In a twist as bizarre as any in the story, it appears that the man Toplis was accused of murdering in April 1920, Andover taxi-driver Sidney George Spicer, had killed a man himself just three years previously.

The ‘accident’ with ‘fatal consequences’ occurred near Bulford Camp. What makes it all the more peculiar is that Spicer was accompanied by two-men, neither of whom appear to have been customers in his cab. One of the men was an Australian Soldier stationed at Sling (the Anzac base at Bulford). It appears that Spicer’s reckless driving had resulted in brewer’s drayman, Richard Charles Blake being thrown from his wagon. According to eyewitness, Gordon Macey, a temporary postman, Blake had not been killed outright in the fall. Quite the contrary, in fact. Macey told the inquest that the driver had been thrown from the cart and was talking to the Australian soldier when he suddenly collapsed and died. It isn’t clear how or why the man collapsed, only that he was taken to Fargo Hospital and that Spicer was additionally treated for an injury to his hand.

There are a couple of issues here to address. The first is that the jury at the Inquest into Spicer’s murder in 1920 were told by the victim’s brother, Tom Spicer, that Sidney was a ‘happy-go-lucky’ kind of man who ‘had no enemies’ (Shot From Behind, Nottingham Journal 29 April 1920, p.1). Why the jury were not told of the earlier accident remains a mystery, as Spicer had been directly responsible for a man’s death in an area little more than a few miles from the scene of the crime. In the circumstances it seems unusual that Police were not pursuing revenge as a possible motive.

Also, the Inquest into Spicer’s death mentioned that the victim had experienced a permanent ‘injury to hand’ that had been sustained some years before. The jury was told that this was a ‘sporting injury’ (shooting accident) and no mention was made of the fact that Spicer had injured his hand in the collision that killed Blake.

Spicer was a well-known figure locally. He was a member of the local Buffalo Lodge (Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes) and his family owned sizable tracts of land in the area. A Quasi-Masonic group with little genuine claim to its Royal prefix, the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes (RAOB) might not be the all-seeing, all-powerful cabal made famous by Conspiracy Theorists but they would have held some influence in the local area. Representatives of four lodges in the area (Ye Herbert, Silver Badge, City of New Sarum and Good Fellowship) attended Spicer’s funeral (Nottingham Evening Post 30 April 1920, p.1). Conservative Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan is believed to have been among its members. Ironically, the Lodge was responsible for having supplied many of the Red Cross Field Ambulances most likely driven by Percy during the conflict. A good number of Conservative MPs made up the ranks. Salisbury MP, Augustus Allhusen (son of a German chemical manufacturer from Gateshead) and Mayor Arthur Whitehead were among them (the original order consisted almost entirely of actors from the Drury Lane district of London). Spicer was only a member of the ‘first degree’(Kangaroo).

There was, incidentally, an associate Order based at Blencathra Lodge in Penrith. The family of the man believed by many to have shot and killed Toplis, Norman de Courcy Parry, had been key patrons of the Blencathra Foxhounds.

In a peculiar twist it seems that Spicer’s cousin and namesake, Sidney T. Spicer of Leigh Court Farm near Salisbury was also shot in the head in a fatal shooting ‘accident’. Sidney T. Spicer was the son of Thomas Spicer, brother of Sidney’s father Stephen.

The rumours of a black-market trade coordinated by soldiers enlisted with the Royal Army Service Corps at Bulford, and featuring Spicer, was explored in Alan Bleasdale’s drama, The Monocled Mutineer. John Fairley and Bill Allison write in their book, that the Corps had become the “Mob of the British Army” and run by Corps-based gangsters, The Redskins. Witnesses describe some of the men carrying cut-throat razors (The Monocled Mutineer, Fairley & Allison, 2015, p.145). That their trade included alcohol is interesting, as it was a brewery cart that Spicer and the soldier from Sling had brought down during the fatal collision of September 1917.

Harry Fallows, whose account of a midnight joyride in Spicer’s car on the night of the murder resulted in the manhunt for Toplis, was also in the enviable position of being on duty as an orderly in the Vehicle Office on the night that the first car (the War Office ‘Sunbeam’ valued at £1000) was alleged to have been stolen by Toplis on Boxing Day 1919.

The man leading the Inquest into the murder of Spicer was J.T.P Clarke, deputy coroner of North West Hampshire and a captain in the Royal Army Service Corps at Bulford.

The are additional issues that need addressing too:

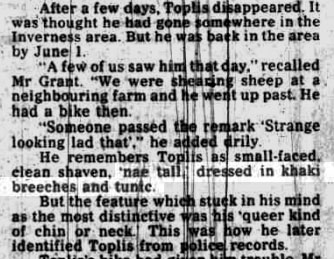

- The original suspect in Spicer’s murder was described as over 6ft in height and aged between 35-40 years of age. The initial press reports of the murder, drawn from Percy’s Service Records (no longer available) describe Toplis as being 5 ft. 5 inch and 24 years of age (Western Daily Press 29 April 1920). Tomintoul witness Alec Grant also described Toplis as ‘nae tall’ (Tomintoul Tramp, Aberdeen Evening Express 01 February 1978, p.10). Despite Grant going on to describe Toplis as a ‘shortish man’ the coroner in Penrith recorded Toplis’ height at the time of his death as 5 ft 9 (about average height at this time). This may been a deliberate attempt to bring it more into line with the height of the orginal ‘Sergeant Major’ suspect described by Spicer’s last known fares, a party of five men and women from Bulford Camp (Nottingham Evening Post 27 April 1920, p.1)

- Also generally assumed to be the victim of a robbery, the Manchester Guardian dated 27 April 1920 (page 9) reported that Hampshire Police were exploring premeditated motives for the shooting. Police were of the opinion that the time and location had been chosen specially as the car that Spicer was driving would have needed to have slowed. In their estimation, the driver would have been occupied in changing gears at the moment he was shot.

- The bullets used by Toplis to murder driver Sidney Spicer were modified expanding bullets (dumdums), traditionally used by terrorists and assassins. The Penrith Inquest recorded that dumdums were also found in his possession at the time of Percy’s death. Curiously, the bullets used on PC Greig during the shoot-out in Tomintoul were ball rounds and not dumdums. Dumdum bullets maximize internal damage, greatly reducing any chance of survival.

- Bullet holes and marks were also found at the rear of Spicer’s car (a grey, five-seater Darracq). Police could also not confirm if a revolver had been used. Is it possible that a rifle had been used, or that the fatal shot and a series of other shots, had been fired from outside the car?

- If car-theft was the motive Police were pursuing, then it was astonishing that Spicer’s killer had fired into Spicer’s head at point-blank range from the rear of the car. Any injury sustained in this fashion would have resulted in significant blood-loss, making attempts to sell the car to garage in the days following the murder almost impossible. Much had previously been made of the blood trail from the car to the hedge where the body was found (Grey Car Mystery, Nottingham Evening Post 27 April 1920, p.1).

- Key witness, Harry Fallows says Toplis took him on a joyride in the car within hours of the murder. Given the obvious damage to the car’s interior and upholstery likely to have arisen as a result of the immense trauma to Spicer’s head, how on earth did Fallows fail to notice both the bullet-holes and stains? The Police Surgeon at the Inquest described how he had found a wound in the head about a half-inch wide and four-inches deep in the scalp. The bullet had gone right through the brain.

- Fallows had arrived at Bulford Camp as a fresh recruit from Woolwich on December 12th 1919. Toplis deserted from Bulford Camp on 26th December that same year. Given such a small window of time in which to have made their acquaintance, it seems remarkable that the pair had formed the kind of special bond that resulted in the pair going on a midnight joyride to Swansea in April. Fallow’s army service record shows frequent absences.

- Spicer was described by Police as a ’particularly well developed and powerful man’ (Salisbury Inquest, April 29th 1920). Andover Police Surgeon, Dr E.A Farr was naturally of the opinion that it would take an equally strong and powerful man to drag the victim face downwards 40 yards along a road, across a ditch and up a bank and then place him behind a hedge (Hampshire Advertiser 01 May 1920, p.4). Spicer’s brother-in-law also described Spicer as an ‘extremely powerful man’ , weighing approximately 13 stone. He describes seeing a fight in which his brother-in-law disposed of three Australian Soldiers single-handed.

- Police were telling the Press that Spicer had large sums of money on him at the time of his death. This was disputed by his widow and employers at the taxi-firm (Last Fare of the Victim, Lancashire Evening Post 27 April 1920, p.2.

The following press report on the death of Richard Blake is taken from the excellent Salisbury Inquests blog

Runaway Horses – September 14th 1917

The story of an accident attended with fatal consequences near the Stonehenge Inn was the subject of an inquest held by the Coroner for South Wilts (Mr F H Trethowan) at Fargo Military Hospital, on Wednesday. The victim of the mishap was a brewer’s drayman, Richard Charles Blake, of Foundry Lane, Reading. He was 51 years of age.

George King, of Reading, a drayman in the employ of Messrs Simonds, identified the body and said he saw Blake at 9.15pm on Monday leaving No 18 Camp, Larkhill. Blake was then perfectly sober. The horses he was driving were perfectly safe and quiet, and Blake had three lamps alight on his dray.

Lieut Shepherd, of the RGA, stationed at Great Bedleigh, Essex, said he was coming along the road from Stonehenge Inn about 10pm, when a car passed from behind going at a considerable rate. He was on a wagon drawn by six horses and the car passed on their off side. After the car passed he noticed the reflection of lights to the off side of the road and then heard runaway horses, and saw them pulling the dray and the driver sitting back endeavouring to pull them up. He jumped down to try and stop them. As the dray drew level the near hind wheel caught the curve and threw the driver off the dickey. He picked him up and laid him on the pavement. The driver of the car then came up and complained about his hand. A medical officer saw both men and they were afterwards removed to the Fargo Hospital.

In answer to the Coroner, the witness said he did not notice whether there were any lights on the dray.

Gordon Macey, a temporary postman, said he was going towards Durrington Camp Post Office when he saw a car coming towards 3a Camp at about 10 or 15 miles an hour. Hearing a “bump” he turned round and saw the runaway horses coming at a considerable speed, the driver trying to check them. He ran after the horses and later saw the driver of the dray, who had been thrown out, talking to a soldier, and then fall down. After the collision the dray had no lights on it.

Arthur Tanner, motor driver, of 81, Culver Street, Salisbury, said that he was riding beside the driver of the motor car, and there was an Australian also in the car. They followed a military wagon, which, he believed, was drawn by four mules and was going to pass when a brewer’s dray, without lights, came up. There was not room for them to pass, and the car struck the off wheel of the beer wagon. The horses ran away. Spicer got out of the car and ran after them. He was positive there were no lights on the beer wagon. At the time of the collision the motor-car was going about four miles an hour.

In reply to a juror, he said the did not see the horses until they were on top of them.

Sidney George Spicer, of Coombe Road, Salisbury, motor owner, and the driver of the car, said he was passing the military wagon when the dray approached, without lights, and the horses trotting fast. He put on his brakes and stopped the car and the dray collided with it. He was as close to the wagon as he could get.

In reply to questions he stated that he was driving slowly because he was expecting his passengers to tell him to stop. He was three or four yards from the horses when he first saw them, and could not hear them because the army wagon was rattling.

PC Adlam, stationed at Durrington, said that he went to a point on Durrington Road about 300 yards from the Stonehenge Inn and saw the wagon lying on its near side. The –ole was smashed and the tilt damaged. He found two lamps, one front lamp was on the floor of the wagon inside, and a rear lamp was standing on the tailboard. There was some candle in the front lamp. The car was badly damaged on its left side.

Capt. Phillips, RAMC, of Fargo Hospital, said Blake was brought in unconscious and with a small wound at the back of the head which had been dressed. The cause of death was injuries to the head.

The Coroner, addressing the jury, said the evidence was most unsatisfactory, and they would have considerable doubt in deciding exactly how the collision occurred. They could only find a verdict of manslaughter against the driver of the car if they came to the conclusion that his driving was either reckless or that he was driving in such a way that it was obvious he did not care whether any one was injured or not. A slight act of negligence was not sufficient for them to find a verdict of manslaughter, but if they did find that there was any neglect on the part of the driver which did not amount to gross negligence they could censure him. In that case the verdict would be one of accidental death.

In giving the verdict the Foreman said the jury found one of “accidental death” and did not wish to add any rider to it.