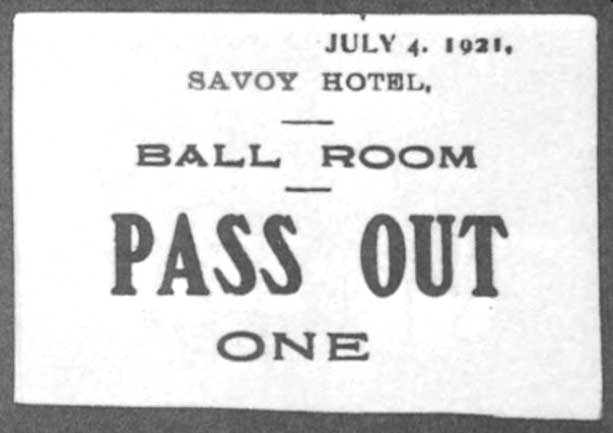

The ending of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining has chilled and intrigued movie-goers for years. In the closing scene of the film the camera moves from Jack Nicholson’s Jack Torrance sitting upright, dead in the snow, to a gallery of pictures in the ballroom of the Overlook Hotel. On one of the pictures is Jack in a black Tuxedo. The date and location of the picture are written in script at the bottom: Overlook Hotel, July 4th Ball, 1921. What did Kubrick mean? Is it a simple case of reincarnation or are there hidden dimensions that throw light on American history and the troubling dark-side of the American Dream?

July 4th 1921, The Cecil Hotel

Recently I’ve been taking a look at F. Scott Fitzgerald’s trip to London in the summer of 1921. That journey ended with a Fourth of July celebration at the Hotel Cecil. Making speeches there that day was George Harvey, President Warren G. Harding’s new Ambassador to Britain and one of several US dignitaries who had sailed with Scott to Britain on the RMS Aquitania in the first week of May. On March 4, Harding’s predecessor, President Wilson, the man who had drafted his own idealist and uncompromising vision of America’s future with The League of Nations, descended from the White House portico and drove away to become “plain old Woodrow Wilson”, a man whose failing physical and mental condition now mirrored that of his cherished League. As Scott Fitzgerald and Ambassador Harvey steamed across the Atlantic in May, they were sharing the decks with Colonel Edward M. House and Henry White, the men who had very generously and very loyally supported President Wilson in drafting his plan for the League.

At the celebration dinner at the Cecil that night, Harvey had addressed the various misconceptions about America’s newly elected President and the wild, wild rumours that American wealth, its ‘happiness and its opulence’ were a direct result of the war. There was a myth taking shape in Europe that unlike other allied nations, America was now rich “beyond the traditional dreams of avarice.” America and Britain were at a crossroads: should America preserve that ’special relationship’ and move even closer to the British Empire or should they start thinking about an ‘amicable’ separation? Harvey, the ‘Green Mountain Boy’ of Vermont was there to reveal a subtle shift in the country’s axis. America, the ‘shining beacon of hope in the world’, was preparing to dazzle a little less generously than before. At his inaugural address in March, Harding had revealed an America that in the “clarified atmosphere” of the post-war period was demanding a change in national policy. ‘Internationality‘ had begun to “supersede nationality”. It was Harding’s belief that “materially and spiritually” the success of the Republic had always been in the wisdom of the “inherited policy of non-involvement in World Affairs”. Woodrow Wilson’s lofty pursuit of lasting world peace with a League of Nations was viewed by many as the actions of a vain, delusional man whose obsessive quest for glory had been nothing short of madness. The President’s incorruptible dream was not only jeopardising the country’s independence, it was ‘destroying the soul’ of ‘this great Republic’. To the many Americans who clung on to the ideals of freedom and independence, nationality was not a pariah but a panacea — a vital force, a prayer, a guiding light. After the extravagant ideals of the Wilson Administration, the White House would be inducing a cold, hard freeze that would wake them from their crippling ‘Potomac fever’. Wilson’s Narcissism was out. Harding’s Echoism was in. The headlines in American newspapers the day after his inauguration spelled it out: ‘No Alliance with Old World, Promises Harding.’

At a keynote address in Chicago in June 1916, Harding had left the audience in absolutely no doubt, right from the start, about his intentions in the years ahead: ‘American opportunity for American Genius, American Defense for American soil’. The ‘America First’ slogan he had been shouting for the past five years would set the conditions at home ‘for the highest human attainment’. In March 1920 Harding had addressed a meeting of the Winter Night Club held at the Antlers Hotel in Colorado Springs. Joining him was Boulder man, George Irey who was handling his campaign locally. The issue under discussion that night was Mexico. America’s part in the Great War had been “primarily and patriotically” in defence of its national rights, something he had no trouble getting behind. As far as Harding was concerned, “a nation which did not protect its citizens did not deserve to survive.” Politically, the State of Colorado was split between the heavily populated Mexican-American south-central region and the Klan dominated Methodist ‘bible belt’ running from Larimer County north to the High Plains. Harding might not have said he wanted to build a wall that night, but his nativist instincts told him that the hole in the border began right here.

His address to the Winter Night Club that night couldn’t have been better timed. After twelve years as a solid Democrat base, Colorado was taking the kind of swing to the right that would sweep Richard Nixon to victory almost half a century later. Once he had the keys to the White House the changes he was anxious to make moved along at a rattling pace. Although the Alien Restriction Bill passed in spring 1921, didn’t impose the same numerical quotas or restrictions on naturalization as it did on migrants from south eastern Europe, it did mark a period in which the light of Lady Liberty was dimmed a little. For a time at least, America’s intuitive grasp of progress was being put on hold. The next two scandal-prone years would see Harding and his supporters demanding an extended drying-out period of reflection and isolation: Americanism would ‘start at home and radiate abroad’. It was like America was trading in the comforts and conveniences of the Melting Pot metropolis for the shivering polar exile of a Rocky Mountain winter. The solitude they would endure would either twist and damage ‘American Genius’ forever or transform their glorious dreams and ideals into ‘glad realities’. One ‘great storm’ had passed but America was preparing for another one moving in. [1] Although staying at the Cecil for the duration of his stay in London, Scott didn’t make the dinner on the ‘Glorious Fourth’. A ‘gloom’ was hanging over it like a cloud. Instead he and Zelda headed over to The Savoy Hotel Grill for dancing and champagne. The six-piece band, Sherbo’s Orchestra, led by the jazz-loathing Dullio Sherbo, had just arrived from New York and The Frolics were in from Paris.

July 4th 1921, The Overlook Hotel

It was on Independence Day 1921, in another time and another dimension, that Jack Torrance, took up his creepily implausible place in a photo showing the 4th of July celebrations at The Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. In the story, Jack is a struggling writer who has taken the job of off-season caretaker at a decadently grand and historic hotel in the remote Colorado Rockies. Falling further and further into his alcoholism and psychosis, Jack runs amok with an axe, hunting down his family like prey. The 1979 film starring Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall has many disturbing moments, but it’s the picture that chills the blood and lingers in your mind long after the film has finished. The shot begins with Jack’s death in the snow of the hotel maze in modern day America, and concludes with the camera zooming slowly on a gallery of photographs in the hotel’s ‘Gold Room’. [2] The eighteen pictures that make up the gallery are all black and white and all the people in them are dressed in familiar period clothes. As the Steadicam camera advances slowly toward the gallery, we hear the sweet, melancholy refrains of Midnight The Stars and You by Ray Noble and his Orchestra. Just six years earlier, the haunting period tones of Noble’s lavish big-band sound been had channelled as part of the soundtrack to Jack Clayton’s Gatsby. As the music plays, the camera hones in on a small black and white snapshot hung in the dead centre of the gallery. In the foreground of the picture is a dinner-suited Jack, his hair greased back in the style of the roaring twenties, his scruffy contemporary look of denim jeans, plaid shirt and wheat-coloured Timberland boots replaced with a dapper black dinner jacket. Behind him is a crowd of riotous Jazz Age revellers — men in tuxedos, women in flapper dresses. As the lens roams further down the photograph we see that Jack is waving. The words scrawled over it read: Overlook Hotel, July 4th Ball, 1921. Practically all of the action so far has taken place in the 1970s. The viewer is left confused. It would be impossible for Jack to be there. Has Jack gone back in time? Is he a reincarnation of one of the guests? Or has he simply been absorbed into fabric of the hotel’s history?

The American literary critic and philosopher Frederic Jameson had his own theory about the movie. For Jameson, the sweeping aerial tracking shot that appears at the start of the movie shows a “quintessentially breathtaking” and “unspoiled” American landscape. The camera moves glacially down the Colorado River basin before rising steeply up the slopes of the peaks as the family’s tiny yellow Volkswagen Beetles winds somewhat camply around the precarious mountain highways and the ski slopes of Mount Hood. As Jameson quite rightly suggests, there is beauty here and boredom. In the car’s jaunty pursuit of adventure, there’s a sense of imminent danger. Next we get the shot of the great hotel itself, “whose old-time turn-of-the-century splendour is undermined by the more meretricious conception of ‘luxury’ entertained by consumer society.” [2] For Jameson, Kubrick’s movie is a work of Historicism: Nicholson’s character, rather like Scott, is a distracted and struggling author who believes himself to be “the great American writer” — a cultural fantasy that is as old as Mark Twain, Edgar Allen Poe and Henry James. Jack doesn’t know this, but the days of Great American writers — or great ‘any things’ for that matter — are gone already. The author, a recovering alcoholic, is stuck in a loop where the last roaring days of the Gilded Age have been frozen on repeat. This is probably why the words that are written over the picture are so important to Kubrick: Overlook Hotel, July 4th Ball, 1921. The cheers that went up annually during the country’s Fourth of July celebrations had always been the echoes of a dying scream. It wasn’t the same for everyone, of course. For men like Warren G. Harding, the annual celebration marked the eternal roar of American Independence. But for others, it was a small pathetic cry leaking ever so desperately from the jaws of a disappearing world that could no longer survive on its former brilliance and past achievements.

Such cold, aloof cynicism isn’t always so easy to understand. The same could be said of any festival or annual celebration, right? Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind? In cultures the world over, our devotion to the past is renewed on a 12-month basis through whatever form of ritual revives our flagging soul and pays off our cultural and national debts — fireworks and drinking optional. The plaid check shirt worn by Nicholson as he manically pursues his wife and son through the building and its grounds, matches the red, white and blue of the American national flag. This is America, and I’m an American it says. It’s also probably not by chance that King’s orginal story had Jack and his family take up occupancy in Room 300 — the ‘Presidential Suite’ — located in the hotel’s ‘West Wing’. In the novel, the room had hosted a long and illustrious array of Presidents, good and bad: Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, Franklin G. Roosevelt and Richard Nixon. [3] Like Gatsby, Horace M. Derwent, the millionaire playboy who bought The Overlook Hotel and turned into the stunning palatial playhouse it was today, had been deeply enmeshed in the violent criminal underworld of New York and Chicago — he was a friend of royalty, presidents and mafia king-pins. The room had its own stories to tell, from the brokering of deals that would turn over millions of dollars to seedy gangland murders and lonely suicides. [4] Beneath the polished floors, grand arches and mirrored-surfaces there is something foul. The money that Torrance imagines rolling down its corridors in The Overlook’s golden heyday has been tainted in some way.

For Jack Torrance, the off-season caretaker of the American Dream, anything worth celebrating in life was already behind him, “somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.” Or in this case, among the snow covered peaks of the Colorado Rockies. Jack pursues his family, just as the past pursues (and ultimately claims) Jack. It’s a common trope in horror movies: the dream has become the nightmare, the house a prison. In the novels of Scott Fitzgerald, as in those of Stephen King, the past clings stubbornly to the present. Jay Gatsby is an anachronism in the same way that The Overlook Hotel is an anachronism, and there’s a huge deception being played by both. Like the guests at The Hotel Cecil’s 4th July celebrations, Jack Torrance isn’t possessed by evil, but by history, a history that leaves its “sedimented traces” in the corridors and “dismembered suites” of the hotel that had once been graced by Presidents like Harding and Roosevelt and Old World families like the Astors, the Vanderbilts, the Rockefellers and Du Ponts. The hotel, which had once throbbed so lustfully with life, now stood now as a “decrepit relic”. [5] Like the clock on Gatsby’s mantel, the place has just stopped ticking. In the end, it’s the supernatural reality of whatever America is that Kubrick is exploring; its many faces, its many layers — its palimpsest or pentimento qualities — a history of America that is “savoury and unsavoury alike”. [6]

Now That Our Love Dreams Have Ended

Someone commented recently that Jack Clayton’s 1974 movie adaptation of Gatsby was full of scenes that looked like they belonged in The Shining. Among them was the one that shows Karen Black as Myrtle Wilson rapping wildly on a window pane with her knuckles until it breaks, then licking the blood off her lacerated fingers. For the first five minutes of Clayton’s film the camera roams through an empty palatial mansion at twilight. There is the thin and rather spectral sound of a distant piano playing and people talking but as the camera moves around it soon becomes obvious that there is not a soul in the house or in the garden. These are the ghosts of a happy moment that have long since passed. Clothes are laid out on the bed, hairbrushes are laid-out for use and there’s an old scrapbook of newspaper cuttings left open on a period bedroom table. As the eerie, echoey laughter subsides, a gramophone starts playing a melancholy tune: “Gone is the romance that was so divine. ’tis broken and cannot be mended. You must go your way, And I must go mine. But now that our love dreams have ended.” ‘What will they do when their love dreams have ended?’, asks the crooner. The answer seems rather obvious: that’s when the nightmares begin. Gatsby begins with the same directorial treatment that ends The Shining: with aching sweet music. The songs, both foxtrots, enshrine one dying moment of bliss when the dream is almost ended and the moment of surrender is upon them. In both, there’s a moment that has been captured and preserved. What the crooners are surrendering to is time itself. The way that Clayton handles ‘the eyes of Dr Eckleburg’ are more macabre still. Anybody who has ever watched an episode of the Twilight Zone, Outer Limits or even the X-Files will know exactly what I mean. The way Clayton had trained his camera on the eyes of Dr Eckleburg and panned out slowly to reveal the Valley of Ashes has all the signature notes of your classic supernatural chiller. The whole thing is probably no accident either. Clayton’s first serious stab at directing had been The Innocents (1961), a genuinely chilling adaptation of Henry James’s ghost story, The Turn of the Screw. Clayton returned to the macabre with Our Mother’s House (1967) and Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) — the two films that sandwiched Gatsby. Clayton, however, was only amplifying themes and motifs that were already present in Scott’s novel. The book’s central character and his friend, Nick Carraway, are men who are haunted by their own pasts. What haunts Nick and the novel’s faintly Gothic hero, are themselves. What comes back to kill Jay Gatsby at the end of the novel is his former life as plain old James Gatz and there are clues to be found everywhere. The young Jimmy Gatz is “haunted at night by the most grotesque and fantastic conceits”. The crawling line of “grey ash grey” in the Valley of Ashes recalls the shuffling, catatonic march of the “crumbling” undead, men who are missing half their souls. Nick walks up Fifth Avenue and feels “a haunting loneliness”. After Gatsby death “the East is haunted” for Nick. At one point Nick even thinks he can hear the music and the laughter of past parties “faint and incessant” from the garden. He thinks he sees a phantom car. And then of course there is the picture the author paints of the “girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs” as Nick drives along 59th Street. Nick is haunted, Gatsby is haunted. The whole of New York is haunted.

Ghosts are mentioned several times in Gatsby, so it may come as no surprise to learn that Fitzgerald was a big fan of Edgar Allen Poe, whose 1843 yarn, The Tell Tale Heart hasat its centre an image that is not a thousand miles away from ‘the Eyes of Dr T. J. Eckleburg’. In Poe’s story the “pale blue vulture eye” of an old man compels his carer, another manic obsessive, to commit cold-blooded murder: “I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye forever”. Even Nick’s arrival in West Egg is conveyed with all the creepy enchantment of a Brothers Grimm folktale. Nick is like Hansel and Gretel. He’s lost his way and finds himself in some “weather-beaten cardboard bungalow” nestled among the trees whose leaves burst miraculously into life upon arrival. He never planned to come here. He has drifted here. The opening chapter of the novel has tropes that have a long and firm tradition: Nick is the governess turning up at Bly Manor, Jane Eyre arriving at Thornfield Hall and meeting Mr Rochester or even the calm and unflappable Jonathan Harker arriving at the castle in the mountains in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Nick Carraway is a man with no manifest destiny at all, a casual traveller with a casual lifestyle drifting aimlessly through his life, his loose-grip on the past marked by some doubtful claim of kinship to some long lost Scottish clan and a sentimental reluctance to let go of the romance of Wilson’s war. A lover of the strange and the mysterious, Scott had found himself producing The Twilight Zone some thirty-five years ahead of Rod Sterling.

Several critics have viewed Kubrick’s film as an allegory on American Imperialism. In Kubrick’s film (but not in King’s book) the General manager of The Overlook Hotel tells Jack Torrance that the hotel had been built on an old “Indian burial ground.” If we accept this, then the movie’s opening sequence takes on an additional resonance: the sweeping glacial shots of Mary’s Lake and the surrounding peaks gives us the rich, natural promise of a landscape carved first by the Native Americans and then brutally swept aside by the mindless advance of modernity and consumerism. What happens next can probably all be put down to karma. The little yellow car driven Torrance is pathogenic, blithely invading an eco-system it neither respects nor understands. Gatsby had his big yellow Rolls Royce Phantom thudering along Queensboro Bridge and Jack has his cute little VW Beetle, a practical and affordable little car that had brought freedom to the masses, and which in Kubrick’s hands becomes a vulgar little symbol of modern times. The hotel has been built upon a sacred site, every bit as precious and arcane as the “fresh green breast of the new world” that is visualised by Nick Carraway at the end of the Gatsby novel. In Jameson’s eyes, Jack doesn’t have writer’s block, it is simply that there are no longer any stories worth telling. [7] The air of modern life is, for the genuine artist, too thin to breathe.

In November 1974, the historian William H. Goetzmann wrote that it was a belief in the future that formed the bedrock of the American Dream. You started with nothing and made something out of it. The boundless wilderness of the western frontier was the land of opportunity and “the strength of the New Republic”. It was also thought to be the source of moral virtue: the people in the wilderness lived closer to nature than Europeans and Nature was God’s creation: “To live closer to nature was to live closer to God. For almost a century Americans felt themselves to be continuously present at the creation.” Scott’s friend Shane Leslie wrote that Estes Park was “a Garden of Eden where the climate was so delightful that the men died only of gunshot”. But at the Overlook, there’s something wrong. This gaudy monster of modern luxury shouldn’t really be here. It’s an anomaly, an invasive species. There had always been fears that building a large resort hotel like The Stanley and the power plants it would rely on for energy would spoil the grandeur of the scenery and the purity of the lakes. The ‘Great American hack’ had found himself being hired, somewhat naively, as the caretaker of the Great American Fake. At the end of The Great Gatsby, the novel’s narrator, Nick Carraway, finds himself staring up at Gatsby’s “huge incoherent failure of a house” and imagines how the Island might have looked to the eyes of the Old Dutch sailors who had landed on its shores when it was still the unspoilt “fresh green breast of the world”. Nick feels a responsibility to return to the house in the same way that Jack feels a duty to maintain The Overlook. Looking among the scrapbooks, the letters and old photos, Jack begins to feel not just a responsibility to The Overlook Hotel but a “responsibility to history” itself. Standing among the cobwebs and the dust, the whole place is screaming with echoes:

“The clink of glasses, the jocund pop of champagne corks. The war was over, or almost over. The future lay ahead, clean and shining. America was the colossus of the world and at last she knew it and accepted it.”

It is not a ghost story, Jameson contends, but the story of a failed writer with a failed dream; someone for whom the ‘idea’ of being a great writer is infinitely more attractive than the joyful pursuit of words around the page, someone who is haunted by the fantasy of what the ‘Great American Writer’ is. [8] It is not an existential crisis that Jack has been enduring, but an historical one: Jack Torrance “is possessed neither by evil as such nor by the ‘devil’ or some analogous occult force, but rather simply by History,”writes Jameson. “You’re the caretaker,” the bartender tells Jack, “You’ve always been the caretaker.” Karma, as many understand it, holds that man is destined to be reborn into suffering again and again and again until he breaks the cycle. King’s ‘meta-ghost story’ peels back those pentimento layers to reveal the portrait of an artist drawing on the addictions and obsessions of a schizophrenic nation fated to repeat its wrongdoings time and time again. For the cheerfully neo-Marxist Jameson, it is not the biting sub-zero temperatures that kill poor old Jack in the end but the collective nostalgia that stales the air and the exhausting banality of ‘late capitalist consumption’ that bleeds through the walls of the hotel. It’s the past coming back to get him.

As Stephen King and his wife settled into room 237 of The Stanley Hotel at the close of the 1974 holiday season, he might have glanced over the day’s newspapers and caught some intriguing and unsettling discoveries. Over in England, the Cambridge-based physicist, Stephen Hawking had some exciting news to announce on ‘black holes’. Contrary to our previous understanding, Hawking had found that black holes could have entropy and emit radiation over very long timescales. All they really needed was constant supply of infalling matter. When they fed, they behaved like super-powered beacons sucking in everything in their path. In America, Princeton’s Professor John Wheeler, the man who had coined the phrase in the late 1960s, was telling the New York Times that the universe would one day collapse into a single black hole with the complete annualization of all matter and all physical laws. The next few years, Wheeler predicted, would be the years of the black hole. At a packed-out McCosh 10 lecture theatre in November 1974, the audience held their breath as Wheeler described the theoretical possibility of an observer looking inside them and seeing time-slowing or perhaps even going backwards. Suddenly, everyone was talking about these colossal hearts of darkness whose density was so enormous that not even light could escape from them, and whose geometry was so mind-boggling and so peculiar, that it had the ability to warp time. Sci-Fi had a brand new monster.

Kubrick and Clarke had shown a vague understanding of the phenomenon in 2001: A Space Odyssey when their astronaut, David Bowman, enters the giant cosmic worm hole the ‘Star Gate’. Interest in the subject was further stimulated by Joe Haldeman’s 1974 novel, The Forever War, which drew on the author’s personal experiences of the Vietnam War and Larry Niven’s short story The Hole Man (1974). Disney followed suit a few years later with Gary Nelson film, The Black Hole. In nearby Kansas, the Hutchinson Planetarium was transporting its guests to the graveyards of outer space with an interstellar show entitled The Black Holes of Space. The show, which offered a look at the violent death throes of these dark stars, had a soundtrack that included Wendy Carlos’s theme for Kubrick’s earlier film, A Clockwork Orange.

America and Britain’s first encounter with the subject had come in April 1921 with the arrival of Albert Einstein in New York. Just a few days before F. Scott Fitzgerald and President Harding’s new Ambassador to Britain, George Harvey went steaming across the Atlantic to England on the RMS Aquitania, Einstein was preparing for a series of lectures at Scott’s old university, Princeton. The funds raised during the trip would be donated to Einstein’s newly founded Hebrew of University of Jerusalem. His meeting with President Harding at the White House on April 24 couldn’t have been any more awkwardly timed, poised as the President was to raise the gates against the ‘horde’ of Jewish immigrants pouring in from Southern Europe. Harding, as it turned out, had little or no knowledge of Einstein’s theories and was more interested in the scientist’s wild, woolly mesh of hair and his competency on the fiddle. By the Fourth of July, Einstein was back in Berlin, his meeting with Lord Haldane in Britain having him a good deal more intrigued than Harding. By the time he left London in June, the Goethe-loving British Statesman was heralding the ‘reign of relativity’: measuring rods and clocks would soon be a thing of the past.

The series of lectures taking place between May 9 and May 11 at Princeton that year were America’s first introduction to Einstein’s ‘Theory of Relativity’. It was Einstein’s work, supported by the findings of Karl Schwarzschild, that would give the world its first real glimpse of light defying, gravity-defying, time-bending super dense objects that consumed and distorted anything they came into contact with. At a figurative level, these crazy collapsing stars were everything that King’s Overlook Hotel was. In 1974, the world was waking up to the fact that things didn’t get any darker or more dangerous than Black Holes. Like The Overlook Hotel they distorted time and destroyed light. With a temperature of absolute zero, it was the cold, dense heart of darkness, feeding off Torrance’s evil and determined to have Danny’s light. What went in there might never come out. Nothing could escape it. With the corridors that stretch back through time, and a West Wing as cold as the arctic, The Overlook Hotel is the hungriest house in the world. After being pulled into hotel’s gravity well, there was never any real chance of Jack Torrance coming out intact.

Instant Karma

In February 2018, King faced a backlash on Social Media when he Tweeted his response to the news that dozens of Republican members of Congress, including House Speaker Paul Ryan, had been involved in a fatal train crash. Even by the standards of Social Media, the 112 characters he hammered away at his keyboard that day were fairly harsh: “A trainload of Republicans on their way to a pricey retreat hit a garbage truck. My friend Russ calls that karma.” King later apologized for the comments and the whole thing was soon forgotten. Russ was Russ Dorr, King’s researcher and medical advisor, and someone he had known on and off since the summer 1974. It was an interesting comment in the circumstances. According to King it had been, Instant Karma, John Lennon’s belligerent anthem of fast-acting karmic justice that had inspired the title of his book, The Shining. The song had been written and recorded by Lennon on January 27, 1970. John and his wife Yoko had just returned from a month-long holiday in Denmark. On their return on January 24th, Lennon was most likely faced with a barrage of calls and invites from his friends in the New Left Movement. Tariq Ali, who Lennon had known through his contact with the ultra-wing Left Wing newspaper Black Dwarf, was organising a torchlight demonstration in London on the 25th.

Ali had grabbed the headlines the previous year when 705,000 people poured onto the streets of London to protest against the war in Vietnam. The National Union of Students boycotted the event. A statement issued on October 23 outlined their concern: “The trend to violence must be halted. Ignore the demonstration. It won’t help the Vietnamese.” The slogans shouted that day had been a major embarrassment to Britain: ‘Victory to the National Liberation Front’ and ‘Death to American Imperialism’. In his book Street Fighting Years, Ali recalls inviting Lennon on the marches to sing, but that Lennon would refuse on account of the free for all rampage that breakaway groups would always threaten to embark on. The demo that went ahead on January 25, had again been organised under the banner of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign. This time however, the movement was protesting against Harold Wilson’s deeply controversial meet-up with Republican President, Richard Nixon at the White House. The date that had been set for the summit was January 27, the very day that Lennon sat down at his piano and hammered out his wall of sound peace anthem. Tariq’s procession gathered at the Charing Cross embankment before clashing with police at No. 10 Downing Street. This was not just some stunt to amuse the press. The New Left in Britain had been feeling completely and utterly betrayed by Wilson ever since he had scraped a narrow victory for Labour in the 1964 elections. Writing in Black Dwarf on the 16th, its editor Tariq Ali applauded the success of the Tet Offensive led by the Vietnamese some twelve months before. The meeting between Wilson and Nixon on the January 27th was a meeting of ‘war criminals’ and direct action was being demanded to stop it taking place. Just two months earlier, Lennon had sent back his MBE. The letter, addressed to the Queen and written on notepaper headed ‘Bag Productions’, explained his motives: “I am returning my MBE as a protest against Britain’s involvement in the Nigeria-Biafra thing, against our support of America in Vietnam and against ‘Cold Turkey’ slipping down the charts. With love. John Lennon of Bag.” The ex-Beatle and his wife had followed it up with a global anti-war poster campaign. The words, written in bold black and white lettering on giant billboards, spelled out his vision for peace. It was as brave as it was simple: “War is Over. If you want it.” Just to ram the message home, the couple had smaller A5 version printed up and mailed to Wilson as a Christmas card that year.

According to Lennon, he had sat down on the morning of Tuesday January 27 in a state of total possession: he didn’t just want the song written that day, he wanted it recorded and banged out on vinyl that day. He was clearly pumped-up about something. As Wilson sat down with ‘Tricky Dicky’ Nixon in the Cabinet Room for talks, Lennon convened his congress of musicians in Studio Three at EMI Studios, Abbey Road: Lennon on vocals, acoustic guitar, George Harrison on electric guitar, Billy Preston on keys, Klaus Voormann on bass, and Alan White on drums. What had stood out for the author Stephen King were the words of the chorus: “And we all shine on, like the moon and the stars and the sun.” Whether Lennon ever really had a complete philosophical grasp of ‘Karma’ as Hindus had understood it, it was, nevertheless, a sincere and battle-weary appeal for some kind of cosmic understanding between the peoples of the world. In Hinduism, Divas are quite literally ‘the Shining Ones’. Even Chandra, the moon god, shone bright in the night sky. Light was a positive energy that radiated right across the world. To add a bit of weight to the chorus, a lively throng of revellers were dragged in from a nearby nightclub. Sound engineers and roadies, and practically anyone hanging around added their voices to the mix. By midnight, Lennon and his producer had the wild, clanking chorus they were looking for. The whole fiery spirit of the song was complete. Some years later King would explain the meaning of the phrase as he had used it in The Shining: “The shine” is a psychic ability that enables those who have it to read minds and communicate with other shinning users through the mind, and allows them to see events that have happened in the past as well as those that will happen in the future.” If the world were perceived correctly, then the past present and future would be experienced in a simultaneous, cyclic state with the instantaneity of light. Reincarnation was only the outward manifestation of an internal psychic challenge.

Lennon’s song however, just like King’s book, is based around two opposing principles: the peace-loving desire for hope, connection and brotherhood and the no less passionate cry for instant accountability — of scores to be settled, and debts paid, right here, right now. In contrast to the warmth and benevolence of the chorus, the curt, snarling verses crackle with threats and violence: “Instant Karma’s going to get you, Going to knock you right on the head, You better get yourself together. Pretty soon you’re going to be dead.” Any scores to be settled should be settled right now. The karma of the 21st Century should be as easy to produce and consume as instant coffee. For a generation defined by its need for ‘instant gratification’, it was the most natural thing in the world. It was the speed and simultaneity of the concept that appealed to Lennon and his fans. Filtered correctly, ‘instant karma’ could be ferocious — the kind of karma that King might have been looking for when it came to a trainload of Republicans.

Banging the song out in a day had been crucial to getting the message across: those responsible for the Vietnam War — whether it was the soldiers themselves of their leaders — would be paying for their actions not in the future but now. Lennon had already made it clear back in 1968 that he had always been in two minds about the need for direct action. During The Beatle’s performance of Revolution on the David Frost show on September 8th, 1968, Lennon had got to the line, “But when you talk about destruction, Don’t you know that you can count me out” before adding cryptically, ‘IN’. Appearing on the show just 48 hours earlier was Tariq Ali. In January 1969, Black Dwarf’s music critic John Hoyland had done his level best to bait John into backing violence by playing on his ego. In an open letter Hoyland had said that The Beatle’s song Revolution was no more revolutionary than ‘Mrs Dale’s Diary’ — that John was, to all intents and purposes, a bit of a tourist, a bit soft. The critic trotted out the usual anarchist creed that to make the world a better place you first had to destroy it ‘ruthlessly’. Much to Hoyland’s surprise Lennon wrote back. In an open letter that was published the following week, Lennon handled the charge pretty skilfully. He asked Hoyland to name a revolution that had changed lives for the better. It wasn’t regimes that had fucked-up Communism, Capitalism, Buddhism or Christianity, reasoned Lennon, it was people. Grouping other humans and societies into an in-group or an out-group — an ‘Us and Them’ — was at best ‘naïve’ and at worst, narrow-minded. His PS at the end of the letter ranks as one of the sharpest comebacks in magazine history: “You smash it, I’ll build around it.”

Shortly before his death in 1980 Lennon clarified his position on the war on Vietnam and the couple’s understanding of ‘karma’ at that time, both of them agreeing that everybody, no matter who, had their own karma to deal with — especially those who backed and fought in the war: “there are the poor ones that didn’t follow their instincts and went to Vietnam and got killed, crippled, and deformed and only woke up afterwards. That’s the responsibility of the people that not only sent them there but sent them there under an illusion.” Being under the influence of the dream or Nixon’s spell was no excuse. Not to Lennon. Interestingly, there’s some indication that the phrase ‘instant karma’ was already being used by beat poets and musicians in New York in the late 1960s either as something good or something bad. In one column someone writes that some of the more “underhand” activities they’d been engaged in “had shortly backfired — a sort of instant karma”. When Nixon had visited Britain in summer ’69 he had dutifully rolled out the message that Britain and America were “partners in a quest for peace.” If they were, then they clearly pursuing peace in the same manic, murderous fashion as the axe-wielding Jack Torrance.

As Wilson and Nixon met in the White House, news had begun to emerge of US soldiers getting high and going on crazy killing sprees. The whole idea would be explored more fully in Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986), Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987), and in Steve Miner’s haunted house caper, House (1985). Karma had been at the centre of practically every ghost and every horror flick since the 1800s. It doesn’t matter whether its Shelley’s Frankenstein, Dicken’s A Christmas Carol, The Phantom of the Opera, or even Carrie; to one degree or another they are all driven by karmic justice. Everybody was going on about karma the ’60s,” Lennon explained, “but it occurred to me that karma is instant, as well as it influences your past life or your future life. There really is a reaction to what you do now. That’s what people ought to be concerned about. Also, I’m fascinated by commercials and promotion as an art form.” In the end, everything came down to taking responsibility for your actions — before karma took care it of it for you. King and Lennon appear to have been in agreement about one thing: the future, however bleak, or however brilliant, was something you inherited. In a sinister twist, Ali’s partner in Black Dwarf, the literary agent, Clive Goodwin would die in Police custody in Los Angeles, after travelling to Hollywood with his client, Trevor Griffiths. The pair had spent the week discussing the script for the film, Reds, the movie that charted the career of Ten Days that Shook the World author John Reed and his wife, Louise Bryant — a good-time friend of the Fitzgeralds in France. The film would be released in December 1981 and star The Shining’s Jack Nicholson as the playwright Eugene O’Neill and The Great Gatsby’s Edward Hermann as Max Eastman.

On April 14, 1912, the day that RMS Titanic surged across the Atlantic at 20.5 knots per hour into the cold hard reality of a seemingly invisible iceberg, the New York Times printed their review of The Promised Land by successful immigrant author, Mary Antin. The book, an account of Antin’s early years in the Jewish ‘reservations’ of Russia and the family’s ‘dream’ escape to America, had been published just that week by the Houghton Mifflin Company. The book concluded with a line that has been coded and re-encoded into the codex of the American Dream for generations: “it is not I that belong to the past, but the past that belongs to me. America is the youngest of the nations and inherits all that went before in history … Mine is the whole majestic past and mine is the shining future.” [9] Antin was experiencing the ultimate in karmic connections. For a boat in which 90% of its passengers were dreaming of starting a new life in the ‘promised land’ of America, Antin’s language seemed strangely prophetic: she had emerged from “the dim places where the torch of history had never been” and would navigate her journey forward using only “the stars of the night and salt drops of the sea.” The historian James Truslow Adams, who is generally recognized with having popularised ‘the American Dream’ as a capitalized stock phrase in his 1931 book, the Epic of America repeated Antin’s speech word for word, hammering it like gilt onto the cover of US history forever.

A Responsibility to History

I’m not suggesting for one moment that The Shining, whether its Kubrick’s movie or King’s novel, is a simple allegory of Isolationism under Harding, the Cold War under Truman or a metaphor for the ‘Shining Future’ of the American Dream — not in any consistent or deliberate fashion, anyway. Sometimes a writer finds themselves in receipt of something that’s been passed down to them like an heirloom. The themes and images that are buzzing around their brain are not always their own but part of a collective memory. The dreams they dream often bleed through from obsessions and traditions that have been learned from other books. Authors and directors are no different from the rest of us in that they will often see themselves reflected in the patterns and behaviours of the world they have inherited. They seek parallels and listen for echoes. Just as earlier civilizations looked for meaning in the random alignment of stars, we may look for pathways and green lights in the mad, chaotic, low-latency flow of pop songs on our Spotify playlists or in the conflicts, goals and challenges being played out on The Walking Dead. Something that not only chimes with our lives but provides some kind of explanation, and just occasionally, a solution. Our daydreams acts as the switches, routers, translators, and changes between the network cabling, fibre, and the endless transmission of data that we shape into the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. The cycle of self-abuse experienced by the alcoholic becomes the cycle of abuse experienced at a national level. Your isolation becomes America’s isolation. The zombie banging at your door becomes the boss giving you hell at work or the bully at school giving you a bashing. Lose your job and within weeks you may suddenly find yourself energized by the atrocities going on in Gaza, or Putin’s assault on Ukraine. Get another job, and all the problems in Gaza or Mariupol disappear. The micro and the macro trip and collide with a spirit of reciprocity that borders on the OCD. And inevitably over time, the boundaries between intervention and documentation, and between the micro and the macro become blurred and ambiguous. We both absorb and are absorbed by our environment. It shapes us and we shape it. As King would observe about The Shining, “the inner weather mimicked the outer weather”. Cultural artifacts are not just things you find in museums. We too are artifacts of sorts; a collection of stored procedures and stored values, occasionally twisted by emotion or shortfalls in understanding, but ones which are usually preserved one way or another by the range of creative measures we take to either support them or resist them. The ‘responsibility to history’ that Jack talks about in The Shining is like a browser cache that we just can’t clear.

The full emergence of the ‘Great American Dream’ only really took shape in America as part of public discussion on the legitimacy or illegitimacy of the Vietnam War. Go to any newspaper archive online and key ‘American Dream’ into the search bar and see how many results are returned when you filter it by year. You’ll notice a huge surge of hits between the 1971 and the 1978 period. Its probably fair to say that things only really gain ground as concepts or ‘ideas’ when they meet resistance that is equal to or greater than the support they have. Whether the attempt is to validate something or invalidate something, it will validate it all the same. Politicians know this instinctively when they say let’s not talk to the terrorists because it risks legitimising terrorism. Don’t give it column space. Starve it of oxygen. The folks in publicity know this too: all publicity is good publicity. Opposition to the Vietnam War began to increase rapidly after the Tet offensive in 1968. The election of Richard Nixon the following year also increased opposition. It was around the time that opposition and support for the war began to balance out in 1971 that the idea of ‘the American Dream’ fully matured in the public consciousness. The phrase had stakeholders in both camps, and both camps started using it as a prop in discussion: the ‘American Dream’ had been lost, the ‘American Dream’ was still alive. Suddenly the idea had flesh. As soon as you started saying the ‘Dream’ no longer existed, you saying that it was real: it may not be alive now, but it had been alive in the past. Speak of the devil, and the devil is at your elbow. The result was that even if the American Dream — as some incorruptible ideal — hadn’t existed until this point, it existed now. Just as in the 1919 to 1926 period, the thing that got people talking about ‘the dream’ and breathing life into it as an idea were the number of body-bags that were being brought home from abroad. Whilst discussion about ‘the dream’ had previously been confined to historians like James Truslow Adams, and lyrical New Romantics like F. Scott Fitzgerald, the people talking about it now were ordinary Americans. The 200 year anniversary of the War of Independence on July 4, 1976 sealed the deal. Returning from a Fourth of July tour of Valley Forge, Philadelphia and New York, President Ford said he said seen something rather remarkable — a “new reverence and a new sense of the American Dream growing in the land”. The “Great American Dream could at last become a reality”.

An address given by Judge John A. MacPhail to a congregation in Gettysburg on a Sunday in March 1976 is typical of ‘dream’ chatter at this time: “Many people ask some soul-searching questions, one of which is whatever happened to the American Dream?” MacPhail duly acknowledged that such a question required a definition of terms because the American Dream may mean one thing to one person and something else entirely different to someone else. MacPhail’s own idea of what the dream was had been built around Memorial Day parades and the daily sacrifices made by his parents to ensure he got to school, got to church and had good food in his belly. To him it was the ‘Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave, a land of fruited plains, a land of pioneers, a land of hope’. But if that was true, he said looking around him, then it was clear that the dream had now ‘disappeared’. It was no longer the land of the free because a man was no longer free to do what he pleases. He was too hemmed in by “zoning restrictions, planning restrictions and deed restrictions”. The other reason, the bigger reason, he continued, was that America had ‘run out of dreamers’. Dreaming was something that need to be encouraged. The people who made dreams come true were those ‘looking out of the school window when they should have been looking at the blackboard’. Just weeks before America pulled out of Vietnam in April 1975, the McInistosh County Democrat had asked its junior readers what they thought of the ‘American Dream’. One of the children said that the American Dream was the kindness deep down in someone’s heart, the love that two people share, the mothers gratitude when her boy returns home after being a POW or MIA. For another it was the day when divorces were ‘eliminated completely’ and when families could stay together, a place where you weren’t afraid to walk down the street at night. Practically every one of the contributors said it was a dream that that could never come true. Nevertheless, like so many other things that aren’t real, it it possessed a tremendous power.

When the author Stephen King checked into the Stanley Hotel in October 1974, he had been drinking heavily for years. The death of his mother in December the previous year had seen him pour his energies (and his beers) into writing. Faced with a swelling writer’s block, King and his wife Tabitha moved to Boulder in Colorado, a remote and rocky wilderness that couldn’t been more different than the couple’s cosy, suburban hometown of Maine. Boulder, a university town, was experiencing a nightmare of its own. Just a month after King’s first novel Carrie was published in April, six ‘Chicano’ activists had been killed when their parked station wagon exploded just southwest of Boulder Park. Local police would report that the victims, who were composed of current and former students at Colorado University, had been ‘bomb crazy militants’ operating on the fringes of the University’s United American-Mexican Students, claims which were denied by the UMAS leaders, who were utterly convinced that the six had died as part of a right-wing plot to discredit the group who had been campaigning against the war in Vietnam, police harassment and inequalities on campus. The dream for them was something that was offered to others but not to them. Federica Pena, a lawyer for the Mexican-American Legal Defense Fund said two University of Colorado co-eds claim they overheard a Boulder police radio conversation just after the second blast, in which officers said several Anglos had been seen throwing something into the car belonging to the victims.

In December that year a pipe bomb was found in a van owned by Mexican activist, Andres Calderon as he attended a meeting in nearby Greeley. Calderon had stumbled on the 18-inch long device in the engine compartment of his van. A lawyer representing Calderon’s CASA organisation believed the bomb had been planted by “the same right wing forces” responsible for the bombings in Boulder earlier in the year. Just a few years earlier Calderon had drawn the wrath of Joseph Coors, a member of the powerful Coors brewing family who held what many regarded as ‘fanatical’ right-wing views. During his time as Regent at the University, Coors had tried his darndest to suppress militant activity among students on the campus. In response, Calderon had organized a series of boycotts against Coors goods, latching it on to environmental issues associated with the building of new plants used by the brewing giants. Just four days before the first bombing, Calderon had been due in court to face public order offences dating back to the previous summer. In King’s finished novel there is an enigmatic reference to Coors beers and the radical right-wing nativist, Warren G. Harding: “In 1922 Warren G. Harding had ordered a whole salmon at ten o’clock in the evening, and a case of Coors beer. But whom had he been eating and drinking with? Had it been a poker game? A strategy session? What?”

At the time of the bombings, the University of Colorado newspaper in Boulder was advertising two films that were going to be playing back to back at the Basemar Cinema on the southern fringes of the campus. The films were Robert Clayton’s The Great Gatsby, starring Robert Redford and Mia Farrow and The Exorcist with Max von Sydow and Linda Blair, both films having been released within weeks of each other back in March. The King of Terror had arrived in the town just as fear and loathing was at its height and ‘the dream’ had never seemed so real.

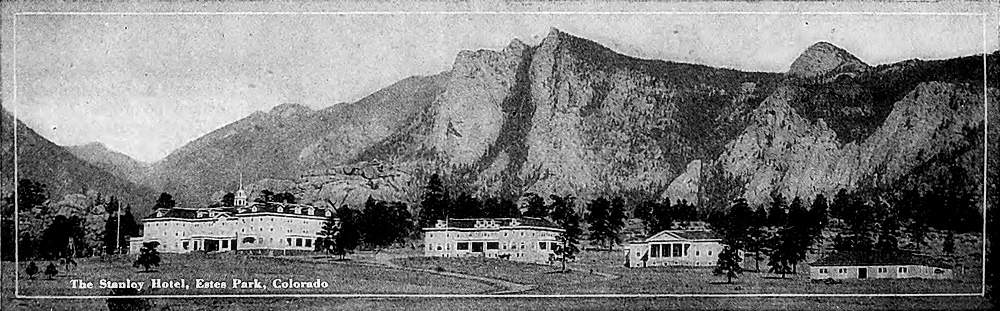

The Real Overlook Hotel

Like Jack Torrance and his wife in The Shining, the Kings are believed to have taken rental of a house on Arapahoe Avenue on the eastern side of town. As in the book, most of the properties on the street were occupied by students at the university and King took an office on the western side of town to work on his book. At this time of year the Flatiron Mountains that he could see from one of the windows would have had a fine dusting of snow on them. To make ends meet, King looked for part-time work, expressing his interests to Boulder’s local newspaper, The Daily Camera in providing movie reviews. The paper didn’t write back and King got down to producing 3,000 words a day for his novel. Despite the words coming quickly, he found himself thinking of his early days as a writer and his struggle to hold down a job as teacher in Maine. One weekend, the couple booked an overnight stay at the recently refurbished, Stanley Hotel, a sprawling and empty glamour hotel located some 40 miles north of Boulder in Estes Park which, rumour had it, was haunted. The hotel and its secluded, snowbound setting, would become the inspiration for The Overlook Hotel, the hotel with dark and murderous history and a past that is set on repeat.

In real life, the hotel had been built by motor-engineer Freelan Oscar Stanley and had been opened in June 1909, just in time for the Fourth of July Day celebrations when Taft was still in the White House. Just two years later the building was partially destroyed when a gas explosion ripped through the second floor of the building, seriously injuring several of its staff. Elizabeth Williams, a chambermaid, was said to have been blown all the way from the second floor to the dining room. As a result the West Wing of the building had to be completely rebuilt. For the next thirty years the hotel changed hands several times, the strangest bid coming in the mid-1940s when Guy Ballard’s I AM religious cult made an offer of $350, 000 to purchase the hotel from its then owner, Roe Emery. Concerned by the group’s interest in the paranormal, the occult and their aggressive anti-war activities, Emery wrote to his friend Clyde Tolson, a senior official at the FBI, outlining his worries. Ballard’s teachings included significant nationalistic and subversive elements. According to Ballard’s teachings, the rituals practised by the group would allow the United States to lead the world into a new golden age of civilization, which would take its cue from the American Declaration of Independence. It would be through these rituals that the group would fulfil the ‘cosmic destiny’ of America. As executive members of the National Services Commission, Emery and Tolson would have concerned, quite naturally, that any conservation project undertaken in the National Park region, should adhere to the core principles of freedom and equality. At the time, Emery was mourning the loss of his wife Jeanette who had been killed in a head-on collision on an icy road in Nebraska in January the previous year. The Emerys were well known to Native American traders in this section and had been in the habit of purchasing rugs, jewellery and other Indian wares for sale in the hotel as tourist souvenirs. It was whilst returning from one such purchasing trip that the accident happened. Thankfully Emery staved off all attempts by Ballard’s crazies to hijack the American Dream on his patch.

Ballard’s principle base at the foot of Mount Shasta in California had been enshrined as a sacred mountain and supernatural site long before the arrival of the first American settlers. For some it was the centre of a cosmic ecosystem, home to swirling vortex energies and fantastic spirit-creatures. An FBI report dated February 1942 reveals that Ballard’s son Donald, the new ‘Crown Prince of the group’ had moved a branch of the cult to Boulder on the pretext of managing the Springdale Mine. Guy Ballard is rumoured to have been obsessed with gold, and after his death in 1939, his son Donald had inherited that same obsession. A tip-off had told them that the group had rolled into town with 1,000 rounds of 30-30 calibre ammunition, but it was not known how many rifles they had. Nevertheless, hysterical rumours had begun to circulate that they were planning a bombing campaign. Whilst it’s impossible to know what qualities of The Stanley Hotel had attracted Ballard and the group, it was the night that King and his wife spent alone in the building that gave him the inspiration for The Shining novel. The hotel was preparing to close for the season and the couple soon found that they had it to themselves. After wandering around its deserted corridors, King had had a vivid, terrifying dream in which his three-year old son was being chased down its endless, maze-like hallways, screaming. His original idea for the book had been based around a story in which a boy had been gifted with the power to make his dreams real. For purely practical reasons, the setting would be switched from an amusement park to a sprawling, snowbound hotel in winter. The more he connected with Torrance, the more he realised he was an addict.

As any addict knows, the best way of kicking an addiction is by kicking the cognitive, cultural and behavioural patterns that kept the addict and their daily rituals stuck on repeat. Addicts will often have other addicts in the family. It’s not uncommon to hear things like, “It’s in the genes … my father drank and his father before him drank.” Jack says the same thing himself. National obsessions are little different. The choices that Torrance and post-war America were facing were like those of any addict. On the one hand they could move toward the light of a bright, shining future or they could recede into “the dim places” where the torch of history had never been. Flashlight or flaming beacon, the occult light of Lady Liberty kept waving, and for those who looked for it, America’s ‘shining future’ was the only true means of escape. As Torrance says in King’s novel: “the future lay ahead, clean and shining. America was the colossus of the world and at last she knew it and accepted it.” [10] The bone-cracking break in time that the Torrance family experience at The Overlook Hotel was a “clean sound with the past on one side of it and all the future on the other.” It’s a novel that begins with high hopes and ends in horror. The tears shed by Wendy Torrance at the very beginning of the novel are “in grief and loss for the past, and terror of the future”. [11] But as we find in Franklin J. Schaffner’s 1968 movie, The Planet of the Apes, which begins like The Shining with a roving aerial shot along a winding Colorado River, the future isn’t always ‘the promised land’ that everybody has been looking for, and the ‘shining’ light of Lady Liberty can end up in pieces on the desolate, lapping fringes of the ocean with only rifle-waving apes for company. The reality of the dream is that it’s often very difficult to know which is the more terrifying: the land of the ‘majestic past’ or the land of the ‘shining future’? [12] Whether it was the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock, the ‘wafer of a moon shining over Gatsby’s house’, or next year’s ‘shining motor cars’, the light of progress and inspiration that pulled you forward was only ever equal in force to the cosy, dim comforts of the past that dragged you back.

There is a moment in the novel in which Wendy Torrance is asked by the five-year old Danny, if she really wanted to go and live in that hotel all winter. “If that’s what your father wants, it’s what I want”, she replies. It’s not intentional, of course, but the question being asked helps us to understand the often arbitrary rules of loyalty and responsibility that will often obstruct the wilder ambitions of self-determination — either at a personal or cultural level. It might be the family, it might be work, it might be the assumptions that we make about our own self-identity — ‘I couldn’t do that, it wouldn’t be me. What would my parents say? What would my husband say? What would my friends say?’

There’s a line in the Colorado state song, Where the Columbines Grow that chimes with King’s novel. The poem, written by schoolteacher, A. J. Fynn in 1911, tells of the poet’s impulse to return to the peaks of Estes Park after spending some years away: “a haunting feeling grew of duty left undone.” There is an echo of this sentiment in George Sefaris’s Return of the Exile, a few lines of which appear in King’s second novel, Salem’s Lot: “After those many years abroad you come with images you tended under foreign skies.” In Fynn’s Colorado Rockies, Jack — and maybe even King himself — had found the fairyland of old romance, a place where age forgot its years. A timeless, spotless place that’s built as much from his imagination as from the roots and soil of the place itself, and from a bond that is as deep and as needy as any romantic attachment. The sighs and screams of the characters come from a remote and a dimly remembered region of the American psyche and its past. They are the sound of the exile returning, the great Odysseus battling with the monster within.

In the context of The Shining, Estes Park is the ideal place for a desperate young writer like Torrance to settle the debts he feels he owes himself and the world. It’s also a world that is empty and expansive enough for dreams as big and wild as Jack’s to come true. As he braces himself for throwing in the towel and getting another job, the image he had fashioned of himself in the future comes back to haunt him:

“The picture of John Torrance, thirty years old, who had once published in Esquire and who had harbored dreams — not at all unreasonable dreams, he felt — of becoming a major American writer during the next decade with a shovel from the Sidewinder Western Auto on his shoulder, ringing doorbells … that picture suddenly came to him much more clearly.”

Not everyone in America sees ‘the dream’ as clearly as this, nor does everyone think they are ‘unreasonable’. When F. Scott Fitzgerald sat down to write his disastrous comedy drama about a simple railway clerk who is accidentally made President of the United States, he was drawing on a chapter of Prejudices by H. L Mencken. Writing in his third volume of Prejudices in 1922, Menken noted that everywhere he looked he was being bombarded with the message that if a man wasn’t happy in America, then it wasn’t because of the inadequacies of the system but because he was insane. Mencken regarded the typical American ‘vegetable’ as someone “smugly basking beneath the stars and stripes” being spoon-fed a daily diet of enriching nutrients. To be happy, one had “to be full of a comfortable feeling of superiority to the masses of your fellow men.” Mencken viewed it as the ideological equivalent of gavaging: a tube was rammed down to the stomach and the typical American was quite literally being force-fed things they didn’t want: “the rules were set by Omnipotence and the discreet man observes them”, he wrote. After reading the book, Scott had taken this core message and adapted it for theatre audiences:

“Any man who doesn’t want to get on in the world, to make a million dollars, and maybe even park his toothbrush in the White House, hasn’t got as much to him as a good dog has—he’s nothing more or less than a vegetable.” — The Vegetable, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1923.

For Fitzgerald’s hero, Jay Gatsby, the pressures of fashioning something big and some beautiful from the slag of an inauspicious start in life are no less intense, no less foolish and no less doomed. It is “his instinct toward some future glory” that moves him forward toward success and ultimately toward disaster:

“his heart was in a constant, turbulent riot. The most grotesque and fantastic conceits haunted him in his bed at night. A universe of ineffable gaudiness spun itself out in his brain while the clock ticked on the wash-stand and the moon soaked with wet light his tangled clothes upon the floor. Each night he added to the pattern of his fancies until drowsiness closed down upon some vivid scene with an oblivious embrace. For a while these reveries provided an outlet for his imagination; they were a satisfactory hint of the unreality of reality, a promise that the rock of the world was founded securely on a fairy’s wing.”

Are the pressures of succeeding any more intense in American than they are in other countries around the world? In the end, I don’t think it matters. Menchen and Fitzgerald seemed to think so. Issues of identity and responsibility are certainly more prevalent in American novels. Feelings of national debt, of making good on the pledges made by its founding fathers had been overwhelmingly strong for much of the 20th Century, even if they might have diminished in the new millennium. When Fitzgerald sat down to write The Great Gatsby in 1923, he had been taking inspiration from the Great Plains and prairie novels of Willa Cather and Arthur Stringer. In fact, the man who turns the midwestern farmer’s son, James Gatz into the gold-hatted colossus, Jay Gatsby is Dan Cody — “the pioneer debauchee, who during one phase of American life brought back to the Eastern seaboard the savage violence of the frontier brothel and saloon.” The fantastic conceits that haunt the young James Gatz at night are not experienced in the city, but on along the remote fertile belts of the Great Lakes and in the Nevada Silver Fields. The field of dreams is the field of genes. It is quite literally in the blood. The American author Christopher Bollen once tried to argue that the American Dream was the subject of “every American novel”. It was a “sort of blurry-eyed national obsession with having it all and coming out on top, or in the case of most plot-driven literature, the failures and breakdowns in that quasi-noble pursuit.” [4] And to a large extent, he is right. One of the most overlooked central characters in The Shining is the hotel’s boiler — the hotel (and the novel’s) engine-room, it’s heart. Jack is given special instructions to check the boiler twice a day. Without the boiler the hotel is nothing. There’s a point at which Jack considers rigging the boiler so it blows the whole up. For whatever reason he stops. Protecting the hotel was his job. He was the caretaker.There was no bigger failure than blowing up the building you were supposed to be looking after and this was no ordinary building. In terms of the American Dream, Jack is the caretaker Fisher King. He might have failed in his job at school in curating the ‘world of great American writer’ but he wasn’t going to fail it this time. Jack is the loyal servant of the past, and he is eager to preserve it, regardless of the damage that he may inflict on his family or on his future.

In tests conducted on more than 200 people, scientists at Stanford University found that people who had been told that their genes were bad (even if it was complete bullshit) showed signs of physical deterioration in the weeks and months that followed. It was self-fulfilling prophecy at the level of DNA. Despite all the obvious signs of danger we move forward with blithe indifference. We are all addicts to one degree another: self-addicts, living our lives on loop. The world famous prayer of Alcoholics Anonymous sums up the challenge that everybody (and every country) will face at some point in their lives: God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, Courage to change the things I can, and the Wisdom to know the difference. The tragedy, if there is one, is that in the midst of a mindless, drunk psychosis it is impossible to know the difference: “He was still an alcoholic. Always would be,” concedes Jack. It was the beatings from his old man that were responsible for his temper. The past was a virus. Everything he was had been either been caught or inherited, including his future.

For some, the story ends with a paralysing stalemate. Like Captain Taylor in Schaffner’s Planet of the Apes movie, you can’t move forward and you can’t go back. “Can’t repeat the past?”, asks Gatsby? Like hell you can’t. Addicts do it all the time. And if the polls in America are anything to go by, America is about to do the same foolish thing again. What is that phrase again? Better the devil you know?

Mr Wilson very nearly books into The Overlook Hotel

Back in a real world New York, July 4, 1921 was the hottest day of year so far and was marked by a wave of loud but peaceful demonstrations. The first of these, The Free Ireland Parade, had set off at 9:45 a.m. from 8th Street and 5th Avenue, through Central Park and ended at Sheep’s Meadow. Only American flags were waved and around 50 bands strode proudly ahead of each procession. The second and more testy of these was the anti-Prohibition Parade when 14,000 protesters tramped the two and half miles of sticky asphalt, maintaining their right to booze and delivering the occasional barbed gibe to officials as they continued to Washington Square. The city’s mayor John Francis Hylan, obviously relieved that the whole thing had proceeded with the minimum of fuss, was telling the newspapers the following day that the Fourth of July Day celebrations had erupted in a spontaneous ‘outburst’ of democracy. The banner being held by the anti-the Dry Act protesters is likely to have appealed in equal measures to Scott Fitzgerald and Jack Torrance: “We hold the 18th amendment is unconstitutional: if this be treason, make the most of it”.

Fans of F. Scott Fitzgerald may be interested to learn that the original owner of The Stanley Hotel, which, as we already know, King had drawn on for inspiration for his novel, was Lord Dunraven. Dunraven had been an associate of Scott’s close friend and mentor, Shane Leslie when Leslie was pushing the Home Rule interests of the moderate Irish Nationalist, John Redmond in the US. [13] In 1919, Lord Dunraven, a die-hard adventurer with a passion for the untamed wilderness of Colorado, was among the few invited guests to have witnessed the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, and the blueprint for the League of Nations, that had given Warren G. Harding — and his case of Coors beers — all the fuel he needed to stoke the fires of American Nationalism and set him on the road to the White House. It was men like Dunraven, F. O. Stanley, Roe Emery and Leslie’s uncle Moreton Frewen, that turned the unspoiled wilderness of the Rockies into the world-class National Park and conservation area it is today.

The Fourth of July celebrations at the Overlook’s real life twin, The Stanley Hotel that year were not a lavish, hellraising affair by any means. In the afternoon, many of the guests had headed over to the old fashioned barbecue with bear and elk meat at the Grand Lake. By way of entertainment was a Wild West show featuring men who had made their name in the annals of Cheyenne performing roping, bull dodging and trick shooting. Staying for the ball that evening were Mr. and Mrs. J.A. Mitchell of Denver and a small party of gents from Washington D.C: L. V. Young, C. J. Lansing, Chester M. Wright and Guy W. Oyster. Joining them that night a hundred or so women delegates of the Pi Beta Bi, broker John Leo Sheridan and his wife of New York and Allen J. Oliphant an Oil man from Tulsa. The night would finish with the usual firework display on the summit of Tolls Mountain when the whole peak would erupt in a fountain of colour. Watching with them that night was wanted man and fraudster, J. H French, whose low-key stay at the Stanley was brought to a no less striking conclusion when three armed rangers stormed the hotel lounge, bundled him to floor turned him over to police.

In May 1920, Alfred Lamborn, manager of the Stanley Hotel, had written to President Wilson inviting him to stay for the summer. The idea was to have the President and his staff occupy the 33-room ‘Manor’ annexe as that year’s ‘Summer White House’. In his letter, Lamborn boasted of the views and the modern amenities: “The manor is situated on a promontory, overlooking a big stretch of the park, and is both lighted and heated with electricity generated in the hotels private plant. Fifteen peaks are visible from the front piazza, the largest single group of peaks in the Rocky Mountain Range.” There were 33 bathrooms, a music room and a billiard room. According to his letter, the hotel was “the last word in modernity”. Wilson’s 1916 opponent, Charles E. Hughes, had spent six days at the Manor and had expressed his ‘delight’ with his surroundings. During his time there, the Republican Presidential candidate would spend his time talking to American newspaper editor and Progressive leader, William Allen White who resided there in the summer. The following year Hughes would accept Warren G. Harding invitation to become Secretary of State.

A short time after mailing his invite, Lamborn received a response from Wilson’s personal secretary, Joseph P. Tumulty, politely declining the offer. The President, who had been most appreciative of the invitation, regretted that it would not be possible for him to accept the invite at that time. [14] In reality, Theodore Roosevelt is the only President known to have stayed at the hotel. Others like Warren G. Harding, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson had stayed at the nearby Antlers Hotel. [15] Who knows, maybe finding himself out of the job to Warren G. Harding in March 1921, Wilson had written back to Lamborn that summer asking if the invite was still open. He may have had good reason to too. After moving his things out of the White House and leaving the fate of the nation to Warren G. Harding, President Wilson picked up a typewriter and started writing. The words, however, did not come easy. The stroke he had suffered in 1919 had left him partially blind and the results of his efforts were said to be slight and disappointing. Like Gatsby, he had probably lived ‘too long with a single dream’. By his own admission he had ‘ideals’ and ‘nothing but ideals’. Wilson’s obsessive hopes of securing world peace had come up against the cruel, raw reality of domestic policy. His rational judgment had been destroyed. Friends were reporting that his mental health had been on the slide for years, that the illusion he had created and the dream he had sought had eventually overwhelmed him. By 1919 there were those who thought Wilson had begun to lose touch with reality. If the word of his closest advisers are to be believed then that voice, once so quiet and precise, would alternate violently between whines of self-pity and petulant screams. By the late 1920s these claims about his mental health were being backed up by Wilson’s former adviser, William C. Bullitt and Sigmund Freud who planned to publish a book on the subject. Bullitt, who had provided intelligence support to the White House at the time of the Paris Peace Conference, was of the opinion that Wilson had ended his presidency with a smouldering ill-temper, ‘full of rage and tears, hatred and self-pity’. Bullitt would provide a breathtaking account of his life at the centre of all this madness in his 1950’s memoir, The Shining Adventure. According to Bullitt, he no longer wanted to see his friends, and he no longer wanted to see his doctor. [16] A rousing speech made by Senator Philander C. Knox in Independence Square on July 4, 1921 would only add to his suffering. America had arrived back at the birth of a nation. It stood with head bowed at ‘the Altar of Nationality’. [17] Just a few days earlier, Harding had signed a Senate resolution prepared by Knox that would bring a formal end to American involvement in World War I. The document, signed in Raritan New Jersey, would also reconfirm American opposition to Wilson’s much sought-after dream, the League of Nations. For the full duration of the Glorious Fourth, Wilson stayed in his office at 2340 S Street banging away at his typewriter. Legend has it that a discarded sheet of paper found in the waste-bin of Wilson’s study in the days and weeks after his death showed the strain of a man who was no longer able to revive the effortless promise of his youth or the elusive golden dreams of the nation. According to witnesses, the only words on the sheet, written over and over again in black bold type, marked an appallingly sad finish to a stellar career: ‘All work and no play makes Woodrow a dull boy’.

[1] ‘Americanism, Senator Hardings US Is not too proud to fight brings uproar’, New York World, June 8, 1916, p. 4; Inaugural Speech, President Warren G. Harding, Congressional Record March 04-May 04, 1921: Vol 61, pp. 4-6; ‘Protection of Our Rights in Mexico Urged’, Arizona Republican, March 12, 1920, p.1

[2] The Gold Room was the name of a private dining room at Astor’s Knickerbocker Hotel in New York. In this version of the Labyrinth myth, Daedelus has become the Minotaur he seeks to escape. No amount of inspiration and creativity can lead him out of the maze. Only his son Icarus escapes. Perhaps King had started to feel the same debilitating pressures to produce books to be marketed and consumed that Scott had felt with his second and third novels. Like The Great Gatsby it was King’s third published novel. ‘All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy’? The dream job is becoming the day job.

[2] Historicism in The Shining’, Frederic Jameson, Signatures of the Visible, Routledge, 1992, pp. 112-134.

[3] In reality I believe only Theodore Roosevelt had stayed at the hotel. Others like Harding, Fraklin Roosvelt and Wilson had stayed at the nearby Antlers Hotel.

[4] The Shining, Stephen King, New English Library, 1977, p.158-160

[5] The Shining, Stephen King, New English Library, 1977, p.5-7

[6] Ibid, p.180

[7] ‘Historicism in The Shining’, Frederic Jameson, Signatures of the Visible, Routledge, 1992, pp. 112-134. Interestingly, Kubrick changed the colour of Jack’s VW car in the novel from Red to Yellow – the same colour as Gatsby’s Rolls Royce. Same change occurs with the colour of the ball bouncing down the corridor. Its gold.

[8] The Shining, Stephen King, New English Library, 1977, p.155

[9] ‘The Immigrant: The Promised Land’, New York Times, April 14, 1912, p.228; The Promised Land, Mary Antin, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912, p. 364

[10] The Shining, Stephen King, New English Library, 1977, p.113.

[11] The Shining, Stephen King, New English Library, 1977, p.19-21

[12] Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey beat Schaffner’s Planet of the Apes to an Oscar for the best films and movie scores of 1968.

[13] American Wonderland, Shane Leslie, 1936, pp. 249-251