Among the mourners at the funeral of Scott’s grandmother, Cecilia Aston Scott Fitzgerald, in 1924 were the Forrest family, a distinguished Washington family whose ancestral home in Georgetown, Cecilia had stayed at during her early years in the capital. The head of the Forrest family was well-known government attorney Randolph Keith Forrest, the nephew of Captain French, the former commander of the Norfolk Navy Yard who, like the Fitzgeralds’ infamous in-law, John Surratt, had served the Rebel cause. An entry in Scott’s ledger records that he stayed with his grandmother and the Forrest family in March 1912 after a trip to see his aunt not far from the famous naval base in Norfolk City. [1]

27-minute summary and discussion on Fitzgerald and The Washingtons

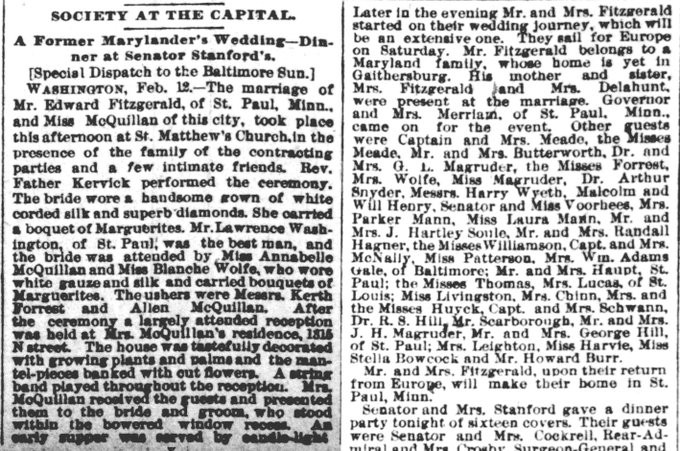

In all likelihood it was the death of Scott’s grandmother that had brought his parents back to the capital in the early 1920s, where they resided at Meridian Mansions, 2400 Sixteenth Street. Some thirty-five years earlier, Edward and Mollie had married at Saint Matthews Cathedral just a few hundred yards west of Sixteenth Street. At the time of their marriage the couple were staying with Scott’s maternal grandmother, Louisa. A local newspaper reported that Mary wore a gown of white corded satin with a high body, sweeping train and “superb diamonds”. A bridal veil of white was said to envelope her like a cloud and her bouquet was composed of Marguerites. The picture painted in the report was anything but showy. The mantelpiece of the house had been banked with cut flowers and there were garlands of plants and palms throughout. During the reception that followed, a string-quartet played a selection of mellow tunes by Pachelbel, Bach and Mendelssohn, and a supper was served by candlelight. Edward’s best man that day was Lawrence Gibson Washington. According to a 1922 news item, Lawrence was a descendant of the family of America’s founding president, George Washington. His family home in Saint Paul at this time, 587 Summit Avenue, was just doors away from the house where Scott completed his first novel. After returning to Saint Paul jobless in 1908, Edward and Molly had lived with oculist Dr John Farquhar Fulton Snr and his wife whilst Scott and his sister Annabel enjoyed all the various benefits of life with their grandmother on Laurel Avenue. After years of bouncing around from family to friends, Edward and Molly settled on Summit Avenue some time in 1914.

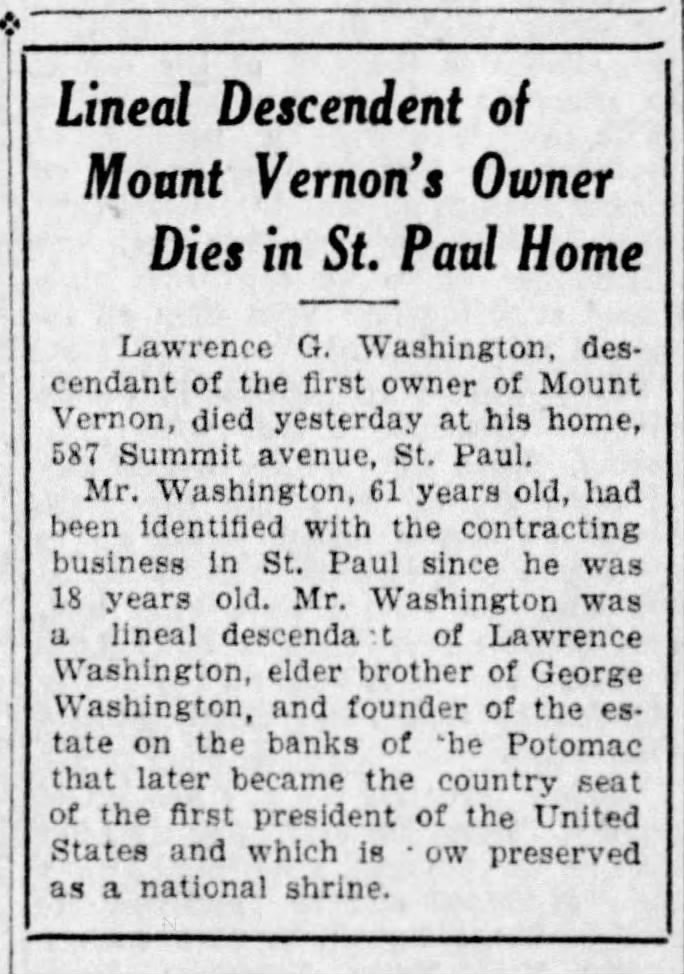

His 1922 obituary revealed that Lawrence Washington had lived in Saint Paul since the age of eighteen and that his own line went back not to George Washington but to George’s older brother, Lawrence. Richard’s mother, Sarah Tayloe Washington (b.1800), was the daughter of Colonel William Augustine Washington, the President’s nephew. A story in a New Jersey newspaper told how Sarah vividly recalled visiting the homesteads on which George and generations of the Washington family had been raised at the Popes Creek Plantation. The original houses had long since been abandoned and their bricks carried off by relic hunters. [2] After a modicum of success in the California Goldrush of 1849, Lawrence’s father Richard Bushrod Washington (b. 1827) had moved from Virginia to Hastings, Minnesota. At the start of the civil war Richard went back to Virginia to serve as an orderly sergeant in the 9th Virginia Cavalry regiment in the Confederate Army under J. E. B Stuart. According to several sources he died at the Battle of Hagerstown (Williamsport) in Maryland in July 1863.[3] It was in June that year that Stuart’s 5,000 strong cavalry unit arrived in Gaithersburg and Rockville, the home of Scott’s father Edward and his family not far from Clopper’s Mill. [4] Once in Rockville, Stuart and his men quickly established a network of intelligence gatherers among townsfolk sympathetic to the Confederate cause. A write-up of the raid in the Unionist newspaper, the Harrisburg Patriot painted a clear picture of the support they had in the area: “Rockville has never been noted for its loyalty”, the paper snorted. Clopper’s Mill, owned by Michael and Cecilia Fitzgerald’s neighbour, Francis Clopper, would subsequently feature in the trial of George Atzerodt, an accomplice of John Wilkes Booth and John Surratt in the Lincoln kidnap and assassination plots. On April 15 1865, and already being pursued by Pinkerton detectives, Atzerodt had made his way by stage to Rockville where he proceeded on foot towards Gaithersburg. Upon reaching Clopper’s Mill he was put up for the night by its operator, Robert Kinder. A short time later he found a more permanent hiding place at his cousin’s house in nearby Germantown. [5]

Star Spangled Banner

A story in the Saint Paul Daily Globe in the year that Scott was born tells how Lawrence, a wealthy building contractor and stone merchant, had served as one of several ushers as the city celebrated the 164th birthday of America’s founding father, George Washington. ‘They Loved George’, roared the headline. [6] As a passionate member of the Sons of the Revolution, Lawrence was a regular feature at patriotic events in the city. At one such event in 1898, over a thousand children had joined him in singing a rousing selection of patriotic songs at the People’s Church on Pleasant Avenue. Hanging proudly over the pulpit was a portrait of Washington whilst elsewhere in the church were ‘stations-of-the-cross’ style engravings of the President crossing the Delaware River and other celebrations of his many heroic deeds. Among the songs the children sung that day were The Battle Hymn of the Republic and Our Bright Starry Banner. The Star Spangled Banner, written by Francis Scott Key, a distant forebear of Scott, was saved for last, their voices rising in a thrilling crescendo. For men like Lawrence, the flesh and blood of the Revolution had become the channel of America’s glowing, progressive spirit. ‘Loyalty, loyalty, loyalty’, the children whispered in communion, passing the wafers of devotion between them in a dignified observation of the faithful repetition of time. [7] For F. Scott Fitzgerald, the man who would, for many people, become the keeper of the American Dream, it was probably the best start in life one could get. Here was his father Edward, the son of a prominent Maryland family, with the fourth generation kin of the very first American President standing by his side at his wedding. Scott must have felt like he’d been born with a story to tell. Other guests at Edward and Mollie’s wedding that day included William Rush Mirriam, the 11th Governor of Minnesota, Senator Daniel Voorhees, a Copperhead during the war, and several members of the family of celebrated rail magnate and national treasure, James J. Hill, a name that would eventually reappear in Scott’s third novel, The Great Gatsby.

The report of his parent’s wedding is interesting for several reasons, not least because it provides a vivid picture of the social circles that the McQuillan and Fitzgerald families moved in. It also may give us clues about how Edward and Lawrence met. A detailed look at the names of the guests reveals three serving naval captains: Captain Schwann, Captain Valentine McNally and Captain Richard Meade, commandant of the Washington Navy Yard. The music provided that day was by The Marine Band. Was it possible that Edward, Meade, McNally and Schwann had trained as marines together? Was it Washington’s Navy Yard that all four men had in common? A further clue may be provided by the house on N Street that Scott’s grandmother, Louisa McQuillan was occupying in Washington at this time and where the wedding took place. The local press report that her large four-storey brick house within a square at Thomas Circle had been leased from a naval man, Samuel L. Breese, the son of Illinois senator Sidney Breese and nephew of the infinitely more famous naval commander, RADM Samuel Livingston Breese — hero of the American Civil War. [8]

Breese wasn’t the only prominent naval man in the Fitzgerald family history. In 1903 Scott had acted as flower boy at the wedding of his cousin Cecilia Delihant to Virginia’s Richard Calvert Taylor (1871-1909), the son of a Confederate naval man who had once escaped to England. According to press reports at the height of the Civil War, Richard’s father, a paymaster on the military steamer, CSS Florida, had evaded capture of the ship by Union forces at Bahia. Once in London, Taylor and the ship’s Captain, C.M. Morris arranged a series of interviews with the British newspapers, anxious to quash the rumours of a brutal and bloody defeat in Brazil. Contrary to what was being said in the reports, none of the Confederate officers on board the ship had been killed. Any suggestion of a humiliating defeat were, they said, the work of propagandists and Federal spies. On his return to Virginia after the war, Richard and his family had settled in Norfolk City on a street in Colonial Place, close to the naval shipyards. It was this same house that Scott would visit both before and after he had become a writer. [9]

The Diamond as Big as the Ritz

The Diamond as Big As the Ritz is an extraordinary little fantasy whose surrealism and humour recall the best works of Roald Dahl and Jonathan Swift. In it, Scott takes aim at everything from capitalism, state government, heredity and religion. There isn’t a subject that is too precious to be mocked and the author’s sharp, satirical prose sparkles as brightly as old Fitz-Norman Washington’s jewel itself. But the most intriguing thing about his story is the family itself, which bears more than a passing resemblance to the family of Lawrence G. Washington, the best man at his father’s wedding: “This is a story of the Washington family as Percy sketched it for John during breakfast. The father of the present Mr. Washington had been a Virginian, a direct descendant of George Washington, Lord Fairfax and Lord Baltimore. At the close of the Civil War he was a twenty five-year-old Colonel with tremendous ambition, a played-out plantation and about a thousand dollars in gold.” [10] The similarities don’t end there. Lawrence’s father, Richard Gibson Washington is said to have made much of his money in gold and his uncle, George Corbin Washington, derived much of his fabulous wealth from the iron mining enterprises of his father and his grandfather. This particular branch of the Washingtons had, moreover, been among the largest slave owners in Maryland. It is also interesting to note that Lawrence’s thirteen year old son, Richard, would play the part of Diamond O’ Ranch cowpuncher, Tony Gonzoles, The Girl from Lazy J , an early play by Scott that was performed by the Elizabethan Drama Society in Saint Paul in 1911. The pair would meet up again in 1917 for a dinner dance in honour of their mutual friend, Genevieve Smith, in Saint Paul. [11] Social commentary aside, the story works very successfully as a personal and symbolic narrative about the evolution of his father’s dreams and the absurdities, lies and ambition that get passed from parent to child.

A story as irreverent as Diamonds was a bold move from Scott. It took shot after shot at the mechanisms of capitalism and the folly of excessive wealth. Arriving as it did at the time of the ‘Red Scare’ would scare a lot of publishers. A communist revolution had just taken place in Russia and they didn’t want the same thing happening in America. Whether it was served in the interests of satire or not, ‘Parlor Bolshevism’ was viewed by American publishers with enormous scepticism. The Red Scare had remapped the engine of American Conservativism, boosting national pride and accelerating hysteria. As a result, many magazines were terrified of printing anything that might generate the wrong type of publicity for advertisers. The story was eventually rejected by the Saturday Evening Post and taken up instead by George Nathan and H. L. Mencken’s The Smart Set. Compared to the $1300 fees he was picking up from the Post for stories, the $300 paid by The Smart Set was an absolute bargain by comparison. At this time the two editors of the magazine were still hosting frequent late-afternoon parties at Nathan’s apartment. Scott would provide the cocktails, Mencken would provide the gin and vermouth and Kay Laurell would occasionally drift in from Edgar Selwyn’s parties in Great Neck to provide the gossip and entertainment.

Scott’s biographer, Matthew J. Bruccoli quite rightly observed that the hallucinatory quality of Diamonds lends itself well to allegorical interpretations but that the meanings of the story are abundantly clear from the start: “absolute wealth corrupts absolutely and possesses its possessors”. [12] There is, however, a topical dimension that appears to have been overlooked. This relates to the explanation that Scott provides for how Fitz-Norman Culpepper Washington is able to derive wealth from the diamond without actually giving away his secret. The strategy he had used had been to convert all his existing millions into stockpiling the most expensive element in the world — radium. In an effort to preserve his secret, Washington has convinced the world that he is a producer of radium, not diamonds. In Scott’s story “the equivalent of a billion dollars in gold” had been placed by Washington “in a receptacle no bigger than a cigar-box”. [13] Radium was big news when Scott was writing the story. In May 1921, just as he and Zelda were arriving in France, Madame Curie, the world-famous scientist known for her groundbreaking work on radioactivity, had made her way from The Radium Institute in the Latin Quarter of Paris to Washington D.C where on Friday the 20th she met with President Harding and a cheerless consortium of military personnel at the White House. At the ceremony, the scientist was being gifted with one gram of radium to help with her research, a reward for her support of the allies during the war, both on radiography and selling war bonds. The radium was presented to Curie in a beautiful lead-lined mahogany case no bigger than a shoe box in the Blue Room of the White House. The value of the gram was said to be $100,000 — a figure that many Americans would have had a hard time processing for a piece of metal no bigger than a ‘peanut’. During the ceremony Harding, masking his rather limited understanding of the science with a more palatable sugar-coating of symbolism, attempted to invest Curie’s work with a quasi-religious dimension: “I have liked to believe in an analogy between the spiritual and the physical world. I have been very sure that that which I may the radio-active soul or spirit, or intellect must first gather to itself from its surroundings, the power that afterwards radiates in beneficence to those near it.” [14] For Harding, it wasn’t a lump of brilliant white metal she was holding in her hands that day but the “sum of many aspirations, borne in on great souls” to “illuminate the world” around them. Curie had gone to the White House to be given a simple mahogany box and left with the glowing and ever so slightly radioactive torch of Lady Liberty in her hands. No wonder the statue looked so green at Liberty Island — it was riddled with radiation.

Researched and written by Alan Sargeant 2024

[1] US census 1910, Precinct 7, Washington, District of Columbia, United States, 3339 N Street, April 1910; Georgetown Architecture-Northwest; Northwest Washington: District of Columbia. (1970). United States: US Commission of Fine Arts, pp.184-187.French Forrest had been born in Maryland. His brother Bladen Forrest was a prominent Washington slave owner. The family later worked in government law.

[2] ‘The Washington Family’, Newark Daily Advocate, July 30, 1894, p.2

[3] History of Saint Paul and Vicinity, Lewis Publisher, Chicago, 1912, p.876-77; ‘Lineal Descendant of Mount Vernon’s Owner Dies in St Paul Home’, February 21, 1922, p.1;The Washingtons. Volume 4, Part 2, Justin Glenn, Savas Beatie, 2014, p.1866. Richard Bushrod Washington certainly appears in several books on the Washington lineage. His son Lawrence Gibson Washington and his wife Ellen Center appear in the 1860 census in Hastings. Richard’s mother married her 5th cousin.

[4]‘Trustee’s Sale’, Montgomery County Sentinel, June 12, 1857, p.3. According to Arthur Mizener their farm was called Glenmary. The American poet Nathaniel Parker Willis named his own 200 acre farm and orchard Glenmary. He was closely associated with Edgar Allen Por, a favourite in the Fitzgerald family.

[5]The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence, William C. Edwards, University of Illinois Press, 2009 p 781. Clopper’s wife was catholic and he donated generously to the building of the nearby Catholic Churches.

[6] ‘They Loved George’, Saint Paul Globe, February 22, 1896, p.10. It was the year of Scott’s birth. Lawrence also lived on Summit Avenue.

[7] ‘Little Patriots’, Saint Paul’s Globe, February 23, 1898, p.8

[8]Washington Evening Star, September 25, 1889, p.2.

[9]‘The Capture of the Florida’, Atlas (The Englishman), November 12, 1864, p.6; Rush, R. (1896). Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion: Ser. I, V. 1-27, Ser. II, V. 1-3. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, p.866. The house that Scott visited in Norfolk City was on what is now, Gosnold Avenue (previously Grafton Avenue, see US Census 1910, Cecilia Delihant Taylor, Norfolk City, Ward 7, Virginia). Richard Taylor arrived back in Virginia to found several prominent banks. Also in the extended Taylor family was Commodore Perry and William Conway Whittle, the executive officer and an navigator of the Confederate blockade runner CSS Shenandoah. The ancestral home is the Taylor-Whittle House at Freemason Street.

[10] The Diamond as Big as The Ritz, F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Smart Set, June, 1922, p.12

[11] Minneapolis Journal, August 20, 1917, p.12

[12]Some Sort of Epic Grandeur, Matthew J. Bruccoli, p.

[13] The Diamond as Big as The Ritz, F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Smart Set, June, 1922, p.13

[14] ‘Harding Hands Gift of Radium to Mme. Curie’, New York Tribune, May 21, 1921, p.9 ; ‘Mme. Curie Sails for France To-day’, New York Tribune, June 25, 1921, p.7.