The scholar Thomas P. Riggio was among the first to explore the similarities between Theodore Dreiser’s Mr X in Twelve Men and Fitzgerald’s titular hero, Jay Gatsby, but few if any have explored Robin’s life in any real detail. This mini-book takes a look at the life and times of the sky-rocket millionaire from his days as a struggling immigrant bootblack in Times Square to his spectacular rise and fall of one of New York’s most flamboyant and mysterious millionaires.

The Ukrainian Gatsby

“I was impressed with this man; not because of his wealth but because of something about which suggested dreams, romance, a kind of sense or love of splendour and grandeur which one does not encounter among the really wealthy. He seemed to live among great things …” [1]

And so it begins. With just a few strokes of his pen, the 48 year-old veteran author, Theodore Dreiser, thrashes out the first rudimentary sketches of what might eventually turn into F. Scott Fitzgerald’s hero, Jay Gatsby, the fabulously cool yet just as fabulously fake millionaire bootlegger who now stands like some colossus at the golden gates of the American Dream: the International Man of Mystery, now, then, tomorrow, perhaps forever. In Collodi’s classic children’s story, Pinocchio starts off as a common, log-wood puppet before completing the moral assignments that turn him into a ‘real boy’. In a reversal of Collodi’s story, the exquisitely turned-out bootlegger that comes to life under the pen of F. Scott Fitzgerald, evolves, at least in part, from the real man. Fitzgerald would later describe Gatsby as an ‘amalgam’. He had taken people he had known and blended them with his own self-idea. In the end, the real man (or real men to be fair) is hewn to fairy-tale perfection in one of the most beautiful and most successful literary extrapolations by one of Dreiser’s most devoted fans.

Not that Dreiser would have been aware of any of it. The man who suggested “dreams, romance” and other “great things” wasn’t known as Jay Gatsby at this time but as Mr X, an anonymous yet beautifully realised character in his 1919 book, Twelve Men, a collection of twelve biographical sketches of men that Dreiser had known during his time as journalist and newspaper editor, men who had, to one degree or another, influenced his life or his writing in some way. None of the men in his book are well known. In fact all of them are rather obscure. One of the men is the Dreiser’s brother — the songwriter Paul Dresser —whilst other figures include Mike Burke, a foreman at the New York Central Railway, Harris Merton Lyon, a writer he knew at Broadway Magazine, William Muldoon, a former Wrestling Champion who had helped Dreiser back to health after suffering a nervous breakdown and Thomas P. Taylor, a former mayor.

The book had been roughly divided into six men who had triumphed, and six men who had, with varying degrees of defective heroism, failed in some way. Mr X was man number nine, one of those who had failed. His real name was Joseph G. Robin the ‘skyrocket financier’ from Long Island, New York who had been convicted for grand larceny in 1911, and whose spectacular rise within the upper echelons of Manhattan’s financial district had only ever been matched by his just as spectacular fall. His was a story of boom and bust, of dreams and ambition pushed just that little too far. And the soundtrack to that story wasn’t the roaring thunderclap of Casey Jones’ engine steamin’ and a rollin’ at the throttle of the Cannonball Express, it was the sound of the boosters peeling prematurely away from the rocket and falling noisily back down to earth. Robin’s crime, or so it was alleged, had been the misappropriation of some £90,000 in funds whilst serving as President of the Washington Savings Bank. He’d been shuffling the assets around in the most creative and lawless of fashions, setting in motion a sequence of disasters that destroyed several organisations and brought down several powerful figures. A high-profile court case ensued and the ‘bootblack who made a million from Niagara Falls’ found himself facing a lengthy spell in jail. For Dreiser, Robin and his story defined the period perfectly, a period when the financial mechanisms of America were at their most extravagant — when no gesture was too grandiose and no risk was too great. He wasn’t of noble birth, but that certainly didn’t stop him trying to pass for a man who was: “He looks like a Russian Grand Duke. He has the manners and tastes of a Medici or a Borgia. He is building a great house down on Long Island that once it is done will have cost him five or six hundred thousand.” [2]

Born Joseph Gregory Rabinovitch in Odessa, Ukraine in 1877, Joseph G. Robin had been one of the many thousands of penniless Russian immigrants flooding into North America in the wake of the Tsarist pogroms. Within twenty-years he had become one of the wealthiest and most successful bankers on Wall Street. Dreiser had first encountered him in 1907 when he was editor of a successful New Woman’s journal and on his regular trawl of the parties for the ‘imitate revelations’ and much-sought confidences of the gossiping Smart Setters which provided the basic fodder of stories for the magazine. And it was at one of those parties that he had first met Robin.

By this point in time, the man who had once been so poor that he had tramped the streets of the Lower East Side of New York up to his knees in snow, shoes collapsing around his feet with no more than a shirt on his back, now controlled four banks, several trust companies, a hydro power company, a railroad company, an insurance company and a series of real estate ventures. In Dreiser’s estimation, Robin was showy, he was gaudy and had the “flare, recklessness and imagination” that gave him the sparkle that those who were born into money could seldom match. [3] For those who have watched either of the movie versions of The Great Gatsby, or read the novel, there’s a feeling of familiarity in the scene that Dreiser paints of the meeting. On his arrival at Robin’s party, Dreiser, rather like Gatsby’s gentle and reflective narrator, Nick Carraway, is greeted by a rare and exotic human menagerie: opera singers, an Italian sorceress, a bevy of stage beauties, singers, writers, artists, poets. There is a parallel scene in Gatsby in which Daisy, blown away by the size of his new house, asks Jay how he could possibly live there alone. Jay replies that he keeps it always “full of interesting people, night and day — people who do interesting things. Celebrated people”. Robin’s mansion was just the same. His host, who he describes as somewhat “savage and sybaritic” in nature, had surrounded himself with a wild and eclectic coterie of supporters and hangers-on. The Pharaoh of Long Island was weaving dreams of grandeur “so outré and so splendid that only the tyrant of an obedient empire, with all the resources of an enslaved and obedient people could indulge with safety”. [4] Dreiser shares with the narrator of Gatsby not only the same giddy fascination with his host, but the same niggling sense of revulsion too. His host is a master magician and has created the whole absorbing spectacle for his own amusement. Yes there was something “amazingly warm and exotic” about Robin, but there was also “something so cold and calculated.” [5] The host regarded, and retained his guests with the appetite and curiosity of a collector. They were his butterflies, his “specimens”, each with their own unique charms and properties. Unlike Gatsby, women didn’t hold quite the same fascination with the author describing them as the “fringe and embroidery of his success and power”. He was the ruler, the “cangrande”. In spite of this, Dreiser liked him.

Like Gatsby, Robin is described as a shy beast socially, and it is not until later in the evening that the master of the house makes his entrance. When he does he is not the gorgeously blonde Adonis made famous by Robert Redford but a stockily built man, a little taller than average in height, with “curly black hair, keen black eyes, heavy, overhanging eyebrows, full red lips and a marked chin ornamented by a goatee.” Dreiser reflects that he is like a “Pan” figure, someone as oblivious to the formalities of social life as a goat is to dining etiquette. [6] For the author, there is something raw and elemental about Robin, a disruptive ‘pagan’ energy that seeks to jam the circuitry of predictable life. Here was a man who saw the sun go up and the sun go down, the wind blow to the east, the wind blow to the west, the tides move forward and the tides roll back and yet as happy as he was to observe these pleasingly familiar phases had never been completely satisfied with such a dull and automated cycle. It was all boring, all old news.

Ecclesiastes 1:2-11: ‘Vanity, vanity, says the Preacher’. Dreiser used the phrase for his chapter on Robin. There was nothing new under the sun. What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done. America was locked in an interminable loop and it couldn’t break free of its orbit. The laws of precession had taken over. The word used in the original Hebrew text of Ecclesiastes was ‘hebel’ meaning ‘vapour’ or ‘mist’. It alludes to the ultimate emptiness of all ‘vanity’ — the inevitable return to ashes. The only man in New York who seemed to want to change this was Robin. Robin wanted a world that was shiny, bright and new — and he wanted it all of the time. He wanted to see new things, hear new sounds, drive at new speeds. He wanted to go beyond ‘terrestrial consciousness’, ‘beyond the wall of sleep’— boldly or otherwise. [7] Robin even has his own personal advisor, De Shay who provides counsel in all matters of ‘social progress’, keeping him regularly updated on new music, new literature, new people, new pleasures. This first encounter with Robin, who Fitzgerald never met as far as we can determine, sets in motion a remarkable creative synthesis that begins in the warm, moist air of life before condensing into the miraculous fine spray of fiction and from there — into the mists of legend.

Icarus Falls

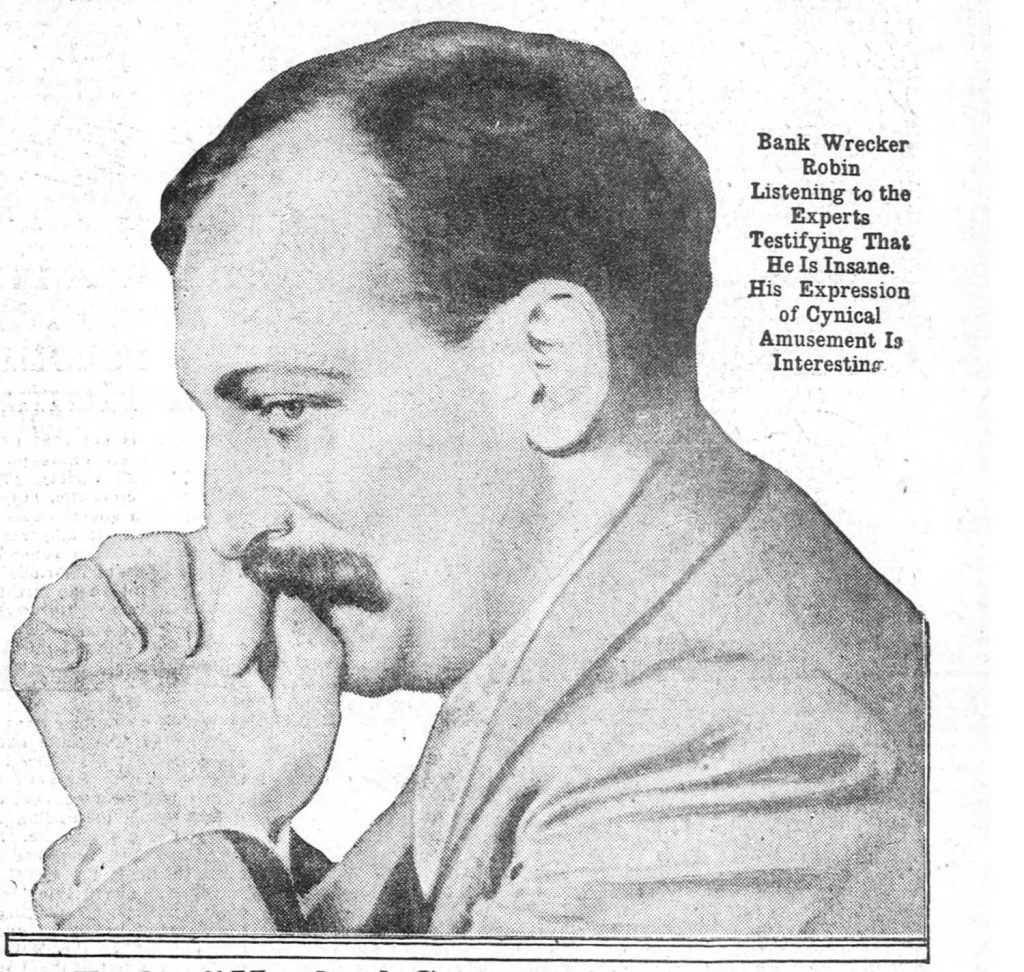

Just as stars rise in the night sky and sparkle, there has to come a time when they fall and fade also. Dreiser had so far only told half of the story, the story in which a talented entrepreneur from the Lower East Side had transformed himself into the ‘cangrande’ of New York having made the miraculous transition from bootblack to bank-owner in little more than a decade. The change that would destroy Robin would come during the fall of 1910 when out of a clear blue sky, the sky-rocket financier had found himself thrust into the media spotlight. According to the newspapers, several of Robin’s banks and business projects had been at the centre of a crude and unsuccessful attempt by the United Copper Company to the drive up the price of copper in 1907. This attempt had led to a chain of disastrous of failures, as the banks and trust companies who had poured money into the scheme started falling one by one. Within a week, the city’s third-largest trust, The Knickerbocker Trust was near to collapse. The role played by Robin in the so-called ‘panic’ had come to light during a five year investigation into the head of the United Copper Company, F. Augustus Heinze of 42 Broadway. [8] A report in the New York on May 11, 1910 described how Heinze, a partner of Robin in his ‘Bank of Discount’, had, at Robin’s request, deposited £400,000 in cash and securities into another of his banks, The Riverside Bank, in an effort to keep it afloat. The incident dated back to the ‘Knickerbocker’ panic of October 1907. In return, Robin’s bank had promised to hold all of Heinze’s securities then and previously deposited until the panic had subsided and Heinze was in a better position to redeem them. [9] The same thing was being repeated at several other banks and trusts in Robin’s care. Robin, Heinze and several other associates of theirs had been juggling around assets and buying up cheap shares — a common enough practice among banking officials and stockbrokers but on a scale that made previous attempts to control the markets seem fairly crude and fairly pedestrian. He was a genius with figures but the whole had been a gamble, and the vast majority of the people who lost were the ordinary working men and women of New York. The money that Robin was gambling with was not his own. Despite the commonality of these practices in the banking system the press were all over him; his career as Trimalchio was over. [10] Dreiser writes of his shock at the transformation in the second half of his portrait: “although no derogatory mention had previously been made of him, the articles and editorials were now most vituperative. Their venom was especially noticeable. He was a get-rich quick villain of the vilest stripe.” [11] There was something else that Dreiser had noticed too. The decision to launch a separate prosecution against Robin had come at a time when he had begun to make serious inroads into the Long Island Street Railway market, putting him directly up against rival Tammany figurehead, August Belmont Jnr. who in December 1905 had sensationally bought-out Thomas Fortune Ryan of the Metropolitan Street Railway Company. For the best part of seventy-years the Tammany Hall had been the power house of the US Democrats — the seat of concentrated power in New York, and concentrated, more often than not, in just one man.

During its golden era it was hard-boiled men like William ‘Boss’ Tweed and Richard Croker, who had earned their reputations through ‘graft’ and illegal means, but by the early 1900s the power was being more evenly distributed among its wealthier, more respectable and aristocratic patrons like Belmont and new ‘Boss’ Charles F. Murphy. It was a well-oiled and particularly well organised ‘machine’, brutally maintained and staffed by well organized crime. Like any machine it had its power-source, the immigrant vote, and its sensors and controllers. For Tammany Hall, the sensors and controllers were the street gangs of New York, first the Bowery Boys and then much later crime bosses like Arnold Rothstein — the ‘Meyer Wolfshiem’ of the Gatsby novel. It was a powerhouse marriage that gave them control of the police, the courts, the juries, the racecourse, the ring, the ballpark and all of New York’s major industries. The Metropolitan Railway buy-out placed Belmont at the head of the city’s traction industry. As a result, shares in his business had rocketed violently. A rival line would send them tumbling. [12] According to the press, Long Island was one of Metropolitan’s ‘clover patches’ and Robin’s overnight success in the industry was making the newcomer unwelcome. His South Shore Traction Company, which had just opened a 56 mile long trolley route from Babylon and Amityville on the South Shore of the Island to Manhattan via Queensboro Bridge had infringed on territory under the tight control of Tammany Hall. [13] The first section of the line had just been completed that summer with the cost of a fare significantly lower than average. In the fall, a close examination of transactions in the company books unearthed several queer practices within the trusts holding the traction company’s bonds and Robin’s dream of revolutionizing the passenger and freight business of Long Island started to crumble. [14]

Ten years earlier Robin had played a key role in a bid to keep Tammany veterans Nicholas Muller and Perry Belmont — August Belmont’s brother — out of Congress in an era defining battle for New York’s Seventh District. [15] In his efforts to show the considerable influence being brought to bear on Robin, Dreiser quoted a report from a New York newspaper in which it was being alleged that a ‘hitch’ in a deal which was to have transferred ownership of Robin’s South Shore Traction company to the Long Island Electric Railway, controlled in part by August Belmont and the Interborough Rapid Transit Company. The deal would have seen Robin make some $2 million in profit. The deal was said to have been blocked by powerful figures on Wall Street and the clearing house refused to clear the necessary funds for his banks. ‘Sinister influences’ were said to have blocked the transfer and frozen had further opportunities to act. [16] A petition of bankruptcy had been filed against Robin’s Realty and Security Company in Broadway which had been handling the deal. It was alleged that the company was insolvent and no longer in any position to make the necessary transfers. Robin now faced charges of juggling the accounts of the various banks and trusts he owned, transferring, temporarily, the funds of one bank to another. Large sums of money would be drawn out and put down as securities on new companies and new ventures he was organizing. As Dreiser was quick to point out, these “tricks” were the standard practices of Wall Street: he had been taking money from Peter to pay Paul, “washing one hand with the other,” as they said at the time. According to Dreiser, Robin would tell the grand jury that he had received a direct warning from August Belmont Jnr. not to get involved in the deal: “Listen closely to what I am going to say”, Belmont was speaking quietly, “I want you to get out of the street railway business in New York or something is going to happen to you. I am giving you a reasonable warning. Take it.” [17] Within days a formal investigation into Robin’s traction dealings had been launched and a Federal receiver appointed to liaise with the company’s treasurer Frederick K. Morris and its Vice President, William L. Brower. It eventually transpired that the books at the traction company were on the level. Unfortunately for Robin, the investigation into his books had expanded to into the various checks and the balances of his other banks and trusts and discrepancies were found at three of them: the Aetna Indemnity Company, the Northern Bank and the Washington Savings Bank. James M. Gifford, Robin’s co-director and attorney his Northern Bank, tried to dodge the investigation: he had never been connected with any of the acts of wrong doing as Robin had employed outside counsel on all matters relating to the fraud. Few seemed to pick up on the fact that Gifford had previously been counsel for the Hamilton Bank in 1906 and had found himself in much the same position during the panic of 1907, when a similar trail of discrepancies had brought it to the attention of the courts. A short time later the bank’s director and chief cashier, Jesse C. Joy had shot himself dead at a New York sanatorium where he had been checked in as a patient. Joy is alleged to have been frustrated by the methods used the bank’s director, the United Copper magnate, F. Augustus Heinze, Robin’s partner at the ‘Bank of Discount’. [18] As a result of the Hamilton scandal Heinze resigned and the bank changed its name to the Northern Bank. Gifford was retained as counsel and Robin, now one of the trustees of the Carnegie Trust Company, had been brought in as director. Resigning from their positions were ‘ice king’, Charles W. Morse, a close associate of former Tammany Boss, Richard Croker. Morse had also featured in Robin’s acquisition of the of the Riverside Bank. As usual, the deal would be made through Morse and once closed Robin would throw out the old officers and replace them with men of his own choosing. [19]

Another of the men who would submit their resignation over the Carnegie Trust affair was Edward Russell Thomas, a businessman, publisher, Broadway mogul, horse-breeder and race car driver who had been born into one of New York’s ‘Old Money’ families. Racing his Daimler Phoenix ‘White Ghost’ at over 40 mph in West Harlem in Upper Manhattan, a district popular with powerful men driving powerful cars, Thomas mowed down 7-year-old Henry Theiss who had been out with playing with friends. The boy died instantly upon impact. Thomas would repeat much the same offence with the same car in January 1904 in Gaeta near Naples when he killed a young peasant woman in a cowardly hit and run which saw the playboy millionaire raced-off with his beautiful actress girlfriend, Theodora Gerard at great speed to Paris. [20] Even in spite of the accidents, Thomas remained a key establishment figure at the Union Club — a more fashionable, cross-party rival to the more conservative and ‘aristocratic’ Knickerbocker Club.

As the son of Union Army General, Samuel Russell Thomas, Edward may well have been an associate of Robin’s business mentor, General James R. O’ Beirne, the former Provost Marshall of Washington D. C. and another gallant ‘Union’ man of the Civil War era. If the Gatsby novel was the story of beautiful yet “careless people” who “smashed things up” then retreated back into their fabulous wealth and “vast carelessness” unscathed, there were few more careless than the Thomas-Heinze clique that acted as Robin’s rocket boosters. [21]

The Hamilton Bank formally reopened on January 2, 1908 with Robin in charge of a syndicate managing its renewed interests. Dreiser explains that anyone who has read Frenzied Finance by Thomas W. Lawson and Lawless Wealth by Charles E. Russell would understand the cutthroat rivalries existing between ‘new money’ Trimalchios like Heinze and old banking conservatives like John Pierpont Morgan. One thing seems clear: the Northern Bank had been up to mischief well before Robin had come on the scene, but it had little bearing on the investigation carried by the Justice Department into Robin in 1911.

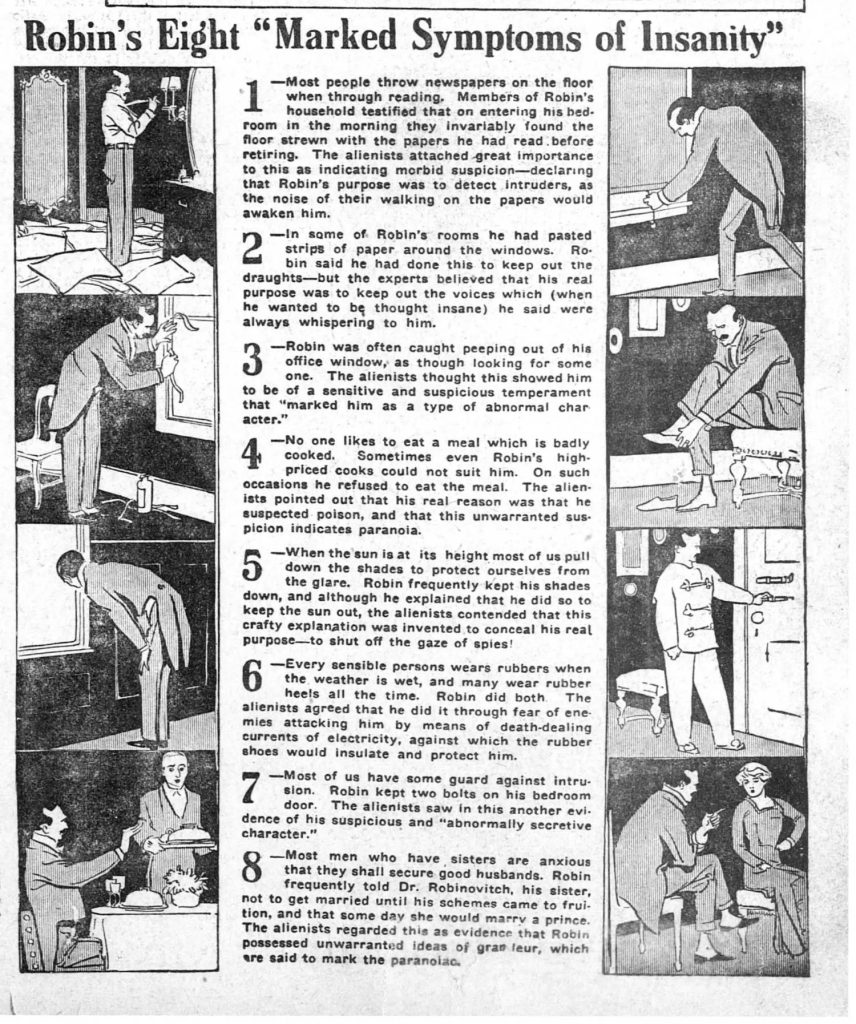

As far as Robin was concerned it was his foray into August Belmont’s traction industry that had made him such a threat. As soon as Belmont had issued his threats the interest of the interest shown by New York investors went cold. The depositors had withdrawn, the securities had bombed, and fear of ‘trial by association’ had seen each desert Robin, one by one. Nothing was so “squeamish or so retiring as money”, he once mused. [22] This instant retraction of friends is repeated in the Gatsby novel. Gatsby has just been murdered by Wilson and the papers are crackling with rumours about his life. Nick, the book’s narrator and a man that Gatsby has known only for the duration of that summer, is left to arrange the funeral but nobody wants to know — not Daisy, his former sweetheart, not Meyer Wolfshiem his mentor, not any of the hundreds of ‘friends’ who had attended his lavish, life-affirming parties. Everybody was suddenly unavailable. Nobody was interested in Gatsby anymore. Dreiser observed much the same thing with Robin: “I never saw such a running to cover of friends’ in all my life”. As the lurid stories about Robins parties and his lifestyle gathered pace in the press, all those who had attended his parties and ridden in his cars suddenly knew absolutely nothing about him. Even his closest friend and aide, de Shay, had deserted him. In interviews with the press de Shay would express his shock at the man who had robbed millions from the poorest of people. According to de Shay he had been tricked into attending the parties. None of it was true, of course. As Dreiser explains in his portrait in Twelve Men, there wasn’t the slightest evidence that Robin had robbed anyone. The money he had been juggling from one bank to another had been his own.

Slaying Dragons

The man brought in to defend Robin at his trial was the indomitable ‘courtroom warrior’ William Travers Jerome, the tirelessly energetic former District Attorney of New York. Jerome was an unsmiling broad-faced man of fifty whose neat and very solemnly-trimmed moustache and pince-nez gave him the look of a bible thumping Baptist minister. He’d been twelve months out of the job as District Attorney, having lost the battle to Republican, Charles S. Whitman the previous year. Jerome was the man who had spearheaded the decade long fight against political corruption and organised crime that had gripped the city when the “thick-set and scrubby bearded” Irish-American, Richard Croker replaced ‘Honest’ John Kelly as Grand Sachem of Tammany Hall in the final years of the 19th Century. [23] Writing in his 1931 biography of Croker, the controversial author and historian Lothrop Stoddard had described how Jerome had a knack for dramatizing the sordid tragedies of commercialized vice — the majority of whom were the daughters of immigrants on the Lower East Side: “Foreign-born audiences on the East Side, who could scarcely understand English, sensed his meaning and burned with indignation. Bearded Jews, and swart Italians, fathers of growing daughters, sobbed and wailed as they listened to Jerome”. Stoddard’s assessed that it had been little more than a ploy to steal votes from the Democrats to Jerome’s newly revived Reformists. [24]

To his friends and admirers Jerome was the Saint George of Manhattan, slaying dragons of the underworld renowned for his “ruthless examinations and incisive summations”. [25] Chicago had Elliott Ness, Gotham had Batman, and Lower Manhattan had William T. Jerome. According to Lothrop Stoddard’s much quoted book on the Croker era, Master of Manhattan, the Jerome family had allied themselves, as “good democrats”, with Boss Tweed, the Boss-man of Tammany Hall during the Hall’s no less scandalous ‘golden period’ in the late 1860s and early 1870s. When Croker had finally been disposed of in 1902, it was felt that Jerome had lost his edge, and fallen back in with the more righteous Tammany crowd under its new Boss, Charles F. Murphy and his more respectable, middle-class patron, Thomas Fortune Ryan — the man who had been forced to concede ownership of the Metropolitan Street Railway Company to Robin’s nemesis, August Belmont Jnr just five years before. It had been Murphy who had backed Jerome for the District job in 1902 and again in 1905, although he was keen to emphasise the fact that he had no love for him personally. [26] At the beginning of his career he had been passionate about social reform, protecting the poor from the careless excesses of excessive wealth. Now his attention had turned to protecting the excesses of wealth from the trust-busting, anti-Capitalist heroics of President Theodore Roosevelt whose efforts to curb the reckless, insatiable appetites of unrestricted trade brought him into conflict with the biggest wolves on Wall Street, J. Pierpont Morgan and Thomas Fortune Ryan. The sources of all America’s woes were no longer the corrupt politicians and police officers but the unregulated practices of corrupt bankers. There was chaos were there should be order, darkness where there should be light. The most dangerous of all classes, Roosevelt had concluded, were now the wealthy criminal classes. As far as the President was concerned, Jerome had grown lax in his prosecutions as friends and family grew wealthy off the back of a new and cleaner Tammany machine. Before long, rumours started to spread that Jerome had been quietly stonewalling efforts to explore the crooked affairs of Ryan’s Metropolitan Street Railway and the executives who had been looting its handsome coffers.

When President Roosevelt heard the rumours that Jerome had been seen dining, shaking dice and sharing drinks with suspects Ryan and accident-prone playboy, Edward Russell Thomas — a member of Robin’s Hamilton-Northern Bank clique — his career as Sir Galahad came to a less than chivalrous conclusion. Providing legal counsel to Thomas when he was due to be indicted in the banking cases of 1907 had been the final straw. [27]A Grand Jury was convened to investigate his dereliction of duty. According to Judge Samuel Seabury, who had been called a witness, the New York District Attorney had failed to make an “honest effort to prosecute wrongdoers” in connection with jury-fixing matters connected to the investigation of the Metropolitan Street Railway.” [28] Jerome had lost his dignity. [29] But it hadn’t always been like this. Far from it.

read on …

[1] Twelve Men, Theodore Dreiser, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998, pp. 264-265.

[2] Twelve Men, Theodore Dreiser, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998, p.271

[3] Ibid, pp. 264-265.

[4] Twelve Men, Theodore Dreiser, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998, p. 270

[5] Ibid, p. 271

[6] Ibid, p. 267

[7] Beyond the Wall of Sleep is a collection of short stories by American author, H. P. Lovecraft, published in 1943. One of the stories, The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, features a groupof Pan-likealien creatures what might be the original source of the Star Trek mission statement: ‘To boldly go where no man has gone before.’

[8] 42 Broadway would later be used as an address by ‘Bootlegger Gatsby’ Max von Gerlach, an associate of F. Scott Fitzgerald, who is believed to have provided Gatsby with his famous ‘Old Sport’ salutation. Heinze, one of the Copper Kings of Montana, had been born in Brooklyn to a German father and Irish mother. In 1869

[9] ‘Defense Puts Value on Heize Coppers’, New York Times, May 11, 1910, p.6

[10] TGG, Penguin, p.108.

[11] Twelve Men, p.276

[12] ‘Belmont is Traction King’, New York Tribune, December 23, 1905, p.1

[13] Queensboro Bridge is the bridge used by Nick and Gatsby during their breakneck dash to New York in Gatsby’s Yellow car. Gatsby is recognised by the Policeman who stops him for speeding and then let’s him off. It was an area controlled by the Tammany Hall and its gangs.

[14] ‘New Trolley Road Opened at Babylon,’ New York Times, June 12, 1920; The Western Underwriter 1910-12-29: Vol. 14 Issue 52, 29 December, 1910, p.27

[15] The Seventh District comprises areas of Lower Manhattan, Queens and Brooklyn — the immigrant engine-rooms of New York.

[16] Twelve Men, p.277

[17] Ibid, p.283

[18] ‘J.C. Joy Takes His Life’, New York Tribune, December 1, 1908, p.7; ‘Says Hamilton Bank Made Usury Charges’, New York Times, December 10, 1907, p3. The press of the period use the phrase, the E.R Thomas-Heinze’ clique, a reference to Heinz and his partner Edward Russell Thomas,

[19] ‘Millions from Nothing’ Alaska Citizen, February 13, 1911, p.7

[20] ‘Broker’s Ride Kills Boy’, New York Tribune, February 13, 1902, p.2; ‘Rich New Yorker’s Auto Kills Woman in Italy’, Washington Times, January 9, 1904, p.3. The car had been owned previously by a member of the Vanderbilt family.

[21] TGG, p. 170

[22] Twelve Men, p. 284

[23] Master of Manhattan, Lothrop Stoddard, Longman Green & Co, 1931, p.241

[24] ibid, p.249

[25] Courtroom Warrior, Richard O’ Connor, Little Brown and Company, 1963, p.5

[26] ‘Murphy Wished Jerome on Ticket’, New York Times, February 6, 1906, p.16

[27] ‘New Yorkers Try to Oust Jerome’, The Irish Standard, May 30, 1908, p.7; ‘Thomas Wants Court to Throw Out Indictments’, The New York Evening World, June 25, 1908, p.8

[28] ‘The Hearing on the Jerome Charges’, The Bellman, Volume 4, p.659

[29] Courtroom Warrior, Richard O’ Connor, Little Brown and Company, 1963, p.5