Users can also listen this story below

At 10.00am yesterday morning I received an email prompt from Google asking me to check out a new A.I feature called Gemini Storybook. I was busy proofing a book that I am writing on F. Scott Fitzgerald, but curious, I took a look. And I’m glad I did. It was fun to use. A great tool for primary schools. I uploaded an edited version of a chapter I’m working on, adapted it for a young audience and provided instructions for the pictures (you can let Gemini create the text but I wouldn’t recommend it). Here’s the result. Words by me, illustrations by Gemini Storybook.

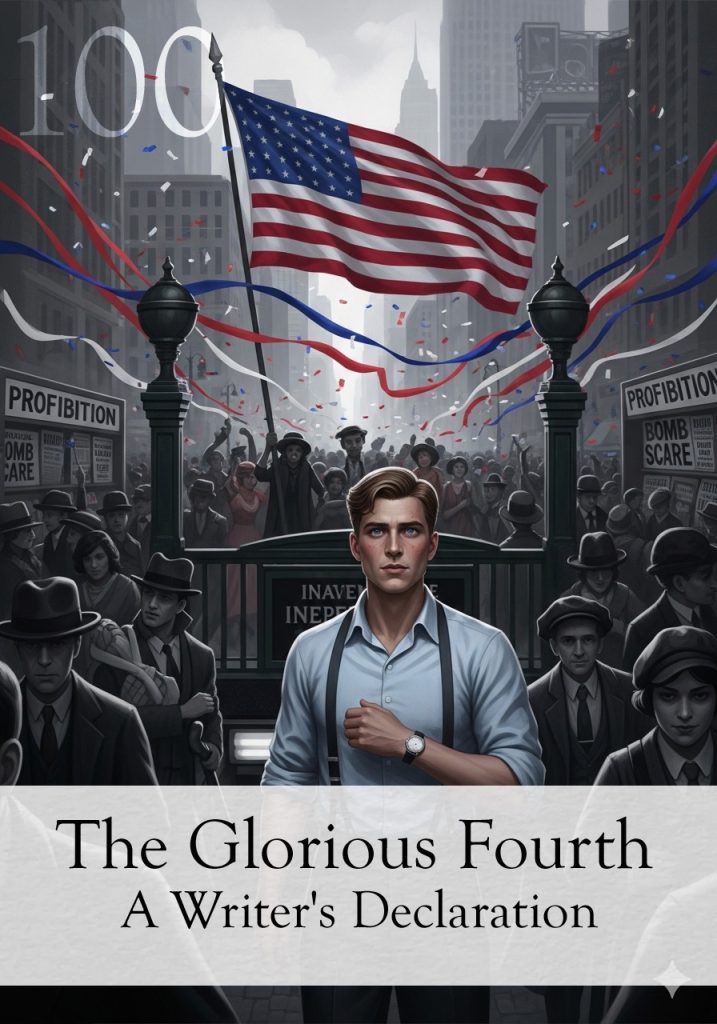

On the morning of Independence Day 1919, Scott was feeling utterly disgusted with himself and those around him. His days were spent at Barron-Collier Advertising, crafting snappy promotional jingles like “We keep you clean in Muscatine,” while his evenings were dedicated to his true passion: writing stories. This constant split left him feeling restless, a “cracked plate” in a city that promised so much.

He had made it to New York, but now, that wasn’t enough; he felt his talents emphatically wasting away, marooned somewhere between the gutter and the stars. By July 1919, New York had shed all its romantic allure for Scott. The cloud-topped towers of the tall white city, once glimmering with promise, had shrunk back to plain old tenement blocks and imposing office buildings. The New York of his imagination once had all the “iridescence of the beginning of the world.” Now it was tainted, a persistent betrayal of his original ideal.

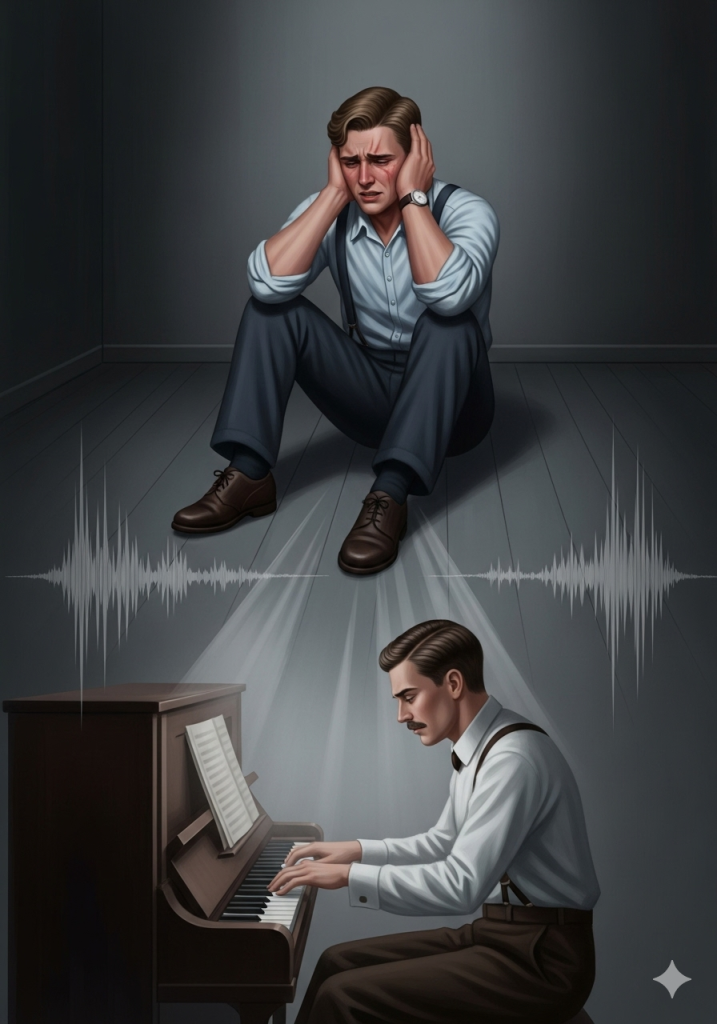

The city’s relentless noise and movement placed an overwhelming demand on his senses. From the apartment below, the composer Julius E. Andino would bang away at his ragtime piano, each pounding chord a constant, mocking reminder of a world that was making progress, while Scott felt utterly stuck, a disregarded pledge in a city of endless, unfulfilled promises. Sleep, too, had abandoned him. He’d wake up at 3:00 AM, and for the rest of the day, the clock would feel perpetually frozen at that hour. The minutes and hours that followed were nothing more than a dangerously thin protraction of that one last sticky hour, rambling, disjointed, and as seemingly infinite as long winter shadows.

Occasionally, a letter from Zelda would arrive, a brief spark of hope that would quickly fade. The happiness was always short-lived, as the sincerity of her messages would collapse under the sheer weight of expectation he placed on them. Maybe she loved him, maybe she didn’t love him. And even if she did, she might not love him enough. A ring had been bought, but any plans for a wedding remained a distant, shimmering mirage, leaving him in constant doubt. A process of self-disintegration was setting in, threatening to dissolve him entirely.

On the night of July 3rd, Scott got “roaring weeping drunk,” a desperate attempt to escape the oppressive reality of a city that had gone bone dry with the Wartime Prohibition Act. The next day — Independence Day — he made a beeline for the subway. A new kind of freedom was beckoning, away from the powder keg of a city rife with bomb scares and a pervasive sense of disillusionment.

With his last few dollars, Scott hopped into one of the train cars of the Chicago, Milwaukee & Saint Paul Pacific railroad, heading back home to Saint Paul. He was making it out of the city just in time, escaping the record-breaking heat of a July Fourth nudging 100°F, the constant bomb scares, and the pervasive disillusionment that had settled over New York. As the train pulled away, a new horizon began to open.

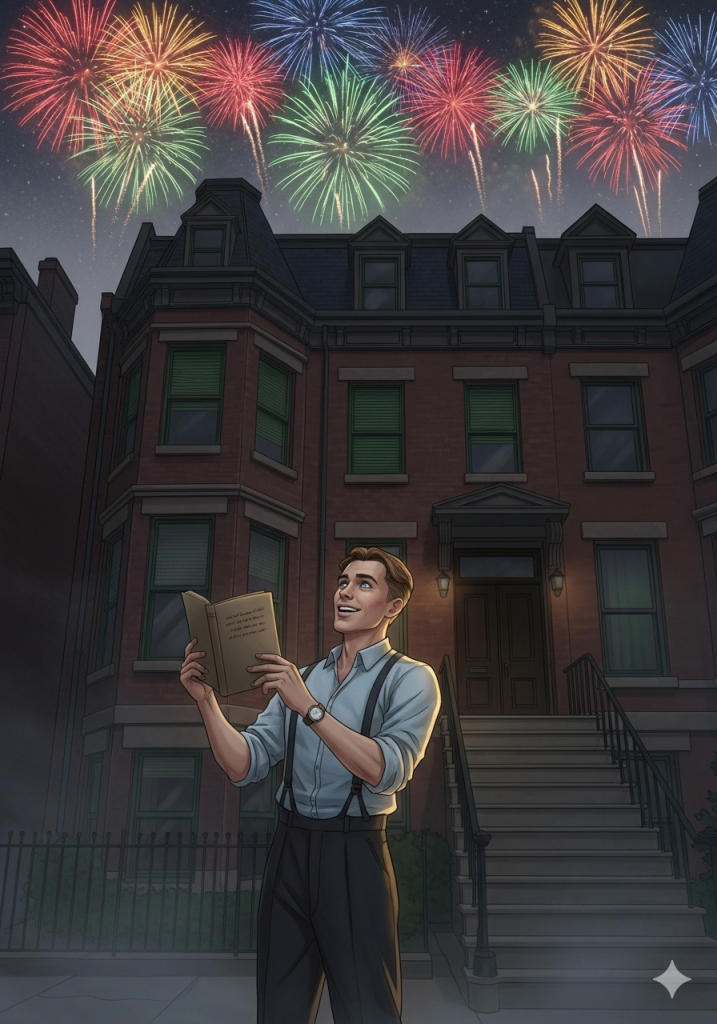

During the long, hot journey home, Scott pulled out a copy of Hugh Walpole’s Fortitude. As he turned the book’s pages, a profound realization dawned on him: this was what the life of a young author was meant to be like. “It’s not the number of years you live that really matters. It’s what you put into those years that count,” read one passage.

The keynote of a man’s life had to be quality, not quantity; it wasn’t life that mattered, but “the courage you brought to it.” The words fuelled his hungry soul. The black shadow that had hung over him for the past few months had finally started to lift. From this moment on, he would become a full-time writer, subject to no interest but his own and his incomparable love for Zelda.

He was punching in new coordinates for his life, embarking on a path of self-determination. If he wasn’t to lose the girl of his dreams, he had to finish the novel. He had made his declaration; he was getting out. What better day to break with tradition, to go rasping against the grain, than July 4th? Like a child in the thrall of New Year celebrations, the build-up to this day, the thought of firecrackers and parades, had energized and bewitched the young author in the most profound way. He packed his suitcase and boarded the train, saving whatever was left of his freedom.

When he eventually arrived home on the evening of July 4th, 1919, Scott’s parents, Edward and Mollie Fitzgerald, were already making merry at the White Bear Yacht Club, celebrating his sister Annabel’s coming of age, totally unaware of the profound declaration Scott had made. In glory or in failure, he had made it home. The independence he had sought, both as an individual and an artist, was finally his for the taking, a personal Fourth of July.

by Alan Sargeant