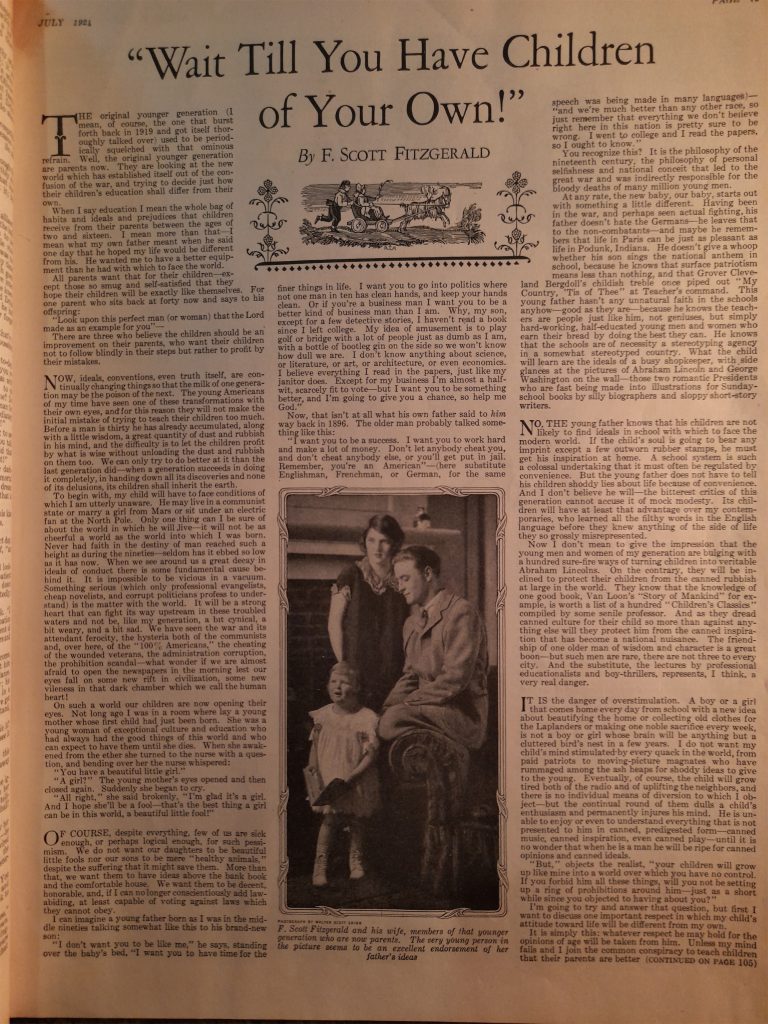

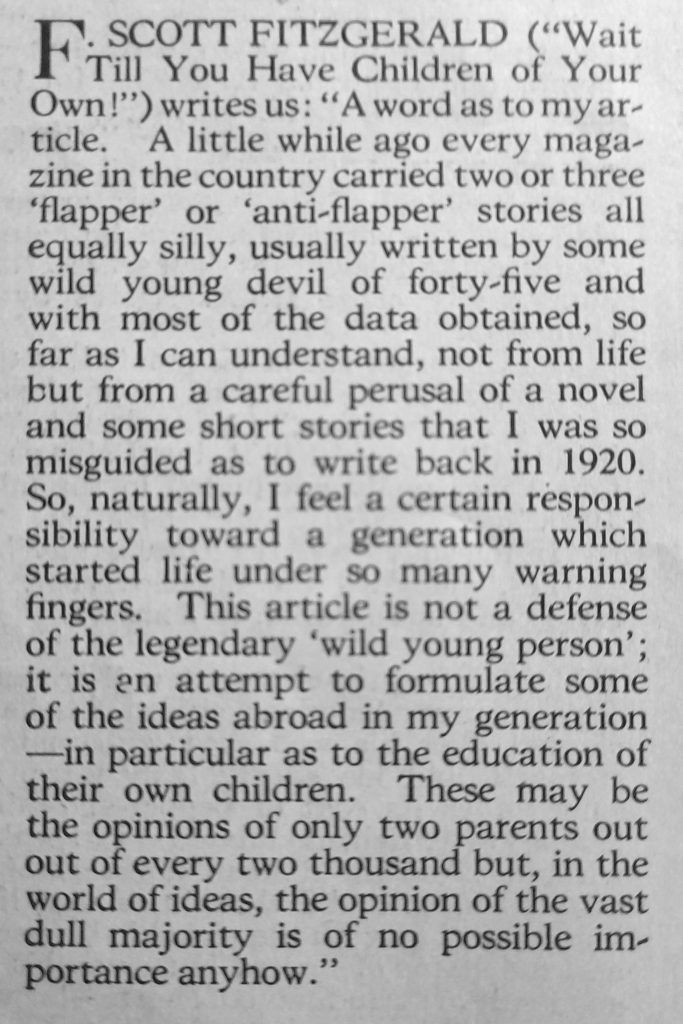

When my wife gifted me with a copy of The Woman’s Home Companion, I came across an item that hasn’t been seen for over a hundred years. It’s from the pen of F. Scott Fitzgerald and it is the brief explanation he provided for his article, ‘Wait Till You Have Children of Your Own’. The clip is taken from The Woman’s Home Companion, July 1924, Vol. LI, No.7 (‘Who’s In This Issue: Notes About Our Authors’, p.110). To the best of my knowledge, the item doesn’t feature in the Firestone archive at Princeton and I haven’t seen it referred to in any essay or biography. Scott’s article, about the education of children in 1920s America, was supported in the issue by similarly themed articles from the pen of his Great Neck neighbour General John J. Pershing (‘Peace Time Patriotism’) and Bostold Herald editor, Edward Elwell Whiting (‘Independence Day Every Day’). Scott received $900 for the article. In his ledger, Scott writes in the ‘remarks’ column of this entry, ’Partly incorporated into Gatsby’) An hour-long podcast at the bottom of this page explains how the author did this, as it goes some way beyond the inclusion of the “beautiful little fool’ quote that features here.

I’ve also included a screenshot of Whiting’s article at the bottom of this page as I feel that certain aspects of it may have inspired key images and themes that Fitzgerald went on to develop in The Great Gatsby (see the column beginning: “We have kept the goal in sight; we shall never quite reach it … beacons that beckon us on … we may never cease to stretch our hands toward them” in the context of Gatsby’s hand stretching toward the green light.)

WHO’S WHO IN THIS ISSUE: A Brief Note About Our Authors

SCOTT FITZGERALD (“Wait You Have Children of Your Own!”) writes us: “A word as to my article. A little while ago every magazine in the country carried two or three ‘flapper’ or ‘anti-flapper’ stories all equally silly, usually written by some wild young devil of forty-five and with most of the data obtained, so far as I can understand, not from life but from a careful perusal of a novel and some short stories that I was so misguided as to write back in 1920. So, naturally, I feel a certain responsibility toward a generation which started life under so many warning fingers. This article is not a defense of the legendary ‘wild young person’; it is an attempt to formulate some of the ideas abroad in my generation — in particular as to the education of their own children. These may be the opinions of only two parents out of every two thousand but, in the world of ideas, the opinion of the vast dull majority is of no possible importance anyhow.”

Wait Till You Have Children of Your Own – F. Scott Fitzgerald

The original younger generation (I mean, of course, the one that burst forth back in 1919 and got itself thoroughly talked over) used to be periodically squelched with that ominous refrain. Well, the original younger generation are parents now. They are looking at the new world which has established itself out of the confusion of the war, and trying to decide just how their children’s education shall differ from their own.

When I say education I mean the whole bag of habits and ideals and prejudices that children receive from their parents between the ages of two and sixteen. I mean more than that-I mean what my own father meant when he said one day that he hoped my life would be different from his. He wanted me to have a better equipment than he had with which to face the world.

All parents want that for their children-except those so smug and self-satisfied that they hope their children will be exactly like themselves. For one parent who sits back at forty now and says to his offspring:

“Look upon this perfect man (or woman) that the Lord made as an example for you”-

There are three who believe the children should be an improvement on their parents, who want their children not to follow blindly in their steps but rather to profit by their mistakes.

Now, ideals, conventions, even truth itself, are continually changing things so that the milk of one generation may be the poison of the next. The young Americans of my time have seen one of these transformations with their own eyes, and for this reason they will not make the initial mistake of trying to teach their children too much. Before a man is thirty he has already accumulated, along with a little wisdom, a great quantity of dust and rubbish in his mind, and the difficulty is to let the children profit by what is wise without unloading the dust and rubbish on them too. We can only try to do better at it than the last generation did-when a generation succeeds in doing it completely, in handing down all its discoveries and none of its delusions, its children shall inherit the earth.

To begin with, my child will have to face conditions of which I am utterly unaware. He may live in a communist state or marry a girl from Mars or sit under an electric fan at the North Pole. Only one thing can I be sure of about the world in which he will live it will not be as cheerful a world as the world into which I was born. Never had faith in the destiny of man reached such a height as during the nineties seldom has it ebbed so low as it has now. When we see around us a great decay in ideals of conduct there is some fundamental cause behind it. It is impossible to be vicious in a vacuum. Something serious (which only professional evangelists, cheap novelists, and corrupt politicians profess to understand) is the matter with the world. It will be a strong heart that can fight its way upstream in these troubled waters and not be, like my generation, a bit cynical, a bit weary, and a bit sad. We have seen the war and its attendant ferocity, the hysteria both of the communists and, over here, of the “100% Americans,” the cheating of the wounded veterans, the administration corruption, the prohibition scandal-what wonder if we are almost afraid to open the newspapers in the morning lest our eyes fall on some new rift in civilization, some new vileness in that dark chamber which we call the human heart!

On such a world our children are now opening their eyes. Not long ago I was in a room where lay a young mother whose first child had just been born. She was a young woman of exceptional culture and education who had always had the good things of this world and who can expect to have them until she dies. When she awakened from the ether she turned to the nurse with a question, and bending over her the nurse whispered: “You have a beautiful little girl.”

“A girl?” The young mother’s eyes opened and then closed again. Suddenly she began to cry.

“All right,” she said brokenly, “I’m glad it’s a girl. And I hope she’ll be a fool-that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool!”

Of course, despite everything, few of us are sick enough, or perhaps logical enough, for such pessimism. We do not want our daughters to be beautiful little fools nor our sons to be mere “healthy animals,” despite the suffering that it might save them. More than that, we want them to have ideas above the bank book and the comfortable house. We want them to be decent, honorable, and, if I can no longer conscientiously add law abiding, at least capable of voting against laws which they cannot obey.

I can imagine a young father born as I was in the middle nineties talking somewhat like this to his brand-new son:

“I don’t want you to be like me,” he says, standing over the baby’s bed, “I want you to have time for the finer things in life. I want you to go into politics where not one man in ten has clean hands, and keep your hands clean. Or if you’re a business man I want you to be a better kind of business man than I am. Why, my son, except for a few detective stories, I haven’t read a book since I left college. My idea of amusement is to play golf or bridge with a lot of people just as dumb as I am, with a bottle of bootleg gin on the side so we won’t know how dull we are. I don’t know anything about science, or literature, or art, or architecture, or even economics. I believe everything I read in the papers, just like my janitor does. Except for my business I’m almost a halfwit, scarcely fit to vote-but I want you to be something better, and I’m going to give you a chance, so help me God.”

Now, that isn’t at all what his own father said to him way back in 1896. The older man probably talked something like this:

“I want you to be a success. I want you to work hard and make a lot of money. Don’t let anybody cheat you, and don’t cheat anybody else, or you’ll get put in jail. Remember, you’re an American”-(here substitute Englishman, Frenchman, or German, for the same speech was being made in many languages)”and we’re much better than any other race, so just remember that everything we don’t believe right here in this nation is pretty sure to be wrong. I went to college and I read the papers, so I ought to know.”

You recognize this? It is the philosophy of the nineteenth century, the philosophy of personal selfishness and national conceit that led to the great war and was indirectly responsible for the bloody deaths of many million young men.

At any rate, the new baby, our baby, starts out with something a little different. Having been in the war, and perhaps seen actual fighting, his father doesn’t hate the Germans he leaves that to the non-combatants-and maybe he remembers that life in Paris can be just as pleasant as life in Podunk, Indiana. He doesn’t give a whoop whether his son sings the national anthem in school, because he knows that surface patriotism means less than nothing, and that Grover Cleveland Bergdoll’s childish treble once piped out “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” at Teacher’s command. This young father hasn’t any unnatural faith in the schools anyhow-good as they are–because he knows the teachers are people just like him, not geniuses, but simply hard-working, half-educated young men and women who earn their bread by doing the best they can. He knows that the schools are of necessity a stereotyping agency in a somewhat stereotyped country. What the child will learn are the ideals of a busy shopkeeper, with side glances at the pictures of Abraham Lincoln and George Washington on the wall-those two romantic Presidents who are fast being made into illustrations for Sunday school books by silly biographers and sloppy short-story writers.

To the young father knows that his children are not likely to find ideals in school with which to face the modern world. If the child’s soul is going to bear any imprint except a few outworn rubber stamps, he must get his inspiration at home. A school system is such a colossal undertaking that it must often be regulated by convenience. But the young father does not have to tell his children shoddy lies about life because of convenience. And I don’t believe he will-the bitterest critics of this generation cannot accuse it of mock modesty. Its children will have at least that advantage over my contemporaries, who learned all the filthy words in the English language before they knew anything of the side of life they so grossly misrepresented.

Now I don’t mean to give the impression that the young men and women of my generation are bulging with a hundred sure-fire ways of turning children into veritable Abraham Lincolns. On the contrary, they will be inclined to protect their children from the canned rubbish at large in the world. They know that the knowledge of one good book, Van Loon’s “Story of Mankind” for example, is worth a list of a hundred “Children’s Classics compiled by some senile professor. And as they dread canned culture for their child so more than against anything else will they protect him from the canned inspiration that has become a national nuisance. The friendship of one older man of wisdom and character is a great boon-but such men are rare, there are not three to every city. And the substitute, the lectures by professional educationalists and boy-thrillers, represents, I think, a very real danger.

It is the danger of overstimulation. A boy or a girl that comes home every day from school with a new idea about beautifying the home or collecting old clothes for the Laplanders or making one noble sacrifice every week, is not a boy or girl whose brain will be anything but a cluttered bird’s nest in a few years. I do not want my child’s mind stimulated by every quack in the world, from paid patriots to moving-picture magnates who have rummaged among the ash heaps for shoddy ideas to give to the young. Eventually, of course, the child will grow tired both of the radio and of uplifting the neighbors, and there is no individual means of diversion to which I object-but the continual round of them dulls a child’s enthusiasm and permanently injures his mind. He is unable to enjoy or even to understand everything that is not presented to him in canned, predigested form-canned music, canned inspiration, even canned play-until it is no wonder that when he is a man he will be ripe for canned opinions and canned ideals.

“But,” objects the realist, “your children will grow up like mine into a world over which you have no control. If you forbid him all these things, will you not be setting up a ring of prohibitions around him-just as a short while since you objected to having about you?”

I’m going to try and answer that question, but first I want to discuss one important respect in which my child’s attitude toward life will be different from my own.

It is simply this: whatever respect he may hold for the opinions of age will be taken from him. Unless my mind fails and I join the common conspiracy to teach children that their parents are better than they are, I shall teach my child to respect nothing because it is old, but only those things which he considers worthy of respect. I shall tell him that I know very little more than he knows about the purpose of life in this world, and I shall send him to school with the warning that the teacher is just as ignorant as I am. This is because. I want my children to feel alone. I want them to take life seriously from the beginning with neither dependency nor a sense of humor, and I want them to know the truth-that they are lost in a strange world compared to which the mystery of all the caves and forests is as nothing. The Russian Jewish newsboy on the streets of New York has an enormous commercial advantage over our children, because he feels alone. He is aware of the vastness and mercilessness of life, and he gets his own knowledge of humanity for himself. Each time he falls down he is not picked up and set on his feet.

I cannot give my son that advantage without exposing him to the thousand dangers of a vagabond’s life-but I can make him feel mentally alone, as every great man has been in his heart-alone in his convictions which he forms for himself, and in his character which expresses those convictions. Not only will I force no standards on my son but I will question what others tell him about life. A supreme confidence is one of a man’s greatest assets, and we know from the story of our great men that it comes only through self-reliance and nothing that can be told my son will be of any value to him beside what he finds out for himself. All I can do is watch the vultures who swarm outside with conventional lies for his ear. The best friend we ever have in our adolescence is the one who teaches us to question and to doubt -I would be that kind of friend to my son.

Here, then, are five ways in which my child’s early world will be different from my own:

First-He will be less provincial, less patriotic. He will be taught that a citizen of the world is of more value to Podunk, Indiana, than is a citizen of Podunk, Indiana, to Podunk, Indiana. He will be taught to look closely at American ideals, to laugh at those that are absurd, to scorn those that are narrow and small, and give his best to those few in which he believes.

Second-He will know everything about his body from his head to his feet before he is ten years old. It is better that he should know this than that he should learn to read and write.

Third-He will be put as little as possible in the way of constant stimulation whether by men or by machines. Any enthusiasm he has will be questioned, and if it is mob enthusiasm-he who lynches negroes and he who weeps over Pollyanna is equally low at heart-it will be laughed out of him as something unworthy.

Fourth-He shall not respect age unless it is worthy in itself, but he shall look with suspicion on all that his elders say. If he does not agree with them he shall hold his own opinions rather than theirs, not only because he may prove to be right but because he must find out for himself that fire burns. Fifth-He shall take life seriously and feel always alone: that no one is guiding him, no one directing him, and that he must form his own convictions and standards in a world where no one knows much more than another.

He’ll have then, I hope with all my heart, these five things-a citizenship in the world, a knowledge of the body in which he is to live, a hatred of sham, a suspicion of authority, and a lonely heart. Their five opposites-patriotism, modesty, general enthusiasm, faith, and good-fellowship-I leave to the pious office boys of the last generation. They are not for our children.

That much I can do further than that it depends on the capabilities of the boy on his intelligence and his inherent honor. Let us suppose that, having these things, he came to me at fourteen and said:

“Father, show me a good great man.” I would have to look around in the living world and find someone worthy of his admiration.

Now no generation in the history of America has ever been so dull, so worthless, so devoid of ideas as that generation which is now between forty and sixty years old the men who were young in the nineties. I do not, of course, refer to the exceptional people in that generation, but to the general run of “educated” men. They are, as a rule, ill-read, intolerant, pathetic in their mental and spiritual poverty, sharp in business, and bored at home. Culturally they are not only below their own fathers who were fed on Huxley, Spencer, Newman, Carlyle, Emerson, Darwin, and Lamb, but they are also below their much-abused sons who read Freud, Remy de Gourmont, Shaw, Bertrand Russell, Nietzsche, and Anatole France. They were brought up on Anthony Hope and are slowly growing senile on J. S. Fletcher’s detective stories and Foster’s Bridge. They claim that such things “relax their minds,” which means that they are too illiterate to enjoy anything else. To hear them talk, of course, you would think that they had each individually invented the wireless telegraph, the moving picture, and the telephone-in point of fact, they are almost barbarians.

Whom could my generation look up to in such a crowd? Whom, in fact, could we look up to at all when we were young? My own heroes were men my own age or a little older men like Ted Coy, the Yale football star. I admired Richard Harding Davis in default of someone better, a certain obscure Jesuit priest, and, occasionally, Theodore Roosevelt. In Taft, McKinley, Bryan, Generals Miles and Shafter, Admirals Schley and Dewey, William Dean Howells, Remington, Carnegie, James J. Hill, Rockefeller, and John Drew, the popular figures of twenty years ago, a little boy could find little that was inspiring. There are good men in this list-notably Dewey and Hill, but they are not men to whom a little boy’s heart can go out, not men like Stonewall Jackson, Father Damien, George Rogers Clark, Major André, Byron, Jeb Stuart, Garibaldi, Dickens, Roger Williams, or General Gordon. They were not men half as good as these. Not one of them sounded any high note of heroism, no clear and distinct call to something above and beyond life. Later, when I was grown, I learned to admire a few other Americans of that generation-Stanford White, E. H. Harriman, and Stephen Crane. Here were figures more romantic, men of great dreams, of high faith in their work, who looked beyond the petty ideals of the American nineties. Harriman with his transcontinental railroad, and White with his vision of a new architectural America. But in my lifetime these three men, whose free spirits were incapable of hypocrisy, moved under a cloud.

Now, ten years from to-day, I hope that if my son aches to me and says, Father, show me a good man,” I can point out something better for him to admire than shrewd politicians or paragons of thrift. Some of those who went to prison for their conscience’ sake in 1917 are of my generation, and some who left legs and arms in France and came back to curse not the Germans but the “dollar-a-year men” who fought the war from easy chairs. There have been writers already in my time who have lifted up their voices fearlessly in scorn of sham and hypocrisy and corruption-Cummings, Otto Braun, Dos Passos, Wilson, Ferguson, Thomas Boyd. And in politics there have been young men like Cleveland and Bruce at Princeton, whose names were in the papers before they were twenty because they scrutinized rather than accepted blindly the institutions under which they lived. Oh, we shall have something to show our sons, I think-to point at and say not, perhaps, “There is a perfect man,” but “There is a man who has tried, who has faced life thinking that it could be fuller and freer than it is now and hoping that in some way he could help to make it so.”

The women of my generation present a somewhat different problem-I mean the young women who were lately flappers and now have babies at their breasts. Personally I can no more imagine having fallen in love with an old-fashioned girl than with an Amazon-but I think that on the whole the young women of the well-to-do middle classes are somewhat below the men. I refer to the dependent woman, the ex-society girl. She was pretty busy in her adolescence, far too busy to take an education, and what she knows she has learned vicariously from a chance clever man or two that have come her way. Of a far better type are the working girls of the middle classes, the thousands of young women who are the power behind some stupid man in a thousand offices all over the United States. I don’t mean that she will bear a race of heroes simply because she has struggled herself on the contrary, she will probably overemphasize to the children the value of conformity and industry and commercial success–but she is a far higher type of woman than our colleges or our country clubs produce. Women learn best not from books or from their own dreams but from reality and from contact with first-class men. A man can live with a fool all his life untouched by her stupidity, but a smart woman married to a stupid man acquires eventually the man’s stupidity and, what is worse, the man’s narrow outlook on life.

And this brings on a statement with which many people will disagree violently, a statement which will seem reactionary and out of place here. I hope for the newest generation that it will not be so women educated as the last. Our fathers were too busy to know much about us until we were fairly well grown, and in consequence such a condition came about that, as Booth Tarkington justly remarked, “All American children belonged to their mother’s families.” When I said the other day before some members of the Lucy Stone League that most American boys learned to lie at some lady teacher’s knee, a shocked silence fell. Nevertheless I believe it to be true. It is not good for boys to be reared altogether by women as American children are. There is something inherent in the male mind that will lie to or impose upon a woman as it would never consider doing to a man.

If the boys at school don’t like you, come here to me, says the mother to her sons.

“If the boys at school don’t like you, I want to know the reason why,” says the father.

Properly the young boy needs to meet both these two attitudes at home, but my generation got only the first, and it made us soft; and we would still be soft, unpleasantly soft, if we had not had the two years’ discipline of the war.

And so, if the young men whom I see every day are typical of their generation, we have by no means hauled down our flags and moderated our opinions and decided to bring up our children in the “good old way.” The “good old way” is not nearly good enough for us. That we shall use every discovery of science in the preservation of our children’s health goes without saying; but we shall do more than this-we shall give them a free start, not loading them up with our own ideas and experiences, nor advising them to live according to our lights. We were burned in the fire here and there, but-who knows?-fire may not burn our children, and if we warn them away from it they may end by never growing warm. We will not even inflict our cynicism on them as the sentimentality of our fathers was inflicted on us. The most we will urge is a little doubt, asking that the doubt be exercised on our ideas as well as on all the mortal things in this world. Already they are on their hearth, charming us with strange new promises in their eyes as they open them upon the world, with their freshness and beauty and the healthy quiet with which they sleep. We shall not ask much of them-love if it comes freely, a little politeness, that is all. They are free, they are little people already, and who are we to stand in their light? They must fight us down at the end, as each generation fights down the one before, the one that is cluttering up the earth with all those decayed notions which it calls its ideals. And if my child is a better man than I, he will come to me at the last and say, not “Father, you were right about life,” but “Father, you were entirely wrong.

And when that time comes, as come it will, may I have the justice and the sense to say: “Good luck to you and good-by, for I owned this world of yours once, but I own it no longer. Go your way now strenuously into the fight, and leave me in peace, among all the warm wrong things that I have loved, for I am old, and my work is done.”

Podcast explaining the article’s relevance to The Great Gatsby