Omsk had made a separate declaration of support, and similar pledges were to be made by the Socialist Revolutionaries, Social Democrats and Labour Unions in Perm in May. At least that’s how the Russian Information Bureau in New York was spinning it.

In June 1919, the New York Times ran a full-page advertisement for Arkady Joseph Sack’s ‘Struggling Russia’ journal, whose publishers, the Russian Information Bureau, were located at the nearby Woolworth Building (233 Broadway). The ad’s headline announced that it was “The Duty of The Allied Democracies to Recognize the Omsk Government”. Kolchak’s ‘All Russian Government’, with the support and co-operation of the Zemstvos and Cities Unions, pledged itself to convening an All-Russian National Assembly “as soon as the plague of Bolshevism” was destroyed.[30] The journal’s team of advisers just happened to include railroad magnate Jacob Schiff – the director of the National City Bank who’d helped finance the Japanese defences against Tsarist Russia – Charles H. Sabin of the Guaranty Trust Company and Samuel McRoberts, Reilly’s new best friend in New York. [31] The article had been written back in May, just as Reilly was returning to London.

Curiously, in October 1919, just as the investigation into the Guaranty Trust-James Manoil arms deal got underway, Kerensky’s long-serving munitions chief, Colonel Oranovsky had died as the result of an accident on the Brooklyn subway. Oranovsky’s recovery was sufficient enough that he was allowed to leave hospital. But just three weeks later the former chief of the Tsar’s Military Cabinet was found dead at his home in Long Beach. [32]

Murphy’s Guaranty Trust gained further notoriety when it was discovered that the company had withheld over $5 million deposited in its bank by the Provisional Kerensky Government in Russia in July 1917. Unsurprisingly, the incoming Soviet Government put in a subsequent request for the Guaranty Trust to become their US fiscal agents “for all Soviet operations and contemplates”. [33] Grayson Murphy, who had served as European Commissioner of the American Red Cross during the War, was later implicated in a plot to overthrow President Roosevelt with members of the American Legion (which is something I’ll come back to later).

As Guaranty Trust’s former trustee, Grayson M.P. Murphy pursued other financial opportunities with the New York City Trust, Colonel William J. Donovan, a friend of Murphy’s from his days in the Intelligence wing of the so-called ‘Rainbow Division’, was making his way to Omsk on a special mission for President Wilson. Donovan had already undertaken duties for Hoover and Murphy on the Europe Relief Effort. This time he was working exclusively for Wilson on an objective report that would determine the future of US intervention in the Russian Civil War. In July 1919, as Martin’s USS Lake Frey left for Reval from France, Donovan arrived in Omsk with Major General William Graves to meet Kolchak. His brief was to assess the credibility of the General’s forces against the Bolsheviks. According to Donovan’s biographer, Richard Dunlop, the taproot of America’s Office of Strategic Services and CIA reached back to this moment.[34]

Appeal made on behalf of E.W. Bysshe and Samuel McRoberts’s Methodist Episcopal Church below report of anti-Bolshevik rally, May 1919

‘Ace of Spies’ in New York Urgent Government Service

Another of Sidney G. Reilly’s travel companions in April 1919 was Captain Hamilton Halsey Herbert Noyes, a British army officer who had previously led a commission of British mining interests in Natal, Cape Colony. In the years leading up to the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905, Noyes had been placed in charge of inspecting the naval defences at Port Arthur. [35] Reilly was also based here at this time as a partner in a firm of timber merchants, secretly monitoring and recording the Japanese and Russian schedules around the base. Noye’s knowledge of Japanese movements around the port would, like Reilly’s, be invaluable in assessing their intentions in Siberia and the viability of securing a US naval base at Kamchatka. The Japanese had over 100,000 troops in Siberia and the scope for intrigue was enormous. The notes on the manifest for the SS Olympic indicate that Noyes was on his way to see family in Chicago, but this seems doubtful given his skills and knowledge base. His occupation was also listed as ‘British Government Official’, a further indication of his actual business there, and the fairly routine effort that may have been put in place to conceal it.

According to a secret memorandum obtained from the War Office dated April 17th 1919, Reilly was travelling to New York on “urgent Government service”. [36] On a previous occasion, Desmond Morton [37], Churchill’s personal man of choice in Section V of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service — the counter-Bolshevism Department — had denied any knowledge of Reilly’s April trip to New York, relating that Colonel Menzies was of the opinion the trip was a ‘private one’ and that the sooner that Reilly got back in touch with HQ, the better for everyone involved. [38] From what we know now, that wasn’t true. Churchill, still serving as British Secretary of State for War and Air, had placed an inordinate amount of stock in Reilly’s nineteen-page memorandum, ‘The Russian Problem’. Reilly was the man of the moment. Churchill and Morton believed his five point review of the situation on the ground in North Russia held the key to dismantling the Bolshevik threat.

Just prior to his April trip to New York, Reilly had met with Churchill, his aide Sir Archibald Sinclair, Wilson adviser, William Bullitt Jr, [39] and a party of Admiralty officials at the Hotel Majestic in Paris during the first phase of the Paris Peace Conference. [40]According to fellow spy, Robin Bruce Lockhart, it was at the Hotel Majestic in February 1919 that Reilly introduced Churchill to his friend, Boris Savinkov, a Socialist Revolutionary who had served as Assistant War Minister in Kerensky’s Provisional Government. He was also Kolchak’s personal envoy in Paris. [41]

Churchill’s aide, Archibald Sinclair, was even more ebullient when Reilly delivered a follow-up review in June 1920. In his opinion Reilly was “without a rival” among his Russian and Anglo-Russian visitors. [42] On the strength of his services to date, Churchill had Morton put in a request for Reilly’s promotion from Lieutenant to Major. The request was duly denied. Reilly had so far enjoyed a temporary commission as Second Lieutenant. War Office bureaucracy forbade such a move; it was simply out of the question. [43]

Around this same time, James V. Martin, the man who would eventually blow the whistle on the Churchill-Hoover plot to ship munitions to General Yudenich was steaming across the North Atlantic from Montreal to Hamburg with over 3,000 tons of grain for distribution in Czechoslovakia. After being enlisted into the US Naval Reserve from Elyria, Ohio in the last month of 1918, Captain Martin of the Relief Delivery Vessel, the USS Lake Frey, was back in his pre-war role as Master Mariner. His secondment to Hoover’s American Relief Administration lasted from May 8th 1918 until January 7th 1920. The previous summer had seen Martin shuttling between France and England, overseeing the demonstration of the state-of-the-art Martin Scout K-III built for the British Air Board on behalf of his employers, the U.S Air Service under Colonel Thomas Milling. In Paris he would join Colonel Bolling at Billy Mitchell’s training school. Back in England Martin would meet Alfred Baldwin Raper, scout for special missions in Britain’s Royal Flying Corps and a personal friend of Sidney Reilly.

Martin’s trip to Estonia the following month on behalf of the American Red Cross would prove far more controversial.

Ship manifest dated 19th April 1919 showing Sidney Reilly travelling with Omsk Representative Grennadie Chmourlo and Anthony Jechalski to New York

A debate led by Communist MP, Cecil John L’Estrange Malone in the British House of Commons the following year, was to identify and challenge some of the issues that made the Omsk pact agreed in April so very problematic: Russo-Asiatic Consolidated Limited was an amalgamation of businesses formerly controlled by Leslie Urquhart (including Kyshtim and Irtysh). Canadian-British Stockbroker Edward Mackay Edgar was down as controlling influence and the extent of British and French investments in Russia was estimated to be around the £1,600,000,000 mark. Malone went on to describe how the British Trading Corporation was the outcome of the Farringdon Committee who were anxious not to see Bolshevism spreading to Hungary. The BTC had one of two branches in Hungary, the other being at Danzig, where Martin’s SS Loch Frey had been docked.

In his next move, Malone levelled a more pointed challenge to the First Lord of the Admiralty, Walter Long who had £500,000 of debenture stock in Anglo-Russian Trust Ltd. Malone’s gripe with Long was that as First Lord of the Admiralty, Long had played a central role in imposing the blockades on Russian ports that had resulted in the food shortages in the first place. [44]

Incidentally, Frank A. Vanderlip, who had co-organised the syndicate in receipt of concessions from Kolchak had only just resigned his post as President of the National City Bank and it was Vanderlip’s rush-published book, ‘What Happened to Europe’ that set-out to provide the right ethical and economic context for American intervention in the Russian Civil War and Hoover’s American Relief Administration. The book contended that Europe was now so close to social, political, and economic collapse, that it demanded the immediate organization of a huge international consortium of governments and bankers to coordinate and finance all European relief and reconstruction projects. [45] Was Russia to be included in those reconstruction efforts? Not until the contagion of Bolshevism had been defeated. Attempts to grant credit facilities for the rehabilitation of Europe could not include Russia, as Russia was “for the time being” outside the pale of capitalist consideration. There was, he wrote, “no government with which capital can contract”. In Vanderlip’s view, Bolshevist Russia must, for the present, be economically isolated. The book’s ‘Power of Minorities’ chapter was unequivocal: Bolshevism would spread in countries where industry was paralysed and idleness was accompanied by “want and hunger”. Fourteen countries bordered Russia and each of them were exposed to the contagion. [46]

In separate addresses, Vanderlip urged American recognition of the anti-Bolshevik Russian forces of General Alexander Kolchak, the leader of the continuing White Russian counter-revolutionary effort, as the legitimate government of Russia. Vanderlip’s National City Bank had opened its first Russian branch in Petrograd just weeks before the First Revolution in Russia, after underwriting a series of bonds in support of the Tsar’s regime. The bank opened on January 15th 1917, having negotiated an agreement with the Russo-Asiatic Bank and International Bank of Petrograd by which it would guarantee the finance of payments in New York for American goods purchased by importing firms in Russia. Analysts were also quick to notice that in the weeks and months prior to the revolution no fewer than nine of the leading banks had increased their capital and that there was movement in favour of the creation of “purely industrial banks” like those involved in mining. [47] Vanderlip’s book was completed in April 1919, just as America was receiving ‘private advises’ from Kolchak’s Osmk emissary, Grennadie Chmourlo and British spy, Sidney Reilly, on plans to go ahead with the deal.

In July 1921, Leslie Urquhart, whose Siberian Supply Company had been entrusted by the British Foreign Office with supporting the White Russian Kolchak Government in Omsk, was sensationally appointed President of the Association of British Creditors of Russia (ABC of Russia). This time he was tasked with securing trade and his efforts with the now-dead Kolchak’s bitterest political rival, Lenin. An somehow, against all expectations, Urquhart’s efforts to work in tandem with the ‘Bolshie’ and belligerent Hands Off Russia campaign, looked set to pay off handsomely.

In May 1922, just two weeks before Captain Martin’s claims about the misappropriation of funds were brought before Senate, Hoover and Urquhart’s Russo-Asiatic opened new negotiations, this time with Lenin’s Soviet. The move couldn’t have been more controversial, especially among the company’s previous allies at the Equitable Building in New York. Faith in the White Russian movement had collapsed. Intelligence officer, William J. Donovan had returned to Washington with his report for President Wilson; the anti-American attitude on the ground in Siberia was substantial and on December 31st 1919 an order was received by the US Expeditionary Forces to withdraw. Kolchak had been defeated and his death in February 1920 signalled a change in direction for Hoover and the Presidency. Despite all their obvious concerns, trade with Lenin’s Soviet was now inevitable.

Between August and September 1922, Urquhart had started talks with Leonid Krassin and made several visits to Moscow and Riga. The trips resulted in the signing of the so-called Urquhart-Krassin Agreement (also known as the ‘Urquhart Concession’), which drafted the outline of a $56, 000, 000 oil deal (never ratified). The press duly reported that the agreement would see the Soviet return the 2, 500, 000 acres of land the company had reserved in Siberia and receive $50,000 in compensation.

Although Hoover had been obliged to resign his formal connection to these companies as he took his first slippery steps on the road to public life in 1914, I think it would be naïve to view it as a complete withdrawal of his financial stakes. By the summer of 1914 Hoover’s mining interests in Russia were on the threshold of major success, but Hoover throughout his political career was careful not to court charges of a conflict of interests. Donald Trump resigned directorships ahead of his candidacy for much the same reason. Bill Clinton too. In 1914, having already been acting as emissary for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, Hoover was put in charge of coordinating the European Relief Effort and was fast becoming the world’s first shuttle diplomat. An appearance of neutrality would be critical to the success of the project and for the US to adopt the line, albeit briefly, as peace brokers. With the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, plans were also afoot for Hoover’s Relief Commission to negotiate relief with the Germans to feed Poland and Russia. When the deal with the Soviet was announced, Hoover issued a statement to the press indicating that he had not held interests in the company since 1916. [48] He did however, make one concession: American trusts did have a significant volume of cash to recover from any trade pact with Russia. His defence was that the amount was greatly shadowed by the money they had spent on aid. People, he said, had convinced themselves the trusts who were anxious to recover their pre-revolution investments were dominating American government. [49] However, the question is not whether Hoover retained these interests covertly, but whether Senator Thomas E. Watson, who was among the first to hint at interests, was convinced he still had holdings. Hoover’s decision to remove his name from Russo-Asiatic was probably an indication of just how central Russia would become to his bid for office and President Warren G. Harding’s post-War US economy in general. He was a dutiful Democrat under the Wilson administration, but a more capable Republican under Harding.

Reports in the press in December 1916 reveal the outlook for Russo-Asiatic to be really very promising indeed. Significant funds had been raised and the anticipated revenues coming were expected to be considerable. [50] After providing their initial, support Hoover and the American State Department were quick to appreciate that the blockade around Russia would gravely hamper the transition from war economy to peace economy. Hoover pointed out that the blockade being pushed by Britain was strangling the Central Powers and causing ‘distress among the neutrals’. [51]

It would be nothing short of foolish to presume that a man of Hoover’s commercial magnitude had lost faith in the Russian project and just bailed out. Investments aren’t without their challenges and some long-term stability would need to be maintained in Russia for shares to hold. To maximise profits however, Russia would need to change. And change was more likely to happen if the right context and consensus could be built from within. The opening gambit of attempting to restore order by recalibrating an old regime had failed. The chaos and instability had only been extended by civil war.

By 1922, President Wilson and Herbert Hoover had begun to look further ahead. With peace came stability, and with stability came trade. Economic barriers could be removed (Wilson set forth his conditions for Russia in Point 6 of his Fourteen Points declaration). Food was about to be weaponized. Disaster capitalism was about to be born.

Capt. James V. Martin’s claims examined at a Senate Hearing

(67th Congressional Record-Senate June 1922)

James V. Martin and the Relief Wars

It was during the period in which Hoover, now serving as US Secretary of Commerce, and Leslie Urquhart were continuing trade discussions in Russia that Senator Thomas Watson of Georgia made the astonishing claim that Hoover had misappropriated funds belonging to the American Relief Administration — donated by “big hearted Americans” on a strictly humanitarian basis — to finance the final and unsuccessful military advance on Petrograd. According to the press, Hoover’s aide, Captain T.C. Gregory, had already been boasting that the maladministration of Hoover’s war time relief mission had helped overthrow the Hungarian Soviet Republic and that a similar campaign had been carried out in Poland as its armies made advances on Poland. In January that year further claims had followed. Captain Paxton Hibben, who had assisted the ARA with his work with the Russian Red Cross in 1921, had said in a public meeting in New York that the ARA had been failing in their duty to feed the starving. The feeling among some was that Hoover and the ARA had been deliberately sabotaging the Russian Relief program from within. [52]

A month earlier Watson had made the astonishing claim that Hoover had been withdrawing $10,000 dollars a month from the funds for his own personal use. [53] The man that Watson called in as witness on June 15th was James Vee Martin, who had his own explosive story to tell. Over the course of several years, many of these charges would extend to US Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty (charged with bribery and corruption) and other members of the so-called ‘Ohio Gang’, a gang of politicians supporting President Warren G. Harding.

Captain Hazel. L Scaife, an investigator for the Justice Department had been brought in as a witness against Harry M. Daugherty. In April 1924, it was being reported that Scaife had uncovered evidence that the Wright-Martin Aircraft Corporation had overcharged the US government $2,267,342 on war contracts while failing to deliver a single fighting plane to France. [54] His resignation from Justice Department was duly handed in; Scaife’s charge was that President Harding and Harry M. Daugherty were stonewalling the investigation. In another move, Scaife backed Senator Watson’s claim that Hoover and the ARA spent over $100,000,000 on aiding counter revolutionary forces in post-War Russia. Hoover’s old friend, Frank A. Vanderlip, the man whose bank would have benefited handsomely from the deal being offered by Kolchak in the event of a White Russian win, also volunteered to testify in the corruption hearings relating to Harding.

This wasn’t the only challenge Hoover would face that year. In late 1921, an investigative journalist from Chicago, Walter W. Liggett would look to Herbert Hoover to endorse and support a rival famine agency being organized to help alleviate the emerging Povolzhye crisis. But no such support was forthcoming. In Hoover’s opinion, Liggett’s American Committee for Russian Famine Relief was much too close politically to the pro-Bolshevik fringe of Dr D. H. Dubrowski and the Soviet Red Cross. By February 1922, a series of reports had begun to circulate among reporters that funds raised by Liggett and Dubrowski were being covertly re-distributed amongst pro-Soviet causes. A recommendation was put in to President Harding that US famine relief efforts be controlled exclusively by President Hoover, whose American Relief Administration was now muscling in on fresh aid efforts in Russia. Defending himself against the surly innuendo of the conservative press, Liggett quoted the rumours of the misplaced funds raised originally by James V. Martin. A telegram sent by Liggett to Hoover read: “the investigation … should establish the truth concerning charges that the Poles were helped when invading Russia by relief organisations directed by Mr Hoover, as well as possible connections … with foreign corporations which may have had extensive valuable commercial concessions from Russia.” [55] Perhaps sensing that the political and logistical details might be lost on most Americans, Watson did his best to explain the charges in the most sentimental and simplest of terms. Addressing the Senate in June 1922, the former Populist politician drew on all the tricks and devices he had built up as an attorney:

“Think of it! The money was asked for in the name of charity, and these golden streams pour out of America’s resources in the belief that they will relieve the suffering in Russia and in various other European countries; and the captain who was in charge of the vessel is ordered to take Army trucks and supplies for the use of one of the armies which is trying to overthrow the Soviet Government, and to restore the regime of the Tsar, under which 49, 000, 000 Russian peasants were whipped with the scourge if they did not pay their taxes in labour, in money, or in kind.”[56]

The ‘Relief Wars’ had begun in earnest.

In spring 1924, James Vernon Martin, still married to aviatress Lily Irvine, was brought in as a witness by Scaife. [57] Although the congressional records suggest that Congress heard of these allegations as early as June 6th 1922, this was the first time the press were to report on Martin’s testimony.

Captain Martin alleged that on July 24th 1919 he was in command of the 4,000 ton US Shipping Board vessel, USS Lake Frey, docked in Bordeaux, France and loaded with relief supplies for a return trip to the US. He claims that he was cabled a message from the London office of Hoover’s A.R.A with instructions to reload the cargo with 60 Q.M.C Class Liberty trucks, 150 drums of oil and supplies and deliver them to General N.N. Ivanoff, the Central Agent of Supply for the Russian North Western Army under General Yudenich in Reval. It was Martin’s belief that there was a secret understanding between Churchill, Hoover and the French Government (which he refers to as ‘the Paris Bureau’) for the British to provide additional planes, tanks, and oil to the counter revolutionary movement that was never fulfilled by Churchill. Martin alleges that the British fleet waited in Reval to ‘steam up to Petrograd’ in the event that the equipment arrived. The British Labour Party’s threat to strike unless British troops were immediately withdrawn from North West Russia had, in Martin’s opinion, dealt a devastating blow to Yudenich’s advance on Petrograd. There had been such a noisy outcry from the Labour Party that Churchill had found himself unable to move the British Fleet from Reval toward Petrograd. The 160, 000 Finnish troops waiting would not advance until the British fleet arrived. The German forces of Goltz and Bermondt were contracted to help but quickly found themselves embroiled in a private war in Latvia, leaving the rear of the advance exposed. A telegram from British Military Attaché, Frank Marsh to the British War Office dated August the 10th was of the opinion that any attempt to take Petrograd ‘without German Influence becoming paramount ‘was practically ‘impossible’. [58] As a result of Churchill’s failure to send the equipment, Captain Martin was asked by Brigadier Marsh of the British Army to purchase planes and heavy artillery from the Germans to help fulfil the policy of the American Government support for Yudenich. Certainly requests were being made to open up the German frontier for the passage of munitions at this stage. In a telegram from Colonel Tallents in Riga to Lord Curzon dated September 6th it was being asked if General Bermondt’s Western Army could purchase equipment from Germany and whether additional supplies and capital could be sourced from other ‘German Financial circles’. The request was repeated for General Gough.[59]

As Martin arrived in Reval, Alfred Baldwin Raper, a fellow graduate of the Grahame-White Pilot School at Hendon, was making further requests in Parliament that the British War Cabinet consider aerial support for Yudenich. He had put previous request before Churchill in April.[60] Ex-Royal Flying Corps pilot Baldwin Raper had been elected Conservative MP for Islington East in the 1918 elections, and had been decorated, like his old friend Martin, with the Russian Order of Saint Stanislaus. Kolchak’s Imperial Government in Omsk had awarded Raper the medal for testing planes and training pilots for the Russian Aviation Mission. Martin’s Florida-based flying associate, Tony Jannus, had assisted the Russian Mission in much the same fashion prior to the Revolution, after being dispatched with a consignment of planes for the Tsar’s Imperial Guard. During his secondment to the Foreign Office in late 1917, Raper himself had flown special missions in the Baltic before being redeployed to Murmansk in March 1918 to assist Captain Ernest Shackleton as part of the North Russian Expeditionary Force.

One thing that most people won’t know about Raper is that he also just happened to be one of super-spy Sidney Reilly’s key contacts in the Anglo-Russian Oil (Royal Dutch Shell) and aviation industries. In August 1919, Raper’s hope was that the British Government would grant permission to allow ex-Royal Flying Corps officers and mechanics to volunteer for active duty with General Yudenich. His wish was that the Cabinet supply General Yudenich with the planes, facilities and all equipment necessary. He argued that this was the best means of assisting Finland and strengthening her position as ‘the bulwark of Western Europe against the poisonous flowing flood of Bolshevism’. [61]

According to Reilly biographer, Richard B. Spence, Reilly ‘praised Raper as a loyal friend and anti-Bolshevik and an indispensable link to likeminded men in Parliament’. [62] Raper also shared James V. Martin’s belief that the progress of the aviation industry was being greatly retarded by corrupt and fraudulent practices in the British Treasury. An Air Ministry scandal that threatened to overwhelm the British War Office in August 1919 provided the ideal platform for Raper to propose the creation of a specially selected Committee “entrusted with the necessary powers, composed of a handful of MPs and gentlemen outside the house with business experience to advise the Air Ministry on financial and business affairs”. [63] That Raper’s international timber company lost a considerable share of its market after the Soviet-takeover may just offer a clue about his motives. There is another mystery to contend with: Raper’s second wife, Renée Angèle Rosalie Benoist was the daughter of Hector Benoist of Lille in France. The father of Thomas W. Benoist, the St Louis plane manufacturer and close associate of James V. Martin, had likewise been born in France. Did the deeply committed pilot Alfred Baldwin Raper end-up marrying into an aviation dynasty? Sadly, without knowing if Thomas and Hector Benoist are related, it’s really rather difficult to tell.

At the precise moment that Raper was making his speech in Parliament, Captain James V. Martin was steaming across the Baltic with his cargo of trucks and supplies to Yudenich in Reval, where he would wait for a consignment of planes and tanks that would never arrive.

On August 10th 1919 a new Government for North West Russia had been formed on Gough’s recommendation in Reval. The details were left to Marsh, who issued Yudenich with an ultimatum: unless a new government could be formed that backed the demands of the Estonians, British aid would be stopped. When the British Cabinet learned of Gough’s decision, he was recalled immediately to London. The Churchill-Hoover compact, and the associated mining concessions promised to the US-UK syndicate had been agreed upon the basis, and kept upon the basis, that the Kolchak Regime in Omsk would be recognised as Russia’s official anti-Bolshevik government.

On landing successfully in Reval well ahead of schedule in September 1919, Martin claims that he was decorated by Yudenich and presented evidence to this effect at US Senate hearing some three years later. The evidence consisted of an Order of St Stanislaus medal, 3rd Class, an accompanying letter, dated September 4th 1919 as well as the landing bill receipt which listed the full contents of the Captain’s hold. Martin also provided Congress with copies of the official cables sent by Hoover’s aide de camp, Major Newman Smith, from London to Bordeaux, France, changing the assignment of this vessel and the cargo which it had on board. [64]

Shipping logs for the American Relief Administration show that Martin’s ship, the USS Lake Frey arrives in Danzig, Germany on August 1st 1919 and was scheduled to land in Reval in October that same year with over 350 tons of food aid ($111,927,500 in total). In interviews with The Federated Press, Martin additionally alleges that the $4,450,000 worth of food was sold by the US to the ‘Provisional Russian Government’ in Paris, which he refers to informally as ‘The Paris Trust’, a committee of former Imperial Ambassadors that appears to have included representatives of General Johan Laidoner’s Estonian Army, General Yudenich’s White Russian Army, and Colonel de Wahl’s unit of the Baltic-German Land Defence forces.

During his mission, Martin, by his own admission, says he had been forced to commit two serious offences. The first was to have consented to a request from Herbert Hoover and E.C Tobey of the A.R.A in London to ferry Imperial Russian General Major ‘Ernest von Wahl’ from Paris to Reval. Worrying that this was a violation of shipping board law, Martin says that he sought formal assurance from his superiors before accepting the passenger. Martin showed Senate and the Press a signed letter from Wahl acknowledging that he was accepting special passage.[65] Martin’s second offence was to have purchased planes and heavy artillery from Germany.

After explaining the nature of the rules he had breached, Martin went on to describe how the A.R.A thought it unwise to let him return to London where he might provide evidence to the US Shipping Board. Hoover’s response was to relieve Martin of his command of the ship. He says Hoover did this by setting him up on false charges and publically disgracing him for negotiating private sales of ‘German war material’ to General Yudenich in Reval. Martin claims this was carried with the knowledge and support of Churchill and Hoover’s men in London. On arrival back in the USA Martin demanded a full investigation and the US Shipping Board cleared him of all charges. Sadly for Martin, that didn’t prevent his discharge from the United States Naval Reserve. [66]

Hoover did his best to deny the charges. Whilst admitting that food and trucks DID go to Yudenich he claimed they were used solely for the purpose of the civilian population and not to assist the military expedition. It was also acknowledged that the 60 trucks had been sold by the American War Department to the Russians in Paris. Hoover says he stipulated that the delivery of the trucks was on the basis that they should be used for distributing famine food only. This was despite the fact that Lake Frey’s Bill of Landing receipt bore no evidence of food supplies. The Russians may have had the trucks. They just didn’t have the food to put in them.

Curiously, in September 1919, shortly after one of its London officials cabled Captain Martin to redirect supplies to Yudenich Forces, the London Office of the American Relief Administration was wound down and several officials, including Herbert Hoover, Robert A. Taft and Commander George Barr Baker travelled back to the United States. [67] The Administration’s Paris offices were closed at the end of August 1919.

Was there a political dimension to the accusations that Scaife and Watson were making against the A.R.A and Herbert Hoover? It’s certainly a reasonable question to ask, and in all likelihood, it was probably so. But there were other factors too that were likely to have been a little more mercenary and self-serving.

Senator Thomas E. Watson, the man who initiated the charges against Hoover and the American Relief Administration had enjoyed a long and tempestuous political career, first as a Democrat and then as a tough, belligerent and unashamedly racist (and anti-Semite) Populist with one serious axe to grind. In 1896 Watson ran as Vice President during William Bryan Jennings’ White House campaign. Despite breaking from the Democrats some twenty-years earlier his ‘unconditional rejection of the League of Nations’ won him the Democrat seat in the Senate for Georgia. His claims about the A.R.A were clearly part of a broader scheme to undermine public trust in US peace efforts. [68]

Sadly, Senator Thomas E. Watson never lived to see whether or not his efforts would pay off. In September 1922, just twelve weeks after launching a Senate investigation into Herbert Hoover and the American Relief Administration, Watson died suddenly at home in Washington.

Making sense of the allegations in a world that no longer possesses the same emotional and economic paradigms that super-charged the accusations back in 1922 is an almost impossible task. Americans at this stage had formed no firm concept of Lenin’s Soviet. The Cold War was still some thirty-years off and just four years earlier, Russia had been America’s ally in the war with Germany. For men like Watson, the Bolsheviks represented a legitimate, although far from ideal, grassroots challenge to the tyranny of Imperial Russia. In Watson’s estimation, men like Herbert Hoover were stifling the ‘Will of the People’ before it had ever really had chance to breathe. Even so, there were historical (and also the crudest of political) dimensions to all this too and it may be sensible to remember that Watson’s 1896 running mate, William Jennings Bryan, had also featured prominently in the early life of Captain James Vernon Martin — the man at the centre of Watson’s claims about Hoover and the A.R.A.

Why did Martin Expose Hoover?

Everything taken on balance? Probably not, it has to be said. The screeches and rasps the Senate heard back in the summer of 1922 weren’t the chirr of collective anger, they were the wheels of power turning. There was little in the way of a conspiracy here. Wall Street didn’t invent Bolshevism, and contrary to what writers like Antony C. Sutton might argue, I see little evidence that the Entente powers ever set-out to destroy Russia as an economic competitor. If anything, there seemed to be considerable effort among allied brokers to transform post-Imperial Russia into a credible and modern trading partner — something which had been practically impossible during the rule of the Tsar, Nicholas II.

The ‘fountain of petroleum’ discovered between 1904 and 1910 had led to a flurry of British company formations. Among those rushing to plunge their taps into Russia’s generous underground reservoirs, were the Anglo-Maikop Corporation, The Maikop and General Petroleum Oil and Producers Limited, The Scottish-Maikop Corporation and Spies Petroleum — a syndicate consisting of directors Sir Griffith Thomas, Dr. Ernest Hirsch, Hugh Law MP, Edward Stanley Ormerod and Sir Edward Durand. Situated on the western tip of the Caucasus, the Maikop oil field’s proximity to the Black Sea made it ideally placed for shipments. Spies Petroleum had started expanding its oil interests from Russia’s Grozny region to Maikop shortly after the First Revolution of 1905. Russia’s oil and mineral wealth was considerable, yet in areas like Maikop, its reserves remained largely untapped. In 1916, Pyotr Bark, the Tsar’s Finance Minister said this of Russia’s vast mineral resources, “There can be no doubt that the Empire of Russia will prove a fruitful source of exploitation for British Capital after the war and that Russian and British interests will be united in the most intimate fashion.” [69]

Immediately prior to the Second Russian Revolution in March 1917, the company’s oil production had dropped from 211,434 tons in 1915 to 136, 286 tons in 1916.[70] After the revolution some stability was maintained and production looked set to increase. [71]

In July 1917, George Tweedy of the Anglo-Maikop Corporation offered a withering critique of the ‘hampering’ regulations placed on oil development by the recently deposed Tsar, hoping that the ‘new Russian Government would appreciate the benefits to the nation of adopting new laws and regulations and encouraging the development of these oilfields’. Tweedy went on to explain how the Tsarist regime had squandered significant opportunities from speculators. [72]

In the United States, The Washington Post reported that there was a ‘scheme to transfer’ Russia’s vast mineral resource to America. It coincided with news of a further $100,000,000 loan to Russia from the United States Government. [73] The decision had been reached during the stay of the Elihu Root-led American Mission in Petrograd during the summer of 1917.

Just months after the February Revolution and several weeks before Lenin’s October Revolution, H.D.L Minton of the Chamber of Commerce had embarked on a series of lectures around the North of England highlighting the opportunities that Russia’s immense mineral reserves offered British Traders. [74] Again, the central issue was about stability and closer contact.

The Tsar’s failure to establish stability in the Baku region had meant oil prices were in a constant state of flux. Bolshevik activity during the 1905 Revolution and Azeris/Armenian tribal tensions resulted in declining production and rollercoaster oil prices. [75] The editor of Petroleum World described it as ‘the most awful blow that has fallen on the industry since oil has been pumped from the earth’ and he also expressed the fear that vast fields may be reduced to ashes. Attempts to reform and modernize the Tsarist regime had failed. By 1916, the severest of the fault lines had already begun to appear and it was clear that banks and syndicates from all corners of the globe were making plans and provisions for a number of possible outcomes — and it’s inevitable that opportunities to influence those outcomes when they arose were going to be taken. Securing the Baku oilfields and railroads from the advance of Germany and Austro-Hungary was one thing, securing it from the kind of strikes, hijacks and seizures we saw in the Libyan Oil Crescent in the aftermath of the 201 civil war presented an altogether different series of challenges. The preferred outcome had failed to materialize. Tough economic realities would have to be faced and overcome. And so would the Germans, whose peace agreement with Lenin’s Bolshevik Government looked set to undermine all these efforts.

Within months of Russia and Germany signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, some were beginning to feel that Germany would be prepared to accept any peace deal being offered, provided she was free to exploit Russia’s inexhaustible mineral supplies. [76] Exiled journalist Dr. David Soskice claimed that Lenin had told the Soviet Executive Committee that Russia was pledged to pay a 6,000,000,000 rouble indemnity to Germany. To pay it, it would be necessary to hand over practically exclusive rights to exploit its minerals. Edward Legge, writing in The Graphic, regarded the full economic tragedy of a German and Austrian advance into the prosperous gold region of Siberia. If successful, Germany would have at her disposal “untold wealth, riches, inexhaustible, fabulous.” [77]

In July 1919, some two years after the revolution, the Sheffield Daily Telegraph was reporting that over 7,000 Germans were now occupying senior financial and technical positions in the newly established Soviet Russia. [78] The same concerns were raised in The Times. [79] Fears about German trade with Russia only deepened with a report in a Paris newspaper that the Leipzig’s Council of Workers was sending 800,000 unemployed Germans to work in Russia. Once there, it was said, factories would be placed at their disposal and they would have the privilege of acquiring Russian nationality. [80] The Times of London was reporting that Berlin was already issuing a paper published in the Russian language, and that there had been an invitation to Russia to regard Germany as her second home. [81]

The feeling that was emerging right across the political divides in Britain was that allowing exclusive trade to flourish between Germany and Soviet Russia was not in British interests. Lieutenant Commander Joseph Kenworthy was to address this issue in Parliament; how were we to insure a fair chance for British merchants and manufacturers in Soviet Russia if the Germans were allowed to “capture the markets”? [82]

Planned or not, the developing trade relationship between Lenin and Germany had dealt a huge blow to Pyotr Bark’s predictions of great post-war intimacy between Britain and Russia. Attempts to use the existing Relief Mission to support a crisis-point advance on Petrograd were clearly one last throw of the dice for the allies.

The route taken by Churchill and Hoover back in 1919 would have been an inevitable response to a curveball of truly epic proportions. The understandably cautious attitude shown by President Wilson and Lloyd George’s to all-out war with Lenin’s Soviet would be repeated by Neville Chamberlain to just as great a cost some twenty years later. To tireless and underappreciated idealists like Martin and Senator Thomas E. Watson, the appeasement shown to Lenin’s Bolsheviks by President Harding and Herbert Hoover would have seemed like nothing less than betrayal, and the millions misplaced in the funds, a swaggering abuse of power.

When James V. Martin made his claims against Hoover and the American Relief Administration he had already embarked on a series of legal challenges over patents. At twenty years of age Martin had found himself at the crazy, pulsating centre of progress and innovation. And by the mid-20s he was yesterday’s man: his ideas and inventions had inspired millions of dollars, but which had earned him practically nothing. For people still seeking to make their fortune like Martin, having vast invisible fortunes moved around the board like checkers by powerful men like Hoover must have seemed like a mocking injustice. Martin spent the next thirty-five years filing one patent infringement case after another, slavishly pursuing his claims through the courts. “When Will Merit Count in Aviation?” he asked in 1924. And in Martin’s case it never did. He’d gambled the spoils of invention on a double dozen bet and the chips he’d placed were his ideals.

Nobody could have anticipated the turn of events in October 1917. Lenin’s ‘Sealed Train’ return to Russia would change Russia and the world forever. If only there had been the ‘wrong kind of leaves’ on the line that day.

[1] Proceedings and Debates, Second Session of the Sixty-Seventh Congress, Congressional Record-Senate, May 25-June 13 1922: Vol. 62, Washington Government Printing Office, 1922, pp. 8249-8252; ‘Secret War Pact’; Daily Herald, April 2 1924, p.3

[2] ‘Harvard Aviation Meet’, Boston Post, September 2nd 1911; ‘The Wonderful Science of Aviation’, St Johnsbury Caledonian, August 16 1911, p.10

[3] ‘War Office Air Tests’, Daily Mail May 8 1911

[4] Racine Journal News, 28 February 1916, p.30

[5] ‘Aerial Patrol Station Given to Government’, The Daily Missoulian, Vol. XLII, No.335, March 31, 1917, p.1

[6] Racine Journal News, 28 February 1916, p.30. The claim about his time aboard the SS Red Cross is made in the report of an address that Martin makes to the National Security League, but I have yet to see any firm evidence. It certainly makes sense in the context of his special relief mission to Reval.

[7] Proceedings and Debates, Second Session of the Sixty-Seventh Congress, Congressional Record-Senate, May 25-June 13 1922: Vol. 62, Washington Government Printing Office, 1922, pp. 8249-8252; ‘Probe Hoover War on Soviets’, Ship Capotain Tells The Dogherty Probers, Vol. II, No.16, The Daily Worker, April 4, 1924, p.1

[8] Hansard, House of Commons, Chamber Orders of the Day Army Estimates, 1919–20, 29 July 1919 Volume 118

[9] ‘Trade Unionism and the Army’, Full Text of the Extraordinary Document, Daily Herald, No.1,030, May 13, 1919, p.1; ‘Churchill Adamant’, Secret Circular Part of Military Regime: Kolchaks Troops in British Uniforms, Daily Herald, No.1,045, May 30, 1919, p.1

[10] Leadville Herald Democrat, 07 January, 1921, p.2

[11] The Rise Of Herbert Hoover, Walter W. Liggett, The H.K. Fly Company Publishers, 1932

[12] ‘Our Mr Urquhart’, Daily Herald, No. 1,085 July 16, 1919, p.4

[13] ‘Anglo-American Loan to Omsk’, The New York Herald (European Edition Paris), April 1, 1919, p.1

[14] Samuel McRoberts’ fight with Bolshevism continued well into the 1920s. At the end of 1919, as America and Britain began to pull out of Russia’s civil war, McRoberts was made treasurer and director for American Central Committee For Russian Relief Inc (its acting secretary was Alex Kaznakoff) Based in General Grant’s former HQ at the Old War Building in Washington, the Committee was set-up to fill the void left by the temporary suspension of Herbert Hoover’s American Relief Administration.

[15] Frank A. Vanderlip is not to be confused with the peculiar story of the mining concessions awarded to his namesake, Washington Baker Vanderlip by Lenin in 1920 — although I dare say there is some discreet but no less extraordinary overlap

[16] ‘Concessions to Britain and America’, Manchester Guardian, Apr 2, 1919, p.7

[17] Leadville Herald Democrat, April 19 1919 Associated Press; ‘Anglo-American Loan to the Omsk-Government’, The Scotsman, No. 23,662, April 2 1919, p.7

[18] According to Jechalski’s friend, civil Liberties lawyer, Arthur Garfield Hays, Jechalski entered the US in 1915-17 to negotiate a contract with Poole Engineering for artillery mountings and Maklan guns for the Tsar’s Imperial Guard (re-appropriated by Lenin’s Red Army in 1918). Jechalski was also the conduit in getting Romer’s geographical statistical atlas to Wilson in time for the Paris Peace Conference. The map was central to the political and economic mapping of the national borderlands under negotiation.

[19] Hoover Institution Archives, Russia, Posol’stvo, File 370-12

[20] According to contemporary editions of The Methodist Yearbook, Bysshe would superintend the Methodist Episcopal Church Missionary Society in France, and Simons in Russia. Both men were members of the executive committee and editors of its journals. In February 1919 Simons would join John Reed, Louise Bryant and Herman Bernstein in a Senate hearing investigating Bolshevik Propaganda and pushing both German-Tsarist and German-Bolshevik conspiracy theories. See: Hearings Before a Subcommittee … Pursuant to S. Res. 439 & 469, Feb. 11, to Mar. 10, 1919

[21] The National Archives, National Archives, Correspondence, General, Political, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, PRO FO 371/4019

[22] ‘Congress to Grasp Reins Says Harding/A Guaranteed Investment’, New York Time, May 19 1919, p.10

[23] Boston Post, 08 January 1919, p.6

[24] Ace of Spies: The True Story of Sidney Reilly, Andrew Cook, History Press, 2011, p.134/American Publishers’ Association, 1917, p.273

[25] US Bureau of Investigation/ Office of Naval Intelligence Report, 17 October 1918; Ace of Spies: The True Story of Sidney Reilly, Andrew Cook, History Press, 2011, p.134

[26] ‘Bethlehem Steel Preferred. A Bethlehem Story’, New York Times 25 February 1917, p.3

[27] One of the more notorious figures at the Russian Supply Committee in New York was Lieutenant Boris Brasol, believed to have provided the first US translation of the anti-Jewish forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in 1919. He also worked closely with Henry Ford on Dearborn Independent. Brasol had worked as a lawyer at the Russian Supply Committee since 1916. Just three years earlier he had had served as lead prosecutor in the 1913 the equally anti-Semitic Beillis Case, in which a Russian Jew was accused of the Blood Ritual murder of a Christian boy.

[28] ‘Committee of America Disowns Offer to Represent Petrograd Government: Zemstvos Agents Win Out’, New York Times, 18 March 1917, p.3

[29] Memoirs of a British Agent, R. H. Bruce Lockhart, Putnam, 1932, p.124

[30] ‘Recognize the Omsk Government!’, New York Times, 09 June 1919, p.9

[31] Soviet-American Relations, 1917-1920, Chap. XIV: Private American Influences, George F. Kennan, Princeton University Press, 1958, pp. 331-334

[32] Philadelphia Inquirer, 03 October 1918, p.24

[33] William H. Coombs, U.S. State Dept. Decimal File, 861.51/752

[34] Donovan: America’s Master Spy, Richard Dunlop, Skyhorse, 2014

[35] ‘Russi & Japan: Cheltonian’s Interesting Accounts’, Cheltenham Examiner, 22 June 1904, p.6

[36] The National Archives, The Security Service: Personal (PF Series) File, Sidney George Reilly, KV-2-827,

[37] It was Churchill (serving as British Secretary of War in 1919) who appointed Morton to Section V of Mi6 at the beginning of April 1919 (taken over officially on April 23rd 1919). The two men were great friends. In 1940, Desmond Morton became Churchill’s Personal Assistant at 10 Downing Street. Churchill even ended up living in the house that Morton was born in.

[38] The National Archives, The Security Service: Personal (PF Series) File, Sidney George Reilly, KV-2-827, ‘Wire from New York – Mr Reilly Sailing in SS Baltic’, 11/04/1919

[39] William Bullit ended up marrying the widow of journalist ‘revolutionary’ John Reed, whose book, ‘Ten Days that Shook the World’ (March 1919) provided a firsthand witness account of the 1917 Revolution. The book helped shape the accepted narrative of events for years to come. Reed’s widow Louise Bryant, herself an activist, wrote ‘Six Red Months in Russia’ (1918).

[40] Reilly: Ace of Spies, Robin Bruce Lockhart, Penguin, 1984, p.109

[41] Reilly: Ace of Spies, Robin Bruce Lockhart, Penguin, 1984, p.108

[42] SiS HD files, Reilly Papers CX 2616, 13.03.1920

[43] SiS HD files, Reilly Papers CX 2616, 03.10.1919-16.10.1919

[44] Hansard, Statement by the Prime Minister, Malone MP, House of Commons, 10 August 1920 Volume 133

[45] What Happened to Europe?, Frank A. Vanderlip, Macmillan Company, New York, July 1919

[46] What Happened to Europe?, Frank A. Vanderlip, Macmillan Company, New York, July 1919, p.154

[47] London News (Column Two), The Scotsman 18 January 1917, p.5. Also see the journal of National City Bank employee, Leighton Rogers for a witness account of the Revolution — Leighton W. Rogers Papers, Library of Congress

[48] ‘Denied By Hoover’, New York Times, September 12, 1922, p.7

[49] ‘Hoover Talks About Russia’, The Caldwell Times, May 26, 1922, p.4

[50] ‘Russo-Asiatic Corporation Limited’, The Times of London, December 19, p.1

[51]‘The Man Who’s Feeding Europe’, Sheffield Weekly Telegraph 15 February 1919, p.3

[52] ‘Inquiry Shows Claims That Hoover Sabotaged Russian Relief False’, Walter Lippmann for the New York World, St Louis Post Dispatch Sunday Editorial, May 14, 1922, p.3

[53] ‘Watson Flays Hoover before U.S Senate’, American Guardian, June 15, 1922, p.2; ‘Watson Charges Hoover’, Times Herald, May 31, 1922, p.19

[54] ‘Basis to Indict Alleged: Scaife Names War Secretary, Daugherty, Goff and Hayden of Wright-Martin Co.’, New York Times, April 3, 1924, p.1. The company was owned by Glenn L. Martin, no relation to James V. Martin.

[55] Leadville Herald Democrat 13 February 1922, p.1

[56] Proceedings and Debates, Second Session of the Sixty-Seventh Congress, Congressional Record-Senate, May 25-June 13 1922: Vol. 62, Washington Government Printing Office, 1922, June 6 1922, p. 8251

[57] James Vernon Martin married Lily Irvine in Paddington, London in 1911, after both had completed training at Claude Grahame-White’s flight instructor school in Hendon, Greater London (Lily became the first English woman to fly solo). Helen’s Grandmother was Lily’s sister, Flora Irvine (born. 1887). The sisters’ father Robert James Croy Irvine (born 1856) and mother, Elizabeth Watson (b.1856) were married in Edinburgh in the early 1880s. Around 1886 (probably at the time of the Witwatersrand Gold Rush) Robert got his passport for the Cape Colonies. The whole family followed in 1890. Robert is said to have lost his business as a result of the Second Boer War (1898-1902) and died in Scotland a short time later.

[58] Documents On British Foreign Policy (1919 1939) Vol. III, ed. E.L. Woodward & Rohan Butler, London His Majesty’s Stationery Office, p.85

[59] Documents On British Foreign Policy (1919 1939) Vol. III, ed. E.L. Woodward & Rohan Butler, London His Majesty’s Stationery Office, p.90

[60] ‘Air Forces in North Russia’, The Scotsman, No. 23,669, 10 April 1919, p.5

[61] Hansard, Commons Chamber, Royal Air Force, 12 August 1919, Volume 119

[62] Trust No One, The Secret World of Sidney Reilly, Richard B. Spence, Feral House, 2002, p.227

[63] ‘The Control of Airships, The Times, August 1st 1919, p.16

[64] Inquiry Into Operations Of The United States Air Services Hearing Before The Select Committee Of Inquiry Into Operations Of The United States Air Services, House Of Representatives, Sixty-eighth Congress, On, Part 3, p. 2458

[65] Major General Ernest Georgievich von Wahl of the Russian Imperial Army (1878-1949). He had estates in Estonia and the Crimea. The episode featuring Martin and Lake Frey are recalled in his memoirs, Воспоминания : Генеральный штаб — Гражданская война — Эмиграция : 1905—1913, 1918—1919 (Memoirs: General Staff – Civil War – Emigration: 1905-1913, 1918-1919, Archives of the Russian Emigration at the Church of the Life-Giving Trinity in Brussels