In spring 1921, the 24-year old author, F. Scott Fitzgerald embarked on a three month tour of Europe with his new wife Zelda. The trip, which would last from May to July would see them loaf awkwardly through several of Europe’s most popular tourist destinations, meet several well-known people, visit a number of literary shrines and hob-nob with friends and associates working at the British and American Embassies. It would also come to an end some weeks prematurely after a disastrous stay in Rome. The trip was meant to be one last final indulgence before the very real demands of marriage and parenthood set-in. Just a few months before, Scott had learned that Zelda was six weeks pregnant with their first child, Frances. The couple left for England on May 3rd, travelling first class on the Cunard liner, the R.M.S Aquitania in what was being reported as a crowded ‘spring exodus’. With a record number of passengers and practically every cabin filled, the press went a little crazy. The inauguration of President Harding in March had marked what was promising to be a deeply fractious period in Anglo-American relations. Claims had been flying around for years that British-American influences in the US were determined to transfer the sovereignty and independence of the United States to a malevolent league in Europe. Harding had been elected on a platform that opposed the League and had made no secret of the fact that he planned to wrestle back control from the Brits — especially their grip on the world’s oil. The stories being told by newspapers that week suggested the ship’s heaving manifest was a sign that Britain was draining American capitals of its most distinguished residents. The whole thing was beginning to sound like some dreadful act of national treachery; the last blinding flashes of a disappearing Gilded Age were streaming across the Atlantic to take up their place in London as gems in the crown of England. From spring until summer at least, their colossal palaces in the Anglo-American colony of Newport, Rhode Island would remain ghostly. It was as if the ship had become some huge floating sifting pan in some sinister and convoluted gold mining heist devised by the Brits. A bowler hatted Moses was leading his people out of Israel — with three cases of luggage and a bagful of swag.

A review of the ship manifest reveals an extraordinary array of passengers. Matthew J. Bruccoli, rightfully regarded as the preeminent expert on F. Scott Fitzgerald, devoted just two pages to Scott and Zelda’s trip to Europe, and made no mention at all of the trip there. I can now reveal that joining Scott and Zelda on the first class A-deck that day were some of the richest and most powerful Anglophiles and Francophiles in North America. For these people, the summer couldn’t come quickly enough. Over the next three months old alliances would be renewed and new alliances formed. The newly wedded Scott and Zelda were living the dream. Shortly after boarding as first class passengers they would have found themselves in the Entrance Hall, the walls drooling with blue tabourette silks and decorated with fluted pilasters. At the other side of the room was a frieze carved with ornate scrolled foliage. The Old World elegance of the R.M.S Aquitania’s first class cabins were just as lavish, the designers having sought their inspiration from the great houses of England and the neo-classical styles of Mayfair houses like Lansdowne House in Berkeley Square. By way of tribute, the previous year had seen the addition of an ‘American Bar’ in the ship’s Long Gallery that connected the Palladian Lounge with the Smoking Room. The bar had been a tasteful yet rebellious add-on, deliberately conceived to appeal to the scores of Americans who had discovered that long, luxurious trips on Cunard and White Star liners were the most comfortable way of escaping the country’s new draconian prohibition laws.

2600 passengers were sailing that day, the largest of the year so far. As Scott and Zelda stood amongst the horde of sparkling, well-dressed Rhode Islanders and New Yorkers they would have seen a fascinating menagerie of ‘personages’ — diplomats, ambassadors, financiers, impresarios, celebrities, and occasionally, those millionaire mavericks who somehow managed to straddle all these groups. Casting their eyes around the smoking room, Scott and Zelda would have easily spotted those who occupied the ranks of the first camp — the diplomats. Amongst these were Colonel Edward M. House, the former advisor to President Wilson who had worked closely with Scott’s friend and mentor, Shane Leslie during the war and had been one of the five commissioners dispatched by the White House to the Paris Peace Conference just two years before.

His sketch in that year’s best-selling gossip-book, Mirrors of Washington would present a tall, willowy man with large, almond shaped eyes whose kindness and ‘excessive optimism’ had been marred by a dangerous curiosity that made him run instinctively toward fires. “Trivial in figure” and ever so slightly “ludicrous”, the book described how this kindly balding man had been flooded with happiness over the compromises he and Wilson had made in Versailles. The League of Nations had not been a principle to him, but an emotion. His own worst enemy was his own heart. Standing alongside Colonel House was his Peace Conference associate, Henry White, the former US Ambassador to France. [1] Orbiting around them were the Count and Countess Raben of Denmark (returning to the Swedish Embassy in London) and Countess Nils Bonde, wife of the Swedish Military Attache in Washington. The larger than life lady under the hat and heavy veil and sipping with little obvious sign of pleasure at her water, is Sophia Augusta Brown, the outspoken and deeply religious widow of Gilded Age icon, William Watts Sherman, a legendary figure in Newport who had played a crucial role in the election of President Theodore Roosevelt. Exchanging awkward, tipsy glances with her is 22 year old socialite and horsewoman, Hope Harjes, the daughter of Henry Hermann Harjes, the French-born polo player and senior partner of the Morgan-Harjes Bank of Paris. During the war, Hope’s father had a played a remarkable role not only in securing loans for the allies but in organizing the Norton-Harjes Ambulance Service used by the Red Cross. Even after the war Henry would become a marshalling force within the American Colony in Paris. As Scott would later say, all the best Americans drifted to Paris eventually. Henry was one of them.

The man talking earnestly to Robert Treat Paine — direct ancestor of the identically named founding father of the United States — is the cherubin-faced millionaire, Hermann Oelrichs, whose Rosecliff mansion in Newport was used in the 1974 version of Gatsby starring Robert Redford. Avoiding the newspaper men in a darkened corner of the room with the dashing General Hogarth is Mrs Frederick W. Whitridge whose daughter Eleanor had married Colonel Norman G. Thwaites, Provost Marshall of the British Military Mission in New York. In more recent years, Thwaites has acquired a certain degree of fame for being the man who had re-recruited the notorious Sidney Reilly ‘Ace of Spies’ into the British Secret Service during the war. According to fellow spy, Bruce Lockhart, the Intelligence Chief had placed Reilly under the wing of Sir William Wiseman, then serving as head of the Purchasing Commission in New York. After embedding him in an office at the Equity Building on Broadway, Reilly would perform a variety of ‘off-the-record’ duties on behalf of the SiS. The bushy-eyebrowed man offering the pair financial advice, by the way, was Ogden Mills, the financier and racehorse breeder who brother-in-law, Whitelaw Reid had served under Taft and Roosevelt as Ambassador to Britain. Mills was on his way to England to join his son-in-law and daughter, Lord and Lady Granard.

Bridging the gap between the diplomats and the more flamboyant ‘arts’ group, who are looking even more flamboyant than ever against the aged oak-panelling and the antique floor standing lamps, is the silky-smooth Otto H. Kahn, a billionaire philanthropist, patron of the arts and arriving as ever, fashionably late. In 2013, Kahn’s gigantic fairy-tale ‘castle’ on Long Island would be used by the film director Baz Luhrmann as the basis for Gatsby’s mansion in his suitably extravagant movie adaptation of the novel. Already in London was Otto’s wife Margaret, who had booked several rooms at Claridge’s. Later in the month, Kahn would follow Scott and Zelda to Paris. According to the Paris Edition of the New York Herald, Kahn had set off with his wife on the afternoon of May 27 from Croydon Aerodrome with Instone Airlines accompanied by golfer, Chick Evans and the former head of British Intelligence in New York, Sir William Wiseman. It was Wiseman, incidentally, who had supported Colonel House in his dealings with Scott’s London host, Shane Leslie during the war. The book, which had been published by Scott’s publisher Charles Scribner the week prior to the trip, provided a blow by blow account of the Paris Peace Conference. Colonel House and his wife, Loulie, would make their way to France a little ahead of the group and book rooms at the Paris Ritz. As Kahn arrived with his family at the Hôtel Plaza Athénée, Scott and Zelda were checking into their no less opulent digs at the nearby Saint James Albany. Whilst in Paris, Kahn and his wife would meet with their daughter ‘Momo’ (Maud) her husband of one year, John Charles Oakes Marriott, a Major in the British Army who had briefly been posted to Washington. A vigorous socialite, Momo would accompany Scott and his friends, the Murphys, on the couple’s later trips to Europe.

Among the noisy ensemble cast of theatrical types that the dapper little Kahn is dominating is theatre actress Maxine Elliott and the silent movie star, Justine Johnstone. Sharing floor space with them is Broadway producer George C. Tyler, actor-playwright Arnold Daly and Claude Grahame White, the hawkish pioneer aviator who is there with his wife, the vaudeville act and singing star, Ethel Levey. Even at just 5 foot five, the German-born banker and former cavalry officer towers over his fawning admirers with his impeccable charm and manners— a swan amongst gaudy, honking flamingos. Flirting boyishly with the actresses is Prince Vladimir ‘Val’ Engalitcheff, the 21 year old son of a wealthy Russian socialite who Scott would get to know more intimately on their eventual return to New York. In the early 1900s, Val’s lothario father Nicholas had served as Imperial Russian Vice Consul in Chicago. At some point during the war, his relationship with Val’s mother, the daughter of a millionaire, had turned sour and Nicholas escaped to Paris to ease the burdens of a tumultuous divorce. Having since remarried, he was now living at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York where he was cheerfully amassing a considerable gambling debt and fighting off claims of fraud. That was the nature of wealth and influence in New York: the pockets one lined with gold often had holes in them. Unless you were a member of a family that had been socially established for generations, this year’s master was often next year’s slave. The only real patch on offer was inherited wealth and even there the stock was falling.

A few years later, Scott would write that even the “intelligent and impassioned reporters of life” had made the world of the rich and privileged “as unreal as fairyland.” And it was no less true of the press. The rich were the golems of the newsrooms, here to perform whatever task you demanded of them, good or bad. It was a world built on the lies you told yourself, and the lies that others told about you. And it was this powerful combination of hubris and unreality that could either sink you — as it did on Titanic — or provide a smooth, unassailable passage to the blessed realms of Asgard, like it did for the Vikings. Even then, Scott had the wisdom to observe that they “enter deep into our world” or “sink below us” there was still this perpetual notion that they were somehow better than the rest of us. Nevertheless, it was a world that Scott had entered into as energetically as he could.

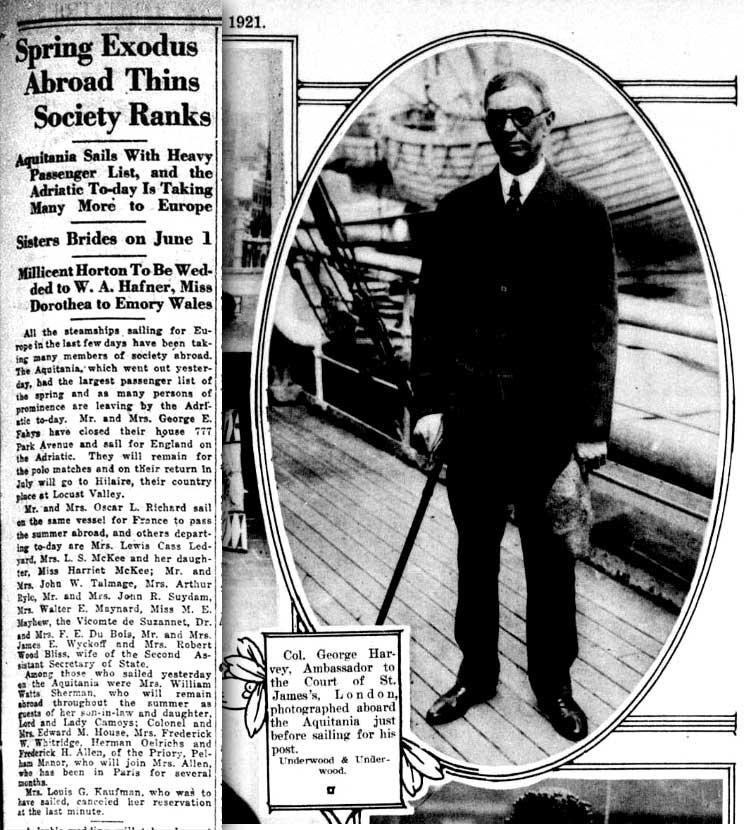

Also travelling with Scott that day was Colonel George Harvey, the brand new Ambassador to Great Britain. A tough-talking American diplomat, Harvey, who was really anything but an anglophile, had been dispatched by President Harding to a take a firmer line with policy — and debts — with their wartime allies. The best selling Mirrors of Washington would describe him as a complete enigma whose “grotesque and elongated shadows” were thrown over everyone who had ever sat on Senate or passed through the White House, a man capable of supporting both great triumphs and great ruins. Scott’s friend Shane Leslie, who would play host Scott and Zelda during their bookend stay in London, thought the bespectacled and top-hatted Harvey rather prickly and bombastic. A book about his life had been published the previous year. The Passionate Patriot, charted his rise from ‘green mountain boy’ into the political and publishing behemoth he was today. The phrase referred to the legendary militias of Vermont who had opposed the English in the earliest days of the Revolution. Ever since, Vermont had been regarded as the “scene and seat” of the most intense American patriotism. If anybody had a bark that was as genuinely bad as their bite it was the flint-faced and owl-eyed Harvey. Their mutual friend Alice Roosevelt Longworth recalled an occasion when the pair had met for lunch in Washington. Harvey had brought her a copy of his magazine, the North American Review in which he “praised God” for Woodrow Wilson before knifing him in the back.

Mirrors of Washington

Back in New York, The Herald Tribune had been excited to share a special dispatch. The headline, printed on the morning of May 17, was as titillating as they come: ‘War Secrets Book Stirs Washington’. The book, which would be published simultaneously in Britain and America that summer, promised to spill the beans on the inner lives and workings of fourteen of the most prominent and respected statesman in America. Twelve months earlier, the British Government had endured a similar storm of embarrassment over an another anonymously authored book, The Mirrors of Downing Street. In Washington, the news about the book was spreading as fast as a virus. Noses twitched and tongues wagged, but despite mounting speculation, nobody had the faintest clue about who was going to feature. For the next few months the identities of the men would remain a tantalising secret that the head-scratching press hounds poured over, and the eminent men of America fretted over. As the New York Times observed, politicians watched ‘covertly, trembling at the potential ruin’ it could inflict. Although nobody knew for certain at this point, two of the men who would appear in the book that summer were on the RMS Aquitania with Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald as they steamed across the ocean to England: Ambassador George Harvey and Colonel Edward M. House.

When the book was finally published in July, it became the fastest-selling non-fiction book in years, partly on account of the hype and publicity generated by the book’s publisher, George Palmer Putnam, who had teased the identity of the book’s authors at the American Bookseller’s Convention in Washington. In an arranged stunt, Putnam said he had something ‘monumental’ to reveal about the writers. As jaws dropped and fingers fumbled for pens in pockets, Putnam asked the author to stand up. Right on cue, nine of Putnam’s stooges sprang to their feet and identified themselves as the author. The room erupted in laughter.

In his 1942 memoirs, Putnam came clean about the whole affair. The 34 year-old publisher had been partly inspired by the boisterous, teeth-bared approach of George Harvey’s Weekly journal, which since its transition from war news to peace news, had been “sticking the pins in the pants of the mighty in Washington”. Harvey had an axe to grind not just with Wilson who he suspected of being in the thrall of Wall Street, but corruption on all sides. There was even an opinion out there that Harvey getting the job of Ambassador to Britain in March had been to keep him away from Washington where he cast his most menacing shadow. Putnam, whose opinion on the outcome of the war and the folly of the Treaty of Versailles had been almost as damning as Harvey’s, had head-hunted the “editorial factotum” of Harvey’s Weekly, John Kirby. When Kirby found that he could not handle writing all fourteen portraits himself, Clinton W. Gilbert of the Philadelphia Public Ledger was brought in to support him. Both men had an intimate knowledge of Washington and understood the often complex nuances of America’s rather ticklish defamation laws. Between 1913 and 1918, Gilbert’s boss at the Herald Tribune had been newspaper magnate, Ogden Reid Mills, whose uncle and namesake, Ogden Mills was on the boat with Scott and Zelda that day.

The fourteen sketches, as Putnam called them, would be supported by some ‘piquant caricatures’ from the pen of cartoonist-propagandist, Oscar Cesare. Putnam described it as “sizzling” stuff but the intent, as sensational as it was, was not malicious. America needed reviving. The nation was unevenly split between extravagant idealism and a debilitating negativity. Putnam’s hope was that these ‘devastating biographies’ would stimulate discussion and provide a fresh appraisal of the personal habits and mechanisms that made great men do not-so-great things, and not-so-great men do things that were even more lamentable. The advertisements being run that summer summed it up perfectly: a chuckling expose of all that was good and bad in American politics. Civilization wasn’t going to pieces exactly, it was simply buckling under the weight of the vanities and the foolishness of those who were leading it and Putnam was braver than most to address it. Over the years, the spin specialists of government have found that the best way of restoring balance is by solving incongruity and reducing conflict, and the safest way of doing that is through humour. The country was in need of therapy.

Even by the standards of satire today, the authors of the book show themselves as shrewd judges of character. The Herald Tribune’s Samuel Abbott would describe a book that bowled “right and left in the alley of National figures”. With the sharpest of wit, the author had managed to get under the “the coats, shirts and collars” of its victims in a way that revealed the ‘all-too human motives’ behind the actions of men in office. With a “whip-snap turn of comment” the book had been able to reveal the “pulchritudes” of the men or had caned the souls of their feet in the memorable and sententious of fashions. In March the following year, Abbott would offer an equally ecstatic review of Scott’s second novel, The Beautiful and the Damned, another “wrecker of routines” whose “shrewd, brilliant, rapier-like” wit “satirised modernity” with all the self-exfoliating energy of a devil in confession.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, Mirrors of Washington appears in the collection of books owned by Scott. Although it is inscribed with his name on the front flyleaf, there’s no indication whether he bought a copy of the book whilst he was in England or on his return to New York. Either way, it is interesting to note that Louise Bryant, the celebrity poet-journalist who Scott and Zelda would get to know much better during their ‘ex-pat’ years in France, would mail a copy of the book to Soviet Leader Vladimir Lenin on her return from Russia in July 1921. That same year Bryant would meet and fall in love with William C. Bullitt Jr, a wealthy Philadelphian who had graduated from Yale with Scott’s friend Gerald Murphy. Between 1915 and 1918 Bullitt had bagged a job as the Public Ledger’s bureau chief in Washington. It was here that be began working closely with Mirrors co-author, Clinton W. Gilbert. As America entered the war, Bullitt’s family connections in Europe gave him entry to some key diplomatic posts and by 1918, the ambitious young reporter had found himself being head-hunted by Colonel House for the Peace Treaty Mission in Paris where he would end up as special adviser to President Wilson. After his dramatic resignation in autumn 1919, Bullitt, like Gilbert, would play a crucial role in how history would remember the President, but for now it was Gilbert and Kirby’s book of biting satire that was creating the same kind of seismic ripples as the ship that was carrying the exodus of American influencers across the waves to England. In the last few lines of his debut novel Scott had written that a generation had grown up to find “all Gods dead, all wars fought and all faith in man shaken”. The country was becoming increasingly split between idealism and nihilism. The passengers might not have known it, but in May 1921, the Old Order was sailing into a crisis.

As Scott thumbed avidly throw the pages of the newspapers in his stateroom accommodation that week, its very likely he would have been piqued by the appalling and fairly obvious failures in pre-trip coverage. Despite mentioning scores of minor celebrities and some virtually unknown society widows, not one line of news had been spared for the much lamented departure of the King and Queen of the Jazz Age. Reviews of his debut novel the year before had on paper at least, turned him into a star. The ‘conspicuously young’ author was the hot new kid on the block — not only the most promising literary talent that America had seen in years, but also its most handsome, most charming and most media-friendly. In all likelihood the pair would have hung around on deck for as long as humanly possible as the press hounds flexed their shutters and performed the usual pyrotechnics with their jostling, hungry flash bulbs. In the end, no one asked him his name and no one snapped his picture. The couple stood there with the look of someone who had turned up at a formal dinner in fancy dress. Among those who did made the picture pages of the newspapers that week were new Ambassador to Britain, George Harvey and Margaret Kahn and her friends, Frances Norton and Elizabeth Sands. Former Ambassador to France, Henry Whit managed to get his face into the Richmond Times Dispatch. Even Harvey’s 18-month old granddaughter was featured waving them off at the dock. The pair didn’t even manage to photo-bomb any of the shots. However much he might have expected it, the sirens didn’t wail, the funnels weren’t painted black as mourning wreaths and the youth of America didn’t weep. From a publicity perspective, the whole thing had been a disaster. And it didn’t get any better in England. The man who had transformed the ‘flapper’ from a crude and sneering insult into a dazzling design for life would be practically ignored by the press for the full duration of the eight-week trip. The glass ceiling was fast approaching. His only hope now was that the ship was a good deal more buoyant than the hype that had bought him the tickets. But before we beat on, let’s drift back a little. What had made him such a star?

The American Rupert Brooke

The new Cunarder had made its maiden voyage just weeks before the outbreak of war. Back then, the 901 ft steamer was being billed as the new Titanic and had entered The Narrows of the Hudson River in an impressive record time of five days and eighteen hours, going from a giant but untested vessel into the most sought-after ship in New York. [1] Scott’s hero, Joseph Conrad had called it a “magnificent ship” that would bear people “unscathed” through ninety-nine percent of possible accidents, something that the 24 year old author is likely to have been very reassured by, obviously. Until now, the confidant young Midwesterner had travelled no further than New York and with the legendary sea disaster of 1912 still fresh in everyone’s minds, it is inevitable he would have been nervous. If he could, he’d have probably picked every troy ounce of gold from the pocket of every second cousin to the Astors that had boarded the ship that day and tossed it overboard, just for the chance it would stay afloat. He needn’t have worried. The pale gold glow of early morning and the pearly calm waters of the Hudson River beneath Pier 54 boded well for a smooth and enjoyable passage.

To understand how Scott had arrived here, is much like trying to understand how the R.M.S Aquitania had arrived at being the luxury floating palace it was in just five short years. Like the ship, Scott had built his precision vessel, rivet by rivet from the keel upward. The only difference was that his shipyard had been the Gothic revival grounds of the Princeton University campus. The price of building something so precious though, was equalled by the effort needed in maintaining it. Although it’s not possible to know the exact price he paid for his tickets, the average cost of travelling first class on the Titanic some nine years before was somewhere around the £500.00 mark (about £15,000 in today’s money). The cost of first class accommodation at the luxury hotels he planned to stay at, like the Hotel Cecil in London, were anywhere from £15 to £20 a night (about £500 today). A skilled worker in London would be earning little more than £10.00 a month, so it’s easy to understand why Scott may have been anxious by the costs he faced on the trip. Just a week or so earlier, Scott had begged his editor Max Perkins for an advance of $600, a modest yet surprisingly crucial addition to the four figure sum he had just picked from The Metropolitan magazine for a serialized glimpse of his second novel, The Beautiful and the Damned. That same day, Scott had picked up boat tickets for the trip and hoped to leave a finished copy of the book with Max before he left. Although it’s not possible to know the exact price he paid for his tickets, the average cost of travelling first class on the Titanic some nine years before was somewhere around the £500.00 mark (about £15,000 in today’s money). [2]

Like the ship, Scott’s debut novel, published the year before, had made the Princeton drop-out an overnight sensation. His publisher, Charles Scribner’s Sons, had been so overwhelmed by demand for the book that they couldn’t keep up with production. The first twelve-months alone would see twelve separate editions. For a book that many of the company’s senior partners had been reluctant to print, the initial run exceeded all expectations. Scribners had thought the cocky 22-year old was good but not this good. Scott’s first draft of the novel, The Romantic Egotist, had been seen as a little rough and chaotic. Scott’s witty and philosophical coming-of-age story wasn’t a novel in the strictest sense of the world but a jumble of recollections that had been squeezed through the crude but instinctive misshapes of prose, verse, lists, letters and even stage play formats. As a result, Scribner had rejected it, but because they had recognized the extraordinary if unconventional talent shown by the young author, they put the usual protocols of the rejection process aside and offered some practical advice:

“We generally avoid criticism as beyond our function and as likely to be for that reason not unjustly resented by an author but we should like to risk some very general comments this time because, if they seemed to you so far in point that you applied them to a revision of the ms., we should welcome a chance to reconsider its publication.”

These “very general comments” were based on one key observation: the story didn’t work toward any type of conclusion. The novel may well have been “true to life” but the typical reader was likely to be left disappointed by the experience. [3] His former school mentor and friend, Shane Leslie, whose poems were already being published by Scribners, shared his own thoughts about Scott’s book in a letter written to the publisher’s President, Charles Scribner II. Shane’s letter, written from the home of Alice Roosevelt Longworth in the Embassy district of Washington D.C, took little time in getting to the bones of the matter: “[the book] gives a vivid picture of the American generation hastening toward war … I marvel at its crudity and its cleverness.” Shane was enormously proud of his former pupil. In his estimation, the very ‘vivid’ picture the book drew of “modern youth” may have been “painful to the conventional” and in places a little “shocking”, but as a “boys book” Leslie thought it had the playful and irreverent poetry of an “American Rupert Brooke.” Even Scribners thought to reject it on the basis that it was a little naïve, he believed that the publisher might consider the impact that Fitzgerald’s witty and topical efforts might play as part of the ongoing war effort. Scott had enlisted in the US Army in October 1917 and it was Leslie’s opinion that a book like this — one that spoke directly to American Youth — would appeal to and give expression to the scores of volunteers (and non-volunteers) currently being targeted by the “super-patriots” of the American draft boards and their ideological-arm, the YMCA. If Scott was to die in battle like the poet Rupert Brooke, then the book’s “commercial value” would be even greater still. Leslie may have added the bit about Brooke in a fairly flippant, spur of the moment fashion, but from a business point of view, the point that he was making was a good one.

It wasn’t some idle outpouring of patriotism that had got Leslie thinking this way, it was his job. During the First World War news and propaganda work was often carried out overseas by men like Leslie who would usually report to the Directorate of Military Operations and Intelligence at the War Office. Born to a powerful American mother and an Anglo-Irish baronet, Leslie had been supporting British Ambassador Cecil Spring Rice in his bid to win the support of Irish-Americans in the pro-war effort in Washington D.C. The work he did would consist of promoting films, books or news items that furthered the aims of the war and kept the hearts and minds of the public firmly on the side of the allies. Whilst there is much uncertainty about his exact role, a letter written by Leslie to his aunt Jennie Churchill, offered some tantalising clues. Of his activities in the US he would say nothing more “except to say quite privately that I am not unemployed though you must not ask how.” In another letter he had warned his mother, Leonie Leslie not to write to the Foreign Office or discuss his activities with others. [4]

For their support, America had pinned its hopes on the Vatican, the moral barometer of the Irish Catholic voice, who had so far remained unwilling to offer unconditional backing to the war with Germany. Their secret weapon was Father Sigourney Fay — a friend of Scott and Leslie who had volunteered to go to Rome to grease the wheels of cooperation from within the vigorous molten core of the Holy See. Whether he was comfortable with it or not, Scott was a Catholic Irish-American, or in his words, “half black Irish” with a “two-cylinder inferiority complex.” [5] Leslie’s tactics may seem a little cynical and exploitative to us now, but like many men his age, his loyalties and obligations to his ideals, aspirations and friends would be forced to share space in his kit-bag with the more pragmatic demands of the nation. Leslie had been quick to recognise that Scott wasn’t just a fine and talented patriot, he was a fine and talented Irish-American patriot. There were opportunities here for everyone. Even Rome.

To ram the point home about his patriotism, Leslie had made a point to mention in the very first lines of the letter that Scott was a descendent of the composer of ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ and Benedict Arnold, the former hero of the American Revolution who for reasons best known to himself became a British Spy. [6] It was a smart if sneaky move. This wouldn’t just be any book, the book would form a critical part of turning vast numbers of American youths and bright young intellectuals who had so far remained indifferent — if not completely hostile — to the war with Germany, into ‘gallantly streaming’ martyrs eager to do ‘their bit’. What’s more, it was written by a boy with stellar (if slightly ambiguous) pedigree in patriotic matters.

That the brash and precocious author was only very distantly related to Francis Scott Key and not at all to Benedict Arnold, wasn’t touched on in Leslie’s letter. The only thing that mattered was that Scott was linked by blood to the American national anthem. The ‘Land of the Free’ and the ‘Home of the Brave’ was quite literally in the young boy’s genes. If there was any truth at all in Eugenics, then Scott was part of a gene pool in which patriotism swished around in the purest and most epic of ways. It was a predictable pitch in the circumstances. America had initially failed in its bid to raise an army of volunteers. After six weeks of furious campaigning only 73,000 men had enlisted, a relatively poor addition to the 100,000 men in its regular army. As a result, the Committee on Public Information had been forced to think more creatively. Investigative journalist George Creel had come up with an idea: the ‘Propagation of Faith’. The patriotic messages of America would differ to those of Germany. Unlike ‘the boche’ they would focus their efforts on circulating positive American values, and journals, books and newspapers would all be enlisted to extend their reach. Among the CPI’s greatest successes was Edith Wharton, a Paris-based writer whose 1918 book, The Marne (A Tale of War) had been finished in haste and rush-released by Scribners as part of the ‘push’. And if the positive messages failed, Liberty Bonds would be there to fill in the gaps — appeals to a person’s pockets generally faring better than those being made to the conscience. Scott would eventually meet Wharton at Scribner’s in 1923, and follow-up it up with a more cosy rendezvous in Paris a few years later when the Pulitzer prize-winner praised Scott for having taken such “great a leap” forward with Gatsby.

Leslie’s actions had been pretty astute. In the first years of the war, Scribner’s had done their best to maintain a neutral stance. Its magazine depended on subscribers to keep it viable, and a flurry of pro-English articles in the first twelve months of the war had led to a deeply worrying spate of cancellations from neutral and pro-German subscribers. Publishing Thoughts on War from the pen of British author, John Galsworthy had probably done little to preserve the peace. [7] By the time that America entered the war, the market had changed dramatically, bouncing aggressively from one end of the spectrum to the other. At first, the tone of commentary on the war in its monthly magazine was neither critical nor sensational. This had been fine for a while, but very soon the world of publishing was in crisis. Like many American publishing houses, Scribner’s relationship with other firms in the warring Allied and Axis Powers was bringing it to the point of collapse. By 1915 business was becoming absolutely wretched. Consumption had slowed considerably and there was increasing anxiety about the failure of global markets.

As the tide of opinion in America began to turn against Germany, Scribner’s Magazine brought in Princeton man Henry van Dyke, who had resigned his position as US Ambassador to Luxembourg and the Netherlands to lend the full weight of his experience to the country’s propaganda efforts. [8] A selection of his poems had already been featured in the Committee on Public Information’s Battle Line of Democracy, a collection of prose and poetry published as part of the ‘Red, White and Blue’ series in support of the Great War. [9] Two years later he would edit A Book of Princeton Verse II, which would feature, among others, a trio of debut contributions from the pen of 24 year old Princeton dropout, Scott Fitzgerald. [10]

In the end, Leslie did what anybody would have done in his position; he had looked around at the tools and resources he had at his disposal and made the most of them. To a creative, seasoned diplomat like Leslie, Scott presented something far more intoxicating than propaganda, he gave the people of Young America, a vision of Young America that was worth fighting toothcomb and nailfile for. The war lurched on and Scribner’s profits continued to tumble. It was just a case of convincing Scribner that they could capitalise on the young man’s talent both ideologically and commercially. Scott was indeed a rebel, but if handled and chaperoned correctly, he would be a rebel with a cause.

After making several major revisions, a new version of Scott’s book was duly accepted by editor Maxwell Perkins the following year. But it didn’t come without a fight. Scribner’s publishing executives still weren’t convinced. In the end, Max was left with little option but to tell his editor-in-chief that if he wasn’t prepared to publish work of this calibre then it was likely he would lose all interest in publishing books forever. The boy was talented, witty, charming, fantastic to look at in photos — what was not to like? [11]

An invite to London

On September 16, 1919 Max was delighted to tell Scott that Scribner’s were now “all for” publishing his book. Whilst essentially the same book, Max believed that Scott had transformed and extended the vision he had had originally. The book still sparkled with all the energy and life of his first drafts but it was more concise and better proportioned. Max said he was glad that Scott had not only persevered with the novel but also decided to sign with the very conservative Scribner. In all likelihood, the thought of an extraordinary talent like Scott falling into the hands of its Soviet-friendly rivals, Boni & Liveright, would have been all the encouragement that Scribner’s needed, especially at a time when America was genuinely very fearful of a gradual slide into Bolshevism. One thing that everyone at Scribner’s could agree on, was that they didn’t know how his book would sell because it was so manifestly different from anything else they’d published. It was a potpourri of poetry, letters and experimental fragments — a real prose libre. The left-leaning Horace Liveright would probably have given his right arm for it and many, not unfairly, thought it to have been Scott’s more natural literary home. But as someone whose messy, creative brain craved rules and discipline, he found Charles Scribner and his firm provided certainty and structure in what was often “too mutable a world.” The “tremendous squareness” that they possessed was a very definite plus. As his later writings attest, Scott had seen a very curious advantage in a “radical writer” being published by what had become an “ultra conservative house.” [12] His reward for persevering with Scribner? A royalty of 10% on the first 5,00 copies sold and 15% on the rest. [13]

On hearing of his good fortune his old friend Leslie scribbled off a message from his home in Ireland: “Dear Fitz, I am delighted to hear of your novel. If you stick to the style as well as matter you are bound to come on.” A follow-up letter the following summer joked about sending him a much deserved autographed copy and ribbed him about his spelling and his lightning fast literary success. His talented young protégé had come by his fame and fortune “at a stride.” Despite all his considerable efforts to get his book published, it is clear that Leslie was feeling no small amount of envy. Leslie had been writing for years and his name, even now, was embarrassingly obscure. If you were to read between the lines of the letter, the message was pretty clear: Scott had been using all of the sorcerer’s energy. In September 1920 Leslie was determined to remind him of the role that he had played in his success. Writing from his home in Bayswater, London, Leslie teased him by mentioning that publishing deal with Scribner had arisen largely because of his efforts: “The book was improved on the MSS [that] I persuaded Scribner to take and publish should you die like [Rupert] Brooke on the front.” Clearly anticipating trouble, Leslie had added a word or two of warning. He believed that ever since the death of their mutual friend, Monsignor Fay, it was up to him to ensure that Scott talents didn’t hurt anyone, including himself. His words had a sobering, biblical edge: men were only clever when they were “on the pry for forbidden fruit.” Leslie, obviously keen to retain a tight spiritual and moral grip of his young Catholic protégé duly extended another invitation: why didn’t he and Zelda head to London? If they did, they could go and visit their old friend Father William A. Hemmick in Paris, who was offering outreach and salvation to the colony of young Bohemians from the riotous Saturnalia of ex-pat joints in the Latin Quarter. [14] Leslie also had more to offer; if Scott needed material for another novel, then he had plenty from his own time in Paris that he was prepared to share. The trip to London was being planned not as some reunion of old friends, but as an opportunity for Scott to thank him for his stellar success.

Scott, however, was moving on quickly from Shane Leslie. Writing of Leslie in the New York Herald the following year, Scott had described how this charismatic ‘personage’ had totally transformed his life. The clouds and the fog had lifted, allowing the glamour and the romance of the church to circulate. At The Newman School for Boys, Scott’s Catholic prep-school in New Jersey, Leslie had come into his life “as the most Romantic figure” he had ever known. He had befriended the great Leo Tolstoy in Russia, he had gone swimming with Rupert Brooke. The most colourful and compelling anecdotes fell from his lips like little puffs of magic. He’d dined with kings and like his former hero, Shelley, he’d gone to Eton — the prep-school of kings in Berkshire. In the first months of 1920, Scott had still regarded his old friend as the dreamer of Old England weaving his liberal fantasies against the “shadowed tapestries of the past.” But Leslie’s influence — and his once fascinating Victorian ‘otherness’ — was becoming a burden. The past clung on to Leslie, and Leslie clung on to the past. In the old days he and the school’s visiting tutor and treasurer, Father Sigourney Fay, had made the “church a dazzling, golden thing.” Between them they had tried to persuade Scott that he could write “the great unwritten Catholic novel — the John Inglesant of the United States.” [15] For years, both men had invested no small amount of time in broadening the boy’s experience of culture, introducing him to all the legendary New York families like the Vanderbilts, the Astors, the Chanlers, the Roosevelts and Hearsts and refining his literary tastes. In those days, Scott had hung upon his every word and followed every scrap of advice. But things had changed.

The biggest thing to have changed was Scott’s wealth. If he needed ‘material’ from France, he now had the money and the confidence to harvest it for himself. But it wasn’t just cash that he had in abundance now, he also had some experience of living away from home. His relationship with Zelda, and his three short months in New York, had expanded his mind in a way he could never have dreamed of. Now he had all the filters in place to process the overwhelming mass of white noise that life presented and separate into channels what belonged to the past, and what belonged to the future. In short, the “low haunting melancholy” of a dying age that Leslie represented, was becoming no match for the catchier, razzle-dazzle tunes of Broadway. Visiting his old friend in London presented the ideal opportunity to show Leslie just how much he’d come on in his life and career. The jibes that Leslie made about his spelling and the liberties that Scott had taken in recycling other people’s letters and conversations would almost certainly have rankled his ego and Scott was probably keener than ever to show him what a literary force he’d become.

Leslie needed little encouragement when it came to taking credit not only for Scott’s success as a writer but also for his marriage. Fitz married on the resounding success of the novel I had carefully corrected. With Zelda he became the Apollo of the new Jazz world. They took the trouble to travel to Europe to thank me for my part in their triumph.” Blinded by years of privilege, lavish praise and excessive deference, Leslie was unable to appreciate the deeper motives behind the trip; the Trimalchio of New Jersey was going to break bread with his former master — and in doing so, correct any social and creative imbalances that might prevent the growth of their friendship. The ‘Apollo of the Jazz Age’ was coming to London, seeking liberty, equality and fraternity with his more advantaged cousins. Nevertheless, recognising the swift reversal in dynamics between them, Leslie had ended his letter: “I shall always be your admiring inferior, Shane Leslie.” [16]

Pacing the Floor at the Plaza

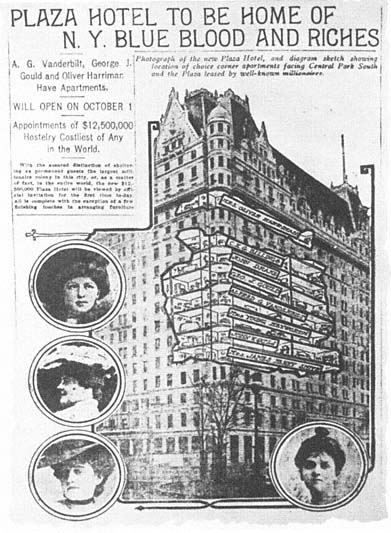

In 1919, Scott had earned just $879.00 from writing. By the time that he was leaving for England in May 1921 that figure had metastasised to a bewildering $26,500 — most of the money earned from short stories and magazine articles he’d scored off the back of the book’s success. The fee he picked from The Metropolitan magazine for a preview of his second novel was $6,300 alone. But the faster Scott became at earning the money, the faster he got at spending it. And he was quite honest about it too. In an article published in the Saturday Evening Post in April 1924, Scott shared an amusing and very candid account of his and Zelda’s rather cavalier approach to money. The article, How to Live on $36, 000 a Year gave readers a glimpse of his and Zelda’s life at that time. They had fully intended to try living on $18,000 of the $24,000 he had earned the previous year but the move to Great Neck had dealt the plan a hefty blow. Great Neck turned out to be party town, “specially built for those who have made money suddenly but have never had money before.” The L.I.R.R Express Service meant you could reach Broadway in just thirty minutes, making it popular with the riotous theatre crowd that included Follies dream-merchants Ed Wynn and Gene Buck, whose legendary parties Scott and Zelda attended. Elsewhere in the article, Scott confesses that for the first few years of their marriage their income averaged a little over $20,000. Money had been coming easier and easier with “less and less effort” and yet he was constantly surprising his wife with news that they were broke. Thinking that his day in the sun would last forever, the couple had been lavishing their income on expensive hotels, expensive cars, expensive parties and expensive friends. In October 1920 the couple had moved into a large condo-suite at The Plaza Hotel on West 59th Street — one of the classiest hotels in New York. The rates on the apartment were astronomical. And because neither of them cooked, every meal would be taken in the Plaza Grill Room below. The price of being famous meant having bigger holes in his pockets for even bigger diamonds to fall through. Zelda would later joke that they had gone to the theatre so much during this period that Scott was taking it off as income tax. [1] For someone who had been struggling to earn more than a few hundred dollars a month the winter before, it was the ultimate experience in lavish and careless living. The article, for which he received a respectable $900, was published as Scott was about to set sail on his second trip to Europe to start work on his new novel, The Great Gatsby. [18] One thing’s for certain: the extravagances described by Scott in his own life certainly chimed with the excesses of the parties laid on by Jay Gatsby in West Egg.

The $26,000 that he took in earnings that year couldn’t have all been blown on living expenses, so what exactly was he spending it on? During his first year of success Scott had earned $17,000 and paid just $1, 444 in tax. The following year would have placed him among the top 1% of American taxpayers. By modern standards, the 5.5 effective rate had made it practically tax-free. Anybody looking for an explanation for the couple’s habit of being broke are confronted with images not unlike those at Gatsby’s lavish parties: the constant toing and froing of guests at their Plaza Suite, the hiring of Rolly Royces as buses, huge crates of oranges and lemons arriving by the truckload, and a corps of caterers marching operatically through its halls as a five-piece orchestra strikes up the latest Gershwin tune. The money had to have gone on something. He certainly had the same appetite to impress as Gatsby, so it’s possible he had the same spending habits too.

Just five months before his trip to Europe in December 1920, Scott was telling his editor, Max Perkins that his bank was refusing to lend him anything on the security of stock he held and that he had been “pacing the floor” all day deciding what to do. He was within weeks of completing his second novel and had “six hundred dollars’ owing. To make matters worse he also owned $650 for an advance on a story that he “utterly unable to write.” His debts to Scribner’s were no better. Either way, that didn’t stop him asking for another loan: “could you make it a month’s loan from Scribner & Co. with my next ten books as security? I need $1600.00.” [19] By March 1921, the couple were left with very little option but to move out of the Plaza Hotel and back to the home of Zelda’s parents in Alabama. The dreamworld that Scott had been building was falling apart. During the course of their courtship the pair had exchanged a series of letters in which they had contemplated the dazzling New York ‘fairy tale’ that that stretched out blithely before them like some dollar-lined yellow brick road. In her semi-autobiographical novel, Save Me the Waltz, Zelda would write that it was a “city of glittering hypotheses”. Everybody from home would seem to drift there eventually, usually arriving at some insurance or advertising company, a menial job in the office being the deal you struck with the devil for convincing everyone back home that you were livin’ la vida loca. Scott’s fictional alter-ego in the book, David Knight, would describe the city of New York as like “chaff from a fairy mill — suspended in penetrating blue.” The tops of the buildings on the Manhattan skyline shone like “crowns of gold-leaf kings in conference.” To someone who felt that he had muscled his inadequate little boat into the middle of the Hudson River on sheer force of will alone, the view was something special. Scott had attended the millionaire parties and the back-slapping Yale-Princeton reunions but they had all left him feeling empty. He was looking for another ladder to climb and this is where he found it. Just as in Gatsby, the irregular tiered blocks rose up like “sugar lumps” against the of the midnight belt of the city in dazzling “white heaps”.

Open to Persuasion

After being demobilised from the army in February 1919, Scott had bagged a job as copywriter at the Barron Collier advertising agency in New York. The agency, Street Railways Advertising was based in the 24 storey Candler Building at 220 West 42nd Street and specialised in streetcar (tram) advertising. Plastered over the battered interiors of practically every street car in North America was a perky and persuasive ‘car card’ by the Collier company pushing everything from soap powder to war bonds. A promo card from the agency read “People read Car Cards and profit by the buying suggestions they contain — just as you are doing now.” America was now open to the power of suggestion. It really didn’t matter whether it was cigarettes or salad dressing, one way or another you were sold a dream that you didn’t even know you’d been having.

The agency was run by Barron Gift Collier, a neighbour of John D. Rockefeller, close friend of Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson and the owner of the dazzling and other worldly pleasure park, Luna Park, one of two massive theme parks that dominated Coney Island in the first years of the Twentieth Century. It’s even brighter rival was ‘Dreamland’, that sprawling oasis of desire bankrolled by the legendary gangster, Arnold Rothstein. Between them Collier and Rothstein had given birth to basic doctrine of Modern Consumerism; people were no longer just buying things to satisfy essential needs, but to satisfy other kinds of longings, longings that could also be stimulated. The image of the rickety old Ferris wheel encapsulated the whole thing beautifully: it had no bottom, it had no top and it went around in an infinite circle — a journey without any real chance or any real desire for arrival. It was safe, contained environment for subversion to take place: “licensed freedom away from the workplace”. For several hours in the evening the weary, pent-up frustrations of the masses could be unleashed within the park — and those who owned the park could transform all that pent-up misery into profit. One thing it did offer though was hope. For the millions of young immigrants who streamed through its gates every month, it had been the beacon that had brought them all to safety and promised them full and lasting redemption. It was here that everything twinkled like a star. And at just five cents a trip on the railroad, practically anyone could get involved. Express trains would leave Brooklyn Bridge at 7.30pm and arrive shortly after 8.00, the elevated rides speeding up access dramatically. People would turn up at their gates with a “simplicity of heart” that was almost, but not quite, “its own ticket of admission”.

When America entered the war in April 1917 and was raising funds for Liberty Bonds, Scott’s boss offered to advertise the loans for free. Collier followed this up with the production of a ‘patriotic series’ of cartoons as part of the aggressive propaganda efforts being mounted under Wilson. By 1919 Collier was one of New York’s leading advocates for the League of Nations and was instrumental in founding Interpol, the International World Police Organization. His war efforts were rewarded in 1922 when he was put charge of the Bureau of Public Safety after being appointed Special Deputy Police Commissioner of New York by Police Chief, Richard Enright.

Shortly before his death in 1940, Scott would write to his daughter Scottie reflecting on his time at Collier: “Advertising is a racket, like the movies and the brokerage business. You cannot be honest without admitting that its constructive contribution to humanity is exactly minus zero. It is simply a means of making dubious promises to a credulous public.” But whilst he accepted just how disingenuous the whole business was, he also recognized that his life may have taken a totally different turn had he been promoted during his four short months there. Principles and pride were one thing but sometimes there were more overwhelming needs to consider. With more money he would have been able to marry Zelda. He wouldn’t have needed to become a writer. In short, his life might have been very different.

During the few short months Scott had spent riffing on jingles and slogans at the Barron Collier advertising agency he’d been scouting out his empire. A change was taking place. Among the taxis and gathering rain Scott would see himself as a young Dick Whittington marvelling up the iridescent signs of Broadway and that neo-Gothic cathedral of retail power that was the 800 foot Woolworth Building. In a revealing retrospective of his time in New York written for Cosmopolitan in July 1932, Scott recalled the “nourishing” spirit of the Metropolis whose magic would transform the “shy little scholar” into the swaggering man of the world. Everywhere he looked were theatres, the playing cards of fortune in a never-ending game of dreams. At the back of the agency building was the Sam H. Harris Theatre, leased to them by Coca Cola magnate, Asa Calder. Four years later Scott would work with Harris on his play The Vegetable. Mesmerized by the stunning visual cabaret of the metropolis he would leap from street to boulevard, mapping out his future on a mood-board of epic proportions, stopping only to feel the crackling pulse of electricity throbbing beneath his feet.

It was during his time at the agency that Scott had been feeling that he had no more control over his destiny “than a convict over the cut of his clothes.” From the spring till the start of summer he was flat out broke. He would have loved to get an apartment in Greenwich Village but the price of rent in Washington Square, regarded by many as the free and independent Republic of Bohemia, had shattered all hope of living a ‘mellow monastic existence’ among the wordy, libidinous and fabulously magnetic crowd that gathered at Edmund Wilson’s West Street 12th apartment. At the one property he could afford the landlady had put him off when she said that he was free to back girls at whatever time he pleased. The whole idea had depressed him greatly. He had a girl. He had Zelda. As fun as it was to observe and enjoy the lax moral standards going at Wilson’s place, Scott had found himself repulsed by the woman’s failure to offer a room that could match the scale and the purity of his dreams. He was content to attend the parties, but experienced no real impulse to join in. As in Paris he had come only to stare at the show, an appreciative observer of inhibitions being lost and the thrill of licentious behaviour. When he returned to New York a roaring literary success some six months later, these experiences in remote viewing remained. The only difference was that he was no longer a detached observer but an “archetype” of what New York had wanted all along. It was like he fulfilling some national prophecy. Not for the first time in his life it had it all begun to feel like a performance.

In the manuscript draft of his first novel, This Side of Paradise, Scott had written that although he had “lived so much” he had never really lived it from within himself. They had been lived within “mirrors” of himself that he had found in other people. He had never really looked upon himself as a mortal and would always strive awkwardly toward some unimaginable “higher purpose.” Scott, by his own admission, was constantly on the lookout for something that would absorb into him the eternal. The “world of the picture actor” was like his own — he was in New York but not of it. Eventually he would put some of these feelings into the mouth of Nick Carraway, the dislocated narrator of his third novel, The Great Gatsby: “I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.” Scott was begging to feel like he had no real centre, as such. He was a virtual-reality man living in virtual-reality city, a series of successful images projected upon a screen. Contrary to all expectations, Prometheus had found himself slumming it with mortals in the liquor joints of New York. [20]

In those first weeks after leaving the army, Scott had taken an $80 dollar-a-month apartment on Claremont Avenue in Morningside Heights just two blocks away from the Hudson River. Across the bay he could see the wrought-iron skeleton of the Palisades Amusement Park, the symbolic threshold to another world. The Ferris Wheel, which at night would explode like a aurora on the New Jersey skyline, was by day just a mathematical roulette of cold, metal rods and curves, but it was here that the magic happened. By 10.00pm it would be a beacon, big and bold compelling enough to arouse curiosity and trigger an exodus to its gates. The voltage being pumped into the park at night would have been immense and Scott might well have sat in his apartment, downing one shot of Bushmill’s whiskey after another, getting high on the very hum of electricity pumping through its grounds. There was energy in what he saw, a charge. The apartment and the district immediately south of it would later feature his second novel The Beautiful and the Damned and The Great Gatsby, where it was repurposed in the latter as Tom and Mrytle’s love nest. It wasn’t a dive, by any means. The apartment blocks of Morningside Heights, which were used by and large by the students of Columbia University, were often advertised as ‘high class’ and references were required for applications. The building even had its own mail chute. In the cool summer evenings young girls would make their way to the corner of the street to pick-up ice-cream sodas from the drug store, “dreaming unlimited dreams” as a man on a hand-organ or hurdy-gurdy would crank out a tune. [21] Here he would allow the music and the smell of the perfumes wafting up from the drug-stores below to transform his $80 one room apartment into a Plaza Royal Suite.

When he visited his friend Wilson’s Village apartment, it was like taking the elevator down a few floors into hell, the ‘anything goes’ hedonism of the experience jamming the circuits of Scott’s more instinctive midwestern Conservatism. The only credible option in such circumstances was to get well and truly stewed. The vision of his and Zelda’s future that he had in his head was composed of neat lines and firm borders, totally at odds with the messy improvision of Greenwich Village lifestyles. A few shots of illegal liquor was often enough to loosen the edges and make it all fit somehow. In October 1922, a review of the riotous, bohemian antics taking place in The Village would appear in Harper’s Bazar. Supporting the review was a satirical ‘graphic survey’ by Reginald Marsh of the Art Students’ League. In the slightly surreal cartoon landscape created by Marsh one was invited to pick out many of its famous radicals staring out of windows and falling out of bookshops as a truckload of ‘Young Intellectuals’ tore through Seventh Avenue on their way to a picnic. Among the figures depicted in the truck were Scott Fitzgerald and his friends John Dos Passos, Edmund Wilson and John Peale Bishop. The two panel piece also showed Scott and Zelda diving into a public fountain. But the picture didn’t tell the whole story. Not where Scott was concerned. Not where Scott was concerned, anyway. Years later the author would write that neither the millionaire parties nor the ‘moony cabaret’ antics in the village satisfied him in any meaningful way. They were “impressive scenery” but they didn’t stop him getting “weeping drunk” every time that he got home. Whenever the feral conditions of bohemian idleness that Wilson’s friends set for him got too much, he would be seized by the urge to get out and walk south towards Wall Street and Union Square, scene of so much change in America’s history, but like a flip-flopping Nick Carraway he would be pulled back by the ropes of argument and counter-argument back across the hot glowing coals of The Village. As keen to fit in as he was, he was a guest there, a nervous invite. Even when he assumed the mantel of the city’s spokesman for his generation, he had no qualms in admitting that he knew nothing about New York. All he really knew for sure was that there was much loneliness there as here was glamour and that for every one of its heroes there was a tragedy just waiting to happen. [22]

Over time, Scott’s slightly awkward and always drunken affair with Babylon had given him time to think. Don Dickerman’s Pirate’s Den on Christopher Street with its patch-eyed waiters and jolly roger flags had enchanted him at first, but it was a tourist affair at heart and already on the decline. During Easter 1920 the den and its adjacent streets were invaded by canvassing church workers keen to understand the inner workings of its unholy heart. The studio of the struggling artist, the mysterious habitat of vers libre was about to have it heavy doors shaken and its decks scrubbed. In all fairness, Scott would probably have felt more at home in the speakeasy’s haunted stable alleyway where the Gay Street Phantom was said to roam. For the next twelve months Scott would be punching in the coordinates for a bigger and brighter future. The more desperate his circumstances became, the more strength he derived from having almost nothing at all. After he signed his deal with Scribners, the footprints that had once seemed so light had begun making deeper impressions. As he shuffled around its avenues the sound of its clanking horns diminuendoed into oboes and clarinets in a dreamy, hypnotic wave of city romance. The giddy waltzing patrons of the Club de Vingt, high on celestial liquor, would spill in their hundreds onto Madison Avenue with all the jeering torment of evil spirits. For a time they had only served to remind him of just how very he was from the lavish realm of success he’d pinned his hopes on. Now they were his friends. Occasionally he had hid behind the high wall of books at Wilson’s Village apartment, and for a time, this had been his sanctuary. Every day he would wait for the letter that would reassure him of his fortune, and every day that letter didn’t come. Alcohol has anaesthetized him from crueller blows of the city but Scott remained haunted by the comforts of his easy, Midwestern ways. Occasionally he would pick up same-day discount theatre tickets at Gray’s drug store on the corner of Broadway and 43rd Street, charmed into submission by the fast talking salesmen in the box office. At other times he would stare blankly at the religious books bought for him by his mother or watch the drunken musicians making a balls-up of some dance at the Knickerbocker Hotel at the southeastern corner of Broadway. But gradually, as the money came in, the ghost that he had felt as a lowly-paid slogan writer was acquiring some flesh. New York was a city that he was both created by and creating. It was an isle that was full of noises. Its wild, dissolute energy raced like heroin in his veins and then spilled to the floor around him. The Great Fitzgerald had arrived in West Egg. He had everything he wanted and knew instinctively that from that moment on he would never be happy again. [23]

A Failing Fantasy

For many in the trade Scott’s debut novel had been “the startler of the year.” The youth of America were waking up and for the first time in generations, American Literature felt like it was really making progress. Some thought the novel greatly over-rated. Others, like Heywood Broun and Scott’s former tutors at Princeton, questioned the authenticity of the “atmosphere” he had created. Were the Ivy League students really behaving like they were in the book? [24] For many though it was a novel that presented the “true adventures of youth.” By his own admission Scott had been pushed into the position of “spokesman for his time”. Despite this, he also knew that he was a “typical product of that same moment.” [25] New Historicists like Stephen Greenblatt would probably try to argue that Scott was both a reflection of his time and a significant intervention within it. Today we talk of artists capturing the zeitgeist, usually confining it to the way that a writer defines the spirit or mood of a period. But Scott was probably guilty of something a little more complex. It was one the most remarkable instances of self-fashioning in literature: the model to which he aspired didn’t really exist outside of Scott’s imagination. The ‘flapper’ and the life of the flapper was something he had extrapolated from socially ambiguous region in which he and so many others stood back and observed. An expression of anxiety became an expression of rebelliousness. Scott hadn’t even used the word in his word novel but by the time that The Beautiful and the Damned was published, he was claiming the whole flapper movement for himself. Lesser writers were often just happy to reflect the world in which they lived. The best ones transformed them. Scott’s astute sense of business had spotted that there was not only money to made from the phrase, but a small place in history too.

He and Zelda were under absolutely no illusion that they were a cause of and a cause perpetuating their own gorgeously indulgent existence. New York knew what it expected of the couple, even if the couple weren’t entirely sure what they expected of New York. All that they knew for sure was that they had been busking the entire experience and were bouncing along Fifth Avenue with their hats filled with gold — fool’s gold. They’d enjoyed frolics in public fountains and had various brushes with the law, and for whatever reason they seemed untouchable. The “tall white city” that Scott would speak of in his later essay about the period had adopted them as its Electryone and Apollo. In this world of his own making the couple were able to combine all the miscellaneous scraps of not-belonging and not-behaving into a super-charged idea. As Scott explained, the “younger generation” movement he had come to represent had become “a fusion of so many elements in New York life.” But despite his command of the idea he had of New York in his head he actually knew less of the real-life city than a “hall-room boy” at the Ritz. Before either of them knew it, they had been pushed into being not only “products” of that moment, but spokesmen for it. Like they were meeting on Long Island, they found that they had ‘roles’ they couldn’t fulfil. The tornedo that had ripped through their lives had left them stranded in a world that had “little sense of itself and no centre.” The “unreality of reality” that would write about in Gatsby was becoming less and less appealing, and less and less easy to maintain. Fearing that any at any moment he might be rumbled, Scott had found himself scouting out a possible escape route.

Any thoughts of escape though were, however, complicated by the demands of earning a living and the sticky, possessive machinery of success. For over a year the pair had been protected for no good reason by an impenetrable wall of glamour. New York had proved to be the cynical and heartless city that provided a broad, golden band around the crown of the Jazz Age duo. Anybody would have thought he found exile on another planet. For the moment, at least, Scott had wed his “inutterable visions “to the “perishable breath” of the city and the girls of his dreams. [26] Long before they were married, Scott would write to Zelda with a simple sketch of his dreams: “You are my princess and I’d like to keep you shut forever in an ivory tower for my private delectation.” [27] For the most part, Zelda would write back, offering words of reassurance that would support his romantic vision: “our fairy tale is almost ended, and we’re going to marry and live happily ever afterward just like the princess in her tower.” But on other occasions it is clear that she would grow tired of his sentimentality and tell him to stop. [28] Like his later creation Jay Gatsby, Scott had been adding the “patterns of his fancies” with reckless sums of money. “The universe of ineffable gaudiness that had spun itself out of his brain” was fast unravelling and the ‘happy ever after’ that both believed had been their due was looking increasingly in crisis. The mind that had once “romped around like God” was in danger of becoming mortal. No amount of money ever seemed to be enough. The more money Scott earned, the more money he craved, and the more he craved it, the further it shrank from his grasp. In his third and most famous novel, Scott would write that it was when curiosity in Gatsby was at its peak that his brilliant, fragile world began to collapse. His career as Trimalchio was all but over. [29] The cocky former slave who had become an overly extravagant master had found himself slave to his own destructive fancies. But Scott was there ahead of him.

With one fantasy collapsing, the only credible option that remained was to leap into another one. What was left of the money had been saved for a trip to Europe — the one escape route from a world they now suspected of being unreal. Unlike New York, London, Paris and Rome would all have a very strong sense of themselves and real centres. But that didn’t mean it was going to be easy. Scott’s only contact with Europe had been through books. In his mind’s eye the streets of Paris, London and Rome were lined with philosophers, painters, architects, poets and Thirteenth century monks. The air would be purring with the warm, dreamy whirr of sonnets. Stucco reliefs and frescoes would be peeling in fine, powdery clouds of brilliant colour from the walls of every home. He dreamed of “moonlight excursions” in cities that were as old as the renaissance, gliding down alleyways of gorgeous “incandescence”. In his semi-autobiographical novel, The Beautiful and the Damned, which he completed after visiting Europe, Scott would describe how whole place had become some kind of “talisman”. The cities he would visit would be a place were “the intolerable anxieties of life would fall away like an old garment.” After pouring his lifetime of experiences into two breathlessly energetic novels, he was feeling spent. Europe would be place of restoration — renewal. Among their “bright and colourful crowds they would be able to forget the “grey appendages of despair.” [30]

There was another reason too: like so many Americans during the war Scott had suffered the indignity of not seeing active duty abroad. To make matters worse, many of his closest friends at Princeton had. Edmund Wilson had gone to France where he had served first with Base Hospital 36 in Vittel, before being transferred to the Intelligence Unit at General Headquarters in Chaumont, a fabulously atmospheric medieval city that sat terrifyingly close to the Swiss and German borders. John Peale Bishop, who had been immortalised as ‘Thomas Parke D’Invilliers’ in This Side of Paradise, had been more chivalrous still, running around France with his bayonet fixed and flashing with the 84th Division, known rather fabulously as the ‘Railsplitters’ after the legendary militia company captained by Abraham Lincoln. Years later, Scott would tell his friend, John O’Hara of a lifelong “two-cylinder inferiority complex”, saying that if even if he had been elected King of Scotland after graduating from Eton and could trace his lineage to the Plantagenets, he would still be an impostor, a “parvenu”. [31] Being innocently yet still rather fraudulently presented as “an American Rupert Brooke” by Shane Leslie would have done little to improve his self-worth. Not only had he failed to die tragically in battle, he had not seen one day of action in the two years he had been enlisted. Scott had dropped out of Princeton and spent the duration of the war at Camp Sheridan in Alabama — an “easy commission and a soft berth” — serving as aide de camp to Major James A. Ryan. In the end, his debut novel had all but glossed over America’s two year war with Germany in a rather dismissive and very self-conscious ten lines: his “total reaction” to the war was what his attitude might have been to an “amusing melodrama”. He had “hoped it would be long and bloody.” [32]

On the one hand a trip to Europe would level him up in the eyes of his peers, and on the other it would allow him to throw the veil of unreality back over the sharp, angry edges of already-spent earnings and old debts, and give him a whole new shot at redemption. Scott had wriggled free of poverty, the cold, bleak perma-frost of Minnesota winters and the even bleaker perma-frost of being an embarrassingly consistent Ivy League flop. His money had been doubling every month, but that had done nothing to increase his standing among the millionaires riding up and down Fifth Avenue. His default setting was to be “over-awed” by the always raising bars of ‘social position.’ Belonging to the “snootiest clubs” at Princeton had not eased his self-loathing. If anything it had compounded it. [33] His scholarship ticket might as well have been won in a card game. The time on the clock was ticking and the money was running out.

Time runs out at The Plaza

Things were changing fast in New York. Within just a few weeks of the couple grabbing their belongings and taking-up a noisy residence at The Plaza, an article in the New York Herald had cast a critical eye over the future of Fifth Avenue. Albert Ashworth, the New York City broker who had who had helped turn a handsome French Gothic building at the northeastern corner of Fifty-Second Avenue into the uptown base of the Empire Trust Company, was anxious about its future. Fifth Avenue, as he saw it, was in an inevitable state of decline. The “genuine old New York families” were quite being literally being driven off by ‘new money’ arrivals like Scott. Everyone who had made money suddenly seemed to want to settle on Fifth Avenue. The result had been that “the old families with old New York blood running in their veins” were taking up refuge in the more modest sections of Park Avenue. Luxury apartment complexes like those above The Plaza were taking over. [34] Scott could have spent his entire life in the Royal Suite at The Plaza Hotel but he would never have been one of their own. He and Zelda were members of the “newly rich” and any money they had was geared to be kept in constant circulation. Even the Long Island town the couple moved to the following year had been built to maintain this cheerful yet mandatory economic cycle. Scott had described Great Neck as “one of those little towns springing up on all sides of New York” that had been crazily purpose-built for those who had “made money suddenly” but had not had money before. [35] It was like an upscaled Coney Island — no less gaudy, no less exhausting, no less thrilling — and no more ‘real’. You went there with a “simplicity of heart” and after that you were immediately and quite rightfully absorbed into its capital-draining mechanisms with all the misery and fatigue of a dying battery. [36]