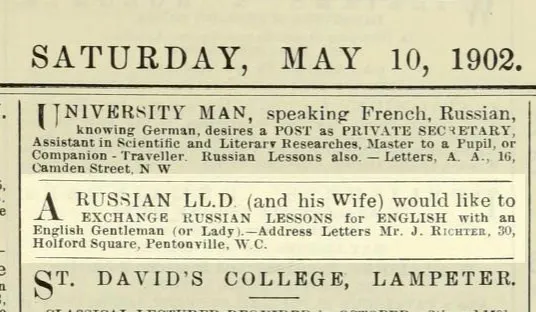

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya resided at 30 Holford Square from April 1902 until May 1903. As Bob Henderson’s seminal article, Lenin and the British Museum (Solanus, Vol 4) points out, it was from this address that Lenin, using his now customary pseudonym, Jacob Richter, first wrote to the Director of the British Museum asking permission to study in the museum library. St Pancras Station was approximately ten-minutes’ walk east of the property and Kings Cross Station was just a few minutes around the corner. According to James Maxton’s Lenin (1938) the only special advantages the house had were that it was situated ‘between the British Museum and Highgate Cemetery, where Karl Marx was buried.’

As the spies of Russia’s secret police were everywhere, it’s unlikely that Lenin took any risks, so it may be safe to assume that the house and its occupants had been screened ahead of his arrival and were part and parcel of a trusted support network. Lenin would be hosting group meetings here, so secrecy would have to be maintained. As Maxton points out, ‘the care with which Lenin concealed his identity was no mere stage-trick, but an absolutely necessary precaution for the safety of his lieutenants and followers in Russia itself.’ (Lenin, 1938, p.58). And on a salary of £6 a year, Lenin and his wife would have to live as cheaply as possible. Nadezhda Krupskaya would later recollect that it was ‘the Takhtarievs’ who fixed them up with the property (Apollinaria Alexandrovna Yakubova and her husband, Konstantin Takhtarev — Memories Of Lenin, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya, 1930).

The house’s proximity to Harry Quelch’s printing offices at 37a Clerkenwell Green meant it was ideal for managing Lenin’s Iskra newspaper. Harry Quelch, the former secretary of The London South Side Labour Protection League who stood as candidate for Labour and the Social Democratic Party in 1906, had been handed the premises by William Morris and it was from here that Quelch produced his Chants of Labour and Justice newspapers. Quelch extended the same generosity to Lenin for the purposes of managing Iskra.

There’s a possible connection between the Holford Square property and Lenin’s 1905 address, 16 Percy Circus, the family home of Philip Whitwell Wilson. Wilson, the MP for St Pancras South recalibrated Quelch’s 1909 speech, The War and Social Revolution just a few years after its debut. Wilson had provided Lenin with accommodation at Percy Circus during his 1905 visit (see The War and Social Revolution , Philip Whitwell Wilson, Fortnightly Review, Volume 22, October 1915). By 1918 the printing offices of 37 Clerkenwell Green were being used at the headquarters of Ben Tillet, Wily Thorne and James O’ Grady’s National Socialist Party.

Originally, 37 Clerkenwell Green had been home to the London Patriotic Club, one of a number of groups attempting to form alliances between the radical liberal movements demanding votes for women and those supporting Irish Home Rule. Patrons at this time included Prince Peter Kropotkin. Membership consisted of everyone from Socialists and Liberals to followers of Narodnaya Volya, the Russian Revolutionary group responsible for the murder of Tsar Alexander II.

At 30 Holford Square, Lenin would nourish and entertain a train of regular visitors including Trotsky, Plekhanov, the Takhtarevs and Novaya Zhizn editor, Maxim Litvinoff. Litvinoff remembers being taken to “two shabby little rooms … so meagerly furnished that there were not enough chairs for those present.” (Maxim Litvinoff Voll. Ii, Arthur Upham Pope, 1943). Their contact with English Socialists came primarily through the Takhtarevs. By their own admission Lenin and Krupskaya knew little about the home life of the English Social Democrats. They found them to be a reserved people “who regarded the Bohemian life of the Russian emigres with a naive perplexity.” (Memories Of Lenin, 1930). They were just as critical of the Social Democrats they found themselves lodging with. Here, according to Krupskaya, “they sampled the whole bottomless inanity of petty bourgeois life.” (Memories Of Lenin, 1930, p53). Petty or not, it didn’t stop the future Soviet leader from knitting himself and his plans into the warm fabric of bourgeois sympathies *

Samuel F. Deering & the Mysterious Fortunes of Frederick Case

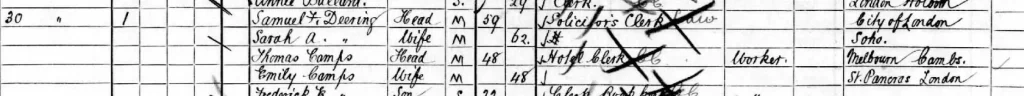

The official occupants at 30 Holford Square at the time of Lenin’s visit in 1902 were Samuel Frederick Deering, a 60-year old Solicitor’s Clerk/Civil Servant living with his wife Sarah and 48-year old Thomas Camps and his wife Emily. Deering had been brought up at 4 Sidney Square in Whitechapel, Stepney. He and his family had lived just yards from the infamous Sidney Street, scene of the revolutionary siege in 1911 (the siege took place at no.100 Sidney Street, see map below). According to Lenin and the Revolution (1947) by Christopher Hill the landlady’s name was Mrs Emma Yeo of 24 Grafton Place, whose recently deceased husband Daniel had been a ‘printing compositor’ or ‘typesetter’ (Lenin’s co-lodger in 1911, Winifred Gottschalk would use 9 Grafton Street on her marriage certificate). In fact, looking at their record in the 1901 Census it’s clear that the Yeo family were all in publishing and that their Grafton Street abode had at one time been the premises of a Swedenborgian Church (Junior Members Society).

Little is known about Deering’s earlier life. He disappears from the census of 1861 and 1871, so it may be he is the same Samuel Deering who becomes a Merchant Seaman on the ‘Kangaroo’ in 1853 and the same Samuel Frederick Deering who starts appearing at 4 Queen Street in Soho in the Westminster Rates Books (1634-1900) from 1873 onwards. At this time, 4 Queen Street were the premises of the Koppenhagen Brothers (German tobacconists/cigar importers), represented by Leon, Julius and Jacob Koppenhagen. Julius Koppenhagen subsequently partnered Whitechapel’s Joseph Gluckstein (b.1856) at the Imperial of the Imperial Tobacco Company. Joseph went on to father Sir Louis Gluckstein MP.

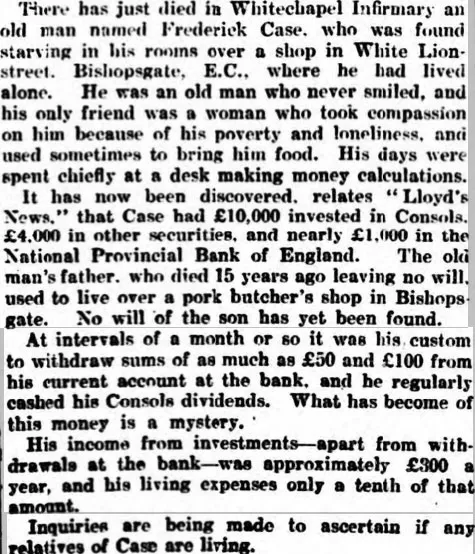

In 1916, Samuel Frederick Deering is drawn into a mysterious inheritance story featuring Whitechapel Board of Guardians and one of their patients, 79-year old Frederick Case who has died whilst in the care of their Infirmary. Here’s what we know:

- Whitechapel health visitors find Frederick Case (b.1841) starving in his room in White Lion Street, Bishopsgate. According to a report in the East London Observer of January 1916, the old man is a recluse with no family or friends to speak of. He is befriended by a lady who owns the shop downstairs and she prepares his only known meals. She claims Case’s days were spent chiefly at his desk performing monetary calculations. The old man is found to be suffering ‘mania and bronchitis’ and taken into care at Whitechapel Workhouse.

- After his death at the workhouse some weeks later, it is discovered that the ‘impoverished’ Frederick Case had over £10,000 invested in Consols, £4,000 in other securities and over £1,000 in the National Providential Bank. This amounts to nearly £890,000 in today’s money.

- It is known that he would withdraw sums of money as large as £50 and £100 at intervals each month and would regularly cash his Consols dividends. What he did with this money remained a mystery as he appeared to be living in abject poverty (£50 is about £3,000 in today’s money).

- His father William Henry Case (b.1812), the Ward Beadle of Bishopsgate, died in 1901. Frederick had left no will.

- The story goes nationwide and there is a significant volume of claims. The money is held by the trustees at the Board of Guardians.

- After a successful appeal featuring solicitors Proudfoot & Chaplin he money is eventually awarded to Samuel Frederick Deering who the Guardians believe to be a cousin of the deceased (see Public Trustee Vs Deering, 1916 C.903)

- Starting life as Oil & Colour Merchants Frederick and his father William become Rate Collectors in Bishopsgate during the mid-1880s. As Ward Beadle, his father would have been responsible for coordinating and managing local elections.

- Frederick Case’s brother William is believed to have left for South Africa some twenty years earlier.

- There are a number of years in the census in which Frederick Case cannot be accounted for.

- The women who attend his funeral are a Miss Siebert and her niece, Miss Emery & a Miss Keeler.

Recommended reading:

Conspirator: Lenin in Exile – Helen Rappaport

The Spark That Lit the Revolution – Robert Henderson

Related Articles

Lenin at Tavistock Square

Lenin at Percy Circus