On Saturday January 8th 1927 the bodies of Toplis accomplice Harry Fallows and his sweetheart Marjorie Stewart were found dead in a cave in Castleton. Within weeks the leading detective in the Toplis investigation was also dead and the first eye witness account of the Etaples Mutiny would be published in the British Press. Was it suicide or was it murder?

Lysol Poisoning

The formal inquest that took place on Tuesday January 11th ruled that the couple’s death had been caused by Lysol poisoning. This would have been a horrible and prolonged death, although by 1911, ingesting it had become the most common means of suicide. Swallowing Lysol would have caused nausea, vomiting, circulatory failure, respiratory failure, central nervous system depression, liver dysfunction and eventual kidney failure. Given the relative availability of service revolvers still in circulation after the war, this would have been a slow and agonizing way to go. Death would not have been instant and it seems inconceivable that their screams wouldn’t have been heard by the scores of jolly ramblers swarming around on the slopes and in the caves around Winnats Pass. The cave, whilst not visible from the roadside, was still only a matter of yards away from what would have been a busy thoroughfare during the weekend of the annual Clarion Ramble.

Marjorie’s father, William Stewart a driller at Newton Heath Carriage and Wagon Works told the inquest that he had received a telegram from his daughter handed in at a Manchester Post Office on the Friday evening telling him that she had gone away with Harry. The following morning he received a separate message from Fallows, confirming the arrangement. Marjorie’s father had spoken to Fallows a few years previously and expressed his desire to see Harry’s relationship with his daughter terminated. As a result, Harry was forbidden from entering the house. The father was unaware that the relationship had continued, and said the messages he’d received from the couple had dealt him a serious blow. Fallows was unemployed and had separated from his wife just nine months before by mutual agreement. Much of the money he received was sent to his wife in Crumpsall.

It had been a tough twelve months for William. Just eight months earlier he had been among 3,000 workers walking out at the Newton Heath Carriage and Wagon works. The one day strike came just 72 hours before the General Strike was announced on May 2nd, but hadn’t been called with the backing of the union (Newton Heath Carriage Works, Leeds Mercury 29 April 1926). The last time he saw his daughter alive was at 7.00 am on the morning of December 31st — New Year’s Eve — when the girl had left the house for work at the fabric mill.

Despite the messages from the pair, William reaffirmed that there was no indication that the pair were about to take their life. Harry’s telegram had stated fairly prosaically that whilst he regretted the impact their decision to elope would have on the Stewart family, there was nothing at all wrong in their relationship.

As far as William was concerned, his daughter had left that morning, “happy, contented, bright and cheerful” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 12 January 1927, p.6). Her employer at Greengate in Salford said much the same thing; Marjorie was ‘artistic, bright and cheerful’. All who knew her were dumbfounded by her death: she was an ‘expert’ pianist and a talented singer. She was a good designer, liked her work and was well thought of by all who knew her. How she had been taken in by the charms of a bespectacled married layabout like Fallows was anyone’s guess. Speaking to a reporter at the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, the forewoman in charge of the girl’s department described how Marjorie had taken part in the Christmas Festivities and when paid her wages on New Year’s Eve had made no mention of her trip to Castleton.

Harry’s sister Lily White of 28 Hinde Street, Moston was the next to face the coroner. Lily lived just a few yards down from the Stewarts and had last seen her brother at 2.45pm on December 31st. He had been living with her on and off since the previous March, arriving back in Moston some weeks ahead of the General Strike. He had found some occasional work as a cab driver and mechanic, but had been living mostly off unemployment benefit and some regular gambling wins for the duration of his stay. One man came forward to say that Fallows was always boasting about his winnings. “One day he would say he had won £50 and then another day it would be £60 — and all on a tanner double.”

Like William she too received a letter from Harry the following morning saying he was unlikely to be back in Moston for several weeks. He had gone away with a girl he was very fond of. As with the message received by Marjorie’s father William Stewart, there was nothing to intimate they were going to take their own lives. On the contrary. When asked by the Coroner if there was anything to suggest that Harry was tired of his life or wished he was dead, she said that he was “much too happy for that”. He’d gone away on other occasions and always come back.

Fred Bannister, the boy who had found the bodies during the second of two visits to Castleton was the next to face questions. He repeated his claim that he visited the entrance to the cave the previous week, but this time there were two subtle changes in young Fred’s narrative; this time he was alone when he made the first of the visits and he hadn’t seen Marjorie Stewart:

In reply to the coroner, witness said he visited the cave a week previously, but only went into the entrance.

(Sheffield Independent 12 January 1927, p.5)

But did you go far enough into the cave to see if the woman was there then?—She was not there.

This statement Fred made was a complete contradiction of what he had told the Sheffield Daily Telegraph and Sheffield Independent reporters just 48 hours before: “We (Fred, Ambrose and Sunshine) arrived during our walk just outside where the bodies were found. We saw this couple — I am quite certain they were the same two — sitting side by side in the dark at the entrance” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, January 10th 1927, p.5)

In the statement he provides to the reporters shortly after finding the bodies, Fred says that he, together with his two friends ‘Sunshine’ and ‘Ambrose’ observed Marjorie Stewart sitting with Fallows in the entrance to the cave on the first of his visits to Castleton, yet in the account he gives at the inquest, Fred arrives alone and Marjorie is missing.

The Coroner continued the inquest with some questions about the second of the trips Fred made to the caves on Saturday 8th — the day Fred discovered the bodies. Among the items he found were a ladies brown crocodile leather handbag, a pair of leather gloves, a green felt hat, a pair of broken spectacles, a gent’s bowler hat and a cup and saucer marked, ‘A present from Castleton’ — quite possibly purchased from the tea-room and gift shop owned by the couple that Bannister was visiting. The owner of the gift-shop asserted that ‘unknown woman’ had bought the cup and saucer on Saturday the 1st — New Years Day — and the day of the annual Clarion gathering (Sheffield Independent, January 12th 1927, p.5).

Dr John W.W. Baille told the inquest that there was no sign of violence on the girl’s body and he had come to the conclusion that she had died as a result of a corrosive poisoning. The back of the man’s throat had a ‘white, puckered appearance’ and there was a brown stain on his chin from vomiting. The usual tell tale signs of severe burns to the lips and mouth were not recorded. The next part was a little more confusing. When asked how long Harry and Marjorie had been dead, he replied that the couple had probably met their deaths between two to three days before the discovery of their bodies on the evening of Saturday 8th. Rigor Mortis had just begun to pass off the body (about 36 hours). If correct, then Harry and Marjorie had survived the best part of a week in the cave without once being seen by anyone in the village with the exception of young Fred Bannister.

The coroner had a problem. He’d clearly got wind of Fred’s statement to the press and was keen to press him on the subject of Marjorie and whether she was or wasn’t sitting in the mouth of the cave on the Saturday. The two accounts related by Bannister were beginning to provide more questions than they did answers.

The basic gist of what the young lad was now saying was this; Fred walked alone from Manchester to Castleton on Sunday January 2nd. As he explored the caves in Winnats Pass he saw Harry alive in the entrance to one of them — but not Marjorie. A week later on Saturday January 8th he walked again from Manchester to Castleton, retraced his steps to the cave and this time found the bodies. According to the doctor, the bodies had been lying in the state they were in around two or three days, suggesting death took place between the Wednesday 5th and the Thursday 6th January.

What the couple had in the way of food provisions isn’t known. Despite exhaustive door to door enquiries, no one was able to shed any light on the matter. The residents of Castleton had absolutely no knowledge of the pair. The only person who appears to have seen them was Fred Bannister and his friends on the Saturday. No shops or tea-rooms had served them food, no one had sold them blankets, no hotel, inn or guest house had provided them with rooms and yet the couple had stayed the best part of a week just five hundred yards away from the village without arousing any kind of suspicion.

This was a tight-knit place, with a population just short of five hundred. Whilst the weekend of their arrival would have seen Winnats Pass swarming with excursionists from the surrounding towns and cities for the New Year Clarion Ramble, a stranger in a bowler hat and a lady in a green felt hat would certainly have made an impression when the village returned to normal the following week.

How Did The Couple Arrive in The Pass?

If the couple had arrived with the necessary provisions to spend a full week in the cave, then it’s likely they had arrived in Winnats Pass by car. But if they had arrived by car, then where was the car? And if on the off-chance they had been dropped-off in The Pass by a friend, hired a cab or taken a bus, then why had a driver or other passengers not come forward? More bizarrely still, the couple had arrived at the cave little better equipped than for a night on the town. A gentleman’s bowler hat? A lady’s mackintosh? A crocodile skin handbag? They would have been lucky to survive a night in the High Peaks in winter dressed like this. Conditions in the cave were far from comfortable with several eyewitnesses recording that pools of waters dominated the areas around their bodies, formed from the drippings that percolated through the side of the gorge. The chances of catching a few hours sleep would have been slim.

Winter conditions in the High Peaks are notoriously unstable. Night time temperatures at this altitude will rarely exceed 1°C on average, which over the course of several hours or several days, would inevitably lead to mild to severe hypothermia. To have survived five or six nights in the cave as indicated by the coroner would have been close to a miracle. The couple’s resolve to end their lives would have needed to endure an enormous practical challenge. Putting it off and extending the wait under such pitifully shit conditions would have demanded a greater sense of fortitude and patience than Lysol suicides typically possessed. The vast majority of Lysol poisonings being reported at the time were either preceded by a significant trigger event or carried out during intense manic episodes. And why bother waiting at all? Their clothes would be wet, their brains confused, their stomachs empty. If any one of them had been in the least bit unsure about the extreme measures they were about to take, the reflex action would have been to bolt. And if they had, like the Coroner suspected, spent the week in lodgings elsewhere then it was fairly customary among suicides to end their lives in the relative comfort and privacy of their own hotel room. The press columns were full of them.

If you were to follow the logic, there was two real possibilities: the couple had not been seen by Fred outside the cave on Sunday January 2nd but had arrived at a later date, or the post-mortem had it wrong and the couple had died within hours of arriving in the cave sometime between Wednesday January 5th and Thursday January 6th.

More Echoes of the Toplis Case

Despite the unusual circumstances and many unanswered questions, the coroner advised the jury to record a verdict of ‘Death from Lysol Self Administered’. The Press mentioned the story’s relevance to the Toplis investigation, but it was not explored in any significant detail. ‘Dead Man’s Connection With Toplis Case’ wrote the Dundee Telegraph, ‘Toplis Case Recalled’ wrote another. Many of the reports recalled the startling ease with which Fallow had avoided criminal charges. He had been acquitted and discharged, probably on account of his cooperation during the manhunt launched to find him.

The Toplis case was further recalled just a few months later when Superintendent James Lock Cox, the detective who led the hunt for Toplis and brought Fallows in for questioning, died suddenly at his home in Andover. A keen sportsman and active Councillor, the detective was dead at just 49 years old (Daily Mail, May 09, 1927, p.9). If the news story about Fallows had grabbed the attention of the former Superintendent in the last few weeks of his life as he thumbed through the headlines of his morning newspaper, then he sure as hell wasn’t going to be able to pursue it now. Short of springing back to life, the unexpected suicide of his key witness in the most baffling and tragic of circumstances, meant any lingering doubts that ex-Superintendent Cox may have had about the Toplis case, would now be buried with him.

For Charles de Courcy Parry, the Cumberland and Westmorland Police Chief who orchestrated the ambush on Toplis, the future wasn’t quite so grim.

On March 12th it was reported that the new British Home Secretary, Sir William Joynson-Hicks would be bringing Parry out of early retirement and appointing him HM Chief Inspector of Constabulary for South Wales with effect from April 1st. It was an appointment that would mark the beginning of a new and urgent offensive against the domestic Communist threat. As far as the Conservatives were concerned, the Bolshie heartlands of ‘Little Russia’ — the Rhondda Valley — and the colliery districts of Monmouthshire remained of key strategic importance in Soviet efforts to extend the Communist International.

Within five weeks of Parry taking up his new role at the Home Office, Special Branch mounted a raid on All Russian Co-operative Society and Soviet Trade offices in London. The raid was based on intelligence provided by the SiS and Mi5 indicating that the Communists had illegally copied SIGINT documents from a military training base in Aldershot. Joynson-Hicks, the man responsible for bringing Parry out of retirement, was a fierce anti-Communist, and in light of Harry’s death in Winnats Pass, it’s intriguing to note that it was also Joynson-Hicks who conceived of the show trial of ‘mass ramble’ organiser, William Rust of the Young Communist League just 14 months previously.

Ahead of Parry’s reappointment, Home Secretary ‘Jix’ as he was known told members of the Commons that the anti-British activities of Communist agitators were being closely monitored and that he would seeking new statutory powers to deal with the emerging threat (Leeds Mercury, February 25 1927, p.6)

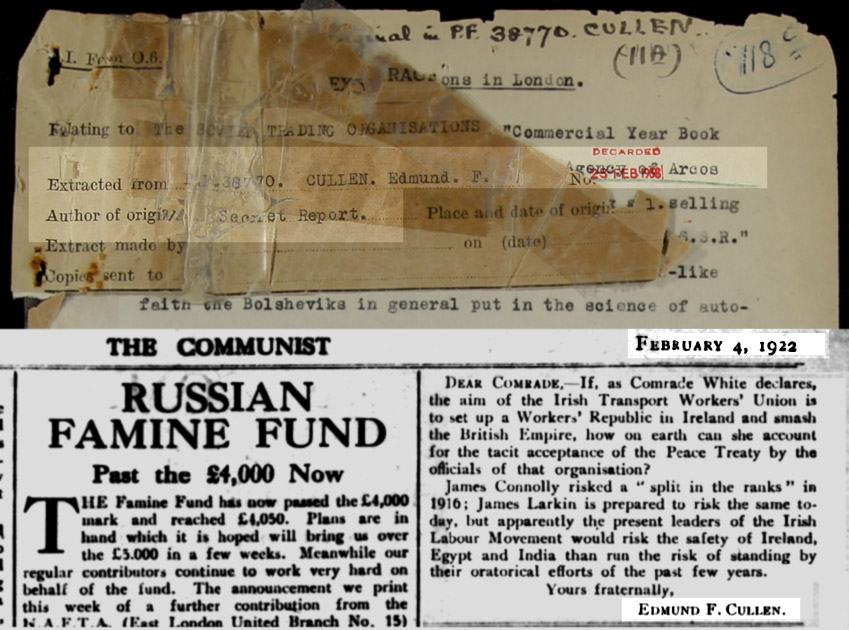

The Home Secretary’s announcement was accompanied by a series of articles in the Glasgow Weekly Herald which saw Etaples Mutineer, James Cullen provide a blistering four-part insiders’ account of Russian interference in the 1926 General Strike: “I am quoting from the Official Press of Russia when I say that that millions upon millions of Russian Workers contributed part of their wages to help promote the General Strike … the Second International is endeavouring to sow dissension among the struggling British workers.” Cullen went on to describe to his readers how throughout the General Strike private negotiations had taken place between the Secretary of the Miners Federation, Arthur J. Cook and senior officials in Moscow. The claim was fortified by an account of his own experiences of Etaples and the Bolshevist agitation that led to the riots:

“My own connection with this movement dates from the year 1917. It was while I was in France with the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders that a seditious leaflet fell into my hands. It was of a most inflammatory nature, and bluntly asked the troops to ground arms and stop this war. At this time the Bolshevists knew the troops in France were in no very nice mood. In fact they were at fever-pitch, and it only wanted a spark to cause a first-rate explosion. That spark came when a corporal in the Military Police stationed at Etaples shot a Gordon Highlander.”

Bolshevism in the Army, Glasgow Weekly Herald, James Cullen, Feb 19 1927

Despite there being no specific reference to “Bolshevists” and “Russian brothers” in the official camp diary kept by the depot’s much maligned Camp Commandant, Brigadier General Thomson, Cullen’s claims echoed the diary entries of Field Marshall Douglas Haig who wrote that “some men of new drafts with revolutionary ideas” were among those who had triggered the violence. A short eyewitness account of the riots published in The Worker’s Dreadnought some six weeks later supported the claims: “About four weeks ago about 10,000 men had a big racket in Etaples, and they cleared the place from one end to the other, and when the General asked what was wrong, they said they wanted the war stopped” (Worker’s Dreadnought, November 3 1917, p.1).

If the question is whether it was a spontaneous groundswell of fury and exasperation among the troops over appalling camp conditions that led to the riots or a coagulation of radical influences taking shape among the Socialists and shell-shocked veterans at the sprawling depot, then the truth probably lies somewhere in between: there was the tinder, and there was the spark.

Tensions at Etaples camp had been running high for months. Copies of The Worker’s Dreadnought and The Weekly Herald — the official organ of the Independent Labour Party — had already been banned from the base. Alfred George Killick, a keen Clarion rambler and cyclist was The Herald’s distribution manager in France. Alf was subsequently charged with sedition during the Calais Mutiny of 1919. John Thomas Pantling, charged alongside Killick, was another lifelong Clarion Socialist. As Killick explained in a pamphlet he published years later, they “weren’t just another lot of disgruntled and dissatisfied men … there was a large element of political consciousness”. To make matters worse, the former, Socialist Revolutionary Victor Grayson — a lifelong friend of the paper’s editor, George Lansbury — had marched into Etaples on the very same day and the very same camp in which the riots would erupt.

The riots also coincided with a campaigned launched by Lansbury to tag the rights of the British Soldier onto the upcoming Representation of the People Act. Lansbury’s objective was to ensure that every man over the age of eighteen serving in the British Army was given the right to vote.

Surely the British Parliament will wake up and before the Reform Bill goes through, add it to a clause securing to every man serving with the colours the full rights of citizenship. Officers already have these rights. They have only to change out of their uniform into private clothes and at once they can take part in politics.

The Herald, November 10 1917, page 3

The Herald had made the same appeal on September 1st, when it was reported that a cease and desist order had been posted up in camps calling attention to Kings Regulations Paragraph 451, forbidding men to institute or take part in any meetings, demonstrations or processions for any party or political purposes, in barracks, quarters, camps, or their vicinity — and certainly not in uniform.

Extraordinarily enough, Lansbury’s appeal for Soldiers’ Rights had also sought the support of the ultra-patriotic National Party, launched by General Henry Page-Croft just one week prior to the mutiny (National Party Manifesto, Statement of Aims, The Times August 30 1917). The purpose-built party’s objective was pretty straightforward: settle existing class, sectional and sectarian issues without recourse to Socialist principles and give the soldier and munitions worker what they needed: fair wages, a kick-ass National Defence and a ‘vigorous diplomacy to support the fighting men in their heroic struggle for victory’.

Page-Croft had campaigned on the issue of Soldiers Votes for years. Just 12 months previously a meeting had taken place at the Queens Hall to demand that soldiers and sailors on active service abroad or at home should be given the right and facility to vote at the 1918 General Election. On that occasion, Page-Croft was joined in his appeal by ‘Unseen Hand’ conspiracy theorist, Leo Maxse, proto-fascist Arnold White and British Suffragette, Emmeline Pankhurst. Pankhurst didn’t mince her words; our fighting men, she said, had proved their entitlement to vote by making it possible to keep a country in which to vote. Not doing so, Leo Maxse went on, was akin to disfranchising the Victoria Cross.

Horatio Bottomley — a close friend and ally of Page-Croft — had arrived ‘by chance’ in the town of Etaples, just days before the riots took place. The newspaper editor and Hackney MP and would end up negotiating a settlement to the demands of the troops and play a vital role in persuading the men to dump their placards and return duty. Upon leaving the army in 1919, Grayson ditched his support for the Revolutionary Socialist movement and moved across to the no less revolutionary National Party who had a more insidious new battle to fight: the illegal sale of honours in David Lloyd George’s government. 2

What, if any part, Grayson played in the mutiny isn’t known but his appetite for direct action was well acknowledged, both in London and in Belfast 3. He was a specialist mob orator. The rhetoric was strong, the metaphors were rich and blood would literally boil as the verbal blows and the bombast flowed. Syncing his arrival at Etaples with a ‘spontaneous’ grassroots rebellion may have been all Lansbury and Page-Croft needed to bulldoze the Rights of the Soldier on to the Representation of the People Act. Faced with an abrupt end to the war with Germany, the British Government would be forced to listen. It was something that every anarchist and every patriot could get behind.

In October 1909 Grayson had addressed 8,000 members of the Social Democratic Federation and Labour Party who had gathered in Trafalgar Square to express their fury at the execution of anarchist Francesco Ferrer. From the base of Nelson’s column Grayson denounced the killing with a rousing and violent speech, advocating ‘a life for a life’ before declaring that even if ‘the heads of every King in Europe were torn from their trunks tomorrow it would not pay half the price of Ferrer’s life’. By whatever means, the death of Ferrer “would be paid in full” (The Execution of Ferrer, The Times, Oct. 18, 1909, p.8). Immediately after his speech, a breakaway procession made its way to the War Office where they were charged down by mounted police. The man who had helped organise the demonstration in London was Ferrer’s close personal friend, G.H.B Ward, the man in charge of the Clarion Rambler’s annual celebration in Castleton.

Grayson and Ward were reunited again in 1912 when their mutual friends and comrades, Guy Bowman and Tom Mann were charged with authoring a pamphlet encouraging British troops to mutiny. According to Mann’s memoirs, there is some indication that Victor Grayson was very nearly arrested too alongside the pair (Tom Mann’s Memoirs, MacGibbon & Kee, 1967). The words written by Bowman’s shortly after Ferrer’s arrest in 1906 were eerily reminiscent of Cullen’s some twenty years later when he described the role of Bolsheviks in fomenting the trouble at Etaples: “The discontent of the people is profound, and the fire of their revenge is smoldering; it needs but a little spark to set it aflame” (Guy Bowman, Justice 29 September 1906, p.3). Bowman’s introduction to Ferrer had been initiated through Ward, who had provided him with letters of introduction. On Ferrer’s death, Bowman took up with Ferrer’s wife, Leopoldine Bonnard and their son, Riego (Sheffield Independent, 26 October 1906, p.9).

If Cullen was right and it was only tinder the ‘Bolshies’ needed at Etaples, they had it in spadefuls. Within weeks of Cullen’s article being published, the rancorous former Communist had moved across to the British Fascisti, whose party organ, The British Lion serialized it again in full that same summer.

The move by the British Fascists couldn’t have been better timed. Having an experienced former Communist spill the beans about Soviet meddling in the British Trade Union movement provided concrete evidence of Russian hostility. Again, all it needed was a spark, and the spark this time around came when over 200 uniformed and plain-clothed officers launched an astonishing raid on the All-Russian Co-operative Society building in Moorgate, London. As a result of the raid, Britain severed ties with Stalin’s Soviet Union and hundreds of Russian diplomats were expelled. In spite of the practical and diplomatic losses, the dormant will of the Communist Party in Britain received an indispensable boost, the inevitable backlash in the left-wing press seeing membership rise to 12,000 and re-energizing campaigns by radicals.

According to the spooks, Communists were now channelling their efforts into infiltrating military training bases. A tip-off from inside Arcos was passed to Mi5 claiming that it was now in possession of a Signals Intelligence manual from the base at Aldershot.

Soviet Signals

As strange as it may sound, the Soviet interest in British Signals Intelligence brought us right back round to Fallows’ old friend Percy Toplis and his Bristol Motor Gang.

12 months after receiving his punitive discharge from the navy and serving six months in prison, Toplis associate George Patrick Murphy found a way of resurrecting his Signals career by re-enlisting with the British Army’s Royal Corps of Signals at Chatham base (service no.2557074). This would have been remarkable enough in itself, where it not for the fact that Russian and British Communists were focusing their efforts on infiltrating the Signals Corps for the purposes of training and propaganda. This becomes apparent in the security service file of HMS Vivid activist and later Communist, Dave Springhall.

In the course of conversation with Captain Gravely about Communism in H.M Forces, particularly the Royal Corps of Signals, he mentioned that he had had a similar experience in a way of having to keep an eye on certain individuals in the Royal Corps of Signals. He told me a long story as to how KUDITCH, Secretary of the Russian Trade Delegation, was brought into contact with members of the Signals in Constantinople during the years 1922-23.

TNA, KV-2 1594

According to Springhall’s personal file, the Secretary of the Russian Trade Delegation had been brought into contact with members of the Royal Signals regiment as early as 1922 (TNA, KV2/1594). The application and development of Signals Intelligence also featured strongly in the so-called ‘Red Officer Course’ prospectus devised by Cecil L’Estrange Malone and reproduced at excitable length in the Home Office ‘scare bulletin’, Report on Revolutionary Organisations in November 1920. According to Malone’s 8-page manual, training in signals and communications would, in the event of a revolution, be absolutely essential in the Communist fight against the capitalists. Ex-servicemen were to be picked out and specialists like N.C.Os, signallers and engineers earmarked as potential leaders (Red Officers Course, November 6th 1920, TNA, CAB 24/114/68).

Recruiting from the raft of skills and talent in the Armed Forces was nothing new. Come the day of the revolution the rebels would need trained and experienced men capable of launching a credible offensive. The success of the Revolution in Russia owed more to soldiers and sailors than it did the proletariat. It really was now a case of, “Full Steam Ahead!” Militarizing the masses would be decisive.

The whole thing chimed neatly with an appeal made by Lenin in 1916, who similarly opined that ‘an oppressed class which does not strive to learn to use arms, to acquire arms, only deserves to be treated like slaves’. To take up arms against the bourgeoisie, the men would need to be given a gun and ‘learn the military art properly’ (The Military Programme of the Proletarian Revolution: II, September 1916). Men, Lenin went on, must ‘set to work to organize, organize, organize’. Within weeks Victor Grayson was repeating the very same mantra:

The men who have reaped the experiences of the trenches would come back trained to use guns and bayonets, and to act unitedly, and they would never again be satisfied with the old life of unemployment and want and hardship. They would make demands upon their governments … and knowing the value of organization they would be in a position to enforce their demands.

Victor Grayson speaking to the Wellington Social Democratic Party, Maoriland Worker, Volume 7, Issue 293, 27 September 1916

Within days Grayson had enlisted in the Canterbury Regiment of the New Zealand Army and was making his slow, patient way to Etaples.

The Arcos Raid and Manchester

Among those associated with the Arcos raid in Manchester were Frederick Ewart Walker of Longsight (near Hulme) and Fred Siddall of Higher Openshaw (KV2/1020, National Archives). According to Security Service files relating to their handler Jack Tanner, both men were leading figures in a Russian Espionage organisation being run by Cheka agent, Jacob Kirchenstein — aka. Johnnie Walker, the notorious Soviet master spy whose Arcos Shipping Company was responsible for transporting the six Young Communist League delegates to Moscow that same June.

Like Clarion Rambler Ward, Fred Walker had served as a senior member of the Amalgamated Engineering Union and the Metal Workers Minority Movement. By the time of his death in 1964 he was Manchester District Secretary of the A.E.U. The Chief Constable of Manchester, John Maxwell reported in February 1927, that although not a formal member of the Communist Party, Walker was an active revolutionary, deeply enmeshed in the inner workings of the British Socialist Party and Trades Union Congress. Just what radicalised him isn’t clear, but there may be clues in his service record.

Like Toplis’s Manchester buddy, George Patrick Murphy and Communist activist Dave Springhall, Walker had spent much of his service career at the HMS Vivid naval base in Devonport. The only real exception to this was a 12-month stint on the HMS Centaur 4, a C-Type light cruiser berthed between Chatham in Kent and Rosyth in Scotland. Built by Manchester’s Vickers Ltd, the ship would eventually play a part in allied attempts to break the Bolsheviks in Russia. The government’s decision proved unpopular with recruits, after betraying a pledge that any post-war involvement in the Russian Civil War would be mounted on a volunteer-only basis. A series of protests and strikes had broken out on many of the ships being earmarked for active duty in the Baltic. Among them was the First Destroyer Flotilla, the HMS Velox, the HMS Versatile, the HMS Vindictive and the HMS Wryneck. Men were demanding to be sent home, with many being sympathetic to the Bolshevik propaganda being distributed among sailors in the ports around Malta and Copenhagen. The problem was simple. A good proportion of the men had served alongside the revolutionaries on ships like the Rendi and Dwina when stationed at Archangel and Reval. During this time they’d all been comrades. Now they were meant to be enemies. A Gunner on the HMS Lucie would later tell The Worker’s Dreadnought how they’d observed first-hand the appalling conditions in which men of the Tsar’s Imperial Russian Navy were forced to serve and could well understand the turn of events that had given rise to the Revolution (With the Red Navy in the Baltic, Workers Dreadnought, 25 September 1920, p.5).

In October 1919, the tensions spilled over into full scale industrial action when 150 seamen of the First Destroyer Floatilla broke free from their ships at Port Edgar. Whilst most of the mutineers were arrested, some 44 men made their way to London to present petitions at Whitehall. They were arrested at King’s Cross and sent to Chatham Barracks. The code-name used to trigger the protest, bizarrely enough, was ‘My name’s Walker’.

Fred Ewart Walker had been demobilized to shore at the end of March 1919, and though its inevitable he would have witnessed and perhaps even participated in some of the protests, it’s unlikely he would have led any of them. It is nevertheless, a tantalizing prospect that Fred’s influence may yet have been felt at those events with the recycling of his (and Kichenstein’s) name.

Siddall, by contrast, was Walker’s spy at Armstrong Vickers. An entry in the KV2 security files claims that there was “nothing in the gun shop about which Siddall does not know” (KV2/3754, National Archives). For £5.00 a week, Siddall would pass the secrets on to Walker, Walker would pass them on to Tanner and Tanner would give them to Kirchenstein. At the time of Fallows’s suicide both men were the subject of a Home Office Warrant order issued by Scotland Yard. They could be observed but not interrogated. Their mail could be intercepted but under no circumstances could either man be approached. The benefits of questioning them now were thought to be negligible. Word from higher up the chain of command at Mi5 was that the men would “probably learn far more of what we knew of their activities … than we should learn about them”. If they waited just a little while longer they would “be in a position to link up the whole of this Russian Espionage Origination in the UK”, with the possibility of missing links in other investigations also falling into place (KV2/1391, National Archives).

Sometime between December 1926 and January 1927 — just weeks before Fallows went missing — there was strong indications that work on a new aircraft engine at A.V Roe was making significant progress. Word went around that Siddall had the plans and was keen to arrange a meet with Messer at a secret address.

Despite Walker and Siddall’s activities playing a key part in the government’s decision to launch the Arcos raid in the first place, no charges or arrests could be brought against the pair for fear of blowing the cover of undercover agents at work in the Manchester area (KV2/770, National Archives). By the end of 1927, Walker was living in Stretford just a twenty-minute walk from Clara Bellass, the supervisor at Armstrong Vickers who was married to Fred Bannister’s friend in Castleton, Harry Young.

The more one looks at the clusters of coincidences, the more plausible it seems that the worlds of Toplis and Fallows were colliding with the Manchester radicals. The links may have been based chiefly around certain names and certain locations, but there’s no doubting their regularity. Take the naval base at Devonport. HMS Vivid was at the centre of three seemingly unrelated lives: Toplis associate George Patrick Murphy, the Young Communist League’s Dave Springhall and his co-agitator George Crook, and Soviet Military agent, Fred Ewart Walker — each with solid links to Manchester. Sedition featured highly in the lives of all five, as did the Murphies, Fred having married into the Murphy family in 1929 (Caroline M. Murphy). Caroline’s brothers Alfred John Murphy (1901) and William Goodier Murphy (1897) would both enjoy distinguished careers in engineering with Professor William Goodier Murphy earning a CBE for his work at British Aerospace and the prodigious Cranfield Institute.

The links were patchy yet persuasive. As the world’s first industrial city, Manchester had been a hotbed of radical movements for years, whether it was the agitators of the Anti-Corn Law League or the rioting Wesleyan Chartists. As a result, its history was steeped in revolution. Marx was a regular visitor and Friedrich Engels made his home here. Without it, the pair’s Communist Manifesto might never have been written. Engels even lived out his days with fiery Irish sisters, Mary and Lizzie Byrne on Thorncliffe Street in Chorlton on Medlock, just minutes around the corner from the family homes of Bannister and Murphy some thirty years on.

The eventual raid on the Arcos offices came on May 12th, just days after Toplis detective, James Lock Cox was found dead at his home in Andover.

Peculiarly enough, a Secret Report passed to Mi5 director Vernon Kell in February 1927 explaining the activities at Arcos had been authored by an Edmund F. Cullen, who was at this time working for Soviet spymaster, Jacob Kirchenstein at the Russo-Norwegian Navigation Company. It was Kirchenstein who was running Siddall and Walker as agents in Manchester and it was also his company’s ship, the Youshar, that ferried the Young Communist League children to Russia that same June (KV2/818, KV2/1391). Cullen’s report arrived in Kell’s hands just weeks before Etaples Mutineer-turned-Communist, James Cullen published his similarly worded articles in the Glasgow Weekly Herald.

Arthur James Cook Returns. Harry Fallows Goes Missing

Extraordinarily, trade unionist A.J Cook arrived back in Britain from a trip to Moscow on the very day that Fallows and Stewart were noticed missing from their homes. Cook was the man at the centre of James Cullen’s claims about ‘Soviet Secret Funds’. It was Cullen’s belief that it was these funds, secured by Cook during his frequent trips to the Soviet, that were propping up Communist agitation during and after the General Strike. Cook’s return on the morning of New Years Day was accompanied by a series of fresh claims in the Conservative press. According to speeches he made in Moscow, Cook was promising not only to destroy the British constitution but to start a revolution. In Cook’s words, the government under Stanley Baldwin was ‘sitting on a volcano’. Subsequent attacks on Cook were made by George A. Spencer, Labour MP for Nottingham. A letter Spencer published in the Nottingham Journal on Saturday January 8th — the day that Harry and Marjorie’s bodies were discovered in the caves by Fred — was claiming that Cook had misappropriated £2,500 in relief funds intended for miner’s families (Miners Fund Mystery, Nottingham Journal, January 8 1927, p.3).

But this was just the tip of the iceberg.

In parliament far greater attention was being paid to the £1 million Cook had secured from Russia from the time the strike was called at the beginning of May till late November, when even the most persistent of the strikers had gone back to work. Officially, the money had been coming from aid donations made by Russian miners. If the cash had come directly from the Soviet Government, the TUC would have had to reject it.

Strangely enough, Cook’s mission to Moscow in the autumn of 1926 coincided with that of the Blaina Cymric Miners Choir who were there to drum up funds on behalf of their hard-up striking comrades back home. In their final week in England they had paid a visit to Sheffield, performing under the auspices of Dr Marion Phillips’ National Women’s Committee in Firth Park. A notice advertising the performance appeared under a series of Ramblers letters and updates in the Sheffield Independent. In Moscow the choir would be guests of the All Russian Trades Council.

During the 1920 manhunt for Fallow’s accomplice Percy Toplis, a man matching Percy’s description was seen entering a chapel in Blaina where he was greeted by Lower Deep Colliery miner and church deacon, Henry Coburn. The Dundee Evening Telegraph of May 13 had described how Toplis had pierced the Police net around Swansea and Cardiff and entered the remote and mountainous colliery district in mid-May. A prayer meeting had been in progress and Toplis had arrived in his customary muffler and seated himself at a back pew at Salem Baptist Chapel. He was heard telling Mr Coburn that he had found himself down on his luck, having walked here all the way from London. He was a member of a similar congregation at a Brotherhood Church in Hackney. For the duration of the service Toplis had sat nervously at the back twirling his cap between his fingers, not singing like the rest. An earlier sighting had placed him at the Gospel Mission in nearby Cross Keys. His Aunt Ruth, his mother’s sister, had been headmistress of a school in nearby Monmouth and Toplis had spent many a summer tramping cheerfully around these same mountainous districts in his youth. As there was no lodging house in Blaina, Toplis intimated that he would continue up to Brynmawr at the foot of the Brecon Beacons. A suggestion that he try the Police Station had been met with an emphatic, ‘No!’. The deacon is alleged to have handed seven shillings to him before Toplis went on his way (Toplis at Blaina, South Wales Gazette 14 May 1920, p.15).

The same Salem Baptist Chapel would feature in the news some eight years later when it was used as a rallying point by local Communist Brinley Jenkins during the so-called Blaina Riots. Salem Baptist Chapel had also been used by the family of Etaples Mutineer Jesse Short, who was born in nearby Nantyglo.

In his third article for the Weekly Herald, Cullen stated that he had evidence in his possession “to show conclusively that the Communist Party in this country is in league with the Soviet in Russia”. The article, published in March, fleshed out the details; four of the most notorious men in Russia — Schwartz (Chairman of the Soviet Miners), Gorbachev (the Miners Secretary), Akulff and the President of the All Russian Trades Council — were responsible for transferring the money to Cook. The cash hadn’t come from the hard-up Russian miners afterall, it had come from the Kremlin. Churchill had been no less cynical about Cook’s claims. Addressing parliament in mid-December, Winston thought it “extraordinary” that Russian miners, whose wages, he was assured, were one third less than British miners, had either the spontaneity or the resources to donate two and half times more than the whole of the British Trade Union movement.

On December 28th it was alleged that an amateur radio enthusiast in Bromley, Kent had picked up a speech on wireless receiving set on a wavelength of 1,400 metres. It was being made by a man speaking English in Russia. The speaker said that the first thing he was going to do when he got back to England to “work to his uttermost to create a revolution.” The Daily Mail only had one question on its lips; was this Mr Cook? (Daily Mail, December 28th 1926, p.10)

At the lower opening of Winnats Pass there is a volcanic plug called the Speedwell Vent. Cook’s claim that Baldwin’s Government was ‘sitting on a volcano’ and his dreams of an Anglo-Soviet pact with Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire miners couldn’t have been better geographically placed or better timed.

An Unusual Series of Coincidences

The mysterious death of Harry Fallows, the series of articles by Etaples Mutineer and former Communist James Cullen, the launch of a new anti-Soviet campaign by Home Secretary Joynson-Hicks, the re-appointment of de Courcy Parry and the sudden death of Superintendent James Lock Cox all took place with weeks of each other. That Castleton and the High Peaks were also facing a stiff election challenge from J.T Walton Newbold — the go-to man for boisterous agit-prop ramblers, the Young Communist League prior to William Rust — can only have cloaked the valleys and peaks of The Hope in a thicker red mist than usual that year.

The couple’s disappearance on New Years Eve 1926 coincided with two major fires in Manchester. The first was on Peter Street, the site of the legendary Peterloo Massacre where the 15th King’s Hussars had torn into a crowd of over 60,000 would-be revolutionaries some 100 years before. Over 2,000 party revellers were forced to flee the Free Trade Hall as the fire ripped through an adjacent building, bringing to an abrupt end the New Year festivities. The second fire broke out in the Sharples Building on the corner of Cannon Street and New Cannon Street. The building was at one time the home of Jeremiah Garnett’s Manchester Guardian, launched specifically for the task of championing the causes of the Peterloo protesters.

It may have been packed with symbolism, but if this had been a deliberate arson attack by rival fascists and not some darkly ironic coincidence, then it didn’t deliver much of a payload. Despite its continuing significance among the Clarion faithful and earnest young Reds an attack on the Free Trade Hall would have been an ambiguous and unpopular move. It had certainly been the venue of choice for New Year and Christmas Festivities among Manchester’s radical left and had even played host to Harry Pollitt’s series of Lenin memorials in 1924, but such crude and barbarous methods from angry young fascists in Manchester might easily have risked alienating ordinary people. An attack on the Young Communist League HQ in Openshaw would have sent a far more powerful message.

Despite 1927 terminating rather abruptly for Harry and Marjorie, the first few months of the year would provide critical events in the war on Revolutionary Communism.

A Hasty Burial

Within 48 hours of their discovery, the bodies of Harry and Marjorie were buried together in the one grave in St Edmund’s Parish Churchyard. The church, dedicated to a long dead Anglian martyr who had failed to renounce his faith after defeat by the marauding Heathen Danes, was situated in a hollow, little more than a mile from the wild, craggy hillside on which they died. A small crowd of relatives and well meaning villagers had assembled beneath the shadow of a spreading elm where the white surpliced clergyman, Reverend E.W. Hobson held a special graveside service in accordance with the law on suicides that forbade such things in church. Nothing was offered in the way of eulogies and no hymns were sung, the mourners having to make do with the energy of last month’s Christmas carols still echoing around on the peaks.

Harry’s coffin was lowered into the grave first, followed by his sweetheart Marjorie who was laid immediately on top of him. Beneath a tribute of gaunt trees and huddled sympathies, Fred Bannister bowed his head.

A subsequent search of the cave by locals, in the days prior to their burial, had revealed a woman’s brooch in rolled gold with a common red stone inset. Another bottle of poison was also found with the name of ‘Boots Cash Chemist Manchester’ on the label.

Among the more mysterious items were a large quantity of burnt papers. Although the fragments included a large quantity of burnt newspaper, clearly destroyed for warmth, some of the charred remains had been letters (Sheffield Independent 11 January 1927, p.6)

As the Sheffield Independent quite rightly pointed out, the couple were strangers to Castleton. They had no known associations in the village and there was no evidence to suggest that had spent so much as a night in any hotel or lodging house anywhere near the Castleton area. It was ascertained by Police that the couple were still in Manchester on the night of the 31st, but where they’d spent Saturday night, or any of the five or six days that followed, wasn’t unclear. It seemed improbable that they had spent the entire week sitting brooding alone in the cave or rambling around on the moors. Certainly not in winter.

Among the profusion of unanswered questions and riddles surrounding the death of the couple, one conundrum in particular stands out; not one single newspaper mentioned that the couple’s arrival in Winnats Pass on New Year’s Day coincided with the annual mass ramble organized by Ward and the Clarion Ramblers.

On Monday January 3rd, the Sheffield Independent had published a 600 word report describing the Clarion mass tramp around Castleton on the first Saturday and Sunday of the New Year. “Ramblers were everywhere”, they wrote. They’d arrived from all parts of the surrounding districts: “Sheffield, Manchester, Rotherham and Glossop — their eyes bright after tramping since morning”. At every bend in the winding path, and at each guide-post that marked the twisting lanes around Winnats, the press men had encountered a swarm of giddy youths “hatless and bare-necked”. GHB Ward’s name was sprinkled liberally throughout.

But by January 10th, the same newspaper was reporting that the area had been “comparatively deserted” at the time of the couple’s deaths.

How was this so? Were there concerns among leading figures in Sheffield that the couple’s macabre and mysterious passing might somehow tarnish the Clarion movement or aggravate tensions with local landowners? That readers might draw the wrong conclusions? It seems clear that the 17 year-old Fred Bannister had arrived in Castleton that first weekend in January as part of Ward and the Clarion Rambler’s New Year celebrations, but any speculation that Fred was part of an organized ramble is completely obfuscated in the press.

Lead rambler Ward though, was very well connected in press circles.

In June 1907, Ward’s close personal friend, Francesco Ferrer had been arrested for a second time in Spain. It was alleged that Ferrer and José Nackens, the editor of the revolutionary journal, El Modin had conspired to murder King Alfonso and the Queen Victoria Eugenie. Ward and the Sheffield Daily Telegraph launched a nationwide appeal in England to secure the mens’ release. Ferrer, in turn, made no secret of his appreciation. A letter, received by Ward, described the anarchists every intention to not let the summer pass without ’the pleasure of clasping the hands’ of his dear friend in Sheffield (A Letter from Ferrer, Sheffield Daily Telegraph 06 June 1907, p.7). Ferrer was to thank Ward and the paper’s editor Robert Haig Dunbar personally when he came to Sheffield in August, shortly after securing his release from prison.

Ward enjoyed an even closer relationship with the paper’s rival, the Sheffield Independent. The newspaper’s senior director and major shareholder was Sheffield’s William Wilson Chisholm, a ‘fearless and outspoken’ journalist who served as the city’s Justice of the Peace at the time of the Winnats Pass suicides.

Ward and Chisholm had forged their friendship through a shared passion for rambling — sharing committee duties on the board of the John Derry Ramblers, led by their friend and Clarion Rambler, John Derry, one time editor of Chisholm’s newspaper. Ward, Derry and Chisholm had been among the first to negotiate a right to roam agreement along Froggatt Edge with the Duke of Rutland in the 1924. The Duke had reneged on the agreement in the summer of 1926 after persistent abuse from overzealous youths among the Sheffield and Manchester radicals. That was the Duke’s official explanation, at least. Word on the ground was that the Duke had objected to Ward and Chisholm’s demonstration at Winnats Pass in support of the Access to Mountains Bill some weeks before.

The trio stayed close, with Chisholm printing and publishing Derry’s ‘Across the Derbyshire Moors’ book with a foreword and contributions by Ward from the Fargate offices of the Independent.

As the local and national press took their lead from the Sheffield Independent’s front page coverage of the Winnats Pass suicide story, it’s possible the connection was missed. Afterall, the only coverage Ward’s Clarion event had received had come courtesy of the Independent and the Telegraph.

The only people unlikely to have missed the connection was Chisholm’s Sheffield Independent, now under the management of Worksop-born editor, William Edward Bemrose. Why was no parallel being drawn between the two events? Fallows and Stewart had arrived in Winnats Pass on the weekend of Ward’s annual Clarion rambling event. The bodies were found by a regular rambler. In spite of all this, the author of the ‘suicide’ report on January 10th makes no reference at all to the couple’s arrival during the New Year Clarion celebrations it was reporting in considerable depth just five days previously.

But it wasn’t the only press mystery by any means.

There were also two significant differences in the reports published by the local newspapers. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph report featured the names of the Manchester ramblers, ‘Sunshine’ and ‘Ambrose’ — the mysterious Manchester ramblers who had accompanied Fred on the 2nd — and Mr and Mrs Young of The Island Gift Shop who Fred said he was visiting on the 8th. In the write-up by the Sheffield Independent, each of the names was left out.

These details were also left out at the inquest.

Fred Bannister had told the Sheffield Daily Telegraph that he had set off on his first trip to Castleton on Sunday January 2 with “two friends” ‘Sunshine’ and ‘Ambrose’. Neither of the boys was requested to attend the inquest and neither boy was mentioned. As subsequent newspaper reports proved, one of the boys, ‘Sunshine’ was well known in rambling circles. Given that the boy was one of the last people to see the couple alive, it seems curious that no attempt was made by the coroner to call him as a witness. There was also no mention of Mr and Mrs Young of The Island Gift Shop in Castleton. Fred had told at least one reporter that he was going to stay with the couple over the weekend but neither of Mr or Mrs Young were brought before the jury to corroborate the story. Fred simply revised his story: he had set off walking alone from Manchester on the Saturday and arrived at the cave around 5.00 pm.

A Light Goes Out, A Light Goes On

Irrespective of how the couple the died — by their own hand or by the hands of others — politicizing the tragic circumstances may only have risked triggering a violent backlash by the various radical groups amassing in Derbyshire’s valleys, or undermined, at the very least, the tremendous progress being made by Ward and his ‘Right to Roam’ groups. As far back as the 1880s, gangs of football supporters called ‘roughs’ would simulate attacks on fans to spark full scale riots at derby matches. It would be a trick perfected by proto-hooligan and fascist razor gang leader, Billy Fullerton and the infamous Billy Boys a few years later. Helping Bannister cook-up his unlikely explanation may have been a legitimate exercise in damage limitation, a way of averting a greater crisis — especially when news would eventually leak of Fallows’ connection to outlaw anarchist, Percy Toplis and his pals in the Cheetham Hill area.

The spark designed to cause a first-rate explosion may have simply been blown out, saving the reputations of the honest, hard-working men and women among them.

A lack of witnesses to the couple’s last 24 hours alive made the circumstances leading to their deaths impossible to determine. The telegrams delivered to Marjorie’s father and Harry’s sister Lily, could have been written by anyone, the couple could have been driven at night to The Pass and their bodies dumped, they could have been gassed or died after an evening of celebration bubbly laced with arsenic or strychnine — with the Lysol administered post-mortem — the options were endless. Modern forensics makes it possible to identify all toxic agents but in those days the bulk of poisonings simply went by unnoticed. The speed with which they were buried would have only added to the uncertainty. The only evidence that pointed to the couple being in Castleton on New Year’s Day was the testimony of Fred Bannister and the owner of the village gift shop who appears to have sold the cup that was used to drink the poison.

A week after the discovery of the bodies in the cave, Bannister’s friend ‘Sunshine’ reappeared in another press story. Two members of a Sheffield ramblers club had got into trouble on the snow-covered moors between Bleaklow and Edale. They fell in with a couple Manchester ramblers and one of them, the newspaper reported, “was a youth known as ‘Sunshine’, a companion of Fred Bannister who discovered the bodies of the man and the girl at Castleton” (Plucky Rambler Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 18 January 1927, p.8). Again, despite the best efforts of the press, the phantom rambler failed to materialize. ‘Sunshine’ emerges from the mist with his compass, loans it to a fellow rambler, flags down a passing car and saves the day. Was he for real or was he made up? It’s difficult to tell. Grafting ‘Sunshine’ onto another tale of adventure would certainly be one way of adding credibility to Bannister’s tale, should the locals or Police have been harbouring any doubts.

But if the couple had been murdered and their deaths made to look like a suicide, then why?

One clue might lie in the man that Marjorie’s father William Stewart was working for prior to arriving in Manchester. In the census of 1911, the 31 year-old coachman William and his wife Hannah Stewart neé Coe, are living at Nightingale Lodge in the grounds of Ellerbeck Hall, a handsome manor house some four miles south of Chorley in Lancashire. William’s employer here is Sir Arthur Dalrymple Fanshawe, Admiral and Commander-in-Chief of Her Majesty’s Royal Navy in Portsmouth. The house had been passed to him by his grandfather, the former Secretary of War Sir Edward Cardwell, a military reformist and close friend of Gladstone and Peel. Interestingly, records show that Fanshawe was personally responsible for the appointment of Intelligence Chiefs Sir Mansfield Cumming-Smith in 1909, and Hugh Sinclair in 1923.

Bottom: 1911 census showing Stewart family at the attached lodge

In the paranoid hurly-burly of the Great Strike, had Mr Stewart been recommended by his former paymaster as an informer? His job at Newton Heath Carriage and Wagon Works on North Road would certainly have placed him in a lucrative position for picking up news and gossip among its more radical workers from the Communist hubs of Cheetham Hill and Higher Openshaw. The father of Communist and Clarion Fellowship member ‘Charlie Openshaw’ (a close friend of Harry Pollitt) had worked as a wagon builder at the same company. The R.C.A union at the works had seen a steady rise in Communist Party members attempting to join for the purpose of disrupting it and every effort was being made to stave-off further infiltration. George Makgill’s Industrial Intelligence Bureau had done much to acquire intelligence on industrial unrest using well placed sources like these. Early warning systems were crucial in fending off strikes and maintaining a spirit of negotiation rather than rebellion among union members. At the forefront of this fight was the Economic League of National Propaganda, a head-strong coalition of high-ranking businessmen and industrialists, co-founded by an old naval colleague of Commander Fanshawe — Vice Admiral Reginald Hall. Now a tough-talking Tory MP, the former Director of Naval Intelligence and his group had been taking a leading role in opposing the General Strike with solid support from Fanshawe in the House of Lords and his son Guy in the House of Commons.

Once the head of a family had been recruited, it wasn’t uncommon for other members to follow suit. Had William’s attractive and seemingly very talented young daughter Marjorie Coe Stewart, assisted by the capable ex-Navy Reservist, Harry Fallows, been tasked with infiltrating the mixed-sex rambling groups who made up the Young Communist League?

It’s not as outrageous a suggestion as you might think.

A few years after the deaths of the couple, 25 year-old Manchester girl Olga Grey was recruited by Mi5’s Maxwell Knight to spy on Manchester Communist Harry Pollitt. The girl’s family home at 27 Montgomery Road in Longsight was just a mile or so from Bannister’s house in Hulme and the Young Communist League HQ on Margaret Street in Openshaw. Olga’s mission was staggeringly successful. As a result of her work, Soviet agent Percy Glading was arrested and his Woolwich spy ring smashed. Curiously enough, Glading had returned from his activities on the continent within weeks of Fallows’ death in January 1927 to join his place on the Communist Party of Great Britain’s Central Committee (Class Against Class: The Communist Party in Britain Between the Wars, Matthew Worley) .

There was another thing. Prior to their move to Manchester, Marjorie and her parents had lived on Church Street in the village of Adlington near Bolton. Just 200 yards down the road at 46 Market Street was the family of George E. Crook, the man at the centre of Communist agitation at the HMS Vivid naval base in the summer and autumn of 1920. Marjorie and George had been born within ten minutes walk of one another.

Harry’s ten page formal statement to Police shortly after being taken in for questioning over the Toplis affair had shown no small amount of savvy. He anticipates potential lines of enquiry in an agile, confident fashion and then just as nimbly heads them off. Whenever he describes his alleged meetings with Toplis the scenes and circumstances that he relates make witnesses practically impossible. Fellow soldiers at the camp have always ‘just left’ or ‘just about to arrive’. Had he fabricated the entire encounter to cover-up the part he and others may have played in the murder? One thing is certain, the man with a ‘jaunty air’ was clearly accustomed to talking himself out of a scrape.

Were the £50 notes Harry was alleged to be always flashing at neighbours the result of some fluky series of gambling wins or the spoils of a trusted crook or informer? This was no small change. In today’s money this would come to approximately £2,000 or more. A skilled labourer would need to work half the year to earn anything like this amount. If Fallows was on the take it was a risky business and one that could make either of them vulnerable to all kinds of pressure and intimidation 5.

A Thousand Black Balloons

Whatever the exact circumstances of their painful, untimely deaths and whatever tragedy had befallen them, the grim secrets of the cavern would be taken with them to their grave. Any thoughts they may have had in their last few minutes alive will never be known. There were no suicide notes and whatever personal items the couple had taken with them had all been burned in the cave. All that remained now were the possibilities. Setting fire to the letters had left their friends and families back in Manchester with only fragments of words — random signposts among the ashes. Snippets of phrases might still have been visible, but any explanation they may once have provided was now free from the burden of meaning. Only the words would ever remain. The truth would be lost forever.

But if it had been suicide, had there been a final rush of regrets? A sudden urge to run for their lives? Or had any remaining doubts been well and truly drowned by a good old soaking of gin? Like words that got stuck in the throat, or letters that got lost in the post, certain regrets may have been felt but not communicated.

When Harry’s torch finally went out, did the light go on for Marjorie? The intense black veil that would have fallen over The Pass in the evenings, is likely to have smothered all remaining optimism but maybe the girl had had second thoughts. What might we have seen in the darkness that day? A gradual shift from gutsy, youthful conviction to awkward compliance, perhaps. And from awkward compliance to screaming fear. What would have been the look on the pretty girl’s face when Harry finally offered her the cup of kindness?

And there’s a hand, my trusty fiere,

Auld Lang Syne

And gie’s a hand o’ thine,

And we’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet

For auld lang syne!

Perhaps there was no fear at all. In the last few moments of Marjorie’s life, maybe the common, practical things the 17 year-old had taken to the cave — the crocodile leather handbag, the green felt hat, the powder puff and manicure set — had already been discharged as trite, superfluous objects buried in the deep black seam of forbidden desires and failed Christmas wishes. These were things you could shove in boxes and pack away. Fragments of a life whose rules they were no longer bound by. What ‘things’ did she really need? Stripped of a reason to live, only misery could ever remain. Not even Nat Shilkret and his Ragtime Orchestra were going to be able to be fix things this time around.

In the final moments of consciousness, suicides are said to experience a much needed rush of blood to the face and a sudden surge of adrenaline will pump short extraordinary bursts of air to the lungs. In a bitter, tortured irony, their final desperate act would be the scream that proved they ever existed, the ‘scream that would fill a thousand black balloons with air’ and send them soaring over the moors of the Windy Pass 6. The summit of Mam Tor may have offered breathtaking views of the Hope Valley, but in the cool, misty twilight of the New Year it clearly offered little in the way of hope. Breaths would be taken for a final time. The cup of kindness supped clean.

What was the last sound the couple heard? Was it a sigh? A scream? The squeal of a late New Year’s reveller making merry in the village? Or the sound of the last shred of meaning in their impossibly short lives being torn like flesh from the bone.

The cave remains there to this day, as does Winnats Pass, demoted to playing host to a regular stream of Tour of the Peak cyclists and purposeful northern ghosthunters. By and large though, the various stories they have to tell are muddled up and the well-meaning spook investigator will end up calling out the names of tragic men and women who died elsewhere on the Pass, or died without any kind of drama, lying snoozily in bed at home. They wave their damaged radios earnestly at the walls of the cave, hopeful of picking up some meaningful spirit transmission. By and large though, the voices of the dead emerging from the garbled frequencies are nothing more than static, a torrent of white noise that would, as likely as not, lull the dead right back to sleep. The drips are still dripping and the mildly acidic water still pools in the same old places and evaporates in the same old places every year, gradually wearing down the sharp, urgent edges of the mystery in the same way it degrades the limestone.

The man with the jaunty air just laughs and the girl in the green felt hat adjusts her make-up in her cracked, vintage compact. They knew all about the ghosts stories, but as with most things that came whispering through the gates of the ‘windy pass’, there was probably nothing in them.

2 General Page-Croft was willing to go before a judicial enquiry and provide evidence taken on oath to make his case. “The party funds ought to be audited and a list of subscribers of over £500 deposited for inspection at Somerset House. Aspirants for honours ought to be reported on by the committee of the Privy Council.” The motion, read out in parliament, was seconded by Horatio Bottomley. Cash for honours, the pair alleged, was as perfidious as Lenin himself diverting large sums of money to assist Sinn Fein in Ireland, or buying the support of the Swedes (Party Funds and Titles, The Daily Mail, May 29, 1919, p.3). Victor Grayson vanished for good in September 1920. Several authors have accused Maundy Gregory, the man who arranged the sale of honours for the Government, of murdering him as a result of threats made by Grayson to expose him.

3 In the Winter 1986 edition of war magazine, Stand To!, Julian Putkowski, the historical adviser on the BBC’s Monocled Mutineer, acknowledged that the character Charles Strange was partly based on Victor Grayson. Strange appeared as the Socialist sidekick of Percy Toplis in the Alan Bleasdale’s Monocled Mutineer (see: Stand To!,Winter 1986, No.18, page.6). In 1907 Grayson was again very nearly arrested for inciting a mutiny, this time in Belfast in support of his Liverpool friend, James Larkin and Irish Dockers. It practically ended his parliamentary career.

4 In a deeply ironic twist, the HMS Centaur would play a role in securing Britain’s post-war Trade Agreement with Russia, after steaming to Constantinople on a prisoner exchange mission with Lenin’s Bolsheviks (Edinburgh Evening News 06 November 1920, p.5).

5 Former RAF engineer, Walter Fallows (born 1900, Salford Manchester) was in Russia at the time of the Metro-Vickers Affair (1933). He was one of a dozen or so engineers arrested on suspicion of espionage and sabotage charges. He discusses his experiences in a report entitled, Russia From the Inside published in The Horsham Times (Tue 26 Sep 1939, p.3). Colonel Allan Monkhouse of Mi6 was also arrested. Fallows would have been working at Westinghouses Works (Vickers) at the same time as supervisor Clara Ballas, the friend of the family that Bannister was visiting in Castleton. Walter Fallows had been sent to Russia by Vickers in 1929.

6 Scott Hutchinson, Frightened Rabbit, The Loneliness and the Scream

The Winnats Pass Mystery Part I: Death of Harry Fallows

Sources

Ramblers Grim Discovery: Winnats Pass Mystery, Sheffield Independent, January 10th 1927, p.1

Two Bodies Found In Castleton Cave, The Manchester Guardian, 10 Jan 1927 p.9

The Castleton Cave Inquest, The Manchester Guardian, 12 Jan 1927, p.2

Hull Daily Mail 10 January 1927, page 8

Cave Deaths, Daily Mail, Jan. 12, 1927

Festival Day For Ramblers, Big Tramp Over the Moors, Sheffield Independent, January 3 1927

Communism in Britain, 1920 – 39: From the Cradle to the Grave, Thomas Linehan, Thomas P. Linehan (see the chapter Communists at Play for coverage of mass rambling, pages 150-157)

Nonconformity in the Manchester Jewish Community, The Case of Political Radicalism 1889-1939, Rosalyn D Livshin

Aubrey Aaaronson, British Services Records, National Archives, Regimental No. 34146, 3rd Border Regiment

A Manchester Diamond Merchants Adventure in London, Manchester Guardian, 18 May 1912, p.12

The Lower Deck of the Royal Navy 1900-39: The Invergordon Mutiny in Perspective, Anthony Carew

The All Russian Cooperative Society (Arcos), KV2/818, National Archives, Kew

A History of the Peak District Moors, David Hey

Crime and Consensus: Elite Perceptions of crime in Sheffield: 1919•1929, Craig O’Malley, 2002

Death at Sheffield of Mr William W. Chisholm, Nottingham Journal 09 September 1935, p.11

Across the Derbyshire Moors, John Derry/GHB Ward, Sheffield Independent Press Ltd

Mutiny!, A Killick (Private No. 08907 RAOC), Spark, Brighton 1968

Red Schoolboys Trade Union, Sheffield Independent 21 December 1926, p.7

Votes For Fighting Men (Page Croft Campaign), The Times, Wednesday Sept 27 1916 p.5