Alan Bleasdale’s drama, The Monocled Mutineer shows a small contingent of over zealous Red Caps (Military Police) trying to prevent a fractious body of Scottish and New Zealand troops from leaving Etaples Base Camp and entering the local town. During the fracas that ensues, one of the Red Caps draws his pistol and shoots into the crowd, killing Corporal William.B Wood of the 4th Gordon Highlanders (No.240120).

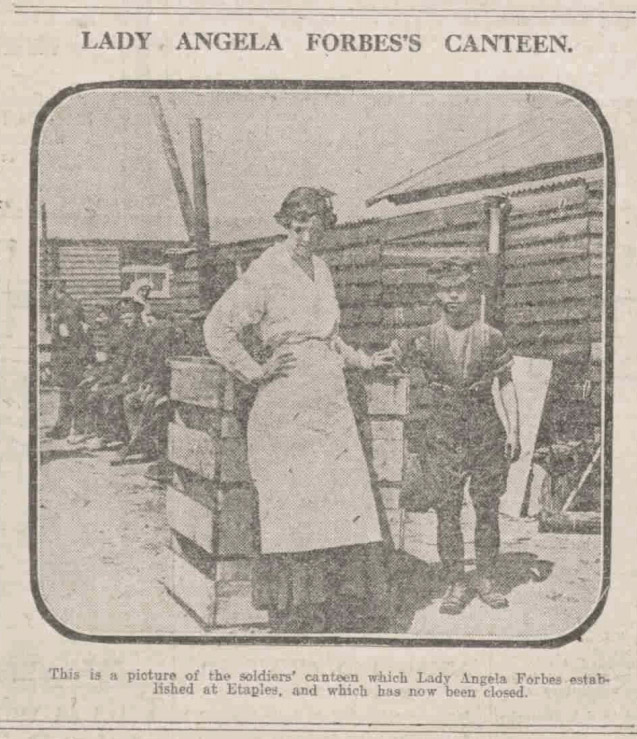

What the drama doesn’t mention is that the Red Cap responsible for shooting Wood, and triggering the subsequent riots, was British champion boxer, Harry Reeve, who had been transferred to the Camp Police just a few weeks prior to the Mutiny. The drama also didn’t mention that it was Lady Angela Forbes, the camp’s aristocratic canteen lady, assisted by her lover, Hugo Charteris, 11th Earl of Wemyss, had been personally responsible for Reeve’s transfer to Etaples as part of the boxing exhibitions she had organized for camp recreation activities. Whatever the extent of her input into the events that happened that week, the authorities were sufficiently concerned to shut down her camp canteen. Discussions about the closure even featured in Parliament and demands for a full investigation were made (see: Hansard, Lady Angela Forbes Canteen, Feb 5th 1918, vol 28 cc380-9)

But who was Harry Reeve, and what are his links to another high-profile legend — the famous Jack the Ripper murders?

The Mutiny

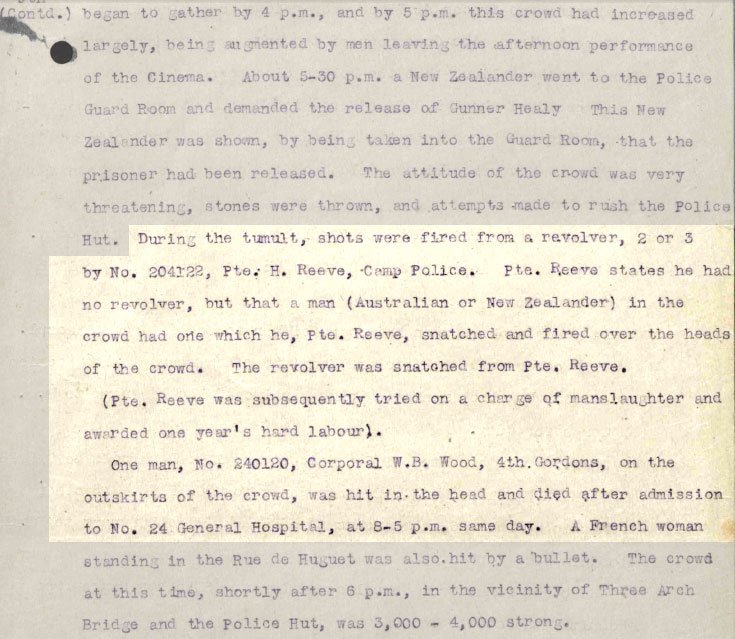

First of all, there is no disputing Reeve’s involvement in the mutiny. The Etaples Base Camp diaries now freely available in the National Archives, describe how Private H. Reeve of Camp Police (No.204122) fired two or three shots from a revolver that resulted in the death of Corporal W.B Wood of the 4th Gordon Highlanders. Wood was hit in the head and died shortly after admission to No.24 General Hospital. Reeve alleged that he had snatched the revolver from the hands of an Australian or New Zealand soldier and had fired over the heads of the crowd. The diary records that Reeve was tried for manslaughter and sentenced to one year’s hard labour (Etaples Base Camp Diaries, National Archives, WO 95/4027/5). In the various accounts that followed, it seems that as the swarming hordes of men furiously pursued revenge, Reeve and his fellow officers stripped-off their Police uniforms and caps and merged with the regular soldiers.

Eyewitness accounts published in the various letters and books in the years that followed are fairly unanimous; the Camp Red Caps were hunted down in all directions, a good number of them being pursued to the nearby town where they were hiding and then beaten. S.J.C.R writing in the Manchester Guardian in January 1930 describes how the killing of Corporal Wood ‘suddenly set-loose all the long accumulated hatred for the Red Caps’. Reeve appears to have targeted a soldier with the New Zealand regiment who was strolling over the railway bridge toward Etaples with his arm round the waist of a WAAC. An altercation ensued and the soldier (Gunner Healy) was arrested and detained. Attempts by ‘the usual group of soldiers hanging about on the outskirts of the camp’ to free the soldier resulted in the man making a desperate dash for liberty by diving into a mass of Gordon Highlanders who had gathered around the police hut. Reeve, ‘pestered and excited’, is said to have drawn his revolver, fired at the fugitive, missed him and instead killed Corporal Wood. A French woman standing nearby was also hit by a bullet.

According to Lady Angela Forbes, Reeve managed to escape through the back of the detention compound and made his way to shelter at the station. Brigadier Thomson’s records show that 3,000 – 4,000 men began to gather in the vicinity of the police hut and Three Arch Bridge. According to a letter published in the Aberdeenshire Press and Journal in 1930, several MPs were either ‘stoned or shot’ (Aberdeenshire Press and Journal , February 17th 1930).

Author Vera Brittain, a nurse serving in No.24 General Hospital at the time of the Mutiny, describes in her 1931 memoirs, Testament of Youth how an officer was also found dead in the Bull Ring.

An account provided by A.B Newland of the Church Army Canteen in 1922 painted much the same picture; there had been constant friction between the men and the camp police. There’d also been the grueling daily torture and humiliation of the notorious training ground, the ‘bull ring’. Newland goes onto say that it was only the timely intervention of John Bull editor, Horatio Bottomley that saved the day.

Bottomley, MP for Hackney in East End London, was generally regarded as one of the soldiers’ truest and most trusted allies. As ‘crisis crusader’ he had received special permission to tour the battlefields and base depots of France that week. By some stroke of fate he just happened to be on stand-by when the disturbances at the camp broke out. On his return to England he was able to write on October 6th that he had discussed with General Haig the main matters of complaint: ‘Leave, Pay, Field Punishment, Military Policing, Short Rations and Cushy Posts ’ (John Bull, October 6th 1917). The metaphor he used to frame his optimism about the fighting couldn’t have been more appropriate; ‘If politicians would just kindly keep out of the ring’ Germany would be swiftly beaten (John Bull, September 22nd 1917). In June 1920 he would tell the same readers that soldiers were treated like slaves during the war, losing all civil and natural rights, merely for the ‘crime’ of serving his country. Bottomley wrote, “The men who have suffered have come home, and they have been quietly and mercilessly been sent to the same fate as the Crimean veteran.” He uses the example of an officer court-martialed and executed for losing his nerve in battle.

Whatever the truth of some of the details, what had begun as a minor camp disturbance over the detention of an Anzac soldier had developed into large-scale rebellion.

Born Harry Isaacs to Jewish parents Louis and Henrietta (neé Behrendt — her father was German) in Mile End in 1893, Reeve was winner of the famous Lonsdale belt for light heavyweight bouts during the early 1900s. This detail is crucial, as two separate witnesses to the events at Etaples that week claim that the man responsible for killing Corporal Wood was a well known British Heavyweight and Lonsdale-belt winning boxer. The men making the claim were Lancashire Fusilier, George Souter, who shared his account in a letter to The Manchester Guardian (14th February 1930) and Etaples Mutineer, James Cullen, who wrote his own account of the riots in the Glasgow Weekly Herald (February 19th 1927, p.4)

In a peculiar twist though, it transpires that Private Harry Reeve had been serving with the Etaples Camp Police only a matter of weeks before the riots. The reason behind Reeve’s his disastrous transfer has so far remained a mystery.

Reeve was conscripted into 4/10th Middlesex Regiment in May 1916 (The People, 28 May 1916, p.16). At this time he was still fighting in the ring competitively. The ’bout of flu’, which had delayed his departure to the front line in France may well have been may well have been a consequence of last-minute sporting arrangements (Illustrated Police News 15 March 1917, p.8). In July he would face Sherwood Forester Sergeant Harry Curzon DCM (Daily Record 27 July 1916, p.5) and in September he was scheduled to take on Bombardier Billy Wells (Daily Mirror, 07 August 1916, p.11).

In recent years doubt has been expressed that Reeve had ever served as a formal ‘Red Cap’ (Military Police). Some have tried to argue that Reeve had been drafted in and assigned, perhaps temporarily, to carry out lesser duties on behalf of the Military Police. Any attempt to pursue such a distinction is, however, likely to lead nowhere. The terms appears to be virtually interchangeable. Temporary transfers to the Military Foot Police were a common and routine affair, and requests were duly weighed up and granted by Provost Marshals, based on the skills (and size) of the soldier making the request. In the absence of a contingent of formally designated officers, soldiers might, from time to time, and in battlefield situations, perform the duties of ‘Camp Police’, but this legendary Base Camp that possessed all the organisation of a major training ground and depot, hardly fits that bill. In the various eyewitnesses accounts, the Police at Etaples Base Depot are referred to as ‘Camp Police’, ‘Military Camp Police’, ‘Foot Police and ‘Red Caps’ in a fairly loose and arbitrary fashion. The camp diary describes Reeve’s rank as Private. The default rank for the Military Foot Police was Corporal, but all soldiers who had undergone court martial were stripped of their rank and reduced to Private, so attempts to take anything from this alone are further complicated by the quirks of protocol.

How long had Reeve been serving with the Camp Police? We’re not sure. He is certainly appearing in press reports of his adventures as Corporal Harry Reeve of the Middlesex Regiment in April 1917. ‘Riverside’, a columnist for the Green ’un newspaper writes on August 18th 1917 that he has just watched Reeve playing cricket among the dunes in France. He mentions that Reeve was still boxing up to ten rounds a night “with anyone he can find good enough to make a show” (Star Green ’un, August 18th 1917, p.5). In a later edition of the paper, dated 12 January 1918, there is an oblique reference to Harry Reeve being “out of the way, and of the war” (p.7). It may be a cloaked, sideways swipe at Reeve’s recent court martial and detention, but equally it be something more trivial.

Whatever the truth of his transfer, one thing is certain; by September 1918 Reeve was back home in England and convalescing at North Evington Military Hospital in Leicester after being wounded in action (Leicester Daily Post, 09 September 1918, p.3). Despite the sentence of 12 months’ hard labour awarded by Brigadier Thomson and described in the Base Camp diaries, how much time Reeve actually served (if any) for the killing of Corporal Wood is not known.

His injuries can’t have been too life-threatening as by November 1918 he was back in the ring at a charity bout with Frank Goddard (Yorkshire Evening Post 26 November 1918, p.3)

The Boxer

Was Reeve an ‘agent provocateur’, installed deliberately at Etaples to trigger the famous riot? It’s really very difficult to tell, but there are several details in his life-story, both before and after the mutiny, that make it plausible. The first is Harry’s contact with the East End underworld, and the second his family links to Ripper witness, Charles Reeve and Reeve’s daughter Ada Reeve, the famous music hall and film actress.

Reeve’s original boxing manager was Dan Sullivan, a bookmaker who later worked for the dubious bagman, swindler and fallguy, Dick Burge at the Blackfriar’s ring, before managing and training East End gangster and extortionist, Darby Sabini — recently revived as a character in Season Two of Peaky Blinders. Both Sullivan and his promoters, Dick and Bella Burge were prominent figures in the East End underworld. In the early 1900s, Burge had served several years in jail for bout and racetrack rigging. He was also suspected of embezzling £200,000 with American broker Lawrence A. Marks of commission agents, L. Marks & Co through the Bank of Liverpool on behalf of powerful Jewish bankers, who were believed to have held substantial stakes on the London Stock Exchange (see: Old Bailey, Thomas Goudie, Richard Burge, Deception: Fraud. 10th February 1902). Dick’s wife Bella Burge later hired East End gangster, Jack Spot Comer at the Blackfriar’s ring (there is a great story of Comer and his mob charging into Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists during the so-called ‘Battle of Cable Street’ in October 1936). Years earlier, Harry’s father Louis had lived at 315 Cable Street with wife Henrietta and his mother-in-law.

Reeve’s first serious encounter with Burge took place shortly after his return from a competitive of tour Australia in January 1916. Burge lined Reeve up to challenge Bombardier Wells at the Drury Lane theatre, in a £500, twenty-round bout.

In a curious parallel, it seems that whilst Burge had enlisted with the 21st Battalion London Regiment in 1915, he too was transferred, at his own request, to the Military Foot Police on 31st August, 1917. The transfer took place just days before the Etaples Mutiny.

Did Burge’s appointment have any connection to Reeve’s transfer to the camp police during this same period? It seems likely given the strong professional bond between the pair. But more to the point; what motivated the pair’s transfer?

Interestingly, Toplis detective, Edwin T. Woodhall was similarly transferred from Military Intelligence to the Military Foot Police in the immediate aftermath of the mutiny. His transfer to the Court Martial Prison and Detention Camp came with the task of rounding up deserters, absentees and tracking down the most violent rioters who had set-up their headquarters in around the woods and sand dunes of Paris Plage and Berck (Detective and Secret Service Days, 1930).

Despite the peculiar sequence of events, it’s worth noting that Burge served with the Military Foot Police in the London district, whilst Reeve served with the Base Camp Police in France.

In the last week of March 1918, Reeve’s promoter Dick Burge caught pneumonia. A few days later he was dead. 4,000 people attended his funeral, carried out with full military honours, at Golders Green Jewish Cemetery. His coffin was carried by his comrades within the Military Foot Police. The mourners included the Percy Douglas, 10th Marquess of Queensberry, William Montagu, 9th Duke of Manchester, British socialist and trade union leader, Ben Tillett, Joe Elvin (Founder of the Grand Order of Water Rats) and Chief Inspector William McBride of Scotland Yard. Dick’s wife Bella even received a message of sympathy from the King and Queen (Funeral of Famous Boxer, Daily Mirror 20 March 1918, p.2).

Ben Tillett’s attendance is a curious one, as it was Tillett, Guy Bowman and Tom Mann who had been largely responsible for the infamous 1912 Don’t Shoot pamphlet — an article requesting that troops should mutiny in the event of a national coal strike.

Tillet’s friend, Victor Grayson, very nearly arrested himself during the Don’t Shoot affair, marched into Etaples with the New Zealand Canterbury Regiment on the very day the mutiny took place, and in the very same section of the camp that the mutiny erupted (the Reinforcement Camp: WO 95/4027/5). You can read his story here.

Burge’s sporting, bloodstock and sweepstake links with John Bull editor and Hackney South MP, Horatio Bottomley, who also arrived at Etaples that week, may also warrant closer attention as like Burge, Bottomley also enjoyed the support and patronage of Labour leader Ben Tillett, who was guest editor of his signature rag, John Bull on several occasions.

I also couldn’t help but notice that British Spy, John Baker White, who was to join former Communist and Etaples Mutineer James Cullen at the British Fascisti in the mid 1920s, was also a friend of Etaples Mutiny ‘champion’ Horatio Bottomley. Like Reeve, White had been started his career as a boxer at Burge’s Blackfriars Ring and was a diligent and active anti-Bolshevik campaigner.

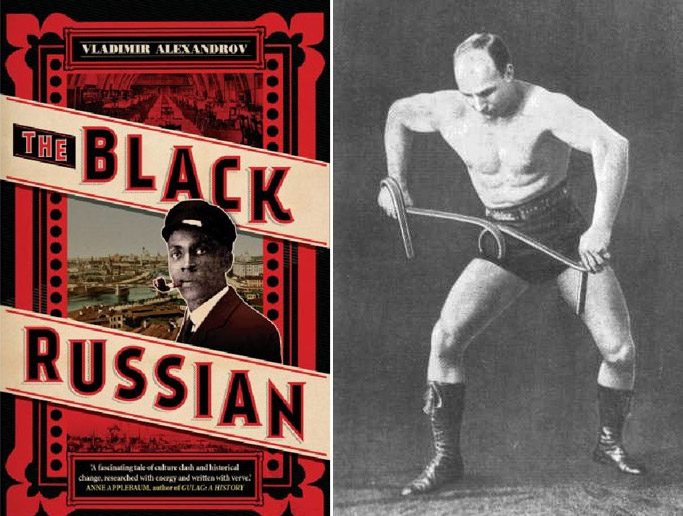

The German Promoter

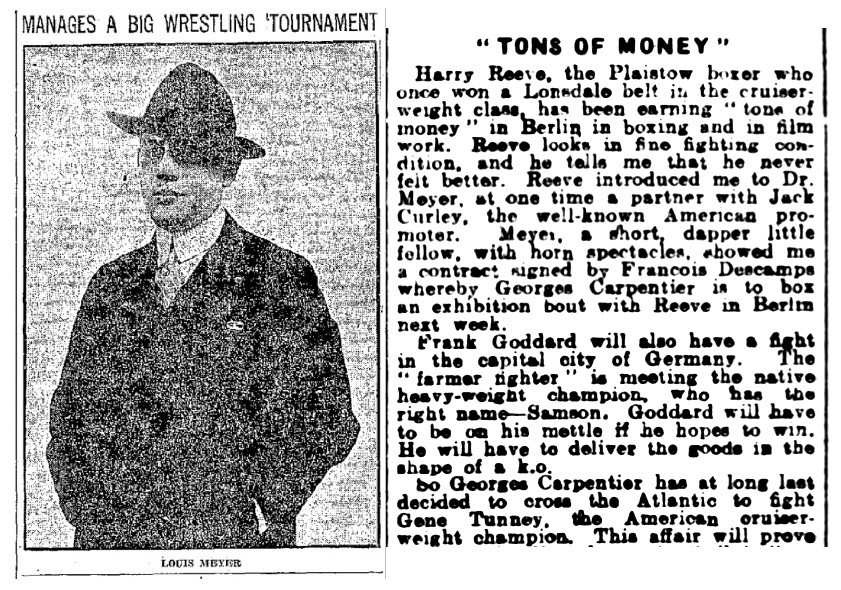

Reeve’s post-war manager was German-American, Dr Louis Meyer. Meyer was described as a short, dapper man with horn-rimmed spectacles. At one time Meyer had been the wrestling and boxing partner of French-American, Jack Curley, former manager of first black heavyweight boxer, Jack Johnson. Interestingly, Johnson is alleged to have been invited to spy on Rasputin during a trip to Russia in 1916. The trip is said to have been arranged by Frederick Bruce Thomas (aka Fyodor Fyodorovich Tomas), the so-called ‘Black Russian’ who had prospered as a theatre-mogul and businessman in St. Petersburg after leaving London in the late 1800s. Thomas would later tell an American Consul that his stay at a music conservatory in London had been facilitated by Thomas’s German music professor (Herman). Johnson is also believed to have dated German spy, Mati Hari (The Black Russian, Grove Press, Vladimir Alexandrov, 2014). Harry’s cousin, the actress Ada Reeve talks about meeting Johnson in her autobiography, Take It For A Fact.

By 1924 Reeve was making ‘tons of money’ in film and boxing work in Germany in bouts and film parts organised by Meyer. Reeve’s first movie, The Door That Has No Key (1921) had been directed by American actor and former stage man, Frank Hall Crane. The film, which is said to have featured a thrilling battle between Harry and Australian Heavyweight, Victor McLagen, had been produced by the Alliance Film Corporation (The Era 02 March 1921).

Alliance Film Corporation Ltd had been set-up in response to the requests of Home Office Intelligence man, Sir Charles Edward Troup for an Intelligence and propaganda arm in Britain’s Film and Theatre industry. Intense paranoia about German and Jewish dominance in the industry had already resulted in the shelving of one big budget movie. Plans to release The Man Who saved The Empire had collapsed at the last moment when Etaples hero, Horatio Bottomley accused the film’s producers, Ideal Films Company, of radical and unpatriotic intent; they were accused of being German Spies (The Manchester Guardian, 14 Dec 1918, p.9). According to the film’s producers, the British Government handed them£20,000 in cash by way of losses and the negatives and prints were seized.

The actual particulars of incorporating, Alliance Film Corporation on behalf of the Secret Service were left to Alfred Baldwin Raper — Conservative MP, Air Force Officer and close friend of Sidney Reilly ‘Ace of Spies’. The company, which had a very short lifespan, was intended to be a multi-million pound, all-British producing movie company (The Bioscope 25 September 1919, p.20). According to press releases at the time, the object of the company was to ‘ensure that a fair share of the world’s film trade shall come to this country’ (Daily Herald 18 September 1919, p.2). Theatre impresario and soon to be elected Conservative MP, Sir Walter de Frece was brought in as Chairman. Its real directive, as proposed by Sir Edward Troup, in a Report of the Secret Service Committee dated February 1919 was to provide ‘some form of propaganda against Bolshevism in this country and a way of communicating the message to the public discreetly.’ He underlined ‘cinematogaphy’ as one of the most desirable options (Report of the Secret Service Committee, February 1919, National Archives, reference KV4/151, p.159-168).

The company’s chairman Sir Walter de Frece had previously worked alongside Horatio Bottomley and Harry’s cousin Ada Reeve at the The Aged Home for Jews in Hackney. Bottomley sat as chairman and de Frece, Ada Reeve and Dan Leno (among others) provided the musical entertainment (The Referee, 11 May 1902, p.4). Bottomley also featured in 1916 film, Truth and Justice, in which he introduced six stories highlighting social injustice. The film was produced by the Birmingham Film Company and syndicated by de Frece (The Bioscope 30 November 1916, p.113).

Not surprisingly, the man chosen to head and direct all Alliance Film Corporation productions was Sheffield man, Harley Knole, director of the 1919 propaganda movie, Bolshevism on Trial (Mayflower Photoplay Company, USA). The film’s writer Cosmo Hamilton was an old Royal Naval Air Service colleague of Raper and had premiered during the first Red Scare in America in April 1919.

Sadly, all the reels and negatives of Reeve’s film for the Alliance Film Corporation appear to have been lost. The film proved to be one of only a handful of films made by the company between 1920 and 1922.

Reeve’s boxing manager, Louis Meyer later went onto manage The Great Zass of Russia – a legendary ‘Iron Samson’ (Lancashire Evening Post 30 November 1935, p.5). Alexander Zass had been born in Vilius in the 1888. It was subsequently alleged that Zass was a spy working for Russian military intelligence.

The Berry Brothers, whose Worlds Pictorial News who published the biggest and most salacious exclusives on suspected mutineer, Percy Toplis started their publishing career in boxing. They were also close political allies of War Secretary Winston Churchill (they helped support the Churchill family, financially too). The brothers were Gomer Berry, 1st Viscount Kemsley and William Ewart Berry, 1st Viscount Camrose. Their brother Seymour handled munitions deals with the US for Churchill during the latter stages of the war.

Charles Reeve and The Ripper

The uncle of Harry Reeve, was music hall actor and comedian Charles Reeve. Reeve had been born in Norwich and was co-founder the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee at the time of the Ripper Murders. By 1891 Charles and his family were living at 209 Jubilee Street in Whitechapel. The famous Jubilee Street Club (also known as the Anarchist Club), was based just down the road at 165 Jubilee Street. There is little denying that the Etaples Mutiny is inextricably wound-up in the broader context of Russia’s 1917 Revolution, so the proximity of the Reeve family and the Club is curious to say the least.

The Jubilee Street Club was a hotbed of Russian socialist and anarchist ideas. After several years on Berner Street, the Club had moved to the New Alexandra Hall. The Club provided space for debate, functions and meetings, as well as an anarchist Sunday School. The club was also the setting for one of Lenin’s first ever speeches in the city and played a key role in the development of the Russian and German Revolutionary and Anarchist movements.

Reeve’s proximity to the club though, is only one in a number of ironies and curiosities relating to the Ripper story.

According to his Ripper Casebook entry, Reeve was almost certainly the ‘Reeves’ mentioned in several newspaper articles and the first man to have examined the famous ‘From Hell’ kidney at George Lusk’s residence on October 17th, 1888 (casebook.org, Notable People, Charles Reeve)

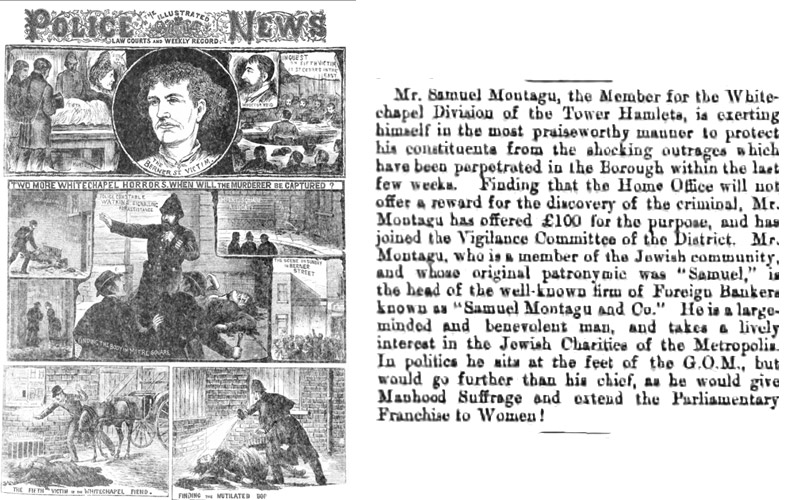

The Casebook also writes that on September 10th, 1888, just two days after the murder of Annie Chapman, Charles became one of several founding members of what would come to be known as the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, a self-appointed neighborhood watch scheme with a sharp, vigilante edge. The group intended to do what it believed the Police couldn’t do: protect Whitechapel’s Jewish community and find and apprehend the murderer. According to statements made to the press, they hired their own detectives and conducted their own enquiries.

As a response to anti-Semitic incidents resulting from the murders, Samuel Montagu, 1st Baron Swaythling offered a reward for the capture of the Ripper. Montagu had spent years trying to improve the social condition of Jews living in the Whitechapel district of London and preventing the ‘anarchy and socialism’ that a small contingent of hardcore radicals had tarred the district with. In a letter to the Home Secretary, the Liverpool-born MP described how the community in Whitechapel had been painfully aware of inadequate policing for some years. “Acts of robbery and violence”, he went on, had been committed with “impunity”. The “universal feeling among them was that the government no longer ensured the security of life and property in the East of London”. Trade in Whitechapel was being destroyed (Eastern Daily Press 19 October 1888, p.3). By mid-September 1888, Reeve and Lusk’s Committee were working closely with Montagu on petitioning the the Home Secretary (Cheltenham Looker-On, 15 September 1888, p.6).

That it was Montagu’s cousin, Sir William Montagu who led the mourners of Dick Burge funeral is certainly intriguing given the war-time relationship between Boxing promoter Burge and Harry Reeve.

The murders at the end of September couldn’t have been better or worse timed, or better or worse located depending on what point you were trying to make. Elizabeth Stride’s body was dumped in the yard of the International Working Men’s Educational Club on Berner Street within two weeks of Montagu joining the Vigilance Committee. Anti-Jewish fever was running high and the ‘Nihlists, Anarchists and Socialist’ of the Working Men’s Educational Club was singled out for particular abuse. Perceptions weren’t helped by the fact that Stride’s body had been discovered by Louis Diemschutz, the Club’s steward. The IWMEC’s founder, Woolf Wess was also called as witness.

Despite being drawn largely from the hundreds of Jews forced into exile from Eastern Europe, these would-be revolutionaries were unwanted on all sides: the Orthodox Jews of the district didn’t want them. The native East Enders didn’t want them.

At the time of the Ripper murders, Charles Reeve was living just around the corner from Berner Street at 5 Thomas Street. This was the street that Constable Neil was walking down when he spotted the body of first victim, Polly Nichols. Reeve’s neighbour at 4 Thomas Street was Richard Irwin and his son, Francis Valentine Irwin. Irwin Snr, from Sligo in Ireland, was serving as Secretary of the so-called Charles Stewart Parnell Organisation, a local London branch of the Irish National League. The ‘East London Hibernian Club and Institute‘, as it was known formally, eventually scored a mention at the trial of Fenian Dynamiter, Robert Anderson. The court heard that informant George Mulqueeny (McSweeney) who played a key role in the case against Parnell in the Phoenix Park murder case, had canvassed at the 1885 elections for Vigilance Committee Chairman, Sir Samuel Montagu. Captain O’Shea, an ‘intimate friend’ of Sir Montagu, alleged that he had introduced Montagu to McSweeney at meetings chaired at the Thomas Street club (The Parnell Commission, Liverpool Mercury 01 November 1888).

The fact that Kelly’s murder took place on the first anniversary of the Bloody Sunday massacre, co-organized by Parnell’s Irish National League, the SDF and the Metropolitan Radical Federation, provides a fascinating parallel. The demonstration, originally planned for Wednesday November 9th — Lord Mayor’s Day — had been deferred to the 13th by Police Commissioner Charles Warren at the behest of the Home Secretary over fears of an inevitable slide into chaos (The Socialists and Lord Mayor’s Day, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper 07 November 1886 p.7)

That the infamous From Hell letter is said to have born all the hallmarks of a strong Irish brogue, or a ‘stage-Irishman’ at the very least, is also a noteworthy feature.

Curiously enough, Hall Caine — the homosexual lover of Ripper suspect Dr. Francis Tumblety — was sent on a ‘special literary mission’ to Russia by Montagu and other patrons of the Russo-Jewish Committee of London in October 1891 (Mission to Russia, Illustrated London News 10 October 1891). Montagu, would also pay several visits to the country during this same period. Caine’s trip, which was to deliver over £100,000 in relief funds for persecuted Jews, coincided with a similar mission to Russia by the Boston Branch of the Nihilist Society (Secret Mission by Nihilists to Russia, Pall Mall Gazette 12 December 1891, p.6). Among the emissaries chosen for the Boston trip were Lev Gartman (aka. Leo Hartmann) the Russian exile charged with complicity in the murder of Tsar Alexander II. Gartman, a former London-based member of the Narodnaya Volya, was entrusted with his own bundle of private dispatches and a sum of over $6000. It’s alleged that Gartman had been assisted in various plots to kill the Tsar by suspected agent provocateur and Tsarist spy, Samuel Tragheim. Now living in London, Tragheim had, like Caines lover, Dr. Francis Tumblety, spent several years in St Louis and New York. In Manhattan, both men had properties on Grand Street.

The surprise Extradition Treaty with Imperial Russia proposed by America’s Secretary of State Thomas Bayard in April 1887 appears to have been triggered by concerns from British Intelligence that another St Louis man, ‘General’ James Dyer MacAdaras had ‘dynamite’ men in Russia (Jubilee Plot). Spies were also keeping a close watch on friends of the Irish Nationalist in London. Surveillance had been intensified ever since MacAdaras had met with Russian Minister for Foreign Affairs, M. De Giers. A resolution was quickly adopted by Leo Hartmann and the Russo-American League to reject Bayard’s treaty (Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser 16 April 1887).

According to the American and British press of the period, the Irish National Party and the Nihilists had been thinking of combining their efforts since the beginning of the 1880s. In June 1882 a plenipotentiary of Fenian delegates arrived from the United States to meet with Nihilists in the Soho district of London to discuss the possibility of an ‘official union’ (Nihilists and Fenians in London,The Evening News, June 05, 1882; p.2). More chillingly perhaps, a report in the London Evening News at the end of May 1888, shortly ahead of the first Ripper murder, alleged that a group of Irish ‘Avengers’ had recently arrived in London in preparation for a whole new terror campaign that was alleged to have the backing and cooperation of the Russian nihilists (New Dynamite Brotherhood: The Avengers, London Evening New, 19 May 1888)

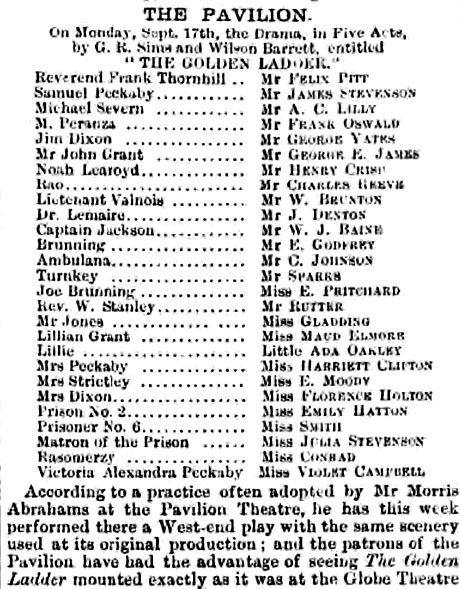

What makes Charles Reeve’s appearance in the story all the more extraordinary is that on the night that Stride’s murder took place, Reeve was acting at the nearby Pavilion Theatre. The play, The Golden Ladder was a righteous morality play, written and conceived by passionate social reformer, George R. Sims, whose criticisms of Police Commissioner, Charles Warren were perhaps only matched in their consistency and ferocity by similar broad swipes Sims made against the Warren for his handling of the “honest radicals” involved in the Socialist riots the previous November (The Referee 04 March 1888, p.5/The Referee 18 November 1888, p.4).

The Golden Ladder played throughout London from Spring of 1888 and had been preceded by the appearance of Sims’ socially and politically driven, How the Poor Live in January that same year (the article appeared in Gilbert Dalziel’s radical comic-strip, Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday (January 28 1888)

The play’s German-educated creator, George R Sims, had been a champion of Social Reform and the Suffrage movement for years. In a bizarre twist, Sims became a suspect in the murders himself, after an obsession with solving the mystery led to a Whitechapel stall holder claiming that the playwright bore a remarkable likeness to a mystery man that he had seen on the night of the Berner Street murder.

It may be worth noting that Sims’ friend and colleague John Burn, was a founding member of Henry Hyndman’s Social Democratic Federation. SDF branch representative John Burns and his colleague, Herbert Burrows were no stranger to the the International Working Men’s Educational Club on Berner Street, having been among a party of men arrested on its premises during a radical gathering in September 1885.

It was a powder-keg situation prior to the murders. The Ripper just provided the spark.

What is The Golden Ladder?

It goes without saying that that the staging of The Golden Ladder couldn’t have been better timed given the ongoing concerns over the moral condition of Whitechapel. But what is the Golden Ladder exactly?

It turns out that the ‘Golden Ladder’ is an old meditation on charity attributed to the Hebrew Scholar, Maimonides. There are seven steps of charity, the first relating to anonymity and the last being to give ‘unwillingly’ (sacrifice?) The last level is to preclude charity by preventing poverty.

In her autobiography, Take it It For A Fact, Charles’ daughter Ada Reeve, discusses a poem her father had written some years after the Whitechapel Murders. The two-verse poem, also entitled The Golden Ladder, blames public and police apathy for the murders. The country rings with ‘shame’. For Reeve, serious and lasting reform clearly lay in preventing such horrors. Reeve’s recommendation? Put more police on the beat; place two where they place one.

Reeve, the ‘gifted stock actor of Mile End’ died at the age of 63 in November 1901 (The Era 01 December 1906, p.22) *.

* In a peculiar twist it appears that Harry Reeve’s grandfather, John Isaacs lived practically back to back with the great grandfather of Labour Leader Jeremy Corbyn in Norwich according to the 1861 Census. They lived within 200 yards of each other in the St Savior/St Mary’s Plain district of Norwich and both were Master Tailors and hatmakers. Willaim Arthur Corbyn (b.1846) lived on Duke Street with his Uncle Hartwell (b.1817), whilst John Isaac (b.1818) lived on Magdalen Street. Their local pub was called the Garibaldi Tavern on Duke Street, named after the Revolutionary Italian Giuseppe Garibaldi, popular among the radical Liberals and nonconformists (religious dissenters) of Norwich. Corbyn’s family were prominent Quakers (religious dissenters) in the area.Local MP Jeremiah Colman and nonconformity leader, J.H Tillett were the men responsible for inviting Garibaldi to Norwich during his visit to England in 1864. The visit was solicited by Colamn and Tillet’s friends Washington Wilks and George Holyoake at Garibaldi’s London Committee — the headquarters of the Italian leader’s ‘British Red Army’ (volunteer army). In another bizarre parallel it transpires that George Holyoake was the Uncle and guardian of Etaples Soldier’s Champion, Horatio Bottomley. Wilks died suddenly just weeks after organizing Garibaldi’s visit in June 1864. Garibaldi’s UK visit was cut short and his Norwich trip cancelled. The Tsarist spy and agent provocateur, Samuel Tragheim also lived in Norwich at this time (he owned the Golden Wheat Sheaf public house on Stephen Street)

* Another man who featured prominently in the Jack the Ripper story was East End landlord, ‘John ‘Jack’ McCarthy, born in Dieppe, France in 1849 and of Irish heritage. He was the landlord of victim Mary Jane Kelly and several other women who featured in the Ripper story. Kelly’s mutilated remains were found at McCarthy’s 5 Mitre Square property in Aldgate. Curiously John McCarthy’s 5 Mitre Square property also featured in another terrorist outrage, the Fenian Dynamite outrage of 1885, when American Clan Na Gael bomber, Henry Burton was arrested at this address. As Kelly’s murder happened on the first anniversary of the Bloody Sunday massacre, organized by Parnell’s Irish National Party (affiliated to the Clan Na Gael), it’s interesting that McCarthy’s parents arrived in France in 1848. This was the year of the Young Irelander Rebellion and several members of the group fled to France to escape prosecution. The group’s leader James Stephens became a founding member of the Clan Na Gael (worth noting that the Bloody Sunday demonstration was scheduled for the 9th November — Lord Mayor’s Day — and refused by Police Commission Charles Warren).

John McCarthy’s son was actor and comedian Steve McCarthy who married music hall entertainer and actress, Marie Kendall. It’s believed that Ada Reeve and Marie appeared in many Whitechapel theatre productions together. Ada also appeared alongside Steve McCarthy.

Could the Ripper Murders have Been ‘Propaganda of the Deed’?

There are several ways you could look at the Ripper murders. On the one hand they dragged the plight of London’s East End into the public domain on a blistering national scale, and on the other the murders dealt a substantial blow to working class support for the Berner Street Socialists (commonly labelled ‘nihilists’).

The Tsarist Police would have been happy with this. The Conservatives would have been happy with the this. The Liberals would have been happy with this, and the vast majority of peace-loving Orthodox Jews, keen to preserve their right to exile and the support of their British hosts would also have been happy with this.

But so too would people like Sims. The sustained interest of the National Press in the Whitechapel murders ensured discussion and debate on a daily basis. It was the ‘Grenfell’ of its day, rattling around the press columns like some grotesque political football made from the stomach sack of the victims. But as a catalyst for revolution the killings would be potent, but fraught with risks.

Did the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee organised by George Lusk and Charles Reeve at the height of the Ripper murders have anything to do with the Socialist League on Berner Street? The Political Vigilance Committee formed in Stepney some three years before certainly had. This particular Committee had been formed by the Socialist League to test the right of Police to interfere with demonstrations (Pall Mall Gazette 24 September 1885, p.10). But what if the name was an ironic swipe at the Socialist League for their failures to ensure public as opposed to political safety? Inspired by rather than in deference to?

Despite the best attempts of 21st Century television to portray Lusk as a power-hungry Socialist, Ada Reeve’s description of her father showing off her talents down the Sussex Conservative Club may indicate a more right-wing political bias. The Club at this time was managed by Sir Joseph Lyons, whose close bonds with the Pavilion Theatre practically ensured Reeve a constant supply of work. Ada describes her childhood tea-shop visits with Sir Joseph in her autobiography, Take It For A Fact. Lusk’s membership of the ‘Doric’ masonic lodge, until 1889 at least, also suggests a more Conservative bent. He was ejected from the lodge in 1889, purportedly for failing to pay his subs.

It’s interesting to note that at least one Ripperologist points their finger at the Okhrana — the Tsar’s secret police.

One thing we do know, is that exiled Russian radical, Prince Kropotkin’s successful wooing of Liberal England and his patronage at Berner Street was definitely a grave concern for the Tsarist Police at this time. Looking over the Hoover Institute’s Okhrana (Russian secret service) records I did find one entry on Ripper witness (and Arbeter Fraint editor) Jacob Rombro in Incoming Dispatches, May 7th 1891. It seems Rombro had entered the yard on Berner Street and observed Elizabeth Stride’s body. He was known as Philip Krantz and testified at Stride’s Inquest.

It’s also claimed that controversial Berner St Ripper witness Israel Schwartz appeared in French Police communications regarding Socialist rag Workers Friend (Arbeter Fraint). If you look at the Census of 1911 you will notice a Russian-Pole by the name of Israel Schwartz living at both 12 Jubilee Street and 26 Princes Square.

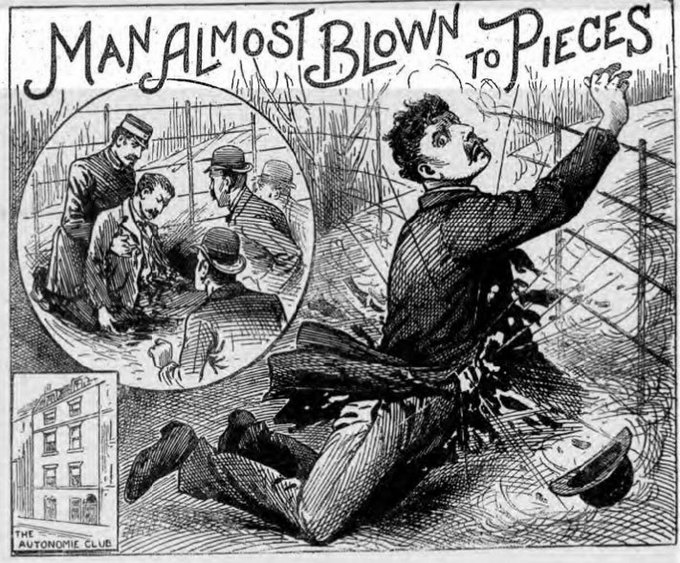

Are there clues to be found in Conrad’s Secret Agent

The inspiration for Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent was the Greenwich Observatory Bombing carried out by French Anarchist Martial Bourdin, member of the another anarchist meeting-house, the Autonomie Club on Windmill Street (Illustrated Police News February 1894). Bourdin was a contemporary of French anarchist and car thief, Jules Bonnot and has been commonly aligned with both Josef Peukert, Sergey Stepniak and Pyotr Kropotkin by historians. The actual plot of Conrad’s book, however, revolves around the attempts of Mr Vladimir of the Tsarist Russian Embassy to turn public opinion (and more specifically their wealthy Liberal sponsors) against radical Russian Exiles living in London (Michaelis/Kropotkin). For this they employed agent provocateur and pornographer (Mr Verloc) to carry out a bombing at Greenwich Observatory (1894).

Born Józef Konrad Korzeniowski into a family of nobles in the Ukraine in 1857, Joseph Conrad rewrote and published the Secret Agent in full in 1907. The novel’s publication came shortly after the 5th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. It was clearly a cautionary measure. The event had been held in London and had been attended by Lenin and Trotsky.

Reports of this period (1886-89) suggest that certain quarters of civil (and Conservative) society were showing increasing concern at the support Kropotkin and the Russian, Polish and Latvian exiles were receiving in their stand against the Tsarist regime in Russia. The Tsarist regime in Russia must have been equally concerned. Demonizing the Russian emigres in the eyes of the British Public would starve the radicals of the oxygen and resources they needed.

A plot on the Tsar’s life being hatched by ‘Nihilists’ in London in March 1887 had added some degree of urgency; The Times reporting that the “recent plot was known here and had the sanction of leading Nihilists in London” (Irvine Times 25 March 1887, p.2/The Times 16 March 1887, p.5)

The arrival of ‘nihilist revolutionary’ Prince Kropotkin in London in 1886, and Sergey Stepniak, the alleged assassin of Tsarist Police chief, General Nikolai Mezentso in July 1884, had already accelerated and amplified concern about the Nihilists. Conrad’s character, Michaelis was clearly based on Kropotkin and his wealthy benefactress may have taken inspiration from fellow Relief of Russian Exiles Club member, Lady Arthur Cecil (private secretary to Queen Victoria). By the time of the first Whitechapel murder in April 1888 (Emma Elizabeth Smith, 18 George Street, Spitalfields), Kropotkin had begun to make serious inroads with the leading London Socialists and patrons of the suffrage industry. Tellingly perhaps, the press archives for 1888 show more entries on Kropotkin than at any other time during his early British career, with March and April 1888 exceeding all other months that year.

In the first few days of September 1888, a further ‘Nihilist’ plot to kill the Tsar had been uncovered. It was followed by a spate of grisly Nihilist murders. Demands for the extradition for the group living in London under British protection had been served by the Russians as far back as March 1880, shortly before the assassination of Alexander II (Liverpool Echo, 11 March 1880, p.4). A similar treaty had been proposed by the US Secretary of State, Thomas F. Bayard in April 1887, the year prior to the Ripper murders. When Stepniak, editor of Free Russia, learned that the Americans were now prepared to extradite revolutionaries, he wrote of his surprise at how ‘liberty loving citizens of America could give moral sanction to the despotic government of Russia’ (Globe, May 21, 1887). The treaty was eventually ratified by America in 1893 with an amendment that persons guilty of attempts to assassinate the Tsar or a member of the Imperial Family should be extradited “regardless of their motives” (The Times, 08 February 1893). The British Home Office had been under enormous pressure to offer the same amendment.

Within two years of the murders at Berner Street, a senior figure within Russia’s Secret Police, General Mikhail Seliverstoff was murdered by Nihilists in France (London Daily News 25 November 1890, p.6). The murderer was a London-based refugee of Russian-Polish origin by the name of Stanlislaw Padlewski. Pyotr Rachkovsky, Chief of the Okhrana who had been in France since 1885, continued to ramp up the pressure on Britain to deal with these undesirables. Creating fear and distrust was his specialty.

Why was Revolutionary Socialism flourishing in England? Was it because the Police were too ill-equipped to deal with it? Too apathetic to deal with it? Or was it because Special Branch had decided that it was better to have their enemies move around and operate in a place they could observe them, rather than to push them still further underground? All these possibilities are explored at length in Conrad’s novel.

Four years prior to the Ripper Murders, the new Russian Consul General, Vladimir Weletsky, the basis for Conrad’s Mr Vladimir, arrived in London. His arrival and activities were the source of constant speculation. In his book, Conrad implied that Weletsky had German connections. Was there doubt among insiders regarding Weletsky’s loyalties to the Tsar? Conrad is believed to have been introduced to Weletsky at the Russian Embassy on becoming a British subject in 1886. As patron of the Society of Friends of Foreigners in Distress his contact with exiles would have been a close one.

The point that I am making is that the scope for espionage and counter-espionage, deed and counter-deed, rumour and counter-rumour, was considerable during this period, and there is every reason to think, given the shady territories of his backstory, that Conrad had based his book on experience and not conjecture. Perhaps Conrad knew something we didn’t.

The Socialists at the Berner Street Club weren’t allowed to fade into obscurity. Shortly after a rally organised by Prince Kropotkin at the Club in January 1889, the two men who had found the Ripper’s victim in the yard, Isaac Kozebrodsky and Louis Diemchutz, were arrested for assault. The assault took place during a demonstration organised by Social Democratic Federation member, Lewis Lyons, whose friend Ben Tillett would later attend the funeral of Dick Burge (London Evening Standard 26 April 1889, p.2).

Some years later, when Churchill’s not-so secret war with the Bolsheviks had entered a critical stage, the Conservative press resorted to the oft-used trick of conflating the Russian ‘menace’ with Russian Jews in the East End of London. And quite predictably it also led to the resurrection of a Jewish Jack the Ripper (April-Sept 1919). The man who oiled the narrative was Sergeant Stephen White, whose reminiscences about the Ripper were weaved creatively with the threat of the ‘anarchists’.

Ada Reeve

The daughter of Charles Reeve and the cousin of Harry Reeve was music hall actress, Ada Reeve. Curiously, during the course of the war Ada took on the moniker ‘Anzac Ada — Soldier’s Friend’ on account of her support of the Australian and New Zealand troops stationed in the UK at the time.

The generally accepted explanation for her support is that she felt sorry for the Australian and New Zealand soldiers suffering from their injuries in a hospital ward far from friends and relatives. She responded to their plight by inviting small, regular batches of convalescent Anzacs to her Malta Cottage in Norton in the Isle of Wight. Here, the men could recuperate for two or three weeks before going back to the front or sailing home.

According to Martina Lipton, Ada’s decision to focus her philanthropic work on the Anzacs, took shape during a tour of Australia and New

Zealand where she used her celebrity appeal to raise funds for the Anzac Club and Buffet for Australian and New Zealand soldiers on leave in London. Significantly perhaps, the desertion rate among the Anzac Forces was four times higher than other Dominion Divisions (Tactical Agency in War Work, Martina Lipton).

Ada appeared to be doing what many music hall stars were doing during this period; serving Britain and the Empire as propaganda agents, fundraisers and recruitment officers. Music Halls and Theatres had in fact become very capable recruitment sites.

Given that the Etaples Mutiny was started by New Zealand troops, it seems a remarkable irony that cousin Harry should have been handed one of their revolvers to shoot dead Corporal Wood.

All It Needed Was A Spark

James Cullen, sentenced to one years’ hard labour for his role in the Etaples Mutiny, was possibly the first to name Reeve as the Red Cap who triggered the mutiny. He didn’t make it obvious, of course, but his description of sharing a cell with a “famous boxer … then holder of the Lonsdale Belt” left little to the imagination.

But it’s something else that Cullen says that makes me wonder if the camp disturbances could in any way have been deliberately coordinated.

Cullen alleges that immediately prior to the mutiny, a contingent of anarchists within the ranks were distributing anti-war leaflets of a ‘most inflammatory nature’. The leaflets were asking troops to ground arm and stop the war, telling them to follow the example of their Russian brothers and refuse to shoot the enemy. It also told them to let the capitalists ‘fight their own bloody war’. Cullen also claims that the anarchists knew camp tensions were running high. It was a powder-keg situation and things were ready to blow. Troop anger at conditions was ‘at fever-pitch’. All it needed, Cullen says, ‘was a spark to cause a first-rate explosion’. That spark came, he says Corporal Harry Reeve shot Gordon Highlander, Corporal Wood. After the shooting Cullen says he was approached by a ‘prominent Communist agitator’ to further amplify disorder among the troops. The soldier told them he would do everything he could to get the troops to mutiny and a small council of action was set-up to cause a ‘general rising’ (Glasgow Weekly Record, February 19th 1927, p.4 ).

Cullen’s service records support much of what he says. He was sentenced to one year’s detention for mutiny, and it’s curious to note that on being demobilized in 1919, he became a founding member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, whose rank and file members were fairly unevenly distributed between Whitechapel and Glasgow. More of Cullen’s story can be found here.

In view of both his turbulent Whitechapel background, the proximity of his Uncle to the anarchist tensions of the Ripper period, and the Bolshevik contingent alluded to to by mutineer James Cullen, it begs the question: was Private Harry Reeve used as an agent provocateur by parties determined to stir up trouble in one of the most notorious wartime bases?

James Cullen’s assurances that Bolsheviks were exploiting the camp riot makes Reeve’s actions all the more timely. Bolsheviks knew that the soldiers in France were in ‘no very nice’ mood and that tensions were at ‘fever pitch’. It needed only ‘a spark to cause a first rate explosion’.

The very same phrase, had been used Don’t Shoot publisher, Guy Bowman and Dick Burge associate, Ben Tillett. The ‘discontent of the people was profound’ Bowman had written, ‘and the fire of their revenge is smouldering; it needs but a little spark to set it aflame’ (Justice 29 September 1906, p.3).

That Burge and Harry Reeve were working so closely together at this time, and that Tillett’s friend, the former Revolutionary Socialist Victor Grayson should arrive in the camp on the very day the Mutiny kicked-off suggests some unseen forces may have been at work.

All it needed was a spark. Could the spark have been provided by East End boxer and recently enlisted Red Cap, Harry Reeve?

Incidentally, Edwin T. Woodhall, the man who famously tracked down Percy Toplis, also got involved with film productions in Germany after the war. Woodhall was also one of the first Ripperologists (see: Jack the Ripper or When London Walked in Terror, Edwin T. Woodhall, 1937). As you might expect, much of his work on the Ripper case was rooted in Jewish-Bolshevist propaganda. As a detective with the Political Branch of Scotland Yard his work had also brought him into contact with the Nihilist movement of Whitechapel and he boasted of several encounters with Kropotkin. You can read all about his adventures in his memoirs, Detective and Secret Service Days and Secrets of Scotland Yard and in this separate post.

Lady Angela Forbes

In her memoirs, Memories and Base Details (1921), Etaples Canteen organizer, Lady Angela Forbes describes her efforts to have a large camp boxing hall erected for the benefit of the troops. She was assisted in her pursuits by her lover Lord Wemyss, treasurer of her canteen business, British Soldiers Buffets, and close friend of National Sporting Club founder, the 5th Earl of Lonsdale. All three were regular features in the fashionable hunts and shooting parties across Britain, and all of them keen sporting enthusiasts (Memories and Base Details, p.72,74,82,90,91,111). Forbes claims that no other spot in the camp was more popular than the large outdoor ring she had built, and that the roofs of the huts were treated as if they were a grandstand. Wemyss even championed Forbes’ boxing and sporting achievements during a debate at the House of Lords about the closure of the canteens in the February following the Mutiny (House of Lords, Lady Angela Forbes Canteen, 05 February 1918, vol 28 cc380-9)

Given his profile and relationship with Burge and the National Sporting Club, and given he was the current holder of the Club’s much coveted Lonsdale Belt, it seems reasonable to assume that Forbes and Wemyss had a hand in the transfer of Harry Reeve from the 4/10th Middlesex Regiment to the Military Police at Etaples.

Such a transfer would effectively keep him away from the front line, help him stay in shape but still have him doing his bit to boost morale with regular bouts at the camp. Everyone was a winner. Including the camp bookies — the Officers.

Both Forbes, Burge and the British Army had come to recognize the huge demand for ‘khaki-clad’ boxers. With the cooperation and support of the War Office, Burge had already set about organizing matinee matches under the auspices of the National Sporting Club back home as a morale booster. The NSC had been earning reputation and reach of boxing during World War I, working with various regiments to lay on training and tournaments for the British and French armed forces (Daily Mirror 26 February 1917,p.15)

If you happened to watch The Monocled Mutineer back in the eighties, you’ll know that much was made of the closure of Lady Forbes’ canteens. Certainly the authorities were concerned, a concern that was no doubt amplified by the unauthorized account of the mutiny she published in her memoirs in 1921. Her decision to open the canteens in the first place had not been a popular one, and were most likely politically motivated, with Lloyd George’s government and the Ministry of Food becoming increasingly vilified for failing to feed to the troops. In the words of the man who first told the world of the mutiny; the men ‘were being fed like whippets’ (Workers Dreadnought, November 3rd 1917, p.1).

Why her canteens were shut was never made entirely clear, and there are conflicting accounts in the archives. The House of Lords debate on the closure the following February saw Churchill, then War Secretary defending his description of Lady Forbes as little more than a ‘camp follower’. There were sleazy connotations to this phrase, and sure enough the following June, an account was heard in court that things of an improper nature were being carried out in Forbes’ huts at the base (Birmingham Daily Gazette 28 June 1918, p.3).

Churchill, however, did his level best to argue that the canteen’s closure was down to the needs of centralizing all huts in the military districts in the interests of military discipline (Coventry Evening Telegraph 06 February 1918, p.4).

Whether the indiscipline of the troops at Etaples the previous year had had an impact on that decision is not known.

Hugh Lowther, 5th Earl of Lonsdale had married Lady Grace Cecilie Gordon, third daughter of Charles Gordon, 10th Marquess of Huntly in Aberdeenshire. The Forbes, also of Aberdeesnhire, were the ‘castle next door’ so to speak. Lord Lonsdale and Lady Angela Forbes had been well acquainted for some years. Even the Minister of National Service was to take a special interest in the boxing exhibitions given at Burge’s Ring at Blackfriars Road. In the Myers Divorce Scandal that followed in June it was alleged by Mrs Myers she had to leave her work at Forbe’s huts because it had such a bad reputation. She describes it as ‘a thousand times worse than the Cranhams’ – whose house was being used for swinging activities. Curiously, Lady Angela’s sister was Sybil Fane, Countess of Westmorland, the region in which The Monocled Mutineer was ambushed.

Opinion

Thomson’s Base Camp diary records that the Police had already released Gunner Healy by the time that Reeve had fired into the crowd. This is a major discrepancy in the narrative. The Commissioned Officer, S.J.C.R writing of the events in the Manchester Guardian in February 1930 says that Healy had made a ‘dash for liberty’ and that Reeve had shot at him as he escaped, accidentally killing Corporal Wood. Thomson’s official Base Camp diary contradicts this. The Brigadier General records that police had received warning from a Corporal of No.27 Infantry Base Depot that New Zealand troops were planning an assault on the compound after the arrest of another soldier, earlier in the day. Gunner Healy was arrested shortly after this warning was served and then immediately released in an attempt to avert any such raid on the compound. A New Zealand representative is said to have gone to the police guard room and demanded Gunner Healy’s release on behalf of the troops planning the raid. He was shown that Healy had been released and had already left the guard room.

The smart preemptive move of releasing Gunner Healy should, by rights, have averted the subsequent riot, yet despite the compliance and composure shown by the Police, the mutiny seems to have stormed ahead regardless.

Could this be an indication that the detainment of Gunner Healy had been conceived as a deliberate ploy to set in motion a chain of events that would end in a mass riot? Was this the first in series of ‘sparks’ that had failed to land on the tinder? Did it suddenly require more desperate, and more violent measures?

If Gunner Healy, arrested by Reeve, had already been released and the Police were clearly preparing to avert a crisis, then what prompted Reeve to shoot? Pure panic? Or something else?

In a peculiar twist it appears that much the same sequence of events had ignited the mutiny on the Russian Battleship Potemkin during the revolution of 1905. In this equally notorious episode, the ship’s second in command, Ippolit Giliarovsky snatched a gun from hands of a threatening crew member and shot dead a mutiny leader. At that moment all hell broke loose and within minutes, several officers were dead. It was, in the words of Etaples Mutineer James Cullen, all the spark that was needed to ignite a first-rate explosion. And Cullen, incidentally makes some thinly veiled allusions to have actually BEEN in Russia during this period in his four-part serial in the Glasgow Weekly Herald (February -March 1927) .

There’s certainly no shortage of coincidences, that’s for sure. East End Liberal and soldier’s champion, Horatio Bottomley just happening to be at Etaples at the time the Mutiny took place, Winston Churchill just happening to be with General Haig in France when Haig first learns and responds to the Etaples Mutiny, Reeve’s promoter Dick Burge being transferred to the Military Police at the time of the Etaples Mutiny, Reeve being transferred to the Military Police shortly before the Etaples Mutiny, Don’t Shoot Revolutionary Socialist Ben Tillett being at Dick Burge’s funeral the following March, Ben Tillett’s friend Victor Grayson arriving with his New Zealand regiment at Etaples on the day that the mutiny starts (and arriving in the very section in which it foments), Reeve’s Uncle Charles featuring in the Ripper adventures, his actress cousin Ada hosting New Zealand troops at her home, Harry’s first movie being produced by the Secret Service’s production company. I could go on.

But if the mutiny had been planned and coordinated some weeks or even months beforehand, which side was responsible? Was it Anti-Bolsheviks like Bottomley and Churchill in a bold and risky attempt to escalate support in Parliament to tackle Bolshevism back at home? A move by committed patriots to secure better conditions for troops and avert the mass desertions they’d seen in the French and Russian armies? Or Revolutionary Anarchists and Socialists trying to imitate their Russian comrades? Or could it have been a plot by German spies to undermine the British war effort? The options are as deep as they are wide and go rattling around with the same intense paranoia and uncertainty that came to define the period, and our often hysterical grasp of it.

One thing I haven’t been able to clear up is whether Horatio Bottomley’s partner in Hansard Publishing Union, Sir Henry Isaacs (b.1830), serving as Mayor of London in the two years following the Ripper murders, was in any way related to Harry Reeve (born Henry Isaacs)? Both families were from Whitechapel — Sir Henry’s from a family of fruit merchants at 19 Mitre Street in the Aldgate district of the East End, where the body of Catherine Eddowes was found. Despite living in Norwich, Reeve’s grandfather, John Isaacs (b.1815) was similarly born in this area. Interestingly, Sir Henry’s great Uncle was another champion British boxer — Daniel Mendoza — and one of his closest political allies and friends was the patron of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, Sir Samuel Montagu. That Harry’s grandfather named his first-born son Henry, certainly adds to the possibility.

Was the dumping of Eddowe’s body in Mitre Square an attempt to smear or derail the September-November 1888 candidacy of Sir Henry as Mayor? There were other Jewish candidates of course, Whitechapel Conservative (and Foreign Office regular), Lieutenant Colonel Phineas Cowan among them, but none were quite so radical as Sir Henry. The fact that his partner Bottomley had been initiated into the Polish National Lodge (No. 778) a few years previously certainly can’t have improved his standing as it had been set up in London by anti-Tsarist Russian and Polish exiles. Julian Konstanty Ordon who had taken part in the anti-Tsarist November Uprising, was a founding member, as were Lord Dudley Stuart and Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski). Furthermore, the concerns of the Lodge were inextricably wound-up in the affairs of the Polish Central Committee (the Polish Revolutionary Commune) in London, who had the cooperation and the patronage of luminary Russian radicals Alexander Herzen and Prince Kropotkin.

It may also be worth noting that The International Working Men’s Club on Berner Street, where Elizabeth Stride’s body was found, had been founded in honour of Poland’s January Uprising. Sir Henry was also directly up against Samuel Montagu’s second cousin Mr Cowan, placing him very much in the orbit of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, at this time chaired by Montagu.

Was it just a coincidence that the frequency and brutality of the Whitechapel Murders coincided with the announcement that Sir Henry would be standing as candidate for London Mayor? Having such a respected supporter of the Revolutionary Commune play an increasingly central role in the civil affairs of the capital would have been a hugely boost for the Polish cause. Sadly, despite a strong campaign, Sir Henry lost to Sir James Whitehead. But it wasn’t before the Ripper chose one final victim. On November 9th 1888, the body of last known Ripper victim, Mary Jane Kelly was found in Dorset Street. It was the day of the Lord Mayor’s show — the day on which Whitehead was sworn in as Mayor and the hopes and dreams of East End reformer, Sir Henry were well and truly terminated.

Fortunately the Police had been swift to deal with some fairly crude attempts to conflate the Ripper Murders with Jewish radicals, the quick-thinking Detective Halse rubbing out the provocative message, “Jews are the men that will not be blamed for nothing” written in chalk above the wall near to where Eddowes body had been found (Globe, 11 October 1888). It’s entirely likely that measures to deal with propaganda had been put in place earlier in September when the Tsarist Secret Police had begun circulating an almost certainly fictitious story among press journalists that Jewish Anarchist, Nikolay Vasilyev — rumoured to have committed similar atrocities in Paris — was responsible for the Whitechapel crimes (Dundee Courier 29 November 1888 p.2/Liverpool Echo 13 September 1889 p.2). It’s possible that the feeling among senior officers of The Met like Sir Charles Warren (who resigned on the eve of the last murder) was that the solution to the Whitechapel Murders would most likely be solved by diplomatic rather than policing channels.

Warren, who had stood as a Radical Liberal MP in Sheffield just three years previously, may have suspected it was the work of Okhrana agents, or perhaps even counter work by anarchist rivals, but due to political and diplomatic pressures, the beleaguered Commissioner may have been powerless to pursue it as a formal line of enquiry. The tensions between Warren and Conservative MP, Sir Henry Matthews of the British Home Office in the weeks leading up to his resignation had led him to conclude that whilst he had been ‘saddled with the responsibility’ of Policing he had ‘no freedom of action’ (Aberdeen Free Press 13 November 1888, p.5).

Warren’s political and policing career had taken a serious battering just twelve months before when a mass unemployed rally at Trafalgar Square — scheduled originally for November 9th — erupted in violence after a small group of radicals led by belligerents within the Socialist League clashed with Police. Over 75 people were seriously injured and Warren and the Met were harshly criticized for their heavy-handed tactics. The episode soon became known as ‘Bloody Sunday’.

In an interview with The World journal in the January before the riots, Warren clarified his belief that whilst “Socialism must be closely watched” he recognised the “wide distinction” between foreign and British “agitators” and between the “educated leaders and the “tag, rag and bob tail” rabble out to cause trouble (The World, January 1887). Was it just a coincidence that the resignation of Sir Charles arrived exactly 12-months to the day that the riots took place in Trafalgar? And was it just a coincidence that the body of Mary Jane Kelly, the Ripper’s final victim, was found on the day of the Lord Mayor’s Show — the day that the original demonstration had been scheduled to take place?

Whatever the truth of the matter, the discovery of Kelly’s body in Dorset Street was enough to scupper the plans in place for another Lord Mayor’s Day demonstration, a formidable Police presence having already been mustered to support search efforts and door-to-door enquiries.

Any action the militants may have planned that day was dealt a blow as cruel and every bit as fatal as the Ripper’s; the front page news was Jack’s.

In an interview with the New York Herald Warren confirmed that it was the ‘interference of the Home Office in the Police Department’ that was behind his decision to quit (Philadelphia Times 13 November 1888, p.1). There had been rumours of his resignation as early as September 5th.

Home and Foreign Office meddling in the investigation was clearly a mitigating factor. To have brought the culprit to justice may have required the Met and its Commissioner moving away from the State Department. As a military man, Warren had been far more accustomed to giving orders than to taking them. *

Also, what did Horatio Bottomley mean when he wrote, “I should like to tell you how a German plot to spread mutiny in a certain Reinforcement Camp was squelched”? (John Bull, October 13th, 1917). The statement was made beneath a headline that read, ‘What I Must Not Tell’ on his return to writing that October. But what credible evidence did Bottomley have that such a plot existed?

Did this provide a clue to the most likely explanation yet? That Churchill and the military had been warned of such a plot and had prepared their response beforehand? Having Bottomley in France and additional muscle like Reeve secreted around the base may be viewed as attempts at containment. Churchill, wasn’t one to sit around idly waiting for things to happen, so was this why he was in France? To monitor and respond to developments first-hand? Whilst Haig offers no explanation for Churchill’s visit on the Wednesday of the riots (September 12th), it’s curious to see Bottomley arriving for lunch the very same day (Douglas Haig Diaries and Letters 1914 1918, Wednesday September 12th).

Bottomley had been accompanied on his trip by photographer, Lieutenant Ernest Brooks working in an official capacity for the British War Office. But Brook’s initial assignment had been with Churchill (himself a former journalist) at the Admiralty. Haig’s diary suggests Churchill’s visit was something of a rare event, and it’s a matter of public record that Haig and Churchill’s relationship was antagonistic at best. Haig’s entry for September 12th concludes with a description of Churchill running down the hill “in such a hurry that he forgot his hat” when the shelling started. In view of Brooks’ presence there that week, it seems safe to assume that Bottomley’s trip had been organised by the Ministry of Information.

Had Churchill and Bottomley travelled from England together?

Playwright and journalist, George R. Sims who had written The Golden Ladder play that Harry’s Uncle Charles Reeve was acting in on the night of the Eddowes and the Stride murders, made his own views known on the German and Tsarist threats just months before the arrival of Bottomley in France. Writing in the Referee, he says, “the suggestion that the Czar and the pro-German Czaritza should make their home in England has not been received with favour by the English people. We do not want the centre of the pro-German plot transferred from Petrograd to London. We have more German personalities here than is consistent with the safety of the Realm” (The Referee, April 1917). Bottomley and Sims were, incidentally, both regular speakers at trade dinners organised by the Kinematograph Defence League.

Answers to any of these questions are unlikely to be forthcoming. The report by the Haig Board of Enquiry chaired by Asser and Thomson at the time of the Etaples Mutiny appears to have been lost. There was no release of ‘secret documents’ on its 100th Anniversary. No announcement was made in Whitehall or by the Ministry of Defence. There was no dramatic break in the clouds and Percy Toplis tumbling out of it with an unredacted copy of his Monocled Memoirs. In fact, much of it is lost to history. And indeed, to memory.

What I think we can safely say it was not, was some secret coalition of Freemasons and Jews to take alter the shape of the war. Any attempt to aggregate such theories tends to collapse in a heap of misconceptions. If charity is an evil, or the celebration of good causes a malevolent force then the likes of Sir Henry Montagu and Sir Walter de Frece would indeed be national poison.

And it’s for this reason that I’ll let mouthy Etaples Canteen legend, Lady Angela Forbes have the last word:

If I were a Prime Minister I should promise nothing, but I should spend my time in devising means to reduce this strangling taxation and unemployment, and if I succeeded even a little in that direction my tenure of office would be secure. I should reduce Government staffs to a practical minimum, and I should order other people about not be twisted round other people’s fingers. I think I should know that Kharkow was not a general, even though I could not put my finger exactly on its situation on the map. I should bind our colonies to us with bars of steel ; I should make the firmest alliance possible with France ; I should fight alien labour to the death ; I should squash the Jewish invasion by every means in my power, even if it meant having fewer new frocks. But then I never shall be Prime Minister.

Lady Angela Forbes, Memories and Base Details, 1921, Hutchinson & Co

* The murder of Catherine Eddowes in the street where Sir Henry was born, and within days of Mayoral elections in which Sir Henry featured, can hardly be a coincidence. His friendship and business relationship with local radical, Horatio Bottomley, recently initiated into the squarely revolutionary Polish National Lodge, would have made his candidacy all the more controversial. The following year Bottomley, Isaacs and Charles Kegan Paul were making Austrian Conservatives uneasy by launching Anglo-Austrian Printing and Publishing Company, probably on issues relating to Austrian Poland (Galicia). The various conflicts and tensions arising from Panslavism and Polish Independence were now being actively fought on British Soil. As the Mayoral elections drew closer, the Tsarist Police tried to persuade Special Branch that Paris-based Russian radicals were colluding with the Irish Feinians, and it’s certainly interesting to note that several of the Ripper victims had links to both France and Ireland. Was there scope among the women for suspected spying activities? Curiously the man largely responsible for bringing about the resignation of Police Commissioner Charles Warren on the eve of the last Ripper murder, was the newly elected Conservative, Viscount Henry Matthews who also responsible for the controversial hanging of Berner Street Jew, Israel Lipski the year prior to the Ripper murders.

Further reading:

Etaples Base Camp Diaries, National Archives, WO-95-4027-5

Tactical Agency in War Work: ‘Anzac Ada’ Reeve, the Soldiers’ Friend‘, Martina Lipton

Memories and Base Camp Details, Lady Angela Forbes, London Hutchinson, 1921

The Mutiny at Etaples, The Manchester Guardian, February 13 1930.

To The Editor, A.B Newland, Otago Daily Times, Issue 18496, 6 March 1922

Detective and Secret Service Days, Edwin T. Woodhall, Jarrolds, London, 1929 (description of the Etaples Mutiny, its aftermath, his time with the Military Police and his encounter with, Monocled Mutineer Percy Toplis)

Vera Brittain, Testament of Youth, Victor Gollancz, 1933 (Death of Officer in Etaples Bull Ring)

Whitechapel Candidature of Mr Montagu, Tower Hamlets Independent and East End Local Advertiser 03 July 1886, p. 7

The Monocled Mutineer, John Fairley and William Allison, Souvenir Press, 2015

Infamy and Redemption: The Strange Tale of Former British Boxing Champion Dick Burge, Arne K. Lang, October 7, 2018.

Lord Reading: The Life of Rufus Isaacs, First Marquess of Reading

Front Cover Harford Montgomery Hyde (Sir Henry Isaacs and 19 Mitre Street)

Texture of Politics: London’s Anarchist Clubs, 1884 – 1914, Jonathan Moses, Royal Holloway University London

Anglo-Polish Masonica, Maria Danilewicz, The Polish Review, Vol. 15, No. 2, 1970, pp. 5-42 (guide to the Polish National Lodge and its founders)

Tweets by repeat_the_past

Hi,

I just came across this article for the first time and knew nothing of it despite Harry Reeve being my great grandad. My grandad was Harry’s youngest son and while he told me of his boxing accolades he never mentioned this story (although maybe I can understand why). I just wanted to say thank you for taking the time to research his life so thoroughly and for producing this extremely insightful read.

Thanks for the thumbs-up. Glad you enjoyed it. They had to fight tooth and nail to get ahead in those days. He was still quite young when all this took place. Can’t blame him for moving on and putting it all behind him.