You can download an updated and extended version of this mini-book (including copious footnotes and sources) by clicking here (PDF).

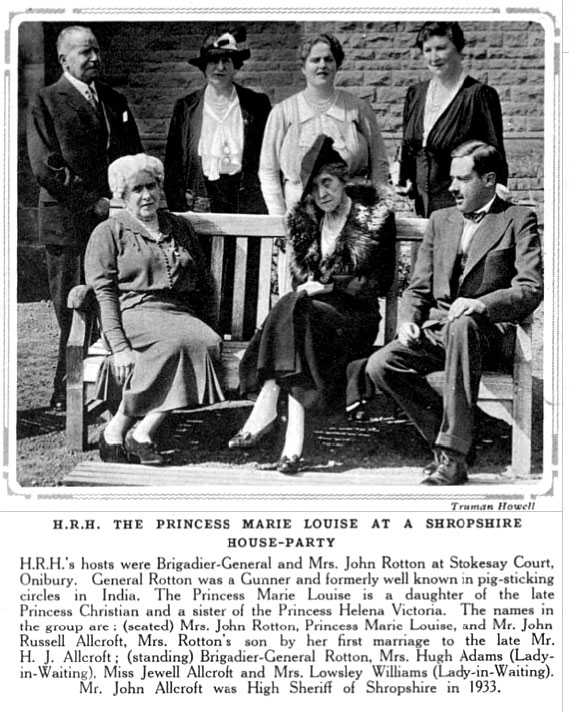

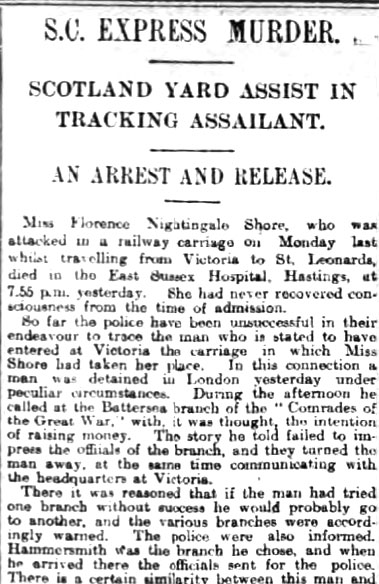

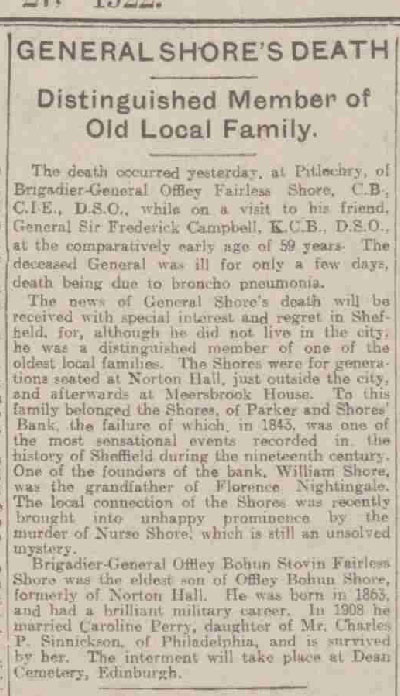

If you watched Tom Dalton’s Agatha Christie and the Truth of Murder whodunit on Channel 5 over Christmas, or have read Rosemary Cook’s The Nightingale Shore Murder then you’ll know some of the story already. On January 12th 1920, the goddaughter and second cousin of Lady of the Lamp, Florence Nightingale enters the carriage of a London-to-Brighton South East Express train and is found beaten and left for dead in the same, sealed compartment as the train enters Bexhill-on-Sea, the resort on the East Sussex coastline whose rakish cadre of military retirees and ‘Ginger Cat’ tea-rooms are evoked so vividly in Christie’s ABC Murders. There are no signs of a violent struggle, and the lady’s dressing case is found as originally placed. On her lap is an open book, and by her side an attaché case, its lock torn open and some of its contents partially displayed. A young man in a brown suit is said to have followed her into the compartment as the train left Victoria Station. An amethyst pendant originally reported missing was subsequently found and other jewellery was in a dressing case back at home (Daily Herald 16 January 1920 p.1).

Her murderer and his motive remains unknown to this day.

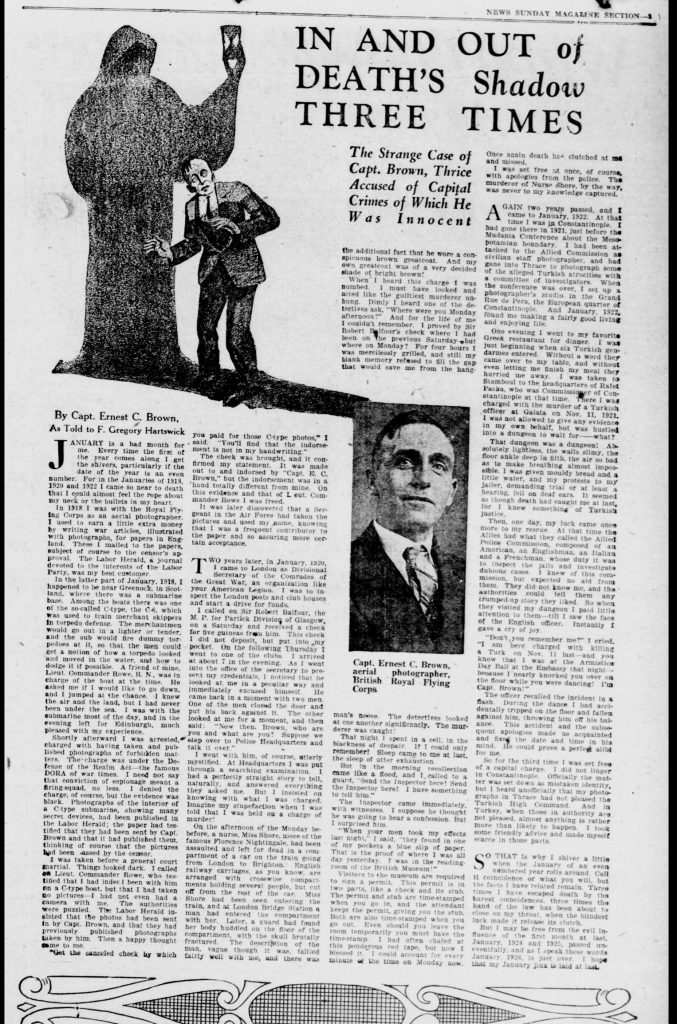

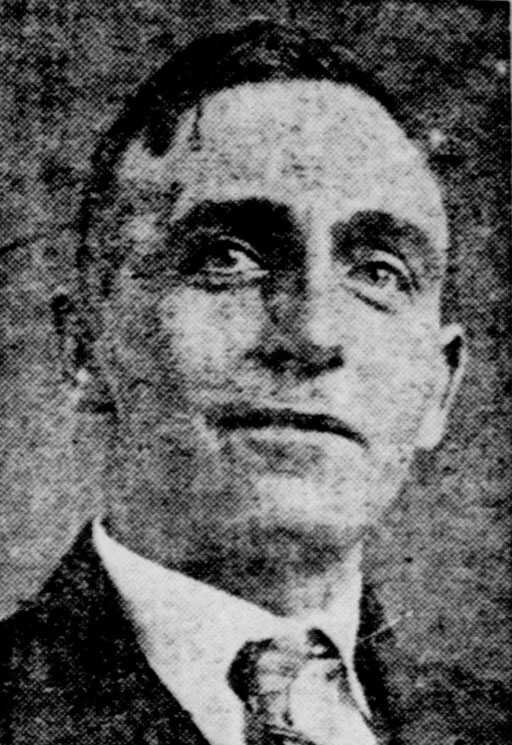

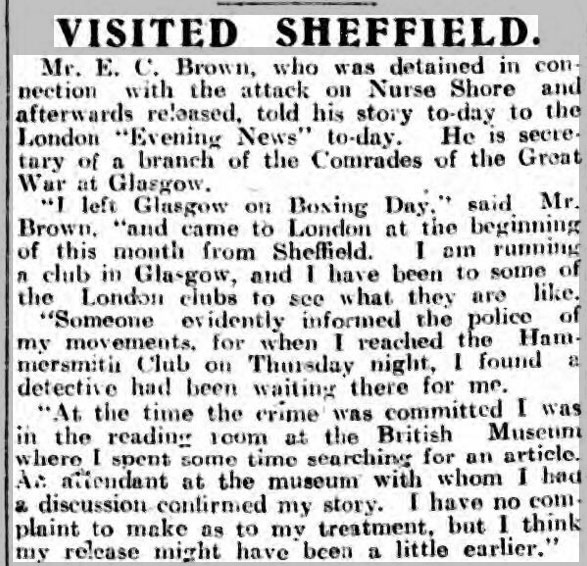

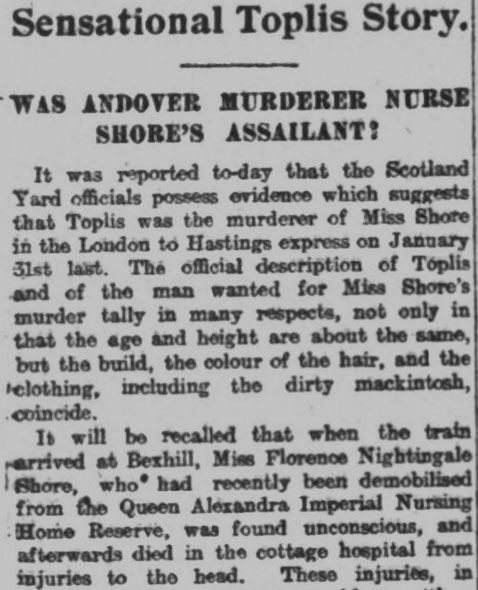

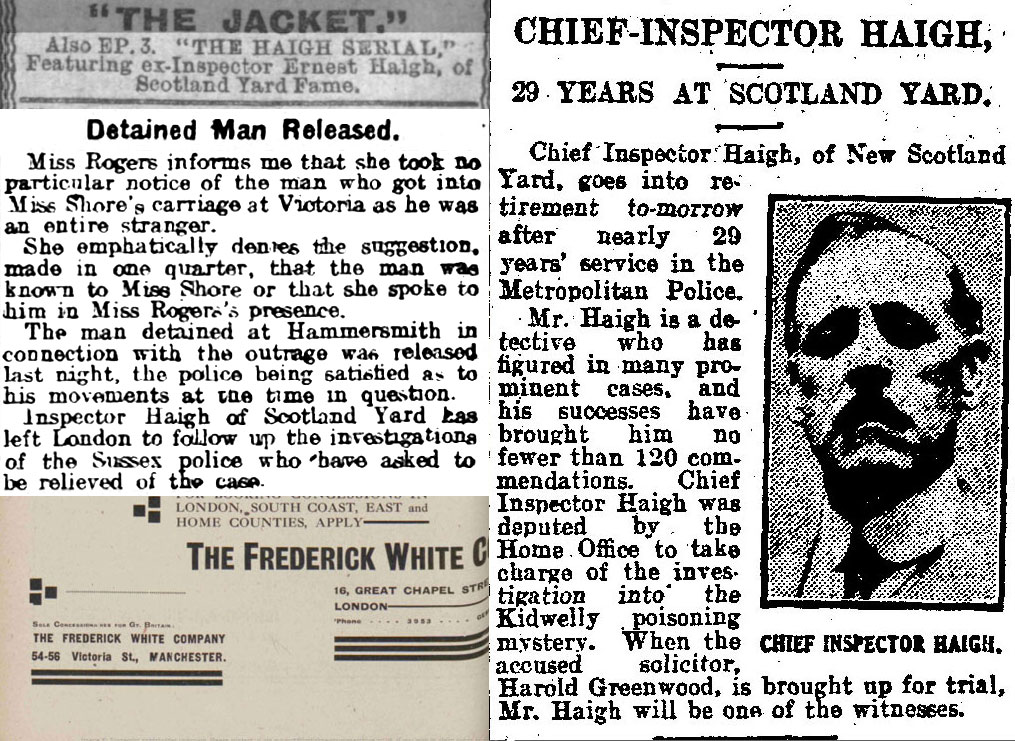

One of the most famous suspects in the case was Percy Toplis, but what many people won’t have been told until now, is that the first man arrested by Police was Ernest C. Brown 1, a former Captain in the RAF and branch division President of the Comrades of the Great War in Glasgow. Both men matched the description of the ‘man in the brown suit’ who was alleged to have travelled alongside Florence in the train carriage that day (Train Outrage Mystery, Aberdeen Press and Journal, 19 January 1920, p.5).

Until now, little about Ernest C. Brown was known, but an interview he gives to the American press in 1926 casts new light on the mystery, as Ernest admits to having been a suspect in a further two unsolved mysteries in a period spanning four years. In each case, the scope and potential for espionage is substantial to say the least. His secondment to the Inter-Allied Commission as staff photographer in Constantinople in 1921 is particularly intriguing as this was a critical period politically and economically for Britain, Turkey and Russia. The fact that the brother of Florence Nightingale Shore had served as Military Attaché in Russia during the 1918-1920 Civil War, only adds to the layers of intrigue that starts with Brown’s alleged arrest as a possible spy in a Faslane story in 1918 2.

But all this pales in comparison with an entirely fresh discovery; the news that Nurse Shore’s cousin, Raffaele Farina, was a spy at Mi5 and played an instrumental part in explosive espionage scandal that helped crash Britain’s then-serving Labour government.

Brown’s Story

Ernest C. Brown’s story was told in the Canton Daily News by Frederic Gregory Hartswick, a graduate of the Sheffield Science School at Yale University. After a two year draft with the American Ambulance Field Service in France, Hartswick, a former editor at Judge, had found himself working features for the New York World. It was here that Hartswick honed his already considerable code-breaking skills, after being drafted in by the paper’s editor, John O’Hara Cosgrave to produce “a code that can’t be broken” for the groundbreaking expedition of the Norge Airship. This 16-man adventure to the North Pole was being supported financially by the North American Newspaper Alliance. The sharp, witty and deeply imaginative Hartswick was an expert in the Playfair Cipher, used in modern cryptic crossword puzzles and cryptograms — and also by the British Military during the war. The men on the voyage needed a way of disguising their messages that was relatively easy to code and decode. The Newspaper Alliance needed to ensure that their regular stream of updates would be ‘shrouded in an impenetrable mystery’. Hartswick was on hand to oblige. On March 29th 1926, the Italian-made airship was launched at a lavish ceremony presided over by fascist leader, Benito Mussolini in Rome on March 29 1926, at a ceremony at Ciampino aerodrome. The race to produce a code took place in January 1926, and it was during this same period that Hartswick encountered Brown.

On March 28 1926, the evening prior to the Norge’s launch, Brown’s remarkable story was published in the Washington Evening Star whose editor, Theodore W. Noyes had long been opining Mussolini’s “wise paternalism and greatness as a public statesman” (Washington Evening star, December 3 1925, p.6). The story’s appearance in the Canton Daily News in July was a later syndication.

On the surface of things, Brown’s story offered a fairly straightforward narrative. In January 1918 whilst serving as an aerial photographer for the British Royal Flying Corps he was arrested and charged under the Defence of the Realm Act for taking interior shots of a C6 Submarine under the command of his friend, Lieutenant General Roe at the Faslane Naval Base in Scotland. In January 1920, now recruited as Branch Secretary of the Comrades of the Great War in Glasgow, Brown was arrested in Hammersmith and questioned over the assault of Nurse Nightingale Shore after it was found that he matched the description of the man seen by the victim’s friend. Two years later in January 1922, he was charged by Police in Turkey; this time for the murder of a military officer. Brown had found employment as a photographer with a commission dispatched to Constantinople by the British and American Governments to record human rights abuses in Galata and Thrace. On each occasion, a representative of some authority or other would intervene and Brown would be released. The full article can be read below:

In relation to Toplis and the Etaples Mutiny, the fact that Ernest C. Brown was a Branch President of the Comrades of the Great War in Glasgow is an intriguing detail. Harry Fallows — the only person ever to place Toplis at the scene of the crime — talks about flashing his Comrades of the Great War membership card in his handwritten formal statement to Hampshire Police, despite only having completed a few months active military service (Harry Fallows Statement to Sergeant White, Hampshire Constabulary). Secondly, a genuine Etaples Mutineer, James Cullen — a founding member of the Communist Party of Great Britain — had his demobilization case taken up by Comrades of the Great War and discussed in Parliament by Winston Churchill. The man discussing Cullen’s case with Churchill was the organization’s founder — the ultra Conservative MP Wilfrid Ashley. Like Brown, Cullen was also from Glasgow.

Section D

As a member of the Anti-Socialist Union and the People’s League Party, Ashley was very closely aligned with Sir George Makgill, a mysterious early intelligence figure believed to have founded Section D, a ‘secret unity’ of Mi6 with close ties to the higher echelons of the British Conservative Party and Ashley’s anti-Trade Union movement. Extraordinarily, some 14 years prior to the attack on Nurse Shore, Charles Crossley, a senior representative of the Citizen’s National League — a forerunner of Makgill and Ashley’s Anti Socialist Union — featured in the death of Serge Gapon on a beach at Hastings, the resort on the South East coast of England where Florence was heading on the day she was attacked. The body of the powerfully-built Russian, said to be the brother of Socialist revolutionary, Father Georgy Gapon, was washed from a groyne at Hastings on Sunday 11th March 1906. A few weeks later the body of his brother — the man who had led Russia’s 1905 Revolution — was found hanged at a villa in Oserki, just outside St. Petersburg.

Charles Crossley, a visitor from London, had been seen talking to the man at the pier the previous evening. The man told them he was a captain in the Tsar’s Imperial Guard and on his way to visit the Russian Consul in Folkestone. An attempt to deport the man under the Aliens Act by magistrates in Eastbourne the week prior to his death had been unsuccessful, when the British Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone had declined to enforce the order. Crossley and his brother were the last men to see the Russian alive. Two days later, Crossley featured in another report, this time announcing the formation of an National Anti-Socialist League at the Junior Carlton Club in London’s Pall Mall. The meeting was held under the presidency of Thomas Orde Hastings Lees, Honorary Secretary of ‘prepper’ association, the National Service League. Among the League’s most active and influential members was Makgill’s friend, Sir Walter Long.

Section D, an offshoot of Makgill’s privately funded Industrial Intelligence Board (IBB) was tasked with flushing out the Soviet threat which was thought to have emerged in Working Mens’ Unions in post-Revolutionary Britain. Despite its links to the upper ranks of civil society, Section D’s methods were described as brutal and extreme even by those who used its services (Churchill’s intelligence man, Desmond Morton, head of Section V at Mi6, among them). Makgill was assisted in the project by ‘Room 40’ Playfair Cipher specialist, Sir Reginald Hall, the former director of British Naval Intelligence. Hall, Ashley and Makgill would subsequently join forces with Théodore Aubert, the Swiss lawyer who would defend White Emigré, Maurice Conradi, charged with murdering Soviet ambassador, Vatslav Vorovsky — possibly on the orders of Alexander Guchkov — in Switzerland in 1923.

Makgill keeps cropping up in many of the various threads I’ve been following and it’s worth noting that at the time of Florence’s death there were significant events taking place in Russia, where Florence’s brother, Brigadier General Offley Shore had been serving as British Attaché to the Tsar of Russia’s Imperial Forces in Tiflis (in modern day Georgia). Shore had remained at his headquarters as part of the Imperial network of spies and embassy staff until he was replaced by Colonel Geoffrey Davis Pike in spring 1918. A number of ministers within the British Foreign Office had been furious at Shore’s refusal to share intelligence with anyone other than the War Office. None was more concerned than Senior British diplomat, Sir Charles Marling who seemed determined to have Florence’s brother removed. A renewed Turkish offensive had threatened allied efforts to safeguard the Baltic territories of Transcaucasia against advances by Lenin’s Bolsheviks, the hardline revolutionaries looking to extend control of Southern Russia. Tiflis was fending off attacks from all sides: from the Turkish Army to the south of the city, and Lenin’s forces from the north.

At this time allied defences were being shored-up by a ragtag army of Armenian and Georgian nationalists who were demanding the immediate release of British-held funds controlled by Brigadier Shore to secure additional weaponry. The British Directorate of Military Intelligence had just signed-off on a plan devised by Oliver Locker Lampson to finance the Armenians using 20 million pounds sterling from funds held by Shore’s Mission at Tiflis. Despite being ordered to release them by Marling, Brigadier Shore, still head of the mission, stalled and refused to do so. In a telegram to the British Foreign Office dated December 21 1917, Marling complained that Shore was hesitating and urged the War Office to intervene (Marling Telegram to Foreign Office, 21 December 1917, F.O 371/3019, 241203/229217/17, 13 December 1917, F.O 371/3018).

As a response, Captain Edward Noel, a respected and perhaps more tractable member of the British Secret Service, was brought in by Marling in late December. According to Timothy C. Winegard, professor of history at Colorado Mesa University, Noel’s job was to monitor communications and ensure that all intelligence and funds were shared immediately whenever necessity demanded it and whatever the cost politically (The First World Oil War, Timothy C. Winegard, p.159-160). Protecting British and American interests in the Baku oilfields became priority number one (read: Michael Tillotson’s 2018 Times article).

Shore’s hesitation came at a staggering cost to Britain and Imperial Russia. The price paid by Armenia was greater still. Within weeks of Shore’s refusal to arm the Armenians through British held funds in Tiflis, over 2,500 Armenians and 20,000 Azerbaijanis lay dead. The Bolsheviks had seized control of Baku.

Marling was certainly no friend of the Bolsheviks. The triumph enjoyed by the Revolutionaries in removing Nicholas II was encountering a counter-challenge by Tsarist loyalists who had Britain’s full support. Marling’s plan was simple: remove Lenin and the Bolsheviks from power and restore the Russian monarchy under the leadership of his friend, the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich. Pavlovich, who had been exiled by the Tsar over the murder of Romanov confidant, Grigori Rasputin in 1916, had struck-up a close personal bond with Marling and both men regarded Brigadier Shore as an obstacle in attempts to restore a Tsarist regime. In their view, Shore and the War Cabinet’s refusal to recognize the urgency of arming the Armenians and the Georgians had considerably undermined the allied efforts and Churchill’s ‘secret war with Lenin’. Sadly, the man who replaced Nurse Shore’s brother Offley as the Head of the British Mission in Tiflis — Colonel Geoffrey Davis Pike — was murdered by Bolsheviks just eight months after his arrival. It is something of a tragic irony that he should have been born to a long serving military family at Lunsford Cross in Bexhill on Sea, where Nurse Shore was discovered unconscious in a third-class train carriage.

A Revenge Killing?

Just days before Florence Shore’s murder in January 1920, General Kolchak, the White Russian leader that Britain and America had been supporting against Lenin’s government of Bolshevist revolutionaries, was handed over to the Bolsheviks and brutally murdered. In the immediate aftermath of Russia’s October Revolution, a full scale civil war had erupted between the ‘Whites’ — supporters of the Tsar — and the ‘Reds’ — supporters of Vladimir Lenin. For two years the Whites were supported by allied forces, but the complete withdrawal of British troops in October 1919 and American troops the following January, would leave Kolchak and his troops exposed. As a result, the General had been forced to surrender. The exit route Britain had promised him had been removed too. Kolchak’s hopes of escaping across the border to the British Mission had been scuppered and his capture and execution marked a 360 degree turn in the coalition government’s relationship with the Soviet. Obliged by the terms of the peace treaty which came into effect on January 10th, just two days before Nurse Shore was attacked on the train, Lloyd George was preparing to talk trade with Lenin and ditch all prevailing military efforts to remove his Soviet government.

The man that Makgill and his people had been preparing as the Tsar’s replacement in Russia was none other than the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich — friend and ally of Sir Charles Marling who had been none too quietly backing the fresh Romanov bid for the throne. When news arrived of Kolchak’s capture and execution, Pavlovich was in exile in London. As first cousin to Rafaele Farina, a senior Russian Intelligence Officer at Mi5, it is possible that the attack on Florence could have been a revenge attack by White Russian Tsarist loyalists for the appalling betrayal of Kolchak and Imperial Russia.

During these same months, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich was just receiving word of the violent death of his stepbrother and other members of the Tsar’s extended family. Bolshevik guards had taken rifle butts to the heads of Prince Vladimir Paley Pavlovich, the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna and four other members of the once mighty Romanov family and left them for dead inside a mine-shaft. The injuries sustained during the attack were brutal and merciless. Reports of the incident suggest the injuries suffered by the royal victims were not unlike those of Florence.

Reporting the attack on Nurse Nightingale Shore on January 22 1920 , the Illustrated Police News painted a chilling scene. Florence had been found “disfigured, unconscious and soaked in blood from a gaping wound in the head”. “Outrage rather than robbery” was considered to be the motive.

Home Office pathologist Dr. Bernard Spilsbury recorded that Nurse Shore had received three separate blows to the head ‘possibly by a revolver butt’. One wound had passed completely through her scalp, a second revealed bone exposed beneath the wound, and a third showed a large fracture to the skull. Her injuries were every bit as horrific and every bit as emphatic as those inflicted on the Prince and his family. If the three blows had been dealt to subdue the victim during the commotion of a robbery, the level of violence was clearly disproportionate to the threat that someone of Florence’s age and stature would have presented.

The White Russian exiles in London and Paris were the first to feel the full bloody weight of being sold out by the allies; visas were obstructed, relief efforts undermined and the trappings of diplomatic privileges were to be stripped from them overnight.

The Bolsheviks may have taken their considerable wealth and properties but it was the Brits that had robbed them of hope — the only real resource the movement needed at this time.

Churchill, who had invested so much of his time, skill and reputation supporting the ‘Whites’ expelled a mighty sigh of resignation. He was powerless. Britain still had in excess of 2,000 troops in Russia, many of them prisoners. In his view, ‘all the harm and misery in Russia’ had arisen out of the wickedness and tyranny of the Bolsheviks. The policy he had always advocated was the ‘overthrow and destruction of that criminal régime’ (Churchill to the House of Commons, Manchester Evening News 19 November 1920, p.4). Despite the War Secretary’s protests, Prime Minister Lloyd George and the Cabinet had made their decision. The following February, Churchill was removed from the War Office, and Long was removed from the Admiralty. The Conservative-Liberal Alliance that had got Britain through the war was about to be well and truly shattered.

Is Ernest C. Brown’s Story credible?

Was Ernest C. Brown the regular man of mystery he makes out to be in the interview with the Canton Daily News? Well, despite some of the things Brown mentions being a little too difficult to verify at time of writing, the story he tells of his time with the Inter-Allied Commission in Turkey and being arrested for the murder of a Turkish Officer in Galata in November 1921 certainly chimes with real life events — and it is also directly linked to other real or imagined Soviet plots. The relative obscurity of the event and the fact it was published in a reputable title, also lessens the probability of outright invention.

Brown’s third and final arrest in Galata in January 1922 appears to have coincided with something called the ‘Harington Plot’, a tense diplomatic crisis that took place in Turkey between July and September 1921. The story centered around a Soviet-backed plot to assassinate General Charles Harington, the British Commander-in-Chief and Chairman of the Inter-Allied Commission. Galata at this time was dominated by refugees escaping the Bolshevik advance in Southern Russia. According to a report by the Sheffield Daily Telegraph in November 1921, the ‘best blood of Russia’ — the White Russians — had taken over the businesses and ‘dispossessed innumerable Turks and Greeks’. Russian was the predominant language and all the best restaurants and all of the shops seemed to be Russian. A Russian Generalissimo, the Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, now without arms, means or power, had even anchored his yacht there (Sheffield Daily Telegraph 03 November 1921, p.2).

“Now then Mr Brown — who are you and what are you? Suppose we take step over to Police Headquarters and talk it over.”

The Strange Case of Capt. Brown, Thrice Accused of Capital Crimes, Canton Daily News, August 1926

Brown claims to have arrived with the Inter-Allied Commission at a time when Thrace — then occupying a bottleneck region between Turkey and Bulgaria — was the subject of alleged massacres. According to eyewitnesses, the Turks had invaded the disputed area, massacred Greeks in the villages before looting from houses and committing all manner of horrors. According to The Daily Herald, Turkey had refused to accept the terms proposed at the London conference and was demanding the return of Thrace. The role of The Inter-Allied Commission was to try and unravel the tangle and restore peace. As a civilian staff photographer it was Brown’s job to provide visual evidence of the atrocities. Curiously, the murder of the Turkish officer for which Ernest C. Brown was subsequently arrested took place on November 11th — the day of the Armistice Day Ball at the British Embassy — the day that it was being reported that Turkish Nationalists in Adrianople were planning fresh raids on Thrace.

One man who may have had a significant impact on our arrival in the region was billionaire arms-dealer, Basil Zaharoff who had strong family links to Thrace and whose stakes in armaments manufacturer, Vickers had given him considerable leverage over Britain’s military capabilities and the reach and effectiveness of its secret service.

Curiously enough, Zaharoff was also one of the many curious passengers over the years to have boarded the Orient Express, whose real-life snowdrift stay in Thrace inspired the legendary novel.

Brown’s arrest in January the following year also just happened to coincide with the publication of a series of photos presenting the ‘Tragic Plight of Russian Refugees’ in the Turkish capital. The photographs were published in London’s The Graphic newspaper and appear to have been commissioned by Ariadna Tyrkova-Williams and Michael I. Rostovtzeff’s White Russian Refugee Relief Association operating from Fleet Street in England. After his stint with the Inter-Allied Commission, Brown had stayed and found a studio in Grand Rue de Perá, a street choked with refugees who now ambled aimless and shamefaced over its winding, desultory dust plains. According to reports, some 110,000 Russians had arrived in the city after General Wrangel’s defeat against Lenin’s strengthening forces in the Crimea. The White Russian Army had evacuated and landed here. The publication of these pictures would have been seen as a provocative move from the Brits, and Brown confesses in his interview that his earlier shots of Thrace ‘had not pleased the Turkish High Command’ (Canton Daily News Sunday, August 15, 1926, p.43)

Brown was duly hauled before General Refet Pasha (Refet Bele) at his HQ in Istanbul — chief architect of the Greek Genocide and by October that year, the newly appointed Governor of Thrace (Aberdeen Press and Journal 25 October 1922, p.6).

The plot against Harington, which proved to be unfounded, had been ‘unearthed’ by British Intelligence, or, as I think is far more likely, the men working for Sir George Makgill’s famously unmanageable and unaccountable, Industrial Intelligence Board. The so-called ‘Harington plot’ had centered around a scheme to spark a mutiny among Muslim troops serving as part of the British Imperial forces and then blame it on Lenin’s Bolsheviks (Arrests Constantinople, The Scotsman 22 September 1921). The desired outcome was that Britain would withdraw support for the Turkish Revolutionaries and revoke the Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement, signed in March 1921.

Curiously, among those leading questions about the plot in the British House of Commons was Comrades of the Great War founder and George Makgill ally, Colonel Wilfrid Ashley. 3

Reports in the press at the time hint at various reprisals and agent provocateurs and it’s certainly the case that a good number of arrests were made by Turkish police. Was Ernest C. Brown one of those arrested? Refet Pasha — the man who had Brown arrested for the murder of a Turkish officer — accused Liberal statesman, Damat Ferid Pasha, Andrew Ryan of the British Embassy and Sait Molla of the Friends of England Society, of devising the plot to derail ongoing trade negotiations between Britain, Turkey and Russia. Brown could certainly have been helping things along, especially if he’d been in the employ of Makgill and the Industrial Intelligence Board. 4

The final irony is that it was the Reading Room at the British Library that proved so central to Ernest Brown’s alibi. The room’s status in all manner of spy capers is legendary and his story regarding his alibi is confused to say the least. In the Canton Daily News article of 1926, Brown tells F. Gregory Hartswick that he was cleared of any involvement in the Shore Nightingale murder as a result of a time stamp on a Reading Room permit stub. However, in an interview he gives to the Sunday Post dated January 18th 1920, Brown claims he had been released solely on the word of a Reading Room attendant, who had some vague recollection of Brown visiting the room that week. Brown states unequivocally that the stub he had retained from his reading room session had NOT been dated (Mr Brown’s Alibi, Sunday Post, 18 January 1920, p.2). Sadly, Brown was released from custody on the very day that Shore succumbed to her injuries. Any chance of a positive ID from the victim was gone. Florence had died without regaining consciousness.

A Cousin at Mi5

As strange as it may seem, there is another dimension to this spy story that is every bit as intriguing. Perhaps more so.

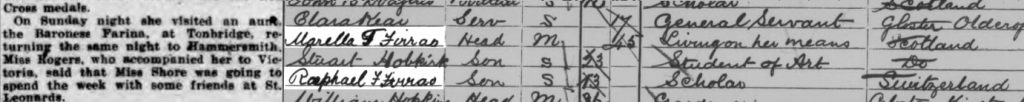

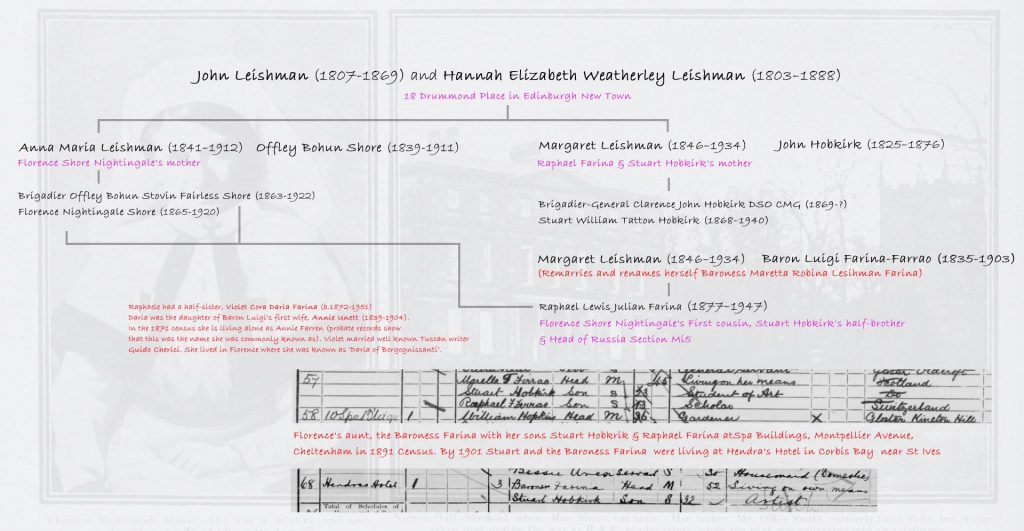

It transpires that Raffaele Farina, the first cousin of Nurse Nightingale Shore, was a senior British Intelligence officer. On Sunday 11th January, the night prior to the attack on the train, Florence had visited Raffaele’s mother in Tonbridge, an idyllic Tudor market town some 30 miles south of London. The Baroness Farina was Florence’s aunt on her mother’s side. The reason for her visit, which lasted some several hours, is not recorded.

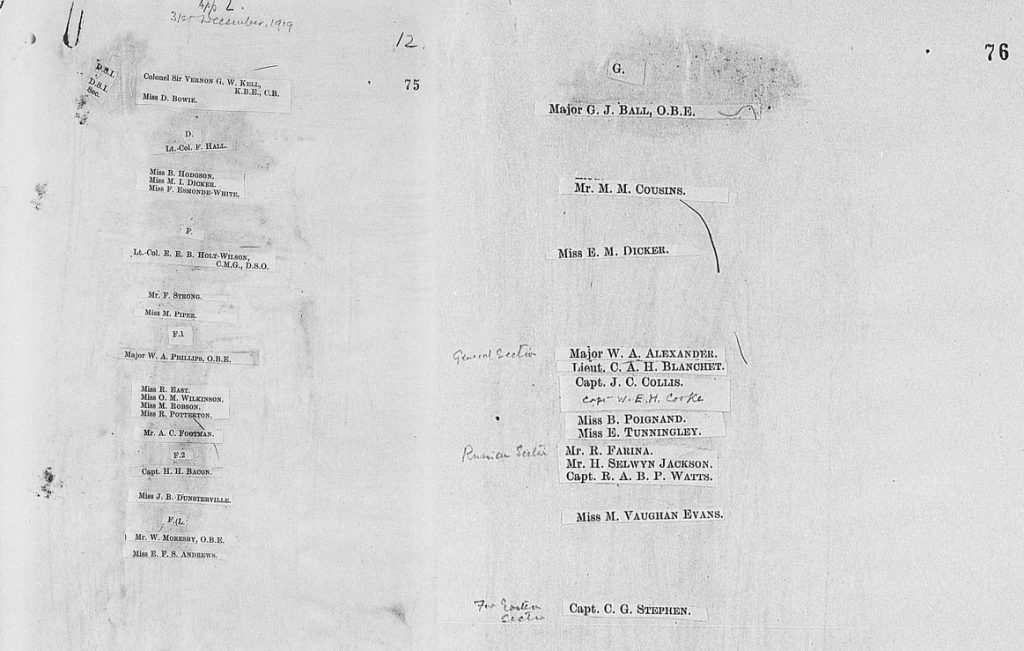

At the time of Florence’s death, Farina was serving on the 4th Floor at 4 Queen’s Gate under Major George Joseph Ball as Head of Mi5’s G4 Russian Section. Here he dealt with a regular flow of political exiles, revolutionaries and slippery agent provocateurs. Farina’s next post was Head of Station for Mi6 in Latvia, whose membership of the Russian Empire had collapsed with the 1917 Revolution.

From February 1921 to March 1931, Farina fronted the Passport Control desk in Riga, by far the most prolific of the Baltic Stations operating under Mi6. Here he would be responsible for collecting special intelligence relating to Latvia and Lithuania. Mi6 — or SiS as it was known in those days — had been intimately allied with the passport control system for years. His first boss in Riga was Reginald ‘Rex’ Leeper, previously employed by the Foreign Office at the Political Intelligence Department now serving as First Secretary of Legation from Valdemara iela 7. On Leeper’s departure to the News Department of the Foreign Office, Farina became attaché to Soviet-obsessive, Edward Hallett Carr. Between them Carr and Farina ran many of the British agents and sources within the Bolshevik regime in Moscow. Farina left the Riga desk in March 1931 when he was succeeded by Harold Gibson, but his ten-year tenure there was not without incident.

In 1924 Farina had been responsible for bringing the explosive Zinoviev Letter to the attention of Mi5 and Special Branch. The so-called ‘Red Letter’, marked ‘very secret’, provided instructions to British Communists to mobilise its forces within Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour Government in support of the Anglo-Soviet treaty. The treaty, which had endured years of tough negotiations, was due to be ratified within weeks of the General Election scheduled that October. The letter packed an additional punch; the success of any subsequent armed insurrection would require the cooperation of the armed-forces. Zinoviev’s message on this point was very clear: ‘agitation-propaganda’ was to be extended to the armed forces. When the green light for revolution was given, it would be “desirable to have cells in all the units of the troops, particularly among those quartered in the large centres of the country, and also among factories working on munitions and at military store depots” (Moscow Orders To Our Reds, Daily Mail, Saturday, Oct. 25, 1924)

The letter was signed on headed notepaper by Grigori Zinoviev, president of the Comintern, the Soviet International organisation.

On October 25, 1924, four days before the election, Lord Rothermere’s Daily Mail splashed the devastating headline across its front page: Civil War Plot by Socialists’ Masters: Moscow Orders To Our Reds; Great Plot Disclosed. MacDonald and the Labour Party lost by a landslide to Stanley Baldwin and the Conservatives.

But the letter wasn’t real. The letter had been faked.

A subsequent investigation by the British Foreign Office discovered that the ‘order to our Reds’ had been a clever and audacious counterfeit produced by an Intelligence source in Riga. Worse still, it had been Nurse Shore’s cousin Raffael Farina who had ensured that the letter had entered the intelligence system and been received safely into the hands of Mi5 controllers in London. Despite his apparent failures to ensure the integrity of human intelligence, Raffaele remained at the Mi6 desk in Riga for a further seven years. How was this so?

Either the contents of the Zinoviev Letter were known to be perfectly true, or known to be perfectly false; that’s how so. Farina was just doing his job. If some members of Mi6 were involved in a dirty-tricks campaign to derail the Anglo-Soviet Trade Treaty as was alleged, then the most likely scenario is that Farina had been under specific instruction to deposit the intelligence into the hands of Mi5 by his Mi6 superiors, Hugh Sinclair and Desmond Morton with the knowledge and cooperation of his Riga boss, Reginald ‘Rex’ Leeper, whose propaganda work for the Political Intelligence Department of the British Foreign Office was legendary.

To push home the likelihood of this, it’s worth pointing out that Leeper took up his role as Chief of the British Legation alongside Farina on September 22nd 1924. The incriminating letter that had been passed to Farina’s desk was dated September 15th 1920 , the week prior to Leeper’s arrival. A report and translation had been compiled by Farina in Riga on October 2nd and on October 9th a decoded telegram was received at SiS headquarters in London. It was duly handed on to Joseph Ball, W.B. Findlay (one of Makgill’s men) and Churchill’s trusted aides, Desmond Morton and Hugh Sinclair. With Leeper at the helm, the letter (which might otherwise have been dismissed) was spared many of the usual rigorous protocols of Intelligence screening and analysis in Riga and was eventually leaked to a reporter of the Daily Mail. The most likely route was through Farina’s ex-Mi5 section chief, Sir Joseph Ball, who several years later would ditch his desk-job at Mi5 for a plum role in the Propaganda Department at Conservative Party Central Office. Either way, it was all carried out within weeks of Leeper taking up the post in Riga.

Farina kept his job because he was simply following orders.

But what was Farina’s relationship to the Nightingale Shores? What were the familial connections? If you’ve read Rosemary Cook’s excellent book on the Nurse Nightingale Shore murder then you will have come across some of these names already.

The Farina and Hobkirk Families

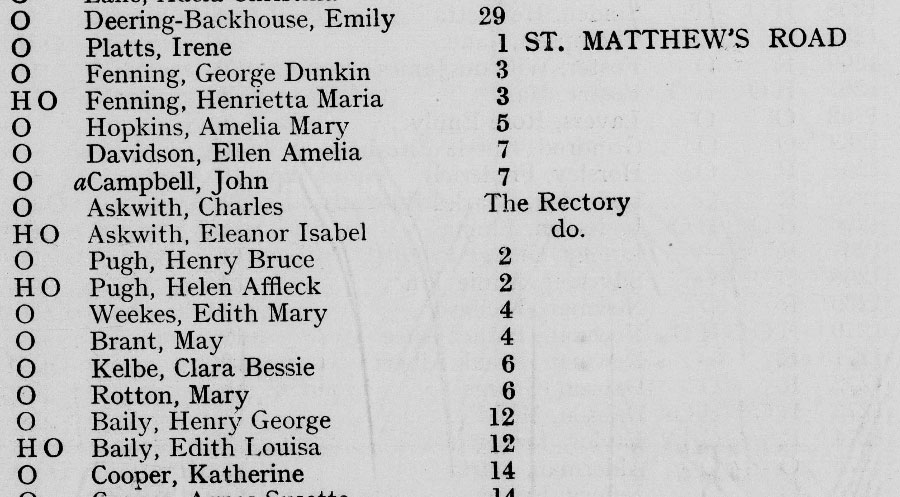

Raffaele Farina was the half-brother of Offley and Florence’s cousin, Brigadier Clarence John Hobkirk, another member of the family who pursued a long and distinguished military career, serving first with the Essex Regiment and then as Britain’s Military Attaché in Rome during the war. After sustaining an injury, Clarence was declared medically unfit and was retired from active service shortly after Florence’s death in 1920. As you might recall from Cook’s book, it was Clarence who acted as executor in both Florence and Offley’s wills. On their deaths in 1920 and 1922, the sister and her brother had left large sums in securities to be paid to Clarence and his brother, the landscape artist and figure painter, Stuart William Tatton Hobkirk. Florence also left Stuart the pendant that Police had falsely assumed to be missing. By 1924 Stuart was living at 16 Church Road, St Leonards — just a two-minute walk from Warrior Square Station, where Florence had due to to meet friends on the day she was attacked.

If Florence had bequeathed anything to their brother, Raffaele it’s certainly not recorded.

Born in Switzerland in 1877, Raffaele Lewis Julian Farina was the son of Italian exile, Baron Luigi Farina and Margaret Leishman — subsequently restyled the ‘Baroness Maretta Robina Farina Firras’ — sister of Nurse Nightingale Shore’s mother, Anna Marie Leishman of 18 Drummond Place in Edinburgh New Town. Luigi was her second husband. Margaret’s first husband, John Hobkirk, the father of her two boys Stuart and Clarence, had died shortly before her marriage to Luigi in Rome in 1878. Reports in the British Press suggest that Luigi Farina, who had once been dragged into a disreputable spat in Germany with Henry Labouchère Liberal MP, was one of an illustrious stream of visitors conveying his wishes to General Garibaldi at Stafford House during the Italian revolutionary’s one and only visit to England as the guest of the Duke of Devonshire (London Evening Standard 14 April 1864, p.3).

During this period, the fortunes of the Nightingale Shore family were taking a nosedive. The Shore’s had returned from a tour of Dresden and Holstein to news of a massive loss of shares in the family stake-holdings. By 1878, Florence’s father Offley had accrued debts of over £100,000 and was facing bankruptcy. It wasn’t the first time and it wouldn’t be the last. In October 1879, it was announced that Colonial Trusts Corporation Ltd, which had controlled the family’s stakes in the Midland Railway Company of Canada and various collieries around the globe, was being wound down after a two year investigation.

Luigi Farina’s fortunes were no less serious. He had arrived in England in 1860, the year in which his father, Baron Raffaele Farina had been expelled from Naples for taking part in the so-called ‘Count d’Aquila Conspiracy’. According to the press of the period, it appears that Luigi’s father, the newly appointed Prefect of Police, had conspired with Prince Louis to depose the Spanish Bourbon King of Naples, Francis II in advance of General Garibaldi’s arrival. The plot — which was as vague then as it is now — was to then scuttle the ship carrying Garibaldi — the great ‘liberator’ of the revolution — before he and his army could ever set foot in the capital and reunite the divided Italy. Within days of the alleged plot being exposed, the Prince and his fellow conspirators had fled to France and then to England, their land and properties confiscated.

As Churchill may have said: it was a riddle inside a mystery inside a coup d’etat — wrapped-up in a revolution.

Raffaele Farina … Spycatcher

Cousin Raffaele had begun his Secret Service career at the Ministry of Information, a post that had taken him as far away from his hands-on science career as he could get. Graduating with a 1st in ‘Assaying’ from Camborne Mining School in 1899, Farina had spent the first years of his adult working life as a mining engineer for Orsk Gold Mines before being recruited into a notorious investment scandal featuring Lord Derby, Lord Knollys and senior members of the Royal Household. Formed in 1905, the Siberian Proprietary Mines had only weak concessions to mine gold, and within two short years its shares had collapsed. Timely buying and selling, however, ensured that its senior shareholders profited handsomely from the scheme. The company would subsequently become another casualty of the Russian revolution. Prior to this engagement, Farina had been in the employ of the Transbaikalian Gold Mines of the Altai Mountains in Siberia. His reports for the Institute of Mining and Metallurgy described gold veins of varying quality. Some were ‘porous, friable and highly oxidised’, whilst others were of the ‘hard white quartz type’ (Nature, Nature Publishing Group, February 22 1906, p.398). Despite his freedom to travel, Farina wasn’t footloose and fancy-free. In 1903, he had married Isabel Anna Baird Smith, the granddaughter of Richard Baird Smith, the Chief Engineer of the East India Company and hero of the Siege of Delhi and the Indian Mutiny.

In 1914, Farina was on his way to the Caucasus, a mountainous yet mineral rich region extending over Russia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. (Mining Magazine, Volume 11, 1914, p.355). His Russian language skills had earned him the responsibility of managing much of the underground work of the Caucasus Copper Company in the Batumi region of Georgia, an area that was constantly under threat of Turkish invasion. He returned to England in 1915. A congenital issue with his leg saw him declined entry into active service and he was enrolled into the Department of Information, responsible for publicity and propaganda. Eventually, Farina’s knowledge-base and language skills would bring him to the attention of Mi5 and it is here that his story begins in earnest.

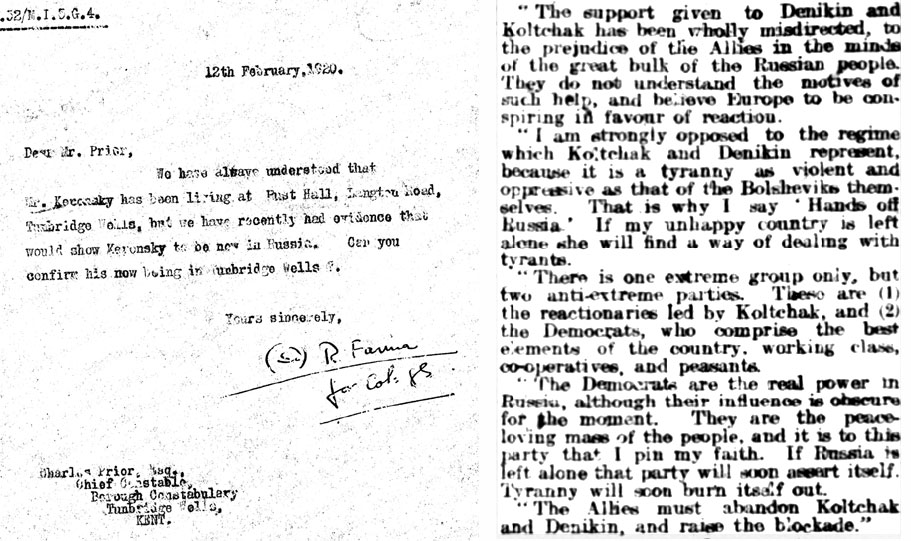

The type-written letter in the picture below sees Desmond Morton of Mi6 discussing the formation of Krassin’s All Russian Co-operative Society with Florence’s cousin in October 1920. Other files indicate that Farina was working at the Russian Section of Mi5 as early as August 1918, when he was attached to G4 branch, a small but rapidly expanding team of four officers and four secretaries tasked with putting together a blacklist of Russian émigrés (KV 2/568 – KV 1/44, National Archives). Farina wasn’t to know at this stage that several of these émigrés were just yards from where his cousin Nurse Shore was heading on the day she was attacked.

Extraordinarily enough, another tight skulk of crepuscular Russian exiles were also in the vicinity of Farina’s mother back in Tonbridge, the aunt that Florence had visited on the afternoon and evening prior to the attack. It is it possible that Florence was followed from Baroness Farina’s house in Tonbridge back to London? And from London to St Leonards on Sea? Had Rafaele Farina’s prominent security role made Florence a vulnerable target and was he there on the afternoon of her visit?

Baroness Farina

Shortly after 12.30 on the afternoon of Sunday January 11th, 24-hours before the assault on the train, Florence had visited Raffaele’s mother, the Baroness Farina at her home at 88 Hadlow Road in Tonbridge, some 30 miles south of London. The Baroness was her aunt on her mothers side and had been maintaining the not-altogether legitimate title of ‘Baroness’ ever since her marriage to Raffaele’s curiously footloose father, Luigi.

Even though her friend Mabel Rogers claims that Florence knew of her trip to visit friends in St Leonards on Sea some days in advance, Florence didn’t continue to the resort after visiting Tonbridge. Instead, that same Sunday evening, Florence took the 7.30 train back to London, before setting off again on the Monday for St Leonards. It’s an unusual move in the circumstances, as Tonbridge was already more than half-way to St Leonards on Sea. The Hastings Line operated by the LB & SC Railway Company linked London and Hastings via Tonbridge, Lewes and Bexhill. I think many would agree that it would have saved time, energy and money for Florence to have travelled from Tonbridge to St Leonards on that same Sunday evening or to have stayed at her aunt’s house overnight and to have grabbed a head start the following day. What was so important that she first had go back to London? And what was so important that she first had to visit the Baroness?

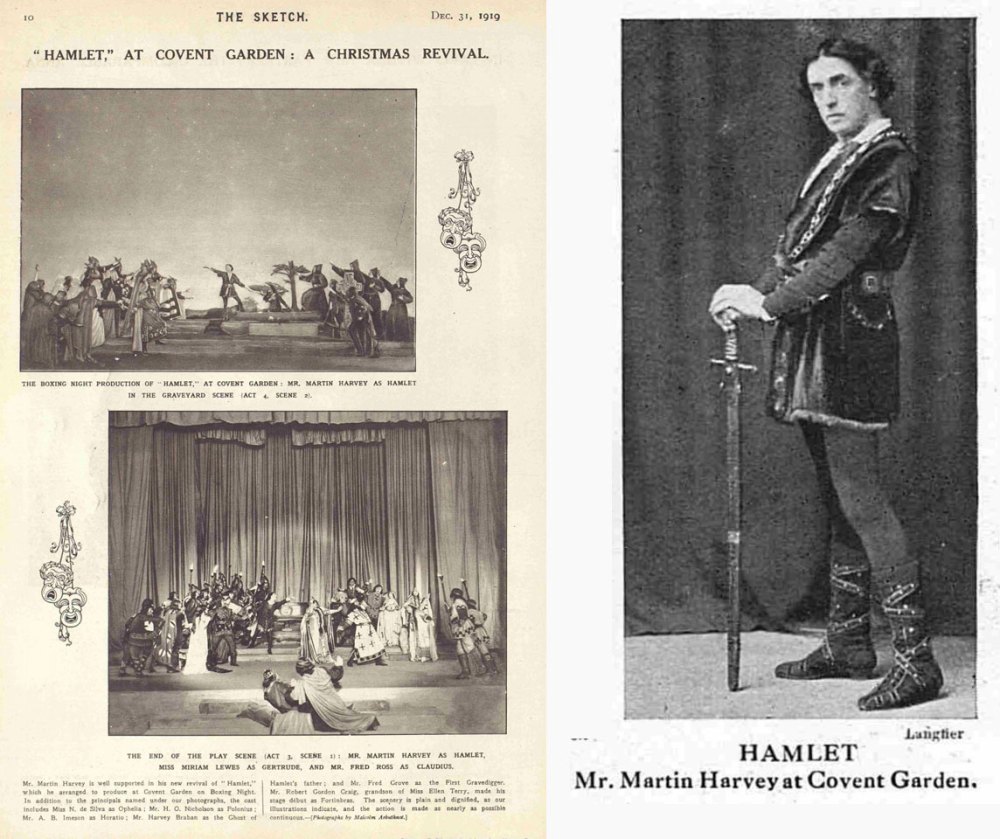

The coroner at the inquest into Florence’s death also quizzed Mabel on her unexpected stop at Tonbridge. On the night of Monday January 12th, Mabel had been sitting in a theatre in Covent Garden when she learned of the attack. The production being performed, ironically enough, was Shakespeare’s blood-thirsty revenge tragedy, Hamlet with Sir John Martin-Harvey reprising his role as the grievous Prince and Frederick Ross as his father’s ghost. A tap on Mabel’s shoulder during the interval was followed by some shocking news; Florence had been attacked and lay in a coma. Mabel had made her way to the hospital in Hastings but in a statement she made at the inquest, she claims she was only able to get as far as Tonbridge Station. Mabel — superintendent of the Carnforth Lodge Nursing Home in Hammersmith, London — had left on the 11.20 pm train from London and disembarked in Tonbridge at 12.00 am. She arrived at the hospital in Hastings some three hours later. The entire journey that Florence would take to Hastings would have lasted around two-hours twenty minutes in total, so arriving at the half way point in Tonbridge should have taken about one hour and ten minutes at the very most (at some point in the 1920s there was 90-minute route between London and Hastings).

Did Mabel meet with Baroness Farina prior to ‘motoring’ to the hospital?

At the inquest it was not clear why Mabel could only get as far as Tonbridge before managing to ‘motor on’. Did Mabel have to wait more than an hour for a connection? The train from Victoria Station that Florence Shore had taken earlier in the day was a direct connection to Hastings. Surely the night-duty staff at the ticket office would have warned her. Did Mabel ‘motor on’ to Hastings accompanied by the Baroness in a car? And if so why? When the train would evidently have been the quicker option for both of them? Mabel’s statement at the inquest is a little short on detail.

‘I caught the 11.20 train but found I could only get as far as Tonbridge and motored on.’

Mabel Rogers describing her journey to the hospital at the Inquest

You stayed there the night, I suppose?’

‘No, I motored on’

What time did you get (to Hastings)?

‘About 3 o’clock’

According to the Daily Herald, Scotland Yard were also exploring the possibility that the assailant had jumped off the train at Lewes and boarded another train standing in the station bound for Tonbridge (Daily Herald 16 January 1920, p.1). It’s a minor point but worth mentioning.

The Tonbridge Circle

Within twelve months of Baroness Farina arriving at 88 Hadlow Road, the former Russian representative to Paris and Berlin, Lt. General Sergei Belosselsky Belozersky arrived with his American-born wife, Susan — daughter of American Civil War Hero, Charles A. Whittier — at 20 Hadlow Road, just 200 yards from the Baroness. Both parties were still on Hadlow Road in August 1921 when news of an imminent breakthrough in the Nurse Shore Nightingale mystery was published in the local newspaper. A ‘certain’ Chief Detective Inspector who specialised in murder cases had made a statement to a Sunday journal that ‘developments of a sensational character’ would shortly be announced (Nurse Shore, Baroness Farina, Sevenoaks Chronicle, August 1921).

Sadly, no such announcement was ever made.

There’s little doubt that the Russian would have been under close observation by Farina and his team. This was a high-value Russian asset, and friendly or not, his activities locally and abroad would have been treated with the utmost gravity. According to letters and communications in the Churchill Archives, Churchill had been in regular contact with Belozersky during the closing stages of the Russian Civil War, where Sergey served as adviser to General Yudenich, commander of the Northwestern White Army.

The story of the couple’s arrival in Tonbridge and their work for the Russian Relief program was covered in the Sevenoaks Chronicle the following year. Some ten years later, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, the man Sir Charles Marling and Britain had been grooming as the Tsar’s replacement, would attend Susan’s funeral at Tonbridge Parish Church (Kent & Sussex Courier 14 December 1934, p.15). Just twenty years previously, the Canton Daily News had run a story of Dmitri’s ‘infatuation’ with Susan. The Tsar is alleged to have punished Dmitri by sending him on a six-month ‘sabbatical’ in Egypt.

In December 1929, another funeral took place, this time for the 28 year-old wife of Oliver Locker-Lampson, the former British military commander who had served as the Ministry of Information’s representative in Russia. It was Locker-Lampson who had devised the plot to arm the Armenians against the marauding Bolshevik advance. And it had been the hesitation of Nurse Shore’s brother Offley, that had prevented the plot’s success.

Oliver, who at one had lived at Robertson Terrace in Hastings, was an old intelligence colleague of Reginald ‘Rex’ Leeper — Farina’s first boss in Riga. Leeper’s department had acted as liaison between the British Foreign Office and the Secret Intelligence Service in Russia during and shortly after the 1917 Revolution. Years later it was alleged that Oliver’s Armoured Car Division had been complicit in a Guchkov-funded attempt to remove Prime Minister Kerensky from power by the leader’s military commander, General Kornilov. Kornilov denied the accusations. His attempt to wrest control was merely a desire to “strengthen the hands” of of Kerensky’s Provisional Government in carrying out its administration and to restore the rule of law over a quickly fragmenting military. It was not, he insisted, an attempt to restore the Romanovs but a way of preventing the return of Vladimir Lenin and a catastrophic maximalist power grab. Despite his protests, several Romanov heirs were arrested — among them Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich.

Oliver Locker-Lampson’s experiences in the region in the immediate aftermath of the revolution made him a fierce anti-Bolshevik, and his mammoth twenty year stint as MP for Birmingham Handsworth is marked by a regular schedule of anti-Communist protests and praise for the fascist movements of Hitler and Mussolini. Consoling him at his wife’s memorial that day was his old friend, Sergei Belosselsky Belozersky of 20 Hadlow Road. Oliver’s wife had become a regular attendee of the Russian Church on Buckingham Palace Road, and an uplifting service in Russian and English had been organized by her husband. Captain Alexander Soldatenkov, former secretary of the Imperial Russian Embassy in London also attended (Daily Mail, Dec. 31, 1929).

A few years later, Locker-Lampson gave evidence before Justice Avory in a libel action case brought by Princess Irina Alexandrovna against MGM pictures, who had portrayed her — inaccurately, or so it was claimed — as one of Rasputin’s lovers. Commander Locker-Lampson stunned the court with not one but two claims: the first that he had been involved in a plot to save the Tsar and his family, and the second, that he had been personally invited to murder Rasputin by the ultra-nationalist monarchist, Vladimir Purishkevich (Dundee Evening Telegraph, 02 March 1934).

In a deeply ironic twist, Oliver’s cousin Miles Lampson, former British Ambassador to Hong Kong and Egypt, would die at the very same East Sussex Hospital in Hastings as Florence Nightingale Shore.

Russians In St Leonards

If the arrival of a semi-invisible cadre of Russian exiles in Tonbridge wasn’t enough — given what we now know about about Farina’s position at Mi5 — then the fact that they had also taken up positions in St Leonards on Sea, makes Florence’s journey there in the first two weeks of January all the more unusual. More perplexing still, is that these same individuals had already appeared on Farina’s radar.

It transpires that in June 1920, shortly after the murder of Florence en-route to St Leonards, Farina was making follow-up enquiries to Hastings Police about several mysterious Russians living at an address in St Leonards on Sea. After liaising with Hastings Police, Farina learned that one of the Russians residing at the address was a prominent White Russian called Count Paul Ignatieff, the last Tsarist Minister of Education and a close friend of the murdered Tsar, Nicholas II. The Count had served as a member of the Provisional Government shortly after the Tsar’s abdication on March 5th 1917. Ignatieff had warned of the dangers of dismissing the first Duma of 1906. As an alternative he had recommended reviving an old form of parliamentary representation evolved from the local government schemes of the Zemstvos. The Tsar’s replacement, Prime Minister Kerensky rewarded the Count’s commitment to social and political reform by making him head of the Russian Red Cross, a role that would eventually bring him into contact with various Western figures looking to reconstruct and rehabilitate Russia in their own progressive image.

The wife of his cousin in Paris, Count Aleksei Ignatiev, had already made inroads here and was well liked in English circles. Like Florence, at the outset of the war the Countess had found herself assisting the French Red Cross, the family having already made the acquaintance of Dr Alexander MacDonald Westwater of Edinburgh Royal Infirmary whilst assisting the Red Cross in China. After the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917, the Count had narrowly escaped execution and was forced to flee Russia with his family.

The address at the centre of Farina’s enquiries was Woodmancote — a private nursing home on Woodlands Road in the Silverhill district of St Leonards, about a fifteen minute walk from Warrior Square Station where Florence was due to arrive.

According to the KV2 files at the National Archives, some of the correspondence intercepted by Mi5 suggests the Count was spending much of his time between France and Turkey, the country of his birth. This is interesting in light of Ernest C. Brown’s claim that just twelve months after being quizzed about the murder of Florence Nightingale Shore, he was arrested on murder and espionage charges in Constantinople, the Turkish capital.

The Ignatieff family’s association with Turkey was strong. Paul had been born to Count Nikolay Ignatieff, an aggressive, ultra-Conservative militarist who had previously served as Aide de Camp to the Romanovs and as Ambassador in Constantinople during the years 1864-1877 5. At the Constantinople Conference of 1876, some 45 years earlier, Lord Salisbury and the Count’s father, General Nikolay Ignatieff had walked arm-in-arm down the tortuous Rue da Pera in the European Quarter of Constantinople discussing the international issues of the day. Curiously, Ernest C. Brown found himself walking down these same streets in 1921 when he joined the Inter-Allied Commission.

In 1919, Count Paul made an application to the former Vice Consul of Russia in London Ernest Gambs, to relocate from Paris to England. The Count was making tentative enquiries into buying the nearby Tilekiln dairy. In the KV2 files there is a letter dated September 1919 in which Raffaele Farina apologises for not being able to help the Count secure British visas for Prince Boris Vassilitchikoff and his family in Paris. However, by July 1919 Farina can be seen informing the Ignatieffs of the Home Office decision to issue visas to all his immediate family members, including his five children and brother Nicholas. His brother Alexis was not so lucky. A rather terse note dated July 15 1919 states simply that Colonel Count Paul Alexis Ignatieff was ‘probably’ the subject of an Mi5 Blacklist, No.12489.

On the face of things, it looked like something out of The Thirty Nine Steps; decorated World War I heroine and sister of Brigadier General is murdered on her way to a quiet seaside resort currently under the scrutiny of her Mi5 cousin for harbouring high-value Russian assets and possible enemies of the state. All it needed was a German u-boat turning up at Glyne Gap Beach and Christie’s Colonel Race bounding across the sand flats of St Leonards waving a railway timetable.

To add another layer of intrigue, it was Baroness Farina — Rafaele’s mother — who was one of the first to visit the hospital. The Baroness had arrived within hours of Mabel and seized immediate control of the narrative as the press mob descended on Hastings. The press conference began with a series of candid interviews. “I cannot think of any motive for the attack other than robbery” she speculated, before bearing tribute to Florence’s “self-sacrificing life”, her life-threatening injuries and the disappearance of several items of expensive jewellery (Leeds Mercury 15 January 1920, page.9). Her account differed from the statements made by the first witnesses in several respects. Interviewed by the London Observer on Friday 15th January, the Baroness claimed the cases she had been travelling with had been broken open and all the valuables stolen. Her account differed from the statements made by the first witnesses in several respects. Interviewed by the London Observer on Friday 15th January, the Baroness claimed the cases she had been travelling with had been broken open and all the valuables stolen. However, the earliest newspaper reports describe how the cases ‘were apparently as originally placed’ and her hat was still placed on top of one of the portmanteau boxes. [The Nightingale Shore Murder, Death of a World War One Heroine, Troubadour Publishing, Rosemary Cook, p.172] This was supported by the platelayers who were the first to discovered the body when they entered the carriage at Polegate. The workers said there were no signs of resistance and the only indication of a struggle were a pair of broken glasses that lay on the floor of the compartment. The fact the newspapers also reported the presence of ‘the man in the brown suit’ suggests that the press had received this information from Police, as the only eyewitness to any of this was Mabel, now glued to Florence’s bedside in hospital. The men also reported the ‘open book’ that still lay in Florence’s lap, contradicting any suggestion of a violent struggle. There was blood evidence on the seat where she sat but nowhere else in the carriage. In fact “everything about the carriage seemed to be in perfect order”.

The Baroness also claimed to have warned her niece against sitting alone in an empty carriage: “Miss Shore visited me on three or four occasions; and the last time, strange to say, I cautioned her about travelling alone … how I do wish she had taken my advice.” In Christie’s novels it isn’t uncommon to find the lead suspect trying to direct the course of an enquiry by leaving trails of dubious intent. There had been a long-standing tradition in detective novels to have the narrator portrayed as the most trustworthy character; the detective’s right-hand man. Christie’s 1926 novel, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd totally trashed that trend when Poirot revealed that the murderer was none other than his most trusted assistant, Dr James Sheppard — the man giving all the nudges, the man leaving all the clues.

Despite the claims made by Baroness Farina, no items of jewellrey, it transpired, were missing. All were eventually accounted for.

Who Was ‘Goutchkov’?

It’s an extraordinary proposition; Florence Nightingale Shore, the first-cousin of Mi5’s Head of Russian Section was brutally murdered on her way to a prosperous British seaside resort that may have been harbouring enemies of the state. But what had led Mi5 to this discovery?

The file relating to Count Ignatieff — and extracted by Rafaele Farina on June 29th 1920 for his enquiry into Woodmancote nursing home in St Leonards on Sea — derived from a Personal File on someone by the name of ‘Goutchkov’ (File PF/R2670). This basically means that the Woodmancote nursing home address is likely to have been found in communications between ‘Goutchkov’ and a person of interest. The ‘Goutchkov’ the extract refers to is General Alexander I. Guchkov (often spelled Guchkoff). This was the same Alexander I. Guchkov who is alleged to have financed the coup d’etat against Kerensky and the assassination of the Soviet Ambassador, Vatslav Vorovsky.

A former banker and mercenary who had fought on a voluntary basis for General Smuts against the English in the Second Boer War, Guchkov became Minister of War for Kerensky’s Provisional Government after the February Revolution in Russia. He also headed Russia’s Red Cross in Germany.

After the triumph of Lenin and the Bolsheviks in Russia’s second October Revolution, Guchkov, like Count Ignatieff, found himself living in exile, settling first in France and then Berlin. Despite this he remained active militarily and politically. From his bases in France and Berlin, Guchkov became personally responsible for the funding of the counter revolution launched by Generals Deniken, Yudenich and Kolchak. After Kolchak’s defeat and execution in January 1920, Guchkov became the chief protagonist in a web of intricate conspiracies to retain the support of White Russia’s British and American allies. He was also at the centre of plots to bring down Lenin and the Bolsheviks. However, the Guchkov Circle’s links to General Bredow of the German Army, and to German Military Intelligence polarized him from the Ignatieffs whose refusal to release funds to Yudenich and Kolchack had contributed to their defeat (Sovietism is Anchored Russian Soul, Indiana Evening Gazette, 23 April 1921). Word on the ground in Britain and America was that the White Russian movement would trade with Germany once it had triumphed over the Reds.

Naturally, Britain wanted to beat Germany and her allies to those trading opportunities.

If any one, single person was in a position of sending a message out to Britain over the capture of General Kolchack the week prior to the attack on Florence, it was Guchkov. His daughter Vera, who married Scottish linguist Robert Traill, eventually became a member of the KGB. In 1975, Vera is alleged to have told the US State Department’s, William Gleason that her father had financed the assassination of Soviet Commissar Vorovsky in Geneva in 1923. Supported by ‘Ace of Spies’ Sidney Reilly, Guchkov is also believed to have funded other anti-Soviet plots. These may well have included the Zinoviev Letter in which Florence’s cousin, Raffaele Farina featured, the fake ‘Harington plot’ in Constantinople and the murder of Florence Nightingale Shore. Guchkov had the means, he had the motive and the funds necessary to carry it out.

Why would Guchkov do this? Maybe in an attempt to frame left-wing anarchists and subversives (like the Bolsheviks or Kerensky) and gain the sympathy and support of British Intelligence services. Or maybe it was an act of revenge for the failures of Florence’s brother Offley and the capture and execution of his good friend General Kolchak. One look at other press headlines at the time of the attack on Shore bears testimony to the analogous nature of developments in Russia. Alongside the headline, ‘Who Attacked Nurse Shore’ on page seven of The Daily Mail on Thursday January 15th, was the sensational and almost defeaning: ‘Plans To Overthrow Civilisation: Peril of Bolshevist Advances’. The outlook was just as ominous elsewhere. On the left of ‘Attacked On a Train’ report in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph the very same day, was the story of Kolchak’s disappearance and the collapse of White Russian forces. Worse still, news was now arriving that Lloyd George’s coalition government was considering lifting the blockades on Russia and opening trade negotiations with Lenin. This plan of ‘reconciliation with the Soviets’ would have dealt a considerable blow to Guchkov. The framework that allowed these discussions to take place had come into effect just 48 hours prior to the attack on Nurse Nightingale Shore. The ratification of the Treaty of Versailles took place on January 10 1920, and on January 16 1920, the Allied Supreme Council met in Paris to announce the resumption of trade with Russia that would allow the exchange of goods. White Russia had been betrayed; the millions of Russian lives lost fighting on behalf of the allies had meant nothing to the British. The Whites had triumphed over Germany only to lose their place in the world. It was a truly shoddy state of affairs.

Ignatieff featured in several other Guchkov intercepts over the years. In 1934, Mi5 intercepted a letter between Guchkov and Anatole Vasilievitch Baikaloff — a former member of the Revolutionary Socialist Party who British Intelligence would later come to regard as a possible Nazi-sympathizer. Guchkov was advising Baikaloff — an associate of former Prime Minister Kerensky — that his fiend Dr. Ewald Armende, should get in touch with Ignatieff in Canada (KV 2/2407).

Remarkably though, whilst Guchkov features prominently in Baikaloff’s Mi5 security file, Guchkov’s own security file — PF/R2670 — has never been made available.

The Zinoviev Letter, in which Farina had played a central role, was similarly inspired by White Russian and Conservative plans to scupper trade negotiations with Soviet Russia. Besides Farina, it later transpired that the key players in the drama included Conrad Donald Im Thurn — a former associate of Farina’s at Mi5 — Jim Finney, another employee of Sir George Makgill and several White Russian extremists linked to the deeply mysterious, Bratstvo Russkoi Pravdy, a dedicated brotherhood of émigrés launching a counter-revolution from Berlin. Those investigated and charged over the forgery included former Russian Ambassador to Paris, Vladamir Pavolich Orlov, Alexander Gumansky, Boris Kadomtsev and Alexis Bellegarde (Red Letter Sensation: Forged in Riga, Daily Herald 25 March 1929).

When authors Oleg N. Carev, Nigel West and Oleg Tsaryov trawled through the KGB Archives they found a file that implicated Guchkov in the scheme. In a report dated November 11th 1924, the KGB’s Berlin Rezidentura (Foreign Embassy) sent a report to Artour Artouzov and Genrikh Yagoda of Russia’s Secret Police which asserted that the letter had been “fabricated in Riga by Lieutenant (Ivan) Pokrovsky — who worked with Biskupsy, connected to Guchkov” (The Crown Jewels: The British Secrets at the Heart of the KGB Archive, p.40). The findings of Russia’s Secret Police would eventually chime with those of Germany and Britain; the letter had been fabricated in Riga by the White Guards Intelligence Organization featuring Pokrovsky, Orlov and Gumansky.

As far as murder motives go, there is however, a third option, a good deal more complex, and every bit as cunning.

Prime Minister Kerensky in Tonbridge

At the time that he was looking into Count Ignatieff and the nursing home at St Leonards on Sea, Nurse Nightingale Shore’s cousin at Mi5, Rafaele Farina, was making simultaneous enquiries about another Russian official, Alexander Kerensky at Tonbridge — the temporary home of Farina’s mother, the Baroness.

Florence at this time had just been demobilised, moving from the nurses hostel in Boulogne in October 1919, to the Hammersmith and Fulham Nursing Association based at Carnforth Lodge sometime in November. It’s highly unlikely that Florence knew anything of her cousin’s Mi5 enquiries, much less the activities of mysterious emigrés like Kerensky, who just two years previously had been the most powerful man in Russia.

Nevertheless, the once most powerful man in Russia could now be found crashing over at a friends’ house, just a few miles from Shore’s aunt. The threats and the dangers that Florence thought she had left abroad were emerging now as shadows much closer to home.

The Files KV 2/658 and 2/659 at the National Archives in London feature a letter written by Farina to Chief Constable Charles Prior asking for confirmation of Kerensky taking up residence at Rust Hall off Langton Road — the home of Near East expert and author, Simon Henry Leeder. Travelling from Constantinople sometime winter 1919, Kerensky’s first known address in England had been Connaught House, 9 Montague Street, opposite the British Museum in Russell Square (KV2/659). After liaising with the Divisional Superintendent in Tonbridge, Chief Prior confirmed that Kerensky was still in residence at Rust Hall but was shuttling regularly between Tonbridge and London.

In many ways, Tonbridge was an unusual place to stay. Author Stephen Gary once described it as a small town set in quiet fields of “mustard and apples, hops and wheat” ensconced by instantly recognizable oast houses. The grinding motor of political machinations that whirred out from the city were absorbed by its teeming avenues of neatly kept shrubs and hedgerows. This was no place to court excitement. But for Kerensky, still in-hiding, it was out of harms way and would have suited his typically agrarian Socialist sensibilities.

Kerensky, who had served as Prime Minister in Russia’s provisional government for little more than five months, was there with his close-friend and interpreter, Dr. Jakob Osip Gavronsky, who had represented the Kerensky government in London. The doctor’s Regent’s Park address — 7 Cambridge Terrace — would also provide Kerensky with a more convenient central London base.

Who is Kerensky?

Like Guchkov, Kerensky had played a critical role in the formation of a government in the aftermath of Russia’s February Revolution before being forcefully supplanted by Lenin and the Bolsheviks. Both men had been members of Russia’s State Duma; one a wealthy industrialist with a moderate, liberal mindset and the other a revolutionary socialist unable to maintain his premiership in the face of mounting pressure to end the war with Germany. Whilst Kerensky was narrowly able to stave-off a coup d’etat by his frustrated military commander, General Kornilov, he was no match for the Marxist hardliner Lenin, whose promise to end the war with Germany would win him the armed support of the people. Kerensky fled first to Scotland, then to London and by January 9th 1920 was alleged to have been telling Central News in America that the British should ‘abandon Kolchak and Deniken and raise the blockade’ (Birmingham Daily Gazette 10 January 1920, page 1). It was his view that the ongoing meddling and sanctions meted out by the West was antagonising the Russian people; Allied Intervention wasn’t defeating Bolshevism, it was strengthening it. The British War Office had one agenda, the British Foreign Office had another (Interview with Kerensky, The Guardian, 30 Jan 1920, p.9).

The reactions of Guchkov and Kerensky to Western intervention in the Russian Civil War after the Armistice of November 1918 couldn’t have been more different; Guchkov was all for it and Kerensky and his former Ambassador Dr. Govransky were vehemently against it. In an address to the House of Commons on June 30th 1919 Dr. Govransky described how Kolchak had ‘usurped’ the authority of Nikolai Avksentiev and the All-Russian Government who had united against the Bolsheviks.

Kerensky had his doubts about the British, but the British had even graver doubts about Kerensky. A letter from Rafael Farina to Commander Ernest Boyce dated just two weeks after his cousin’s murder on the London to Hastings ‘Express’ was querying a possible hook-up between Kerensky and Ignatieff in St Leonards. In a letter addressed to Kerensky in Paris written on January 25 1920, the Paris-based Vladimir Zenzinov writes, “I have not yet thought out how to approach Ignatieff re: the necessary telegram to you (?)” (KV 2/659).

According to an entry in Kerensky’s Mi5 case file dated November 1919, the opinion of Farina had already been expressed in no uncertain terms: “Has been recently in Berlin and is now reported to be in league with the Germans to the detriment of allied interests and to influence Russian public opinion against Admiral Kolchak’s government.” Within hours, a letter was dispatched to the Postmaster General from the British Home Office demanding the interception and inspection of ‘all postal packets and telegrams’ addressed to Kerensky in London and Tunbridge Wells (Alexander Feodorovitch Kerenski, KV 2/658). Whilst many of their suspicions were likely to be unfounded, at least in part, hardcore anti-Socialists like Walter Long, George Makgill and Wilfrid Ashley were given all the excuse they needed pursue a hardline Tory agenda.

Whilst the International Press speculated about his whereabouts, Kerensky kept a low profile in England, quietly negotiating the release of his wife Olga and their two boys Oleg and Gleb. Unlike Kerensky, Olga and the children had failed to escape when the Bolsheviks took control of Moscow. Now they were being retained as leverage in negotiations with the West; guests of Lenin and the Cheka at the notorious Katorga labour camp. The head of Lenin’s new Secret Police, Felix Dzerzhinsky was unambiguous about the matter: ‘As long as they are in our grasp, ’ he wrote, ‘Kerensky cannot do much harm abroad’.

Sometime between September and October 1920 Mi5 intercepted a cipher table sent by the Soviet’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Georgy Chicherin to the exiled Kerensky in London. The table would be used in decoding encrypted messages between the Soviet’ trade delegations in Europe and the Near East. It was a critical time politically and economically for all parties concerned, but publicly, at least, Kerensky and Chicherin sat on opposite sides of the fence. Despite being former allies, the Prime Minister had been Lenin’s fiercest critic outside the White Russians. However, a former member of the Tsar’s Secret Police, still in deep-cover in Moscow, was reporting that Kerensky was frequently alluded to at the Kremlin, and it was his belief that he was “now taking an active role in helping the Bolsheviks carry out their sinister designs” (KV 2/659, National Archives). In all fairness though, it seems entirely more likely that Kerensky was acting as mediator in Chicherin’s trade negotiations with the West, and that his family and the British and French prisoners had become central to unlocking a successful outcome for all sides.

It was October 1920 before the family were released, arriving in Newcastle on false passports, their heads shaved and wearing wigs. News of their dramatic ‘escape’ came within days of Britain publishing a draft Trade Agreement with Lenin’s Soviet (Trade With Red Russia, The Times, October 5th, 1920). The release of 62 British prisoners followed, but with little or no fanfare in the press.

The home where Kerensky was in-hiding — Rust Hall — had been co-financed and extended as a V.A.D Hospital during the war by Rachel Beer (née Sassoon), daughter-in-law of German-born banker, Julius Beer. Rachel’s nephew, Captain Sassoon Joseph Sassoon (1885-1922) had now found himself working alongside Nurse Shore’s cousin Raffaele Farina at Mi5’s G Branch (National Archives, KV 1/52). As a recruitment choice it was either reckless or inspired; Sassoon’s maternal grandfather was Russian Philanthropist, Baron Horace Günzburg, former-treasurer to the Tsar and supporter of Kerensky’s Socialist Revolutionary Party.

Routinely described by the Press as the ‘Rothschild of Russia’, Günzburg had been in a circle of key British allies for years. In 1906, Günzburg in partnership with Arthur Balfour Haig, Basil de Timiriazeff (Russia’s Minister of Commerce) and Frederick William Baker — Chairman of the Venture Corporation — had founded Russian Mining Corporation Ltd at 3 Princes Street in Mayfair. Its objective? To acquire and turn to account “mines and mining properties, rights, concessions and privileges within the Russian Empire.” (Westminster Gazette 01 December 1906 p.19).

Sassoon’s proximity to the Kerensky Government became even greater still when his uncle, the Baron Alexander Günzburg (brother of his mother, Louise), was made President of the Commission that had been duly dispatched to Europe and America by Kerensky in July and August 1917. By contrast, another member of the family, Sir Philip Sassoon had, by February 1920 become Private Secretary to the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George — still regarded as little more than a traitor by Europe and America’s diaspora of White Russians and their madding Tory conspirators. More bizarrely still, one of the friends that Nurse Shore was intending to visit in St Leonards on the day she was murdered was Miss Clara Kelbe, sister of George Gustave Kelbe, a senior figure at the Imperial Bank of Persia on whose board Sir Phillip Sassoon sat. In fact, it was the grandfather of Philip and Sassoon Joseph — the Persian Banking Grandee, David Sassoon — who had provided much of the collateral to set-up the Imperial Bank of Persia in the first place. He had also contributed significant amounts to founding Schröder & Co, where Kelbe’s father had been senior partner (see: The Gang Around George, Communist, 11 November 1920, p.5).

Schröder & Co had already come onto the radar of Section D founder, Sir George Makgill. His own view was that Schröder bank barons John Henry William von Schröder and Bruno von Schröder had been part of an elaborate German plot to undermine Britain’s military capabilities since the early 1900s. In his 1916 article for the British Empire Union, Britain in the Web of the Pro-German Spider, Makgill’s grievances are loud and clear: “Was ever a great empire so humiliated by its rulers? A Hungarian loan was floated by Baron von Schroder, who at the same time assured the Kaiser of his abiding devotion, and who a few months later, after war broke out, was naturalised by our British Cabinet.”

Did Kerensky’s stay at Rust Hall have the backing and support of senior government and industry figures? Was Lloyd George and the Foreign Office involved in complex multi-national deals flying quietly beneath the radar of Mi5?

We might never know. Captain Sassoon’s Mi5 service was cut tragically short, when at the age of just 36, Sassoon died at his home in Paddington. The date was February 7th 1922. It came just one day after Russia’s new intelligence agency, the GPU was formed.

Meanwhile, the numbers making up the Tonbridge Circle just kept on swelling.

Oil Matters

Shortly after the death of Captain Sassoon in February 1922, Russian agrarian economist and alleged rightist, Aleksandr Chayanov, was found to be communicating to Berlin from a nearby Tonbridge address (Letters, 13.VIII.22). Chayanov had arrived in England with Alexander Mikhailovitch Ignatieff, Chief of the Trade Department, to negotiate the terms of the so-called ‘Urquhart Concession’ — a lucrative Anglo-Soviet deal that would help re-establish the vital mining concessions promised to Britain (and America) by the short-lived Kolchak government in Omsk. Among those securing those substantial lost returns was our old friend Sir Walter Long who had invested £500,000 of debenture stock in Anglo-Russian Trust Ltd. In January 1920, as discussion turned to establishing trade with the Soviet, Long had increased that stock by an additional £3,000 (Malone, August 10 1920, House of Commons Hansard).

The irony in all this ran deep; it was Sir Walter Long, as First Lord of the Admiralty, who had imposed the very blockades on Russian ports that Kerensky was demanding to be raised. The squeeze he was placing on Russia was linked — and none too discreetly — to Long’s own private fortune.

And here was another thing. A little earlier in May 1918, Long had set up and chaired the Inter-Allied Petroleum Executive with the US, Britain, France, and Italy enrolling as members. Sir Henri Deterding of Royal Dutch Shell ran the whole thing, but it was difficult not to notice that it was a Signor Farina who assisted Professor Bernardo Attolico and Signor Galli at the Italian Mission in London. Was this Signor Raffaele Farina? The former mining and minerals specialist — and cousin of Nurse Shore — recently recruited to Mi5? The director of Mi6, Mansfield Cumming had written in his diary as early as December 14 1914 that Russia would be the most important country to Britain in the post-war future and that to influence plans and develop trading opportunities they “should sow seed & strike roots now” (The Secret History of MI6 , Keith Jeffrey, p.101). The man Cumming placed as the head of Mi6 in St Petersburg was Samuel Hoare, Conservative MP and long time associate of Sir Walter — Long and Hoare’s father having both served on the board of the Equitable Life Assurance Society. Strangely, the Society’s American counterpart, the Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States, had just won significant concessions to conduct business in Imperial Russia. As a result, Cumming’s man in New York, Sidney Reilly (Ace of Spies) hunkered down at the company HQ at 120 Broadway, knitting together the various threads that tied the Russio-Asiatic Bank to the recently restructured munitions wing of the Russian Supply Committee, both of which shared the premises.

Long’s Oil Executive was concluded in November 1918. It had been a resounding success. As its closing dinner Lord Curzon made his memorable boast: the ‘allies’ he told the diners, ‘had floated to victory on a wave of oil’.

Chayanov on the otherhand probably wished he’d stayed in Tonbridge, as the future wouldn’t prove as kind. Despite his contribution to the Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement he was arrested in 1930; part of an imaginary plot to overthrow the Soviet Government. Seven years later he was arrested again. 24 hours after that he’d been tried and shot.

The race to recover millions in oil revenues lost as a result of the Bolshevik takeover in October 1917 was revived in 1926 when news of an alleged Anglo-German plot broke in the press. The man at the centre of the scandal was none other than Oliver Locker-Lampson, the friend of Sergei Belosselsky Belozersky who lived on the same quiet residential street in Tonbridge as Nurse Nightingale Shore’s aunt, the Baroness Farina. It was yet another attempt to free Russia.

The ‘program of liberation’ this time around was said to have been devised by former German military strategist, Max Hoffmann and ‘Oil Baron’, Sir Henry Deterding of Royal Dutch Shell. Hoffmann, who had spent five years in Russia prior to the war, was certainly no friend of Kerensky, who had personally ordered the last Russian offensive against Germany in July 1917. The ‘Kerensky Offensive’ as it became known, proved to be counter-productive. Hoffman launched a successful counter-attack. The collapse of Russian resistance weakened Kerensky’s leadership and the Bolsheviks emerged as victors. Within weeks, Hoffman had cultivated ties with White Russian forces and cooperated on a Royalist restoration in Russia.