“Percy couldn’t have been at the Mutiny in Etaples because that month he was on the troopship, Orontes heading to India with his regiment”. Or so the story goes. It was used to undermine the whole pretext of John Fairley and William Allison’s book, The Monocled Mutineer and it’s been repeated by journalists ever since. ‘There’s no evidence to support that he was anywhere near the camp at the time of the mutiny”.

But there is.

In his book, Detective & Secret Service Days (1929), Edwin T Woodhall describes how he was transferred from Intelligence Police to Military Police at Etaples in an effort to restore order in the immediate aftermath of the ‘riots’. Starting his days in London’s Metropolitan Police Force, Woodhall eventually became attached to the CID at Scotland Yard before a swift transition to the Special Political Department, the Secret Service Department and the Special Central Department. By trade he was a spycatcher, a specialist in Counter-Subversion. Upon his arrival in Etaples in September 1917, he was tasked with rounding up the ‘Sanctuary’ deserters who had organized themselves into group around the wells, woods and tunnels of Camiers, and who formed a boisterous rear-guard to the Scottish and New Zealand soldiers barring the bridges with machine-guns. And it was here that Woodhall encountered one ‘singularly ferocious character’. His name was Percy Toplis.

If Percy was on the Orontes (often misspelled Orantes) heading to England at this time, then how could Woodhall encounter Toplis in the camps around Camiers during this very same period (October 1917)? And there’s another mystery to clear up too. According to Dennis Brook’s history of RMS Orontes, Occasional Troopship of the Great War the liner appears to have been handed back to the Australians by the British Admiralty in August 1917. It remained in the war effort, yes, but no longer as a troopship but as a merchant vessel transport dairy goods between the UK and Australia. Unless Toplis was masquerading an Australian dairy trader, it was hard to see how he could have been on that same boat heading to India.

Who are we to believe?

The Source of Confusion

The source of the problem lies with the handling of Percy’s war record by Detective James Lock Cox of Andover Police. Writing to the Chief Constable of the Andover Division of Hampshire Police Constabulary on 17th May 1920, Cox states:

“On the outbreak of War he joined up in the RA.M.C and a lady at Shipton Bellinger started a school to teach soldiers French. Topliss being one of the pupils. He was then stationed at Park House Camp. Topliss went to the Dardanelles in 1915 with a Field Ambulance Company, and it appears he was either invalided or wounded and sent home to the Depot at Aldershot From there he went on Trooping duty to Salonika, Egypt and back to the Depot and then to India in the Troopship ‘Orontes’. After a few months to Bombay from there to Egypt and it is supposed that in August or September 1918, he was missing and the next that was heard of him was at Nottingham.”

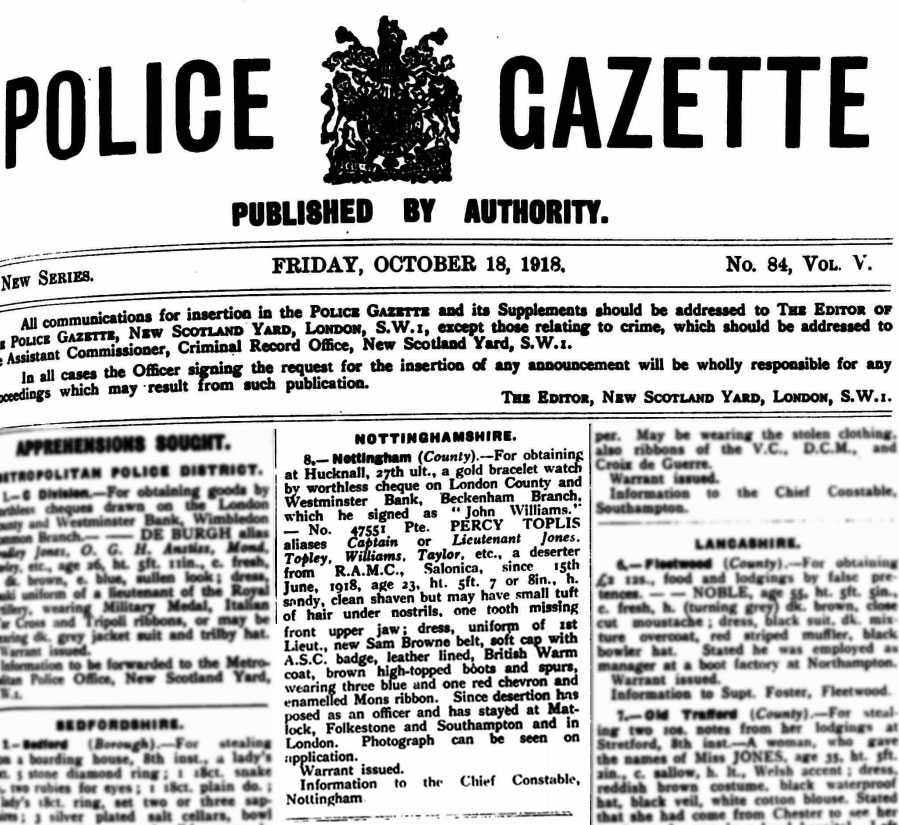

Contrary to what you’d expect, the sequence of events described by Detective Cox is not in chronological order. We know this because a report relating to a warrant for his arrest published by the Police Gazette on October 18th 1918, states that Toplis deserted the Royal Army Medical Corps from Salonika on June 15th 1918. His biography at Penrith Museum reads, “September 1917 saw him seconded to the troop-ship Orantes, en-route for India. He remained in Bombay for several months.”

Based on the report in the Police Gazette, Toplis was in Salonika and not Bombay during the early part of 1918. The date of his desertion was repeated at his trial by the judge who remarks that since the military had made no bid to ‘claim’ him, he would complete a custodial sentence of six-months hard labour. As the Police Gazette published a detailed monthly tally of deserters and absentees provided to them by the Ministry of Defence, there is every reason to believe that the date of his desertion and the location of his desertion are correct (Police Gazette, Friday 18 October 1918, p.1). His desertion also coincided with the trial of 16 conscientious objectors enlisted in the Field Ambulances in Salonika in June 1918 (they objected to being forced to renege on their objections – see the case of Wilfred Knott: The Opposition to the Great War in Wales 1914-1918, Aled Eirug)

The museum’s claim that Percy deserted from the RAMC at Blackpool, “shortly after the death of his father in August 1918” is wrong, quite simply. As the Police and press records show, Percy deserts from Salonika in June 1918 and is arrested by Police in Clerkenwell in London, sometime in October.

As members of the RAMC were regularly being transferred from one place to another, and often being seconded either permanently or temporarily to other field companies, it is entirely possible that Percy could have been in France in the last few months of 1917. The service records of Alexander Allen of Cowdenbeath in Fife reveal that this soldier was loaned by the 39th Field Ambulance (regarded by many to be Percy’s unit) to the 41st Ambulance train in France in early September 1917.

Is Woodhall a Reliable Source?

There’s little reason to doubt the account by Woodhall. Jarrolds of London was a reputable publisher with dozens of respected authors. John Gilbert Bohun Lynch, celebrated journalist and biographer of essayist, Max Beerbohm wrote for them, as did Sir Henry Lytton, Donald Featherstone (editor of the War Game Digest), Mi6 officers Henry Landau, Baroness Carla Jenssen (society girl and former spy), J. C.Lawson and Marthe Cnockaert (Belgian spy recognised for her work by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig and whose 2-page foreword was written by Winston Churchill) They were also the first to publish Black Beauty.

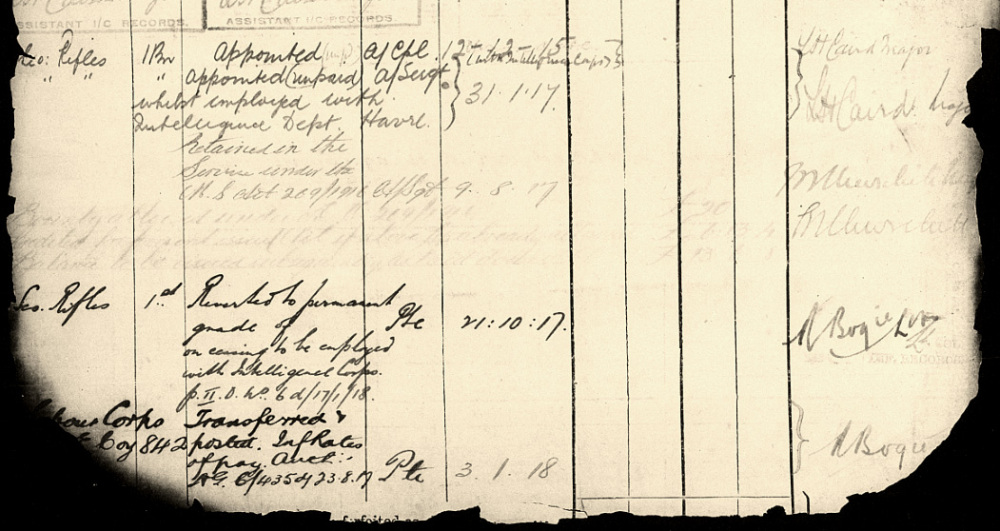

What reason do we have to dismiss Woodhall’s first-hand encounter with Percy Toplis, a man who had faded from the news some ten years before? The detective’s military records back-up his claims that Woodhall was enlisted into the 1st Scottish Rifles (Cameronians) in August 1914, transferred to the Military Intelligence Corps before eventually being seconded to the Military Foot Police during the period in which the army was rounding-up deserters in and around Etaples (he was also recalled to handle recruitment at the War Office in July 1939).

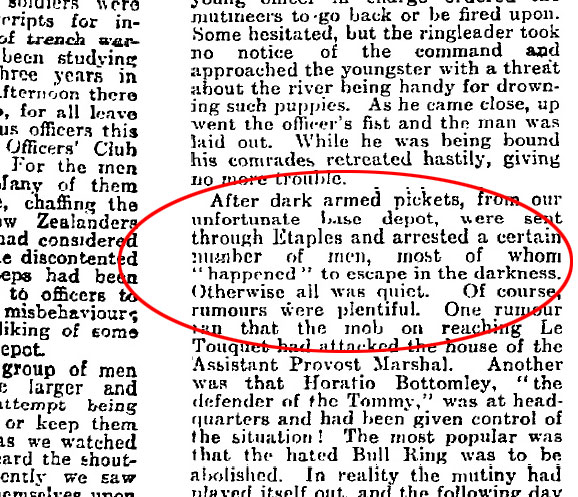

Woodhall’s account also seems to have rekindled interest in the Mutiny because within weeks of its publication the Manchester Guardian printed what appears to be the first press account of the Etaples Mutiny: The Mutiny at Etaples: An Incident of 1917 Fighting Soldiers and Red Caps (The Manchester Guardian, 1901-1959; Feb 13, 1930)

Intriguingly, the Guardian report appears to support Woodhall’s claim that some of the men were captured but escaped back into the darkness.

The War Chapters of Woodhall’s book can be read in full at the links below (two PDF documents). The chapter on Toplis is Chapter III, ‘Military Ishmaels’ (page 143). It is, however, worth reading in full to understand the full scope of Woodhall’s concerns about Toplis (the chapter on ‘Peter the Painter’ and the ‘Jules Bonnot’ Motor Bandits is especially revealing). Whether or not Toplis was a ‘ringleader’ is another matter.

other titles by Woodhall

Spies of the Great War (Adventures with the Allied Secret Service) – 1935

Woodhall’s second book, Spies of the Great War was serialised in Al-Ahram, an Egyptian broadsheet. You can read an account of the serialisation by Professor Yunan Labib Rizk:

http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/Archive/2003/633/chrncls.htm

Secrets of Scotland Yard (John Lane, 1936)

Guardian of the Great (Blanford Press, 1934)

Military and Police Timeline

1885: Born to carpenter and joiner, George Woodhall (b.1852) and Fanny Woodhall (1847) at 4 Oakleigh Road (now 4 Oakleigh Road North). The house was just yards from a Secret Service safe house (17 Oakleigh Park North) and the Soviet’s TASS listening post at 13 Oakleigh Park North.

1901: Lodges with his sister Fanny Saunders (b.1876) and brother-in-law Albert Saunders, Police Sargeant with the Metropolitan Police in Southwark, London (b. 1875). In the 1911 census Albert Saunders is listed as Inspector at the Metropolitan Police. Saunders eventually becomes Chief Inspector at 1st Division, policing the naval and military bases at Woolwich and Royal Arsenal.

1904: Enlists aged 19 with the Scottish Rifles reserves (no.8559). Stationed at King Street Barracks, Aberdeen. Excels in sports team. Brings him into contact with Aberdeen City Police Sports team.

1906: Marries Isabella Jane Paterson (born St Nicholas Aberdeen to Marine Stoker, Alexander and his wife Jessie)

1907: Joins Metropolitan Police – ‘V Division’ (Putney, Battersea and Richmond).

1911: Appears on the 1911 Census at 24 Ponsonby Terrace, Pimlico in Westminster, London. His occupation is recorded as Detective at ‘Special or Political Branch, CID, New Scotland Yard.

1914: Enlists with 1st Scottish Rifles (Cameronians) at Hamilton

1916: Transferred to Military Intelligence.

1917 September: Military Records show Woodhall seconded to Military Foot Police from Military Intelligence

1919: Discharged at the end of February 1919. An entry in the Metropolitan Police records reads that Edwin Thomas Woodhall (warrant number 94985) leaves the Police in July 1919. Last posted to P Division as a PC. This may be a procedural detail as Woodhall claims that he is enlisted into the Secret Service on being discharged from the army. Wahetever the case his discharge coincided with one of the largest Police Strikes of the 20th Century. The press were reporting that the Bolshevik Revolution had arrived in Britain. Was he put back on the beat as a result of these strikes? And did this have any impact on his decision to quit?

1924: First article appears in the The Weekly Telegraph: “A Day in the Life of a police Constable, late of V Division and CID, Metropolitan Police.

1929: First book DETECTIVE AND SECRET SERVICE DAYS published by Jarrolds of London

Woodhall’s army service records can be viewed in full at the National Arvives (Wo 363 – First World War Service Records ‘Burnt Documents’) and Findmypast.co.uk (Edward T. Woodhall, born Fincheley Middlesex, 1885, service number: 8559).

other posts in the series:

The Curious Case of Victor Grayson and the Etaples Mutiny

James Cullen: The Scottish Mutineer

Tinker, Tailor, Toplis … Spy?: The Enchanting Secret Behind the Etaples Mutiny