In the aftermath of a fractious year that had seen the much feared General Strike promise to set Britain ablaze with devastating flames of crisis and sedition, the national papers made the most of an unremarkable start to the New Year. The famous Winnats Pass in the craggy High Peaks of Derbyshire, a favourite rambling and cycling spot among Sheffield and Manchester city folk, had been the scene of a ‘sensational discovery’. The bodies of a young man and woman, who had been missing from their homes in Manchester since January 1st 1927, were found at dusk on Saturday 8th by 17-year old rambler Fred Bannister from Manchester. The victims of the tragedy were Harry Fallows of 28 Hinde Street in Moston, Manchester and 17 year-old Marjorie Coe Stewart of 44 Hinde Street.

Incredibly, the story emerged just days before another missing persons’ story had been resolved. Glasgow-born activist Nancy Graham had disappeared from her home on the evening of Wednesday 5th. Her husband, a naval architect trained at John Brown & Co Ltd in Clydebank, had discovered his barely conscious wife a week later in the empty home of a Presbyterian minister in Upton near Liverpool. If the discovery of the bodies in Castleton hadn’t been linked to the Toplis ‘Grey Motor’ case, the story may well have missed the press columns entirely.

The dead man was 26 year-old Harry Fallows, the former corporal in the RASC Vehicle Office at Bulford Military Base who just several years before had been charged with harbouring and maintaining the fugitive Percy Toplis — legendary leader of the mutiny at the Etaples Base Camp in France during the war 1. Archive records show that over a three day period in September 1917, thousands of British soldiers transiting through France had downed arms and rioted over demeaning camp conditions and the atrocious routine abuses being meted out by instructors and camp police. It was rumoured that Percy Toplis was among the more lawless of the men involved. Toplis’ story was eventually re-imagined in the 4-part BBC drama, The Monocled Mutineer in the 1980s, a blistering critique of the war written by Alan Bleasdale, starring Paul McGann and directed by lifelong Socialist, Jim O’ Brien. And for a four-week period in September 1986 it caused nothing short of chaos for the Tory Government.

The facts relating to the ‘Etaples Mutiny’ had been covered-up for the best part of seventy years, partly as a result of embarrassment and partly to suppress a broad scale civil uprising in the immediate aftermath of the war. The fury of the troops had been settled by negotiation. Acknowledging the mutiny had meant conceding the possibility that violent revolution could be a successful model for change. With the exception of the occasional allusion in parliament — usually made by nervous Rear Admirals in hushed, evasive tones or by boisterous Scottish Socialists teasing the cat out of the bag — the mutiny was dutifully buried beneath the thickest of murmurs and whispers. It was only the determination of Douglas Gill and Gloden Dallas — two military historians of a uniquely militant and enquiring bent — that led to it being unearthed and re-examined under a harsh, if not exactly panoptic, academic light (Mutiny at Etaples Base in 1917, Past & Present, OUP, Nov 1975, No. 69). A book by John Fairley and William Allison followed — and the rest, as they say, is unwanted history.

Little is known about the riots themselves. The first national press report on the incident was published some thirteen years later by the Manchester Guardian, based on the eyewitness statement of a junior officer, but anything other than informal oral testimony evidence remains frustratingly thin on the ground and what there is remains dogged by rumour and speculation. As Mark Lancaster, the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Defence confessed in April 2017, the official records pertaining to the Haig Board of Inquiry into the Etaples Mutiny had been lost (Hansard, Citation: HC Deb, 24 April 2017, cW). But there are clues in Haig’s diary and letters written by other officers.

On the third day of the riots Field Marshall Douglas Haig had written in his diary that the disturbances had occurred when “some men of new drafts with revolutionary ideas” had produced red flags and refused to obey orders (Douglas Haig: Diaries and Letters 1914-1918). The Camp Diary of Base Commandant Brigadier Thomson fleshes the story out in a little more detail, whilst leaving out the militant Socialism that may or may not have inspired it.

Some two and a half years after the mutiny, Winnats Pass suicide victim, Harry Fallows had been the star witness at a hastily convened inquest that saw Toplis — the ‘man with a gold-rimmed monocle’ and much-touted ringleader of the mutiny — tried and found guilty in absentia for murder of taxi-driver Sidney Spicer. The theory that Superintendent James Cox of Hampshire Police was pursuing was that Toplis had stolen the car, murdered the cab driver and taken Fallows on a joyride to Swansea, where Toplis then ditched the car after failing to sell it on. A dramatic nationwide manhunt had then been launched before Toplis, the military “Ishmael”, was gunned down by Police in Penrith.

As a result of the 1978 book by John Fairley and William Allison and the explosive drama by Bleasdale in the 1980s, a legend has evolved that the ambush on Toplis had been sanctioned by the British Home Office and secretly coordinated by British Secret Service. It was and remains a far-fetched claim but the circumstances surrounding the death of his accomplice, Harry Fallows in some remote recess of the Dark Peak in January 1927 — so soon after the Great Strike — adds a dash of plausibility. This was a pivotal year for Anglo-Russian relations and Mi5 and Special Branch were up to their necks in intrigue. The notorious Police raid on the Soviet ‘Arcos’ offices in London which took place in May that year, was based partly on evidence that there was Soviet Military spy-ring operating from Longsight in Manchester under the coordination of Cheka agent, Jacob Kirchenstein and featuring Metro-Vickers worker, Fred E. Walker. Just weeks after the death of Fallows, James Cullen — a founding member of the British Communist Party who had been sentenced to one year’s imprisonment for his role in the Etaples Mutiny — published his own account of the riots in France and like Haig he heaped no shortage of blame on Bolshevik trouble-makers. More curiously still, it was on the actual day of the raid of the Soviet offices that Newcastle MP, Sir Charles Philips Trevelyan presented the Access to Mountains Bill to Parliament. A meeting to support the Bill would take place in Winnats Pass that June and it was here that Sheffield and Manchester Socialists declared their full intention to support it. The arrival of former Communist MP, Walton Newbold to contest the High Peaks at the next election, had seen this little-known limestone gorge transformed into a political magma chamber and the death of Fallows, peculiarly enough, had taken place in one of its main vents.

But what does all this have to do with Toplis?

Well one story published in the wake of the villain’s death cast Toplis as an armed and dangerous anarchist with links to an organized Soviet cell operating in the East End of London (World Pictorial News, June 11 1920). Although it’s likely to be lacquered in misconceptions and half-truths, some reports in the Scottish Press at the time of the murder inquiry do much to support the rumour. Arriving at a Temperance Hotel in Inverness, Toplis is reported to have blithely told the property owner that he had “recently been in Russia”. The hotelkeeper went on to describe how Toplis, a ‘modern day Yorrick’, had made quite an impression on guests by delighting them with tunes on the piano in the hotel lounge. The tunes he was most fond of playing? “Nearer my God to Thee and the Russian National Anthem” (Highland News, June 5th 1920). The boasts and his playing of the anthem probably did little to help his cause. There had already been speculation that Toplis had been involved in the brutal murder of former Etaples matron, Nurse Florence Nightingale Shore, bludgeoned to death on a train travelling between London and Bexhill-on-Sea. The Nurse’s cousin, I would learn much later, was the cousin of Raphale Farina, the sitting Head of Mi5’s Russian Section, who was at this time compiling a list of suspected Communist sympathizers and suspicious Russian émigrés active in Bexhill and Hastings.

The role of Harry Fallows in the ‘Grey Motor Car Murder’ inquiry was even less straightforward than the role alleged to have been played Toplis, whose guilt was never firmly established. Despite Harry being arrested as an accomplice in the murder of Spicer, all subsequent charges were withdrawn against him and he was only ever called as a witness at a hastily convened inquest in Salisbury that Toplis found guilty of murder ‘in absentia’. Harry had made no attempt to deny that he had ridden with Toplis in the stolen vehicle immediately after the murder but claimed to have been elsewhere when Spicer was killed. As Toplis was not present at his own trial, and wasn’t in a position to defend his murder conviction, we will never have any way of knowing whether Harry played a hand in the killing, or had acted simply as an accessory after the event. Wrongdoer or witness? It’s likely we’ll never know.

And it’s the lack of credible witnesses and corroborating evidence that makes the whole thing so uncertain. There were no actual witnesses in the ‘Grey Motor’ case. The last fare seen with Sidney Spicer was described as a man of about six-feet in height and over 34 years of age. Press reports citing Toplis’ service records suggest he was 24 years of age and little more than 5 feet 5 inches. The Public Inquest into the death of Spicer was, by today’s standards, a gross violation of justice. The coroner who presided was J.T.P Clarke, Deputy-Coroner for North-West Hampshire, not a civilian but a Captain in the regiment in which both Toplis and Fallows were serving. No one was brought forward to corroborate Harry’s story about being at back at the base when the murder of Spicer took place and no one else came forward to place Toplis at the scene of the crime. Insufficient evidence, no key witnesses, insufficient motives, a mass of contradictory statements, no confession and no forensics.

The entire case against Toplis had built around statements made by Corporal Harry Fallows, who by his own admission had not been present when the murder took place. By the time of the police raid on the Soviet trade offices in May 1927, the only man who could have ever re-examined the death of Spicer, Superintendent James L. Cox, was dead too. The lead investigator in the Toplis case had died suddenly at home in Hampshire, just days before the dramatic raid on the Arcos offices in London, and just months after his old star witness had ended his life in the cave.

There was only one way of moving forward; we would need to go back to the cave.

Fred Discovers the Bodies

At the time of the couple’s deaths in the Dark Peak, Harry was estranged from his wife Alice and his daughter Irene, aged four. His new sweetheart Marjorie Stewart was a fabric designer at Mayne Fabric Company in Salford. She was young, she was happy and a string of creative talents suggested a life full of exciting options. After a brief spell working as a driver, Harry — described by neighbours as ‘a man with a jaunty air’ — had found himself unemployed.

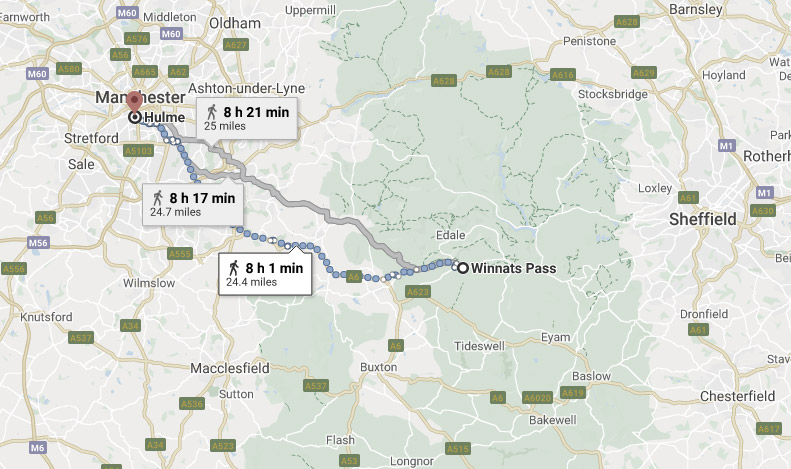

Fred Bannister, the young rambler who had found them in the cave, lived at 21 Upper Duke Street in Hulme in South Manchester. The streets where he lived were made up of soot-peppered red-brick terraces; wall upon wall, roof upon roof, row upon row, each one drowning beneath a dark and pitiful glaze of persistent northern drizzle. The real punch would come on workdays when the rain would mingle with the malted vapours of the nearby breweries and the sulphur of pluming coal fires would cough from the chimneys along the street. According to one member of the press, this small South Manchester suburb was the very heart of an ‘arid region of mean streets and meaner dwellings’. Just 500 yards down the road a pub called Bleak House — a name clearly bestowed on the place by a publican who knew his Dickens — had been resurrected as hostel by Christian ‘stretcher-bearers’ Toc H. The contrast between this and the mortarless moors of the Peaks couldn’t have been more profound. Remarkably, Fred had been living little more than a few miles from the couple he alleges to have found by chance in a cave in Castleton. His father Robert Bannister ran a two property business as a dairyman after spending several years in Australia with his wife Mary Ann and Fred’s half brother Arthur. He’d had a few scrapes with the law for selling watered down milk — both in Oz and in Britain — but was otherwise unknown to Police.

The 27-mile hike from Hulme in Manchester would have been no small achievement for an inexperienced youngster embarking on the journey alone, the recent Winter Solstice having squeezed the hours of daylight into a tight and fairly challenging seven-hour window of opportunity. The shortest route would have taken Fred through the inner city suburbs to Marple Bridge and out onto the Kinder plateau. From here he would trudge his way east through the heather-knitted moors of Edale, mostly likely kitted out in a statutory mix of hob-nail boots, socks pulled up to his knees and the heaviest jacket he could lay his young hands on. It would have been tough going underfoot and after working anywhere between ten and fourteen hour shifts as a labourer, the craving to get out into the hills must have been strong. The 26 shilling wages he would be drawing every week practically ensured a modest kit, and any dawdling or unnecessary sightseeing would have seen Fred tackling the moors in the dark, and almost certainly at this time of year, in the mist. As a reporter for the Sheffield Independent was to write on the Monday, attempting a tramp across the bleak Kinder Scout in the first few weeks of the New Year was a stunt undertaken by “only the keenest ramblers.”

With a good dose of stamina and incentive, it was just about doable — at a push.

Until recently, the road through Winnats Pass was little more than a gritty dirt track punctuated unevenly by heathery tufts and sphaggy moss. A stream coursed through the Pass during the rainy season and on either side of the cleft, steep banks would rise-up to almost impossible angles, flecked with tremendous rocks. Here the tall crags would throw grim, illusive shapes and the rounded, grassy shoulders of the slopes would give way to unexpected, sudden-death ledges. The one hope in the Hope Valley was that you survived long enough to enjoy it. Two parts really creepy to one part ‘holy shit!’

In a report dated Monday 10 January 1927, the morning after his discovery, Fred Bannister tells the Sheffield Daily Telegraph a fairly remarkable story. He had arrived in Castleton on Saturday January 8th to spend the weekend with friends in the village. Around tea-time, curiosity got the better of him and he headed off to explore the caves on the slopes of The Pass. This tortuous, ancient bridle way winds west out of the village and is surrounded by towering ridges, rough pinnacles and silhouettes — a regular magnet for adventurous youths. At approximately 5.00 pm Fred entered a cave to the right of the foot of The Pass, and it was here that he found the bodies of the couple in the entrance to the cave. His story was made all the more remarkable because he had encountered the very same couple — only this time very much alive — in the same spot just seven days earlier (Sunday January 2nd).

His journey on that first week had been little different. Two rambling friends from Manchester who Fred knew only as ‘Sunshine’ and ‘Ambrose’ had set off with him on the Sunday and they had arrived at the Winnats Pass around 4.30 in the afternoon. Fred described how the couple at the time of this first sighting had been ‘sitting side by side in the dark’ at the cave entrance (Sheffield Daily Telegraph 10 January 1927, p.5). “We had torches and they told us to put them out. It was the man (Fallows) who asked us, and he spoke in an ordinary way, without any sign of agitation or anything to arouse our suspicion.” In the aftermath of the drama Fred had talked to other ramblers who had gone into the cave a little earlier in the day and they told him they had found nothing unusual inside them. If Fred’s story is correct, then Fallows and his sweetheart must have arrived at the caves shortly before Bannister and his group, and slightly later than the other ramblers.

(Sheffield Daily Telegraph 10 January 1927 )

When the reporter pressed Fred on why he had headed to Castleton on the Saturday he discovered the bodies — the weekend after his trip with ‘Sunshine’ and Ambrose — the boy said that he had arrived to stay the weekend with Mr and Mrs Younge of The Island Gift Shop, situated just off Buxton Road. Tea-room and gift shop owner Henry Younge and his wife Hannah were the parents of Harry George Younge, a keen fell runner who had married 27 year old Clara Bellass some three years earlier. Clara, a supervisor at Metro-Vickers at Trafford Park were now living at Trafford Grove in Stretford, putting them little more than a few miles from young Fred in the southern districts of Manchester and just a hundred yards from future Communist and A.E.U leader, Hugh Scanlon on Chester Road. It also placed Clara tantalisingly close to suspected Soviet agent, Fred E. Walker, another Metro-Vickers employee.

In previous years the Younge’s son, Harry Jnr. would lead celebrations as the garlanded King’s Consort on horseback for Castleton’s legendary ‘Oak Apple Day’ — a relic of the old Stuart dynasty commemorating the restoration of the monarchy in the 1600s. By 1927, the whole event had been largely forgotten. It was only in quirky backwater strongholds like Castleton that this rather Conservative celebration still thrived.

Another key figure at the Oak Apple Day celebrations was 44 year old Arthur Potter, a guide to the local Speedwell Cavern. The cavern stands to this day some 75 yards from the cave at the entrance to The Pass. Just a few years later, Potter’s hostility towards the mixed-sex rambler camps dotted around Winnats Pass would culminate in a campaign to stamp the nuisance out once and for all. As he and other ‘Castleton Ringers’ saw it, the rambler’s camps were a ‘disgrace to civilization’. The “free and easy manner” in which the sexes were mixing was totally unacceptable and something needed to be done (Sheffield Independent, 07 June 1935, p.7). Castleton’s Tory MP, Major Samuel Hill-Wood probably couldn’t have agreed more. In the Major’s eyes, most of the ramblers were unruly young Socialists and ‘the bulk of the Labour Party were Bolsheviks’. Hill-Wood’s fight was not with the honest and decent men who represented the unions but with ‘them’ — the extremists (Derbyshire Courier 11 September 1920, p.3) Going toe-to-toe with daring former-Communist, J.T. Walton Newbold in the High Peaks local elections of June 1927 would only sour his opinion further. But this is something we’ll need to come back to.

Before making his way to Mr and Mrs Younge at the Island, Fred says he had gone alone to explore the caves at Winnats Pass. The time would be around 5.00 pm. He says he passed the cave, which though some 800 yards from the village is just about observable from the narrow mud-track road that zigzags through The Pass. The ‘Horseshoe Cave’ as it was then known, lies some 100 yards up a gentle incline.

Gales were blowing in from the East the day Fred returned to the cave that Saturday. Almost a full week had passed since his first trip to the cave and a deep depression was now sitting between Scotland and Iceland. As a result there had been widespread flood damage across Britain. The moors around the Peaks had also seen considerable snowfall. The first few days of the New Year had been relatively mild and Fallows and Stewart are likely to have encountered little more than drizzle if they had arrived in the Peaks on New Year’s Day. The temperatures though were dropping and it’s unlikely the couple could have survived a full week in the caves without any kind of provisions. When Fred Bannister arrived at the caves, the pass was being battered by a ‘terrific rainstorm’ (Dundee Evening Telegraph 10 January 1927, p.3).

Although Fred says he had passed the cave at first, something had told him to go back. He returned and entered the outer cave, before squeezing through a bottleneck passage about fifty yards inside. It was here that Fred flashed his lamp and made out the legs of a woman, reclining against a rock. She wasn’t moving. Fred’s first instinct was to exit the cave, but composing himself he returned and felt the woman’s pulse. She was cold. He felt nothing. Horrified he ran out, having seen nothing of the man. “As I passed Speedwell Mine, I blew a whistle I carry, but there was no one about, and I ran down into the village of Castleton and informed Police Sergeant Barrett”. Sergeant Barrett and Dr Bailey accompanied Fred back to the cave, and it was then that the body of Fallows was found, lying face down some 10 or 15 yards away from the girl. Both were fully dressed and a broken cup and saucer was between them. A full bottle of Lysol disinfectant was in Harry’s coat pocket and a second broken bottle was found lying at his side. At the feet of the woman reclining against the rock was a handbag. Nothing in the way of provisions or extra clothing were found. A cursory examination of the handbag revealed only a manicure set, a powder puff and a ticket with an address and a telephone number on it. The number and address was that of a woman who Marjorie had exchanged Christmas cards with just weeks before. Dialling the number, Superintendent J.H MacDonald learned that Marjorie had been missing for a week. The man had been absent from Manchester for some days.

In spite of Fred’s story about seeing them alive at the cave the week previously, there was no evidence to suggest that the young couple had been staying in the village from the time of their disappearance on January 1st to the discovery of their bodies on January 8th. No witnesses came forward to say that they had been seen and no one came forward to say whether the missing couple were even familiar with the Castleton district. Fred’s two young rambling friends, ‘Sunshine’ and ‘Ambrose’ may have been able to shed some light on the claims, but curiously the pair never came forward.

After the Police Sergeant and the Doctor had completed their review of the cave, Edward Medwell, a greengrocer and village sexton, who had married the Younge’s daughter Doris, conveyed the bodies from the caves to the Castle Hotel in his van, battling against the pummelling high winds which had prevented the van from turning and driving back for quite some time. Once the van did manage to get away, the helpers at the rear of the wagon were seen to topple awkwardly over the bodies. The gale coursing through The Pass provided nothing in the way of shelter and even less in the way of mercy.

The Sheffield Telegraph wasted no time in pointing out that whilst Winnats Pass was frequently visited during the summer months, particularly by Manchester people, winter visitors were comparatively rare. Neither the doctor nor the constable was able to say if Fallows had taken his own life before or after Marjorie, although the pair of them were both believed to have been dead some days. There were no signs of a struggle and their bodies were ‘well clothed’ in their everyday city attire. As Dr Baillie explained to the press, “they were obviously not ramblers” (A Dead Couple in A Cave, Dundee Evening Telegraph 10 January 1927, p.3). If what Dr Baillie says is true, then they were also not sufficiently kitted out for spending five days in a cave in the High Peaks in winter. So where did they stay and what had been the couple’s movements since they were last seen on Friday 31st December?

At 2.30 pm on Sunday 9th January, Mrs Lily White, the sister of Harry Fallows, arrived in the village with her father, Edwin. They spent a few minutes at the Castle Hotel identifying the bodies and after a brief conversation with Sergeant Barnett returned to Manchester. The hotel occupied a fairly private location just off Cross Street, a hundred or so yards from Bannister’s friends, the Youngs at The Island Gift Shop. The once mighty Peveril Castle loomed high on the cliffs above it, offering a safe, reassuring embrace. Marjorie’s sister and parents, William and Hannah visited the home of the minister where they discussed the business of burying the couple together — an unconventional enough arrangement even under normal circumstances, and certainly more so now given Harry was still married to Alice.

Mass Ramble in the Pass

If Fred Bannister’s account was accurate, then Harry and Marjorie would have arrived in Winnats Pass when it was crawling with hundreds of ramblers. This was a key date on the walking calendar: a New Year’s rambling celebration at the Peak Hotel in Castleton wedged neatly between a series of mass tramps across the moorlands of Kinder Scout — the highest point in the Peaks. Despite protests, the pathway across the mountain had been closed in recent years and an annual ‘mass trespass’ had been built into the fabric of the celebration. As local rambling organiser, G.H.B.Ward was in the habit of repeating, rambling “did not consist of a perambulation from one public-house to another” or “disrupting Sunday morning worship” with the pumping of some heinous concertina on street corners. An open and honest roam across Kinder was all they sought, and a vow had been made to go there every year until they could cross it as ‘free men’. It may have been a whole New Year for the Clarion Socialist men and women, but it was the same old battle they were fighting.

Turn-out had increased three-fold and many of the group had started out the previous morning, some getting the train from Manchester, whilst members of the Sheffield faithful had started off on foot from Fulwood by way of Stanage Pole. All being well, there would be a welcome meeting at the hotel on the Saturday before walks would conclude on the Sunday with a tramp across Kinder.

It was ramblers’ day and ramblers were everywhere.

Reporting the event on Monday January 3rd, The Sheffield Independent wrote,

“At every bend in the winding moorland path, and at each guide-post that marks the twisting lanes the wanderer would have been met with cheery greetings for the New Year. Some were veterans of the game, others were young and vigorous, and quite a number were girls, bobbed and shingled, who strode alongside their male companions quite unabashed in heavy boots and breeches. The majority of youths were hatless and bare-necked, although one braved hill and dale in Oxford bags and a beret.”

Sheffield Independent 03 January 1927, p.10

The hundred or so ramblers were drawn from all parts of the surrounding districts: Rotherham, Worksop, Sheffield, Manchester, Rotherham and Barnsley. As on most other occasions turn-out was very good and this year the annual New Year tramp would be celebrating its 26th anniversary. Among those likely to have attended the Mass Trespass on Kinder Scout on the Saturday would be future Trespass leader, Benny Rothman and his young friend, Hugh Scanlon, the future Communist and A.E.U leader who lived just 100 yards from Clara Bellass and Harry Younge at 8 Trafford Grove in Stretford.

As usual, the man who had organised the event was G.H.B Ward, founder of the Sheffield Clarion Ramblers, formidable Labour activist and self-styled Prince of the Ramblers. “The truest rambler could go anywhere”, Ward would say as he prepared the annual toast on the first day of 1927. The resolution this year, as it was every year, was the relentless, blister-popping advance toward self-improvement: mentally, physically and spiritually. In Ward’s eyes the finest nation would be the one where the greatest percentage of its people were disciples of the open air. For Bert it was about the working man or woman seizing control of their destiny, plotting a course and preparing for a life with purpose and direction. As one ascended Kinder Scout the soul would climb and a sharp, north-easterly wind would whip away the dust from the eyes and send a shiver of self belief rattling down the spine. The gravel beneath ones feet gave way equally to knight or knave, sire or scuzzer, baron or bastard. Ward, who had forged a close personal friendship with the Spanish anarchist revolutionary, Francisco Ferrer during his trips to the Canary Islands at the start of the century, said that rambling stood for the ‘pride of a manly heart, a swinging stride and a personality that could penetrate and was not afraid’. When thumping your boots down on the beautifully scarred soils of the Peaks, the working man could enjoy the same natural rights as his landed masters. The revolution, one might surmise, would start in the lungs and the heart and the spirit. He may have forged his trade amongst the smouldering twisted metal of the steelworks of Sheffield, but he had the restless soul of a poet.

The custom was to hold the Clarion Club’s annual New Year dinner on the first Saturday evening of the year at the Peak Hotel. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph of January 4th reported that the club’s members spent a jolly evening singing songs and making merry. Ward made a toast to the Club’s treasurer W.H Whitney, and remarked that the Clarion Socialists were now like an oak tree — well-established, strong with numerous branches. If they wanted the moors to be free, they must free it for themselves. Rambling was the sport of levellers, smoothing away the social boundaries that divided men of small and large means. As celebrations got underway a glass was raised to rambler James Evans, a Manchester railway worker who had gone missing not far from Castleton in the first week of January 1925.

Knickerbocker Bolsheviks

The weekend of the New Year Clarion Ramble was also marked by the arrival of the Young Communist League, a more unmatured blend of the two local radical youth organisations: the Young Workers’ League and the International Communist Schools Movement. The group, led by the indomitable William Rust, embraced the same purposeful stride and free spirit of the Clarion Ramblers and provided a fractious rearguard at the landmark Winnats’ Pass rally arranged by Ward just six months earlier. Rust’s influence was at its peak. As Fallows and Stewart prepared to spend their very last Christmas together, Rust was marching his 120-strong YCL members through the streets of nearby Sheffield to the Primitive Methodist Chapel on Stanley Street, home of the Amalgamated Engineering Union, where Ward had been serving as Chairman 2.

Sources

Ramblers Grim Discovery: Winnats Pass Mystery, Sheffield Independent, January 10th 1927, p.1

Two Bodies Found In Castleton Cave, The Manchester Guardian, 10 Jan 1927 p.9

The Castleton Cave Inquest, The Manchester Guardian, 12 Jan 1927, p.2

Hull Daily Mail 10 January 1927, page 8

Cave Deaths, Daily Mail, Jan. 12, 1927

Festival Day For Ramblers, Big Tramp Over the Moors, Sheffield Independent, January 3 1927

Communism in Britain, 1920 – 39: From the Cradle to the Grave, Thomas Linehan, Thomas P. Linehan (see the chapter Communists at Play for coverage of mass rambling, pages 150-157)

Nonconformity in the Manchester Jewish Community, The Case of Political Radicalism 1889-1939, Rosalyn D Livshin

Aubrey Aaaronson, British Services Records, National Archives, Regimental No. 34146, 3rd Border Regiment

A Manchester Diamond Merchants Adventure in London, Manchester Guardian, 18 May 1912, p.12

The Lower Deck of the Royal Navy 1900-39: The Invergordon Mutiny in Perspective, Anthony Carew

The All Russian Cooperative Society (Arcos), KV2/818, National Archives, Kew

A History of the Peak District Moors, David Hey

Crime and Consensus: Elite Perceptions of crime in Sheffield: 1919•1929, Craig O’Malley, 2002

The Fifth Commandment, Biography of Shapurji Saklatvala, Sehri Saklatvala, Miranda Press, Salford, 1991

Death at Sheffield of Mr William W. Chisholm, Nottingham Journal 09 September 1935, p.11

Across the Derbyshire Moors, John Derry/GHB Ward, Sheffield Independent Press Ltd

Mutiny!, A Killick (Private No. 08907 RAOC), Spark, Brighton 1968

Red Schoolboys Trade Union, Sheffield Independent 21 December 1926, p.7

A Communist at Twelve, Rhondda Boys Russian Visit, Western Mail 20 June 1927, p.9

Sources for the Study of the Kinder Trespass, 1932, Sheffield City Council