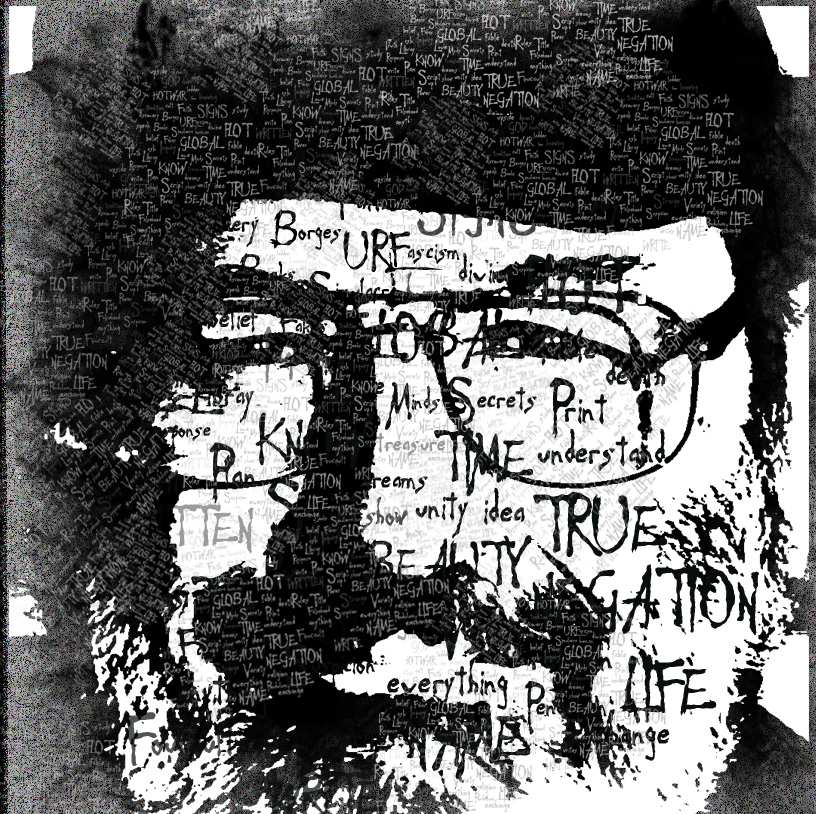

He provided signposts in a world of infinite junctions, a road map in a world of infinite signs.

Discovering Umberto Eco at University was a bit like discovering sex. During the long bleak months of winter 1990 I’d read his novel, The Name of The Rose back to back with Travels in Hyperreality — a witty collection of articles and essays that extended and clarified the previously impenetrable theories of mavericks like Albert Borgmann, Jean Baudrillard and Jacques Derrida. All of a sudden reality became something you could slice through like a layer-cake. All the various archaeological methods that we’d been sheepishly applying to text were now beginning to expose the tantalizing bones and fragments that made up the world around us. Suddenly the world was full of signs. Suddenly everything could have a meaning — and it no longer mattered whether it was intentional or not. Disneyland, Madame Tussauds, Jurassic Park, the Mona Lisa — all could be subjected to the same rigorous analysis as Ulysses or Paradise Lost. It was a low-brow-high-brow phenomenon and it spread through my world like Beatlemania. And in my imagination at least, Umberto Eco took on the role of road manager.

In the context of more traditional approaches to study, Eco was forbidden fruit. It was no longer a case of discussing what the author of a book intended to say, but recognizing that any intention the author may have had was being routinely subverted, re-routed and re-drafted by the rest of us. It was regime-change at a textual level. Just like me and my spotty housemates now had a life outside of our parents’ homes, the novel or the poem had a life outside of the author. Like a teenager in the grip of some wild, hormonal impulse we (and the book) could indulge in hour after hour of furtive sign-play, experiment with various deconstructive processes and try ‘the joy of text’ in as many positions as possible. The fusty old traditionalists that made up the rank and file on the campus considered our violent interrogation of the text a serious violation; the walls of their most cherished beliefs were in danger of being riddled with bullet holes. Or stains at the very least.

We didn’t see it that way.

To us they weren’t bullet holes, they were peep-holes onto the most fantastic possibilities. When the sign floated away from the signifier and jouissance dissolved meaning there was no sense of grief or loss among us scruffy, unruly libertines. There were secrets to be explored, mysteries to unravel. In the spirit of classic sleuthing we explored the stairwells, attics and alleyways of literary intent. And whilst bodies were seldom uncovered we did stumble across the occasional spent cartridge and chalk outline from time to time.

No, these weren’t really bullet holes at all; these were stars being punched into the blackest of nights, tiny bright sparks of inspiration and imagination. It was like the sky had been peppered with clues.

Books were never meant to get smaller the more you read them. They weren’t a resource that you were ever meant to deplete. With Eco they just got bigger. With Eco, books just got better.

A good book is more intelligent than its author. It can say things that the writer is not aware of — Umberto Eco

As copies of The Open Work began to exchange hands (almost) as enthusiastically as Nirvana’s ‘Nevermind’ album, the desire to master or dominate a text lessened with each passing term. Now that the reader had a role in the book’s production every bit as vital as that of the author, books were becoming irreducible. The meaning of a book became a job-share opportunity. The author wasn’t so much dead as reborn in the reader’s image.

Where the traditionalists saw breaks, we saw continuity. Where they saw a plan, we just saw sparks and flashes. They were dumbfounded by truth, earthbound by absolutes, rooted in certainties and trapped like sticks in the mud with things that were either fixed, partly fixed, or possessed some kind of hard, non-negotiable centre. We, on the otherhand, as raw and unknowing as we were, broke well and truly free of orbit with every careless choice we made and every word we jiggled loose from its original context. As sure as the head on our foaming pint of grossly over-subsidized beer came loose from the pale yellow liquid beneath it, we were free from the tyranny of intention that the totalitarian Formalist system had distributed like contraceptives among us. They saw the crescent. We saw the whole of the moon. Contenting ourselves with syntax and grammar in the pursuit of the author’s meaning was like contenting ourselves with a bit of kissing and touching when what we wanted was full-blown sex.

The various new seams and layers we were discovering within these books could now be mined with almost limitless aggression, kissed with almost limitless love. Language now had a life-cycle that was as adaptable and provisional as any living thing. And it was every bit as tantalizing and elusive as the girls we encountered down the Student Union bar. The meaning of the author’s work was encoded in a series of messages relayed to us by signs but it was our own little Enigma machines that did all the serious decoding and ensured they had a life thereafter. Meaning was derived by negotiation and words became all the more exciting when negotiations failed. Like most of the fleeting pleasures we enjoyed during those furtive days on campus, our appreciation of a work was down to a seminal exchange of fluids. With books it was just a little more regular, and lasted more than just a few minutes.

With the publication of his Eternal Fascism a few years later, Eco even managed to traffic us a 14-point challenge to radical authoritarianism that was as easy to assemble and as lightning fast to load as a Glock 23 handgun. And boy did that come in useful when you were refused entry by some burly knucklehead bouncer down at the City Hall. Words no longer presented walls but escape routes. They were the serrated edge of the file we had hidden inside the cake. In the event of a scuffle or confrontation we tossed them like hand-grenades and made a run for it, stopping only for a bag of chips or a ‘Nibbles’ Pizza along the way.

“Let it be clear, my boy”, he explained, all formality now gone, “that what I produce are not forgeries but new copies of genuine documents which have been lost, or, by simple oversight, have never been produced, and which could and should have been produced.” — The Prague Cemetery, p.109, Umberto Eco

Prague Cemetery, published in 2010, marked a new found maturity in my reading of Eco. Things were a little different now. I was married. I had children and since September 2001, at least, there had been things hovering in my peripheral vision that were marginally more sinister than Disneyland and Tussauds — and yes, even more unsettling than girls.

In many respects the novel was Eco’s ‘Blackstar’ release. Not because it was the writer’s swansong or his beat-noir parting gift to the world, but because it drew together strands of Eternal Fascism and other bestselling offcuts like The Power of Falsehood and Fictional Protocols — essays that did their best to crash the conspiracy exchange mechanism that helped perpetuate intellectual antisemitism throughout the world. It was the literary equivalent of pulling the mask and the shirt off the emperor and marked an increasingly urgent need to uncouple radical politics from the deeply paranoid conspiracy matrix that propped it up.

In contrast to the wacky conspiracy narratives weaved in Foucault’s Pendulum which are depicted (often amusingly) as the consequence of human error, miscommunication and random text programming, the fakery that characterized Prague Cemetery was premeditated and malicious. Even today the currency and worth of anti-Semitic fictions like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is substantial. It offers life-support to everything from Islamic Fundamentalism to neo-Nazism. It’s there in the material being pushed by the Ku Klux Klan, and it’s being distributed with no less fanaticism by Louis Farrakhan’s Nation of Islam. This completely fabricated text is as critical in preserving the medieval mania of Islamic State as it the post-Nietzschean ‘mathematics’ of the Five Percent Nation.

Strangely, this was one of the very few times in his career that Eco may have come close to conceding that the intentions of the author were more wilful and controlling than those of the reader. In Eco’s estimation the intent in this particular instance was as grievous as it was relentless. It was fake Edwardian news of the most treacherous order.

The writer had once said that to survive you must tell stories, and that is essentially what these ghouls were doing here; they were snatching bodies from charnel house of text to create a lumbering patchwork monster. And it was only in unpicking these bones and rearticulating those skeletal remains that would reveal the story for what it was — a lie.

It’s just a shame that Umberto didn’t hang around long enough to see if his efforts to pull the wool from the eyes of the world’s sheep was about to pay off.

Someone once said that words were never enough. It could have been Shakespeare, or it might have been One Direction or David Cassidy, I can’t be sure (how can I be sure?). But the simple truth of the matter is this: it’s not that words are never enough, it’s that there are just never enough words, and words can never have enough meaning.

If you happen to see Eco tipping his hat, don’t read it as proof he is saying goodbye, read it as a sign that he is always arriving.

[Eco died at his home in northern Italy on Friday 19th February 2016 . He was 84.]

Alan Sargeant 2016

They say the best way to flatter a man is to quote him and the easiest way insult him, to misquote him and then steal his beer. I’m going to settle for the former:

“Nothing gives a fearful man more courage than another’s fear.”

“A good book is more intelligent than its author. It can say things that the writer is not aware of.”

“Thus I rediscovered what writers have always known (and have told us again and again): books always speak of other books, and every story tells a story that has already been told.”

“Books are not made to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry.

Ur-Fascism grows up & seeks for consensus by exploiting & exacerbating the natural fear of difference.”

“When the writer (or the artist in general) says he has worked without giving any thought to the rules of the process, he simply means he was working without realizing he knew the rules.”

“Ur-Fascism derives from individual or social frustration.”

“To people who feel deprived of a clear social identity, Ur-Fascism says that their only privilege is the most common one.”

“For Ur-Fascism there is no struggle for life but, rather, life is lived for struggle (Armageddon complex)”

“The author should die once he has finished writing. So as not to trouble the path of the text.”

“The Ur-Fascist hero craves heroic death, advertised as the best reward for a heroic life.”

other links:

UR-Fascism, Umberto Eco, The New York Review of Books, June 22, 1995

The Death of Umberto Eco – Guardian