The newspaper lying on the windowsill of the bothy said it all really: ‘Enchanting Secret Behind …’ Behind what? We may never know. Whether it was a deliberate move to preserve the spirit of a beautifully enduring mystery, or the fear of terminating some dream or hope that continues to sit loaded in my imagination like the pistol used in Percy’s getaway, I never did unfold the paper to reveal how the headline concluded. It probably sits there now, a taunting reminder of all we may never know about Toplis and the Mutiny in Etaples that this wily, cocky brigand may or may not have played a part in. Facts are scarce when it comes to Percy. He first entered the public consciousness in 1920 when for a brief spell he was the most wanted war deserter in England, tried and found guilty in absentia for the murder of taxi-driver, Sidney Spicer before being ambushed and gunned-down in Cumbria. 50 years later he was resurrected — this time as the hero of Bill Allison and John Fairley’s book, The Monocled Mutineer which painted a harsh and uncompromising picture of the riots that took place at the Etaples Training Ground in September 1917. He was and remains part-media creation, a patchwork of ideals and projections, a man fashioned from the slag of other men’s aspirations, a hero among unheroes, a cautionary tale derived from a less than cautious history. Anarchist? Activist? Spy? Violent criminal? I stroked my fingers over the moisture that a cooler, airish morning had left on the bothy window and signed it ‘Percy’. Within moments it had collapsed into a spiny, drooling scrawl. Against the bright green meadow outside, the word’s watery contrails took on a grim and faintly eerie dimension. I wiped my hand across it. The signature wasn’t in good taste, and I now felt slightly embarrassed. If I’d done the same thing in the steamy bathroom mirror back at home I knew the words would return the next time someone took a shower. As much as I had no interest in preserving whatever tasteless words I had teased on the glass, the basic shape of the words would remain. Some things were clearly not meant to be forgotten, however troubling or uncomfortable. When the BBC’s The Monocled Mutineer arrived on our TV screens in the mid-1980s, most of the working class population in Britain were holding out for a hero, someone with the nous and the bottle to stand up for the common man. Rioting was breaking out in prisons nationwide and justice was being demanded over the Westlands affair. We’d just had the Broadlands, Brixton and Handsworth Riots, and if the Miners’ Strikes wasn’t bad enough, we also had to endure Diego Maradona ‘handing’ a late winner to Argentina and putting England out of the 1986 World Cup in Mexico. I remembered a school friend telling me how his father had watched the game in a Drill Hall in Chesterfield. Two hundred or so colliery workers and their friends had mustered for a final rally before the last day of production was due to take place at one of the few remaining pits in Whitwell. The game took place on the Sunday and by Friday the men were out of a job. Several jokes went round the town shortly after that. If Margaret Thatcher’s final wish was to be cremated it was unfortunate that there would be no one left to mine the coal that would be needed to fire the furnace. And when she did die it would be the first time ever the 21 gun salute was fired into the coffin.

Unhappy is the land that needs a hero

Some years later I learned that the Drill Hall used by the miners had also been used by the 1st and 7th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters shortly before they left for the Somme. The men of Chesterfield sat alongside their Nottingham comrades waiting for the push that came in the Summer of 1916. 181 of the men who enlisted that day never came back. Not even the burly arm of Peter Shilton bursting from the goal-frame could have saved them that day, just as he wasn’t able to save the men of Whitwell during a similar Summer bloodbath some seventy years later. Percy had been born in Chesterfield before moving to Nottingham, and Shilton had enlisted under Clough at Nottingham Forest during those few short glorious years the team had triumphed over Europe. I tried to tease some meaning from these relatively harmless coincidences and curiosities, but the universe, god or whatever deeper purpose was shaping these random patterns must have been absent that day. They’d probably grabbed a bike and made off to the Lakes along with the last of the straws that I was grasping. As I looked back the bothy window I saw that the various watery contrails around the letters were now colliding. It was difficult to get any real meaning from it now. For many years, Chesterfield was a town in mourning. We joked that the miners should have been wearing black until someone pointed out that miners always wore black on account of the coal-dust, so nobody would ever have noticed. It occurred to me that this couldn’t have been more just; no one noticed the miners when they were there, so nobody was going to notice them now they were gone. As someone wisecracked, maybe the miners hadn’t really lost their jobs that day but had simply melted into the coal seam on that last day of production. When Bleasdale’s Monocled Mutineer finally premiered on August 31st that same Summer, the common man was poaching a fanfare that came some seventy years too late. As always, Private Percy Toplis just happened to be in the right place at the right time to lap up the credit. Like a ghost he came back to haunt the tight-lipped Tory Establishment and jam the circuit of England’s all too debilitating class-system at a time when us rough, unruly Northerners had willed it the most. What was that line in the play by Brecht? Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero? No. Unhappy is the land that needs a hero.

Technically this is not a bothy, which is just as well really, as Toplis, on the evidence currently available at least, is not a hero, and there is no firm evidence to suggest he even took part in the mutiny that handed him such fame and notoriety at the eleventh-hour. This particular boy from the blackstuff arrived on the colliery surface with a coal tub that wasn’t his own; a cuckoo in a nest of hornets. There is some indication he was in or around Etaples at the time that some of the riots took place. We have Edwin Woodhall’s memoirs to thank for that. Woodhall, a Special Branch detective with an ear for a good story, was tasked with rounding up military deserters in the aftermath of the 1917 mutiny and Percy Toplis was among the more violent and ‘ferocious’ of those he sought. Woodhall talks about his pursuit of Toplis in Detective and Secret Service Days (March 1929), and it is clear that he regarded Toplis as a dangerous and resourceful man. In 1915 Woodhall had joined the counter-espionage department of the Intelligence section of the Secret Police based at Boulogne. In September 1917, just as the mutiny was in full swing, Woodhall was transferred from Military Intelligence to the Military Foot Police at Etaples. Although he never states explicitly that Toplis was wanted in connection with the mutiny, Woodhall places him amongst the hundreds of ‘delinquents’ and ‘absentees’ in the caves and chalk dug-outs around Etaples the men had blithely dubbed ‘sanctuary’. After one ‘particularly exhaustive hunt’ Woodhall runs the deserter to ground in a cafe in Rang-de-Fleur. But any triumph is short-lived. Toplis is brought back to the compound but with the help of another prisoner makes a daring bid for freedom by tunnelling under the sand. In an account that has the improbable daring-do of a ‘Boy’s Own’ caper, Woodhall paints an absorbing yet fanciful picture of the scallywag eluding capture before any court martial and any subsequent execution can take place.

“(Toplis) was brought back to the prison compound for enquiry and identification. Unfortunately, during the night, he with another notorious character, who had the death sentence against him, tunnelled down under the sand of the barbed-wire compound … and broke out. I found one of the prisoners in an exhausted state near Berck Plage … but my real man had got away.” — Detective and Secret Service Days, Edwin T. Woodhall, 1929

But the accounts provided by Woodhall are not without their problems. If one was to believe everything he claims in his books, Woodhall would have been responsible for solving everything from the Jack the Ripper mystery to the assassination of Sir Curzon Whylie. There’s little question the detective was in Etaples at the time the mutiny takes place and operating in the capacity he describes (his war record corroborates this) but he’s also an accomplished storyteller. The detective may have been all of five foot seven, but on his tales he stood significantly taller. That said, if Woodhall had been lying about Toplis, you think he would have at least had the imagination to place him among the riots. Although described in no uncertain terms as thief, murderer, womanizer and deserter in the camps around Etaples at the time of the unrest, Toplis isn’t once placed at the scene of the riots. Instead he is described as being among the hundreds of men who had absconded in one way or another and taken refuge in the forest, dunes and caves around Le Touquet and Berck-Plage to avoid the fighting. In order to survive these men robbed civilians and army hostels. According to some military historians, if Percy had stuck with his existing regiment he would have been on his way to India, whose troopship, the RMS Orontes, was about to set sail that month. The Orontes, a troopship-come-passenger liner, subsequently found fame in Scarborough’s Peasholm Park as a 20 foot replica boat. Amongst a diminutive fleet of battleships and dreadnoughts, the liner floated around nervously, taking regular evasive action. Another of those taking regular evasive action was Percy. Woodhall describes Toplis as a ‘deserter’. If we were to take the detective’s account at face value then Percy wasn’t with his regiment. We don’t know where Percy was because his service records are not available. According to military historian Paul Reed, either the records haven’t survived or are still with the MOD. Dennis Brook’s history of RMS Orontes, Occasional Troopship of the Great War throws up another conundrum: by August 1917 the liner appears to have been back in commercial service and no longer in use as a troopship. Unless Toplis was masquerading an Australian dairy trader, it was hard to see how he could have been on that same boat in September.

“It would appear a quarrel took place one night between a “Tommy” and a Lance Corporal of the Military Police. The subject was one of the W.A.A.Cs. The row occurred through jealousy and terminated fatally, the “Tommy” being shot — I believe accidently — in the struggle. Immediately the news flew around the camp, and the troops rose en masse.” — Detective and Secret Service Days, Edwin T. Woodhall, 1929

There could be a perfectly straightforward reason Woodhall doesn’t mention the role played by Percy in the Mutiny: the British Government did not officially acknowledge the Etaples Mutiny until 1978. Prior to this there was no official confirmation it had ever taken place. The riots, and the role played by the deserters in those riots, were brushed swiftly under the carpet. Those who weren’t executed by a firing squad were dispatched immediately to the front where many would have died. There would be major offensives in Flanders and Ypres in November that year and major casualties could almost certainly be relied on. If you could rely on the plucky British Tommy for anything, it was their silence. A report in the Manchester Guardian dated February 13th 1930 pulls few punches in exposing the hubris and determination of the British authorities to suppress ‘the truth’ about what happened. The article begins with a fairly astonishing quote from R.H Mottram and Eric Partridge’s Three Personal Records of War, published just ten weeks before:

“The culmination of this period was that occurrence, chiefly disgraceful to writers about the war who appear in a conspiracy to conceal it, the Mutiny in Etaples. All countries engaged in the war had periods of widespread mutiny, a fact which should be noted and recorded, not hushed up … with the British it occurred … over some rumoured disagreement with the Police. I never knew the truth and perhaps no one knows it.” — Three Personal Records of The War, Scholartis Press, 1929

According to the witness account that follows, written from the perspective of a junior officer watching events as they unfold, the riots fell into two distinct phases: the “dispute” between the men and the Red Caps that led to the accidental shooting of Corporal Wood, and the change in tone and pace that occurred next morning, when a more organised mob of rioters, made-up chiefly of the “riffraff” who had settled around the outskirts of the camp, pushed back the troops controlling access to Le Touquet:

“Meanwhile a smaller mob came to the railway bridge over the river. The young officer in charge ordered the mutineers to go back or be fired upon. Some hesitated but the ringleader took no notice of the command and approached the youngster with a threat about the river being handy for drowning such puppies.” — Manchester Guardian, February 13th 1930

The ringleader was Jesse Robert Short, a serial deserter and former convict subsequently court-martialled and ‘put to death’ by firing squad in Boulogne on October 4th. He was thrity-one years of age. Significantly, perhaps, the junior officer backs up Edwin T. Woodhall’s claims that a further number of arrests had been made but that “many of the men “happened” to escape into the darkness.” Was one of those men mentioned by the junior officer, Private Percy Toplis? The junior officer is clear about one thing; there was the “justly indignant fighting soldiers” responsible for the initial slew of events and there was the “camp riffraff” on the other. The Guardian’s report provoked a short-lived barrage of letters; many of them printed in the Scotland, repeating much the same sequence of events. The riots started on the night of September 9th and continued for some four days. According to one former soldier writing into the Aberdeen Press and Journal, the riots were far worse than the Guardian report had portrayed and “might have had disastrous effects on the war had not the officers in charge taken the correct course” (Aberdeen Press & Journal, 17th February 1930). A letter mailed into New Zealand’s Otago Daily Times in March 1922, some eight years earlier, made similar allegations about a cover-up:

“Sir, – Although I have nothing but commendation for Colonel Stewart’s excellent book on the New Zealand Division, I cannot help expressing my surprise that certain important happenings in 1917 have not been recorded, especially as matters of far less importance have found a place in the book. For instance on page 53 mention is made of a deserter going over to the enemy. The lapse of this soldier is insignificant when compared with the mutiny in which 40,000 or 50,000 men were involved, composed chiefly of the New Zealanders.” — A.B Newland Snr Letter to the Otago Daily Times, March 6th 1922

The letter had been composed by Archibald Benjamin Newland Snr of Roxburgh. Newland had been a volunteer with the Church Army, whose casually-staffed canteen stood adjacent to the tea-room run by Lady Angela Forbes. The letter’s reference to a “copy of army orders sentencing Corporal —— of the Northumberland Regiment to be shot” not only proves Newland’s account to be authentic, it also suggests privileged access to the records of the camp’s Brigadier General. The Church Army Hut at Etaples at this time was under the day-to-day management of Ada Dorothy Blacklock, step-daughter of Baron Henry Horne, at this time serving as Lieutenant General of the First Army. Whether the letter was composed with the collusion of Lady Forbes or Dorothy Blacklock is likely to remain a mystery, but it does make one thing abundantly clear; the demands of the mutineers were satisfied in full:

“There was only one way to put a speedy end to this appalling state of affairs, and that course was happily adopted. Al the demands of the men were granted – the removal of the A.P.M (assistant provost marshal) and the “red caps” from Etaples, the cancelling of the out-of-bounds orders, a modification of the “bull ring” torture … and last, but by no means least, the assurance that no man was to be court-martialled for taking part in the mutiny. Numbers of men were court-martialled and shot at various times for inciting others to insubordination, so that it was not at all likely that the men would come to terms without this assurance.” — A.B Newland Snr Letter to the Otago Daily Times, March 6th 1922

Lady Forbe’s own memoirs, Memories and Base Details had been published the previous year and whilst her own account of the incident differs greatly in terms of detail, it is interesting to note that there are some curious verbal parallels between the two. With the exception of the letter published by the Otago Daily Times in 1922 and the Manchester Guardian report of February 1930, the British Public was to know absolutely nothing about the disturbances at Etaples for another 60 years. It’s easy to see why William Allison and John Fairley, authors of the 1978 book, The Monocled Mutineer were able to place to Britain’s most wanted man at the scene of the Mutiny in France. Percy achieved no shortage of notoriety for donning the garb of an Officer and regularly sported the monocle worn by the alleged ringleader. The only explanation that Woodhall provides for the interest that Special Branch took in this ‘military Ismael’ is that Percy was responsible for a ‘particularly brutal assault on an old French Peasant’ that took place within miles of the camp at Etaples. As you might expect, Woodhall makes no mention of any ‘mutiny’, but even experts are not convinced that any formal ‘mutiny’ as such took place. The series of volatile incidents taking place between August and September 1917 appear to have more in common with industrial action and labour strikes than any serious attempt to overthrow military authority. Conditions at the camp were pitiful, troops regularly having to endure grueling and degrading treatment at the hands of the non-commissioned officers putting them through their paces. A small contingent of those rioting demanded improvements to camp conditions and amongst the chaos and pandemonium certain threats were being served.

The saying “like master like man” was more than true in this case, for ever since Strachan had been A.P.M. the red caps in Etaples had become thoroughly offensive individuals, and no greater contrast could have been found than in the manners of the police in Boulogne and Abbeville, and of those in Etaples — Lady Angela Forbes, Memories and Base Details, 1921, Hutchinson & Co

Then came the first real excitement in the camp! Trouble over the police had been simmering for some time … I ran out to see what had happened, and found myself being swept down the hill to the new siding in the midst of an angry mob. It was nothing less than a man hunt that I was indulging in! — Lady Angela Forbes, Memories and Base Details, 1921, Hutchinson & Co

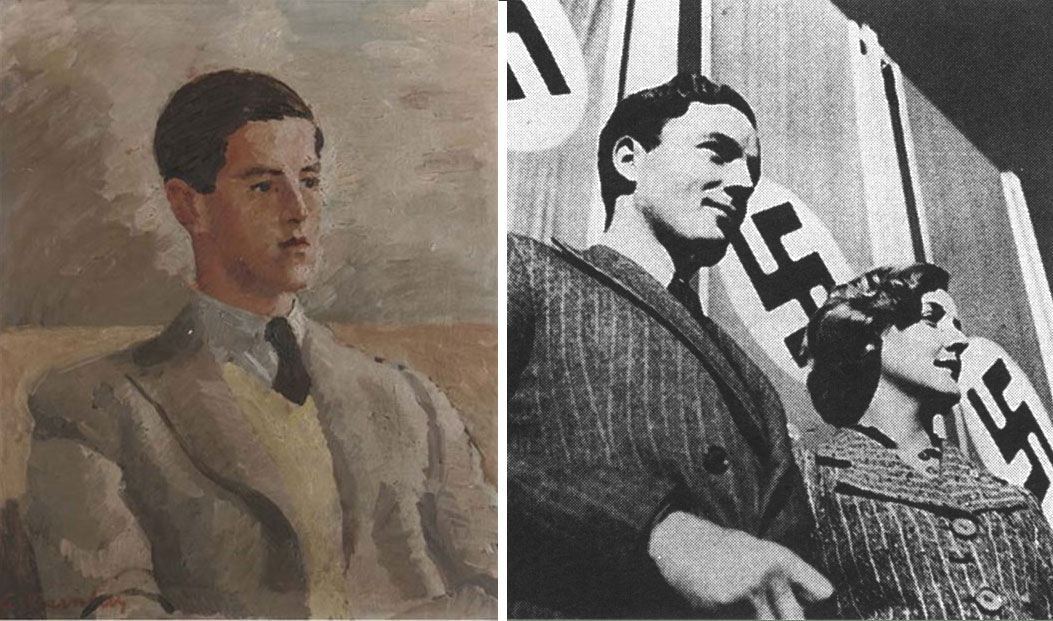

Woodhall mentions the simmering tensions over a fatal shooting of a young Corporal with the Gordon Highlanders by a Red Cap, and of a potential riot being averted, but he makes no mention of an actual ‘mutiny’. It’s completely downplayed, if not totally misrepresented in his memoirs. That Special Branch singled out Private Percy Toplis based on a single assault on an old French Peasant and a handful of petty crimes seems pretty implausible, but then it’s equally implausible that someone as cold-blooded and as habitually absent as Toplis would ever give a damn about the welfare and happiness of the troops. Toplis was forever reinventing himself. He would desert the army under one name and re-enlist under another. He’d talk with one accent and then, when need and circumstances arose, would just as casually switch to another. According to his family, Percy had shown promise as an actor as a child, taking part in local theatre with newly founded, Mansfield Ops, but it was nothing to match this performance. Some accounts of the riots had Toplis serving the demands for better conditions. Was this just another role he was playing? Was he looking to add a more worthy philanthropic layer to his ruthless and multi-tiered objectives? Like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s elusive anti-hero Jay Gatsby, Toplis’s attempts to add drama and a touch of stagecraft to his adventures revealed, to me at least, the lengths the rootless and dispossessed will sometimes go to, to produce any kind of personal narrative; it’s an identity Toplis craves. Uprooted and estranged from birth Percy was placing himself at the centre of his own evolving story: reconstructing his past, redrafting current circumstances and slowly bringing to birth an imagined future. When Private Percy Toplis arrived back in his hometown of Blackwell wearing a uniform and a gold-rimmed monocle he sold his story to Nottingham Evening Post. A hero’s welcome and champagne reception at the Miner’s Welfare followed, Percy regaling the crowd with his fanciful ‘Captain’s’ exploits. It was a move that can’t have sat well with the embittered hardline Socialists sharing his rations and swapping cigarettes in the ‘conchie’ sanctuaries around Etaples. By dressing as a British Army Officer, was Percy somehow withdrawing his opposition to the deeply repressive system that brought them all to France? He wasn’t the only soldier in the war posing as an officer, but he had branded those idle chevrons on his arm that little bit deeper than most. It was impudent and unruly, yes but it didn’t so much destroy the rules as distort them. It was part rejection, part homage, part surrender, part triumph. I wasn’t the first to have thought it, far from it, but if power was inherent in the very clothes on our back, could the things we wore ever be a place of revolution? We were tied in an ever tightening theoretical knot. The dashing young Captain, DCM we saw staring back at us in the photo wasn’t the face of freedom but of membership, not rejection but aspiration. The American essayist, Lionel Trilling was to call this ‘the socialization of the anti-social, the acculturation of the anti-cultural and the legitimization of the subversive’ but it all came down to one thing in the end; when it came to being dominated we were screwed. The revolutionary was locked in a destructive cycle that ultimately restored the dynamics of power by virtue of parody and simulation; damned if we did and damned if we didn’t. One thing was certain however; successful storytelling was at the heart of all revolutionary dramas and Percy (with Woodhall’s help) was writing one hell of a story. As with Gatsby this young and resourceful deserter was so full of artifice and artificiality that it’s really very difficult to know how much of what he showed was real. On this occasion, it really was a fine line between being nothing absolutely and absolutely nothing. You only have to look at the success of Isis to see that within extremist and revolutionary narratives there is enormous stock to be had in absolutes. Power is redistributed in strong, iconic images; its objective has to be clear, its future somehow inevitable and visually it must be compelling. To those at the extremities, the real has neither the clarity nor authenticity to challenge the status quo. If the fall of the Twin Towers in September 2001 proved anything it was that revolution had to be ‘unreal’. The steel girders may have weakened, the foundations may have shook, and the walls may have collapsed but it was the foundations of Western reality that were truly undermined that day. That Toplis wasn’t real made him all the more dangerous in my book.

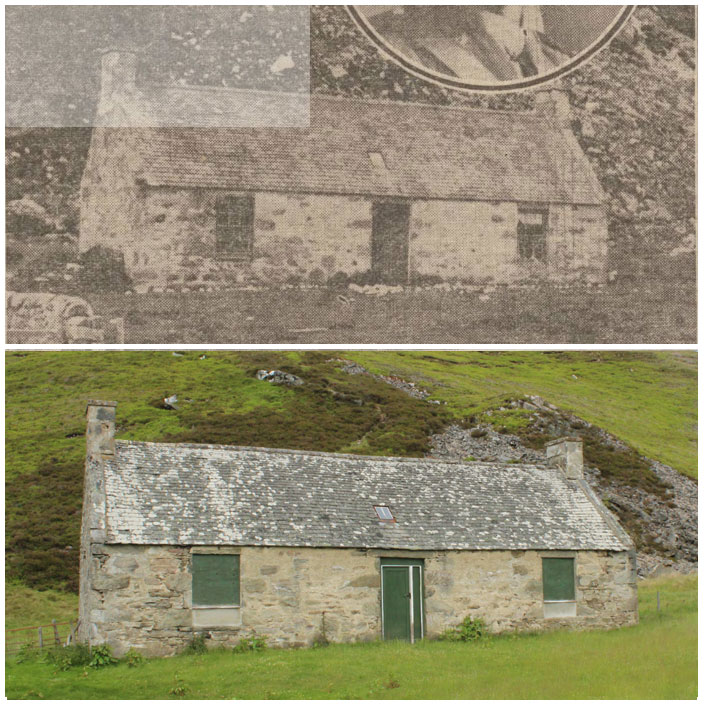

Anybody who has visited the bothy will know that it is pretty unevenly split between the bright and substantial ‘hospitality’ room and the cramped and darkened ‘side-room’. Whilst shutters have been crudely applied to the windows of both rooms, a small skylight transforms the former. The atmosphere here is one of orderliness and practicality. The floor is cleanly swept, the improvised furnishings are arranged neatly and a utilitarian calm and purpose prevails. Not so the darkened ante-room. The levity of the sun hadn’t pierced those shutters for years and it was only the feeble flash of my smart-phone that revealed the freakish scrawl of worshipful signatures that plastered the room from floor to ceiling. Not being able to see it in its entirety leant it a mystery and persuasiveness far greater than the sum of its parts. A scruffy, flaccid sofa sat on one side, and several other unspecified furnishings that may have been boxes collapsed about my feet as I stumbled around in the dark. Was this the room that Toplis had slept in? Was it here that we had tethered his ghost?

Tinker, Toplis, Soldier, Spy

At the time the mutiny was taking place in France, Britain was in the grip of a paranoia about German Spies and Russian anarchists. It saw them everywhere. In his 1922 book Queer People, Intelligence Chief, Sir Basil Thomson offers his own sardonic take on the affliction:

“I began to think in those days that war hysteria was a pathological condition to which persons of mature age and generally normal intelligence were peculiarly susceptible … I remember Mr Asquith saying that there was nothing so completely proved as the arrival of the Russians. Their landing was described by eyewitnesses at Leith, Aberdeen and Glasgow; they stamped the snow out of their boots and called hoarsley for Vodka at Carlisle and Berwick-upon-Tweed.” — Queer People, Basil Thomson, 1922

Even before the Great War, writers like Erskine Childers, author of The Riddle of the Sands and William Le Queux had been writing imaginatively of a sophisticated German intelligence network laying the foundations for an invasion of Britain. Hysteria aside though, by April 1916 a total of 11 German Spies were rounded up and executed in Great Britain, and Scotland featured prominently. In 1915 two spies, George Traugott Breeckow (aka. Reginald Rowland) and Lizzie Wertheim (operating under several Toplis-like aliases) were believed to have been meeting at the Station Hotel in Inverness (now the Royal Highland Hotel just off Academy Street). Coincidentally or not, Inspector Hubert T. Fitch, the commanding officer of Toplis detective Edwin Woodhall, was instrumental in their capture. Breeckow was subsequently executed at the Tower of London on 26 October 1915. Wertheim on the otherhand was sent to Broadmoor criminal asylum. Prior to taking refuge in the bothy, Percy had blagged a job playing piano at another hotel just minutes around the corner. An edition of a local paper records that guests at the small Temperance Hotel in Inverness city centre found his “conversational powers” attractive and had asked him to entertain. It’s a peculiar story to say the least. His stay in Alford on May 3rd suggests he arrived in Scotland via Aberdeen. From here he makes his way to a ‘little hut’ in Strathdon, spends a few days in Tomintoul, before finally landing work at Dunmaglass – a forestry estate owned and managed by the McGillivray family, the mighty Highland clan who had made such an heroic stand at Culloden as part of the Jacobite rebel army. Prompted by either business or an itch to move on he arrives in Inverness on May 11th. Signing the guest book as ‘G. Waters’ he tells guests he is a jobless piano-tuner and has recently spent time ‘in Russia’. Asked about his activities in the area, Toplis says he had landed the post of caretaker at the nearby Northern Meeting Rooms. He had just been to see the agents. When the owner asks about his female assistant, he remarks that she will be arriving shortly from Aberdeen, and makes a trip there the following day. The details on his stay at the Temperance Hotel vary little in each of the local reports but two details in particular stand out: Toplis was not travelling alone and he had a brown paper parcel that he was ‘most concerned’ about. When he arrived back at the hotel one night without the parcel the hotel keeper decided to quiz him about it. Toplis confessed that he had left the parcel in a nearby public house. He’d been engaged in some business matter and had just received a telegram at the post office. The keeper takes up the story:

“To cut a long story short he was here till Friday on and off. It was like this, he explained. we had known on his own confession that he had been out having drinks. He asked me to keep him over the weekend. Then I put it to him quite bluntly: “It strikes me there’s a mystery about you, young man”.

“Do you think he was pressed for money?”

“I think so. He wanted to get his coat to sell. He said he had brought his cabman with him and that he was outside. I saw the man whom he had brought. He was certainly not an Inverness cabman. This man was wearing a dark bowler hat, and had all the appearance of a stranger. Both of them stood very erect.” (The Highland News, June 1920) When the coroner inspected the quality of his boots at the Inquest in Penrith he remarked that that there was barely any wear on them, suggesting the victim had enjoyed regular periods of transport. This is completely at odds with the depiction of Toplis as a wandering itinerant, rambling randomly around the Highlands. Was someone sheltering him? Who was his companion? Did the Police ever follow this up? What brought him so urgently to Inverness? Let’s look at it another way; Toplis lands a job on an isolated farming estate in Dunmaglass, some fifteen miles south of Inverness and leaves it to spend four days in a densely populated city with all the potential pitfalls and sightings this might present. This would be a substantial risk for a wanted man. What had prompted the move so urgently? A telegram or a tip-off? True to form, Toplis departed the hotel without paying the bill and found alternative work, first at MacDonalds Mill in Inverness, then Finnies Mill in the Muir of Ord and then finally as a woodcutter on Banffshire’s Delnabo Estate, just a mile or so from the Tomintoul bothy. Contrary to popular belief, Toplis had begun his journey in Tomintoul. He had clearly not just spent his few remaining nights there. Did Percy’s frequent trips to Inverness and the North of Scotland give Woodhall and the Secret Service reason to think he was a spy or agent provocateur? It’s certainly possible given the taut, suspicious climate at the time. Several other German Spies captured during that same period had been had their bases in Scotland: Haicke Janssen, Willem Roos and Ludovico Hurwitz Y Zende – both of the former spending significant periods of time in Inverness. Breeckow and Wertheim were not an isolated case. A total of 18 German spies were arrested (and subsequently executed) during the first 12-months of the war. The son of a Russian piano manufacturer, George Breeckow had been born in Stettin, Germany before travelling to America. Here he lived as Reginald Rowland, pianist and piano salesman, only returning to Germany in May 1914. Back in Germany he landed a post at the Bureau of Foreign Affairs. A transfer to the Kriegsnachrichtenstelle Antwerp — the German school for spies — immediately followed. His plausible American accent, polished manners and considerable wealth made him easy to embed among the military elites of Whitehall. On arrival in London he booked into the 630-room Ivanhoe Hotel on Bloomsbury Street. This would be critical to two objectives. On the one hand it would give him access to gossip leaking from the Admiralty Building and War Office in Whitehall and on the other he could garner support from the well-heeled clique of parlour subversives who’d taken up residence in the Bloomsbury area. His cover as pianist and piano salesman for the Vandervoort Piano Salon would bring him into contact with only those people who could afford this particular model at this time: the Officer class and gentry (interestingly, professional musicians accounted for a significant proportion of the ‘Kriegsnachrichtenstelle’ spies arrested at this time). But it was the lowly and uneducated Lizzie Wertheim who did the field work. According to British Spy Chief, Basil Thomson in his 1922 book, ‘Queer People’, Wertheim would go to Scotland, hire a motor-car, and drive around its various ports picking up gossip about the Grand Fleet. Her approach to naval officers was so lacking in subtlety, however, that it brought her to the attention of Special Branch and before long she was placed under surveillance. Toplis, on the otherhand, was not so lacking in guile. Not only was he a master of disguise and a resourceful and consummate actor, he also was in the habit of using aliases, faking IDs and used the kind of counter-surveillance tactics frequently used by professionals to dodge being tracked. His flight from Tomintoul is characterized by tried and tested manoeuvres. He was sticking methodically to certain rules. His ‘cleaning run’ from Alford to Aberdeen included regular changes in direction. He would change his mode of transport, talk to as few people as possible, abort journeys abruptly, getting off before intended stops. All of these were reliable counter surveillance measures, and all would require training.

“Another statement made by a lorryman was as follows … I was driving my employer’s lorry along Great Western Road in the direction of Mannofield when a man held up his hand a s signal to stop … he asked me for a lift to Bieldside — ‘Going to Bieldside’, 04 June 1920 – Aberdeen Press and Journal – Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire, Scotland

What business Toplis had in Bieldside is anyone’s guess. The lorry driver goes on to say that he was only able to take him as far as Craigton Road. Here the driver stops. He tells him that he should be able to flag down another car to Bieldside but Toplis reassures him it’s not a problem. He says he recognises the area and will walk the rest of the way. Toplis starts walking in the direction of Cults and disappears down Morningside Road. If this was his first trip to Aberdeen, then how did Toplis know the area? Bieldside was and remains one of the wealthiest districts in Scotland. The respected architect, Alexander Marshall Mackenzie was based here and the family of Ruth Roche, Baroness Fermoy, the Maternal Grandmother of Diana Princess of Wales were also residents here at this time. His two bookend stays in Alford are also interesting. Alford is the Clan Base of the Forbes family. The family of Etaples ‘canteen lady’ Lady Angela Forbes, dismissed from the camp for her disruptive influence on the troops, had their home in neighbouring Asloun. What was Toplis up to? Did he have old scores to settle? Was he trying to solicit allies? Trying to drum up a defence with the help of the Forbes? Interestingly, another member of the Alford Forbes family, William Forbes-Sempill (very nearly tried for spying for the Japanese in 1941) was active in several anti-Semitic associations, including the Anglo-German Fellowship, the deeply mysterious Link organisation and pro-Nazi Right Club. Lady Angela’s nephew, ‘Hamish’ St. Clair-Erskine became the lover of Tom Mitford. Tom’s sisters were Diane and Unity Mitford whose devotion to Adolf Hitler needs little elaboration.

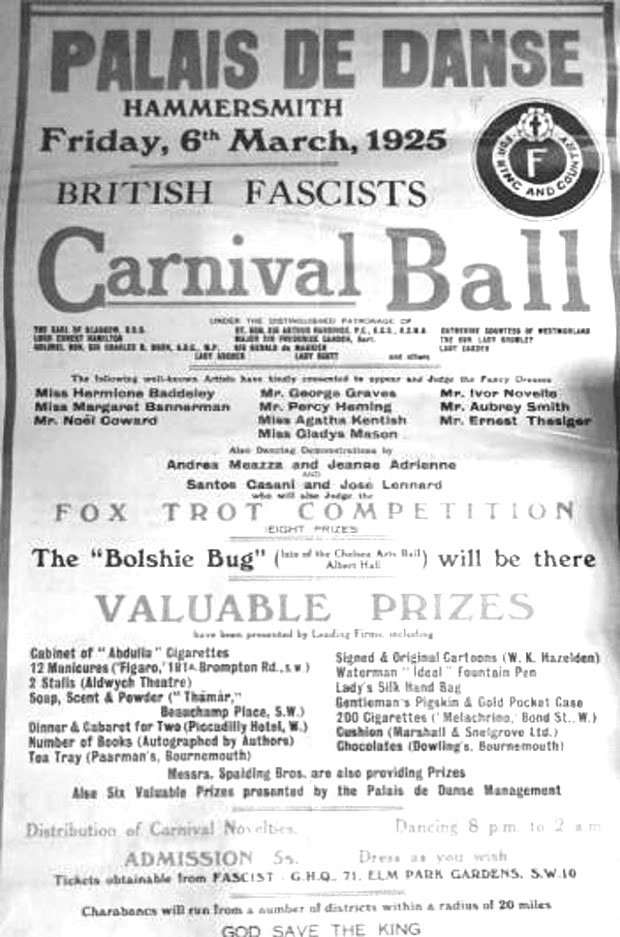

But there was another twist. Lady Angela’s sister, Lady Sybil Mary St-Clair Erskine had been made Countess of Westmorland on her marriage to Anthony Mildmay Julian Fane in 1892. Curiously, the ambush on Toplis had been organized on the ground by Chief Constable of Westmorland, Charles De Courcy Parry. Like the Fanes, the Chief Constable’s family were similarly devoted to a lifetime of hunting and shooting. And here was another thing; after the death of Lady Sybil in 1910, Anthony Fane married Catherine Geale, who in 1925 as Catherine Countess of Westmorland co-sponsored a fundraising ball for the British Fascists. The event was held at the Hammersmith Palais de Dans.

The event organizer was Rotha Lintorn-Orman, founder of the British Fascisti and whose Scottish Women’s Hospital Corps had served in Percy’s Royal Army Medical Corps in Slovenika in 1917. Like Percy, Rotha had been invalided out of the corps with malaria that same year. Was the reference to the ‘Bolshie Bug’ on the poster for the event a saucy sweep at the ‘Bolshie’ Chelsea Arts Club and its left-wing clientele? The Chelsea Arts Club was based on Old Church Street in Chelsea and boasted a healthy left-wing membership base. Those associated with the Club included the Rennie Mackintoshes, Scottish dance queen, Margaret Morris and Communist Kodak King, George Davison, whose funding of Keir Hardie and the South Wales Miners’ Federation (as well as the quasi-anarchist Workers Freedom Groups in Gateshead, Bristol and the Rhondda Valley) had already brought him to the attention of Special Branch. At this time Morris had set-up her own tri-monthly ‘Margaret Morris Club’ on Flood Street, Chelsea. The Club had become something of an ‘outpost’ for all the artists and intellectuals who had previously coalesced at Soho’s ‘1917 Club’ (frequented by none other Oswald Mosley). The Chelsea Arts Ball (hosted annually at the Albert Hall on New Year’s Eve) was one of the most scandalous events on the calendar, a fancy-dress extravaganza brimming with immoral intent and voluptuous barbarity. Sponsors of the Fascisti Ball by contrast, included Patrick Boyle, 8th Earl of Glasgow (who had witnessed Bolshevik brutality first hand) and British Diplomat, Sir Arthur Hardinge. The image of the benign Lady Angela contrived by the Bleasdale 1985 BBC TV drama was slowly beginning to fade. As I boy I had found to my cost that if you left anything burning long enough, the embers of the fire would turn from red to white, and that the endearing first shapes of the flame were nothing when compared to the white hot properties of the coal. Contrary to expectations Lady Angela Forbes was not some banner-waving socialist but every inch the Militant Conservative out of whose soft femine features would soon be carved the firmest of fascist mugs; back to black, as it were, for the coal.

If I were a Prime Minister I should promise nothing, but I should spend my time in devising means to reduce this strangling taxation and unemployment, and if I succeeded even a little in that direction my tenure of office would be secure. I should reduce Government staffs to a practical minimum, and I should order other people about not be twisted round other people’s fingers. I think I should know that Kharkow was not a general, even though I could not put my finger exactly on its situation on the map. I should bind our colonies to us with bars of steel ; I should make the firmest alliance possible with France ; I should fight alien labour to the death ; I should squash the Jewish invasion by every means in my power, even if it meant having fewer new frocks. But then I never shall be Prime Minister — Lady Angela Forbes, Memories and Base Details, 1921, Hutchinson & Co

James Cullen, sentenced to one year’s imprisonment for the part he played in the Etaples Mutiny, similarly found his way into the bosom of British Fascism. Born in Pollokshaws in Glasgow in 1891 and a miner by trade, Cullen’s regular war-time cycle of insolence and desertion came to a head in September 1917 when the mutiny was in full swing. Having already served sentences for an assault on a female worker and breaking out of barracks, Cullen was charged by Brigadier Thomson with ‘disobeying lawful commands’ and ‘using threatening language to a superior officer’. He was sentenced to one year in prison. However, the sentence was duly suspended and the soldier dispatched immediately to the front. What better way of purging the ranks than by sending them all to Passchendaele? But Cullen didn’t die at Passchendaele. Wounded he arrived back at Etaples, where he convalesced awaiting trial. For reasons that are not entirely clear it was decided that no further disciplinary action would take place and in August 1818 Cullen was approved for immediate return to Scotland where his mysterious demobilisation (and wrongful, arrest) became the subject of debate in parliament. The route he embarks on next is quite extraordinary, and made all the more extraordinary by having never been acknowledged previously. Within a few years of leaving the army, Cullen becomes a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, organizes hunger marches from Glasgow to London, and then, under the stellar guidance of notable Clydeside Marxists, Harry McShane and John Maclean (similarly born in Pollokshaws) becomes an active and respected figure in the National Unemployed Workers’ Movement. However, concerned by the undue weight of Soviet influence in the NUWM and an increasing lack of faith in Maclean, Cullen begins his move away from Communism, and within years he has become Secretary for The West Scotland Association for the Abolition of Communism. An encounter with Baptist Minister Peter McRostie of Tent Hall, further revolutionizes his way of thinking and by July 1927 he is writing an article in the British Fascisti periodical, The British Lion lifting the lid on a contingent of Bolsheviks at work in Etaples at the time of the riots:

I was approached by a prominent Communist agitator, who asked me what part I would take in getting the troops to mutiny. There was a small council of action set up and we set about doing everything possible to get a general rising… the councils of action, of which I was one, were giving instructions through under channels. The revolt lasted three days, at the end of which a truce was come to between the General Officer Commanding and the rebel troops. I was one who refused point blank to recognise the truce and carried on with a small band of irresponsibles. Eventually we tried to rush the guard one night, but were repulsed. I was captured and made a prisoner — James Cullen, British Lion

George Bernard Shaw once said that, “the moment we believe something, we suddenly see all the arguments for it.” Suddenly the world changes and events we have experienced previously are transferred to the source code of an executable program that is only ever designed to calculate one particular outcome. I was experiencing much the same phenomenon now. Were these the candid insights of one seriously pissed-off mutineer, unburdening himself of the truth after all those years, or the skewed, revisionist strokes of a belligerent would-be fascist seeking formal membership of a new and very exclusive club? Cullen was something I would come back to.

The Cross Keys Mystery

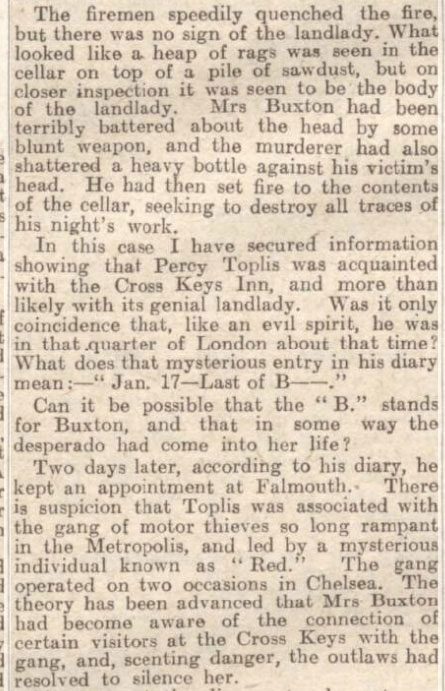

In the end it turns out that detective Woodhall may have had every reason to be suspicious about Private Percy Toplis. In January 1920 Toplis had been a suspect in the murder of Mrs Frances Buxton, capable and affluent landlady of the Cross Keys tavern in London. According to a report published by the Daily Post in June, Buxton had been ‘terribly battered about the head by some blunt weapon’ in the cellar of the property. The perpetrator had then set the contents of the cellar on fire. The body of Frances was found partially burned after smoke was found issuing from the building. There were no signs of a break-in leading Police to ascertain that the lady knew her attacker. The reporter tells the reader that he ‘secured information’ that Percy Toplis was acquainted with the Cross Keys Inn and ‘more than likely with the genial landlady’. Another of the suspects was Charles Rennie MacKintosh, the famous Scottish architect. Mackintosh admitted to an affair with the attractive hostess and was a regular at the tavern — a popular haunt for the louche bohemian radicals, anarchists and writers less-than affectionately known as the ‘Chelsea Set’. According to her estranged husband in Bexhil-on-sea, Frances was a bit of a radical herself. An enthusiastic suffrage supporter and Socialist, Mr Buxton describes his wife as an intelligent and ‘strong-minded’ woman with a string of successful bars and hotels to her credit. What part Toplis played in her life is uncertain but reports at the time suggest he was one her many companions and was in receipt of gifts and ‘remuneration’. On January 17th 1920, the day of the murder, a sinister entry in Toplis’s diary reads simply, “Last of B …” The last of Buxton?

Mackintosh, however, had already come under the scrutiny of the Police. During his and his wife’s self-imposed exile in the costal village of Walberswick in 1915, Mackintosh was suspected of being a German Spy. A bundle of letters he had written in German were found by Police and it was feared he had used his lantern to signal messages out to sea. The letters at the centre of the probe were addressed to Hermann Muthesius, a German diplomat and author who had been promoting the British Art and Craft movement to audiences back home. Several years prior to the war Muthesius had served as cultural attaché at the German Embassy at 9 Carlton House Terrace, but between 1912 and 1914 things took a more radical turn when he joined the propaganda committee of pressure group on social reform with Karl Liebknecht of the Spartacus League, a Marxist revolutionary movement organized in Germany during the first years of the war. One prominent member of the League was Rosa Luxemburg, a naturalized German citizen who had been brought to the attention of Special Branch when she was among the 300 or so delegates attending the Fifth Congress of the Russian Social Democrats in Whitechapel, in the East End of London in 1907. Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin also attended (see: A Political Family: The Kuczynskis, Fascism, Espionage and The Cold War, John Green, 2017). Whilst modern historians seem keen to laugh it off as wartime paranoia, it is clear that Mackintosh and his India-bound friends Sir Patrick Geddes and Annie Besant were appearing on the radar for their various subversive alliances — not least with the Irish Republicans. Their friendship with Suffrage leaders Ada Neild Chew and Rebecca West was damaging enough, but ‘Toshie’s’ increasing intimacy with French anarchists like Paul Reclus and early Scottish Nationalists like James Pittendreigh MacGillivray and Hugh MacDiarmid must have only deepened concern at Whitehall; their Scottish Nation anthology of poems combining dangerous intellectualism with a lyrical Jacobite twist. MacDiarmid (real name Christopher Murray Grieve) had, like Toplis, served during the war in the Royal Army Medical Corps. Did they ever encounter one another? Who knows. One thing is certain however; both men had enlisted at the same time, both had completed training in England at the same time and both had served in Salonika. As Sergeant-Caterer of the Officer’s Mess perhaps MacDiarmid had come across Percy in full theatrical costume; monocle firmly in eye and Officer’s ‘swaggering cane’ gripped at his side. Whatever the truth of their engagement it’s interesting to note that both men had contracted malaria in Salonika and both were invalided out — possibly within weeks of each other. Curiously, both convalesced in Scotland, Toplis handling light munitions work in Grena Green and MacDiarmid returning to Montrose. Like Toplis, MacDiarmid had been an exceptionally bright pupil whose education had been cut short by a temporary spell of crime. Not that it hampered his learning any. Immediately prior to the war MacDiarmid had landed a job as a newspaper reporter at the Monmouthshire Labour News in Wales, set up as mouthpiece for the South Wales Miners’ Federation (or ‘The Fed’ as it was known) and controlled by Keir Hardie — former member of the Scottish Land Restoration League and foundation stone of the British Labour Party. The strikes and riots MacDiarmid covered during this early phase of his career he would later describe as ‘war reporting’. From his arrival in Ebbw Vale in 1911 until the very first whispers of war he wrote of the resistances of the coal miners. ‘It’s like living on top of a volcano here,’ he wrote home. The Tonypandy Riots of 1910 and 1911 had spilled right across the Rhondda Valley, and Winston Churchill, as Home Secretary, had sent in Calvary troops and mounted Police from the Met in a characteristically heavy-handed attempt to restore order. The riots were ostensibly the culmination of a bitter industrial dispute between the workers and mine owners, but in regions like Tredegar the skirmishes and assaults took on a cynical and unpredictable anti-semitic edge. The windows of Jewish shops and homes were smashed and 20 Jewish businesses looted. Soon there were similar disturbances taking place in nearby towns like Ebbw Vale and Caerphilly. Another resident of Ebbw Vale at the time of the ‘Great Labour Unrest’ was Jesse Short, the only British man ever executed as a result of the Etaples Mutiny. Short had been born in nearby Bedwellty and spent the first years of the 1900s in Nantyglo and Mountain Ash, home of Emrys Hughes, a noted pacifist during the war and firm associate of Labour Leader, Keir Hardie. A coal miner by profession, Short had attempted army life several times in his 27 years alive, enlisting first with the Welsh Regiment in 1905, then with the 3rd Wiltshire Regiment in 1907, the Durham Light Infantry in 1914, before his eventual and ill-fated call-up in 1915 for the 26th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers. Invariably his periods of service lasted little more than weeks. He was a regular deserter even in peacetime and his stint with the Wiltshire Regiment ended abruptly on charges of theft. In 1909 Short was arrested again, this time for the robbery of 37 watches, 2 lockets and 1 bracelet from the shop of John Edward Watson in Hereford. He was sentenced to 15 months hard labour. Whilst there is no evidence he and MacDiarmid ever met, it’s curious that Short should appear at the same postcode during such a momentous time. Interestingly, Toplis headed directly to Monmouthshire before his breakneck escape to Scotland. The area had become something of a haven for deserters and there are 25 recorded cases of men working under false names on the sprawling forestry estate surrounding the Brecon Beacons (BBC, The Conscientious Objectors of South Wales in WWI). That Toplis landed a job on a forestry plantation in Scotland immediately after his trip to Wales, suggests a well established network may have greased his journey north. According to the Dundee Courier of May 7th, a cap with the rogue’s name in it was found in Pontypool, just 11 miles from Ebbw Vale. A week later there was another sighting. According to this report Toplis had been spotted in the mountainous, colliery village of Blaina, backing away from the police net put in place around Newport and Cardiff. A prayer meeting had been in progress at the Salem Baptist Chapel when a stranger wearing muffler wandered in. One member of the congregation describes Toplis sitting at the back of the church, wedged between two deacons. His head is bowed and his cap, wiped respectfully from his head as he entered the church, is twirled nervously between two fingers. He subsequently tells the worshippers that he has walked from London and is destitute. It would be an innocuous enough account if it wasn’t for two significant details. The Salem Baptist Chapel on High Street served the diocese of Blaina and Nantyglo. This put Toplis within just one mile of the village in which Mutineer Short had resided. Short was also a Baptist, so it’s not inconceivable that he and his family had sat among those same pews in the chapel. Just five years after Percy’s visit and only months after the Great Strike, the Blaina Cymric Miners Choir, composed entirely of unemployed miners, was to tour the Soviet Union where they staged a total of 60 concerts for mining and factory workers. Blaina and Nantyglo had endured some of the highest unemployment in the region and tensions in the community had been simmering for years. The depression here was as acute as it was prolonged. In response to the worsening conditions local leaders of the Communist Party of Great Britain had set up shop in the town, maintaining a stop-gap HQ on an old bus secured on large stone pillars. In the early 1930s with poverty now crippling the town, members of the Party, backed by the Bolshevik United Front and the National Unemployed Workers Movement took decisive action. The ‘Blaina Riots’, as they were known at the time, were the culmination of 20 desperate years of devastating means testing and benefit cuts. The people had decided enough was enough and a series of demonstrations was organised. One of the rallying points was that same Salem Baptist Chapel in Blaina in which Toplis had taken refuge. It was here that the demonstrators gathered. Unemployed miner and Communist Party member, Brinley Jenkins stood inside the chapel addressing the crowds, his stirring Welsh oratory energizing the mood and cranking up the volume no end. A total of 18 men were charged, 11 of them sentenced including Jenkins. All men were later released on the orders of the Home Secretary. Curiously enough, a deacon at the Chapel at the time of Percy’s visit was also called Jenkins. William Jenkins managed the local post office. Other deacons at the chapel like Caleb Lewis had been colliery workers. Was it possible that the two men called Jenkins were related? Toplis had spent a week in the area, with credible sightings at Pontnewynydd and Cwmffrwdoer all appearing in the national press.

When I was in The Kremlin in 1932 I was shown a map on which were marked potential revolutionary areas of the world. There were two red pins stuck in the British Isles – one in Clydeside and the other in the Rhondda Valley. But we in Monmouthshire always believed that the Eastern Valley was far more revolutionary than the Rhondda — Eddie Jones, Communist Party Councillor, Pontypool

In view of the resistance shown at the time of the Great Unrest, the region was more than capable of sheltering and supporting a scallywag anti-hero like Percy Toplis who would have had little or no conscience in exploiting their charity or ideals. And there was another thing; files recently released by the Freedom of Information Act reveal that between the years of 1931 and 1945 Hugh MacDiarmid, the area’s Scottish correspondent, had been placed on an Mi5 watchlist. The files describe him as a fanatic “only too ready to give his allegiance to any extremist cause.” (Security Reference /G/37b/63, National Archives). What exactly was he doing in Ebbw Vale at the time of the unrest? How had he procured his job at the paper? Immediately after being demobilized in 1919 MacDiarmid spent several months in the anarchist-artist haven of Marseille before returning to Scotland and co-founding the National Party of Scotland. During his time in Ebbw Vale he became a good friend of Keir Hardie. Welsh trade unionist, Vernon Hartshorn and Socialist politician, Victor Grayson were also known associates. Little more than 16 weeks after Toplis was gunned down in Penrith, Victor Grayson disappeared. No trace of him has been found since. Legend has it that Victor Grayson — suspected of spying for the Irish Republicans and the Soviets — was planning to dish the dirt on David Lloyd George, at this time British Prime Minister. At a public assembly event in Liverpool Grayson had claimed he had evidence that Lloyd George was selling peerages and was using Mi6 informer and theatre magnet, Maundy Gregory as bagman. Gregory was no stranger to blackmail himself, his Ambassadors Club in Soho used regularly to harvest gossip and supply leverage on prominent celebrities and politicians. By a bizarre stroke of luck, Grayson had marched into the Etaples Camp on the very day the Mutiny kicked-off. On a visit to Christchurch, New Zealand in November 1916 Grayson had enlisted in the 1st Battalion Canterbury Regiment – an Expeditionary Force who had first seen combat in Egypt in December 1914, before landing in Gallipoli the following year. Grayson arrived in France on September the 5th and on Sunday 9th of September they arrived at camp in Etaples. This was the day that attitudes at the camp had begun to seriously deteriorate. New Zealand Gunner A. J. Healy and several of his comrades had muscled their way through Police blockades set up to prevent privates entering Le Touquet. Healy was duly arrested and a mob had gathered at the bridge. Grayson had been on active service for little more than four days when he found himself at the eye of the storm. Shortly after order had begun to be restored on September 16th, Grayson, like so many of the soldiers involved, rejoined his battalion and was posted immediately to the front. On October 12th he was wounded in action and by March he was back in London. Grayson had been on active service for little more than 31 days and only a fraction of those in the field. To the best of my knowledge, not one of his biographers have explored his time in Etaples at the time of the famous riots (although the similarities between Grayson and Bleasdale’s, Monocled Mutineer character, Charles Strange, are remarkable to say the least).

As I stood amongst the shadows of the bothy looking out at the excitable daylight beyond the window, an idle fantasy was taking shape. Toplis was no stranger to Soho, but was he also no stranger to Grayson? According to the more lurid stories appearing in the press ‘post-mortem’ of his death, Percy had been an anarchist and leader of a ‘Free Love Club’ operating in the emigre communities of East London. Had Percy’s involvement in another sordid racket placed him in possession of damning material on high profile politicians that were going to be of unique value to Grayson? Had letters, papers and photographs fallen into hands that could somehow damage the reputation of senior government ministers? Did the ‘small parcel wrapped in brown paper’ about which Toplis had ‘displayed no small amount of concern’ contain a political bombshell? According to the hotel keeper in Inverness, Toplis claimed to have left the parcel at a nearby public house. Had this been part of an organised ‘dead drop’? Was he telegrammed this location? Coming back to Hugh MacDiarmid though, anything was possible and his proximity to Mi6 man Compton MacKenzie and the Highland Land League made his loyalties and commitments all the more problematic. In 1917 shortly after his recruitment into MI6, MacKenzie had become director of the Aegean Intelligence Service. Here they had recruited agents and personnel from forces stationed in Salonika. The creation of the AIS just happened to coincide with Toplis and MacDiarmid’s withdrawal from active service. And they had terminated that active service quite abruptly (and simultaneously) in Salonika of all places. Did orders from a higher chain of command account for Toplis’s ‘daring escape’ from the detention compound in Camiers some 12 months later? In his later autobiographical works, MacDiarmid confessed that the multilingual atmosphere of Salonika (housed as they were so closely with Serbian, French and Russian troops) had played a crucial formative role in his personal development as a Radical. Had it had much the same impact on Percy? Whatever the truth of the matter, MacDiarmid’s continued involvement in Scottish Nationalist propaganda, clandestine militarist projects and the literary Scottish Renaissance ensured his broad appeal to both radical and romantic alike and he remains a beguiling conundrum to this day.

Illegalists and Anarchists

Like Woodhall’s motor-gang nemesis Jules Bonnot before him, had Toplis, helped by radicals he’d met in the deserter camps around Camiers, somehow managed to embed himself into the deeply subversive sub-culture of London & Paris Bohemia? Did the freshly liberated women around Richmond and Chelsea present a lucrative new seam to mine? According to his 1929 book, Detective & Secret Service Days Woodhall’s earliest days in the Special Department were contemporary with the growing Suffragist agitation:

” I repeat that there was a considerable undercurrent of political bias in the movement, and if you had to examine the lists of Fascist women’s membership today, I think you would find a number of names that were there which were familiar in the days of the great Suffragette trouble.” — Detective and Secret Service Days, Edwin T. Woodhall, 1929

His Secret Service commander, Sir Basil Thomson shared much the same opinion, conflating everyone from Suffragettes and Irish Nationalists, Pacifists and British Marxists with the volatile political manqué supporting Germany’s ambitions. Interestingly, the street on which German Spy George Breeckhow took up residence in 1915 (Bloomsbury Street) became the HQ for the Left-wing and Suffrage periodical, Time and Tide. The hotel itself reclaimed its notoriety some 50 years later when British SiS agent, Frank Bossard (former member of the British Union of Fascists) was arrested at the Ivanhoe for spying for the Soviets. From Woodhall’s perspective Toplis must have seemed like Bonnot’s British counterpart. Both men were alleged to have been at the forefront of various ‘motor bandit gangs’, both had been trained in the ungentlemanly art of villainy in and around streets of Montmatre in Paris, both had found favour with anarchists and both had come into contact with the roaming Bolshevik contingent responsible for encouraging desertion in the woods and caves around Etaples (Bonnot’s mentor and colleague, Victor Serge was actually arrested in France with a small Bolshevik contingent in the period in which the Etaples Mutiny took place). Woodhall saw both men as vicious reprobates skilled at exploiting anarchy and extremism for their own mercenary pleasures. In a passage that looks like it might very well of come out a Brexit manifesto, Woodhall laments:

“The activities of Special Branch was formed primarily to watch the activities of certain undesirable visitors to these shores. The open door which it was Britain’s boast to keep for all, the asylum for which this country provided for the oppressed of other countries, and for refugees of all nationalities, was not without its very serious attendant dangers …. Frequently it was found that some of these alleged “oppressed” refugees were indeed, criminals of a very desperate order.” — Detective and Secret Service Days, Edwin T. Woodhall, 1929

Woodhall doesn’t mince his words when it comes to subversive movements, foreign or domestic. For the Toplis detective, any movement that condoned the use of illegal and anti-social methods to achieve objectives was destined to attract not just the ‘hysterical and fanatical element’ but also the criminal element. He said it was as true of the Suffragette Movement as it was the Irish Nationalists and the Communists. Criminal elements would ‘creep in and use the movement as tools to bring about their desired ends’. Latvian revolutionary Peter the Painter and French Anarchist anti-heroes like Jules Bonnot (both of whom make it into Woodhall’s book) are judged to be little more than lumps of iron pyrite masquerading as people’s gold, their extravagant ‘illegalist’ philosophies a rambling front for peasant envy. In Woodhall’s estimation Peter the Painter never organised a burglary or a robbery without emphasising to his comrades a ‘political angle’ to his schemes: anarchist last and criminal first. As Woodhall puts it, his anarchy was ‘used as a cloak’ to ensure the loyalty and commitment of a substantial political underground. Not that Woodhall wasn’t without some sympathy; ‘extreme poverty and conscious inferiority were always at the root of crime’, he writes. The deaths of Jules Bonnot and Peter the Painter in separate sieges in 1911 brought closure for the detective. Cases had been closed, crises had been averted and desserts, just or otherwise, had been emphatically served. Real or imagined, Toplis was a loose-end, his daring escape from the army’s detention compound on Woodhall’s watch wasn’t just an opportunity missed, but proof that subversion paid:

It is a well known axiom in criminal investigation, especially in political crime, that an unfinished crime is an automatic challenge to other fanatics! — Detective and Secret Service Days, Edwin T. Woodhall, 1929

The stake he finally drives though the heart of Bonnot and Peter the Painter may prove critical to our understanding of his narrative pursuit of Toplis. In a move that is clearly addressed to their legion of die-hard supporters, Woodhall makes a stunning ‘revelation’; Peter the Painter didn’t fight in the Siege at Sidney Street, but left his comrades to die, escaping to France in the hue and cry; he was a traitor and a coward. Woodwall’s pièce de résistance in the tale was even more shocking: Peter the Painter and Jules Bonnot were one and the same. He took exactly the same tack with Toplis: you couldn’t just a kill a man, you had to kill what he stands for. As John F Kennedy said, ‘a man may die and nations may rise and fall, but an idea lives on’. Woodhall would have to kill the idea. Anarchy though was one thing, espionage was quite another. In the relative calm of the ante bellum, subversion, though disruptive, produced little in the way of fall-out. Men would strike, they would go back to work. A fire would spring up, a fire would be put out. In war time Britain this was very different. Woodhall would be faced with a far greater concern than insubordination; had Toplis’s skills in impersonating officers brought him into contact with German or Communist spymasters? Bolshevik members of the rebellious First Russian Brigade had already played a central role in the French Army Mutinies in the Spring of that same year. The spark that had ignited the Russian Revolution was spreading throughout Europe and there was some indication that Germany were among those keenest to have Lenin and the Bolsheviks in power. Lenin hadn’t backed the war with Germany and there are those who believe the German government secretly provided safe-passage for the leader to return to Moscow from Switzerland in the Spring of 1917. As for himself, Woodhall claims to have helped foil an attempt by the The Russian Nihilist Movement in London to kidnap the young Russian Prince Alexei. He recounted similar stories of espionage and daring-do in his book, Spies of the Great War, published in 1935. Ever since encountering a young Lenin in London, Woodhall and Scotland Yard had been monitoring the emergence of Bolshevik networks in the Clydeside area of Glasgow. Woodhall had been tasked specifically with watching the ‘Russian Refugees’ in and around the Limehouse and Whitechapel. His encounter with both Lenin and Kropotkin on Jubilee Street is recalled in his 1936 book, ‘Secrets of Scotland Yard’. His feelings regarding the Russian Revolution of 1917 are unequivocal; “it was not a sudden and spontaneous, and unexpected event rising out of the extraordinary circumstances of the time” but the expression of a long, pent-up revolt. It was “the boiling point of countless schemes, which were conceived in misery and fostered in exile.” (Secrets of Scotland Yard, 1936). In January 1919 several Russian émigrés had helped foment a clash between 60,000 striking workers and Police and English troops. An estimated 10,000 English troops in total were deployed to contain the riots. This was in spite of a full battalion of Scottish personnel stationed at the nearby Maryhill barracks. Drawing on their considerable experience at Etaples, where Scots and New Zealand troops had been involved in the most violent skirmishes, law enforcers had made an educated guess that if a truly revolutionary situation was to develop then Scots soldiers were more than likely to side with the workers. There was intense speculation in Whitehall that foreign revolutionaries and foreign money were behind the strikes. Viscount Long, First Lord of the Admiralty, and Woodhall’s commanding officer at Special Branch and Scotland Yard, Basil Thomson, corresponded regularly on the issue. As far as Long was concerned, both the police strikes, the rail strikes and the strikes that broke out in the Clydeside area of Glasgow were the result of only one thing: “German Intrigue and German money”. In Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5, author Christopher Andrew suggests that privately Thomson may not have been entirely convinced that Long was right, but that he appeased him nonetheless. Thomson was well aware of wartime paranoia, drollfully observing in Queer People that it was ‘positively dangerous to be seen in conversation with a pigeon’ when hysteria was at its height. But there was something more pressing here; Long was a crucial ally in Thomson’s bid to fund and build the then nascent Mi5. Even if Long was being unduly suspicious, having these dark, elusive phantoms dominating the imagination of those in Whitehall was clearly desirable. Ghosts and enigmas like Percy Toplis were worth their weight in gold. In return for endorsing Long’s revolutionary conspiracies, Long backed Thomson’s request for a coordinated domestic intelligence system with a civilian as its head. The Battle of George Square as it became known was the culmination of years of hardcore activism. A series of local strikes and insurrections had followed an excitable flurry of anti-war demonstrations organized by Communist Celtic firebrand, John MacLean. In January 1918 MacLean had been elected to the chair of the Third All-Russian Congress of Soviets and a month later had been appointed Bolshevik consul in Scotland. He was even paid direct tribute by Lenin himself when the newly appointed Russian leader told his supporters that MacLean was one of the “best-known names of the isolated heroes who have taken upon themselves the arduous role of forerunners of the world revolution”. His outspoken opposition to the First World War, and his subsequent arrest under the Defence of the Realm Act made him a powerful national hero and an obvious enemy of the State. During the early 1900s, head of the Special Intelligence Service, William Melville (the original ‘M’) had spent no small amount of cash and resources infiltrating the Polish and Russian émigré communities, and many of these assets, like Percy, would not have been out of place among the more salubrious establishments of the European underworld. We need to remind ourselves of one thing here; although a skilled and resourceful player himself, there were those within the professional spying community who could seriously outplay Percy. Toplis Ace of Spies? I suppose anything was possible if you closed your eyes and fantasized long and hard enough. Had he been at any point a paid-informer? That certainly might account for his easy escape from detention (should it have ever really taken place). It might also account for how such a renowned deserter was able to re-enlist in the army in 1919. A total of 292 deserters had been captured and executed since hostilities began. Even during the peacetime year in which Percy re-enlisted a further six outstanding deserters were convicted and duly shot. The army themselves have no explanation for how Toplis was allowed to re-enlist. The logical explanation would be that he was never on a list of deserters and that his wartime deployment was at best rather fluid. On the otherhand, maybe the army simply couldn’t keep track of the sheer number of casual absconders leaking from battalions at this time. Percy’s itinerant life in Scotland during the 1911-1912 period could certainly have brought him into contact with Bolsheviks and anarchists, but there is no record of any political sentiments being expressed by the young rogue. The likeliest earliest encounter with these kinds of figures would have been during his two-year incarceration at Lincoln Prison, the correctional facility of choice for audacious Irish nationalists like Éamon de Valera and Conscientious Objectors like Fenner Brockway. Alternatively Toplis could very likely have fallen in with the French Milieu, a particularly vicious and well organized group of criminals operating in Paris at that time (Woodhall says Toplis was shielded by Parisian underworld after his escape from the compound at Le Touquet). British Intelligence began to see the Etaples riots as a deliberate plot by Bolshevik subversives acting on the orders of German agents to undermine the British and French war effort and started looking closer to home for possible clues.

The AG reported some disturbances had occurred at Etaples due to some men of new drafts with revolutionary ideas who had produced red flags and refused to obey orders. The ringleaders have been arrested and others sent to their units at the front — Douglas Haig: Diaries and Letters 1914-1918

Since the beginning of the war, the British Socialist Party (BSP) had packed a serious anti-war message; they’d also showed no small support for the Germans. After the war ended the BSP evolved into a more volatile revolutionary socialist organization, eventually merging with the Communist Party of Great Britain in August 1920. Active duty within trade unions and strikes became routine. The organization’s conference in Blackpool in 1913 attracted more than a 100 delegates. Lenin himself was aware of the event, worrying that the party’s newly emerging leader, Henry Mayers Hyndman, was increasingly supportive of British military intervention. And whilst this became something of a moot point among more radical members of the group, the BSP Annual Conference in Leeds at the time of the French Mutiny in April and the British-New Zealand riots at Etaples in September 1917, was all the proof that Cummings and the Security Service needed to suspect that British and French Pacifist organizations may have played a part. The idea that the military riots were spontaneous, and not communist in nature was rejected outright. Speculation and rumour can’t have been helped by the fact that the area in which some of the deserters were taking refuge was popular among Europe’s artists and intellectuals. Fabian Socialists like HG Wells and Amber Reeves had both eloped here. Back in Britain, the War Cabinet demanded a full assessment of the threat posed by anarchist and socialist movements, believing the groups to have been funded directly by German money. Between July and November 1917 a total of five British pacifist centres were raided, one of them at the Wakefield Work Centre in West Yorkshire (November 1917) and one at the Brotherhood Church in London (October 1917). This particular venue had been used by Lenin and the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party to host the group’s 5th Congress and was located on Southgate Road in the Limehouse district of London. Other Pacifist routs took place in Bristol, Manchester and Swansea. A committed Intelligence gathering operation had been in place since April and events in Etaples and La Courtine only ratched up concerns at the War Office that British subversives were accepting German money as a means of undermining the war effort. In September 1917, the month of the mutiny, Paul Bolo, editor of an anti-war newspaper based in France was arrested on his way back from Switzerland. He was believed to have been in receipt of German subsidies and was executed some twelve months later. Similar concerns were raised by Nicholas Klishko, a known Bolshevik with links to both the British pacifist movement and suspected German agents. If you found yourself under arrest as a Bolshevik in 1917, you were most likely suspected of being a German agent. Percy Toplis’ dramatic costume changes and his prodigious cash-flow shenanigans could only have aroused suspicion. If Toplis was impersonating officers and socializing with officers, then there was also every chance that he was privy to the secrets of officers too, making him an attractive and resourceful recruit to German agents. To the likes of Basil Thomson, Percy’s legendary promiscuity with women in the higher echelons of society followed the “usual spy routine of making love to impressionable young women and winning acquaintance by the promise of partnership” (Queer People, 1922). Much the same path had been followed by Carl Frederick Muller, an acquaintance of Breeckow and executed shortly before him in June 1915. Even if Toplis had been nothing more than a skilled and arrogant chancer it would be reason enough for someone like Woodhall to be suspicious. As head of counter-espionage in the Boulogne area and irrespective of any other crimes the ‘Military Ishmael’ may have committed, Toplis would have been on his radar. It also seems reasonable to assume that the military top-brass would much prefer passing off the mutinous incidents as the work of hostile forces – Bolsheviks, or otherwise. If it didn’t, the military would have some serious explaining to do. Recasting this impudent working-class villain as an accomplished spy and professional saboteur would certainly go down better with the Home Office. Explaining it as the result of a catalogue of military failures, including serial failures to either inspire or contain the troops, was likely to end several promising careers.