Just weeks before Russia February Revolution swept Tsar Nicholas II from power, a crack team of Russian intelligence specialists, diplomats and Anglo-Russian Oligarchs pooled resources to form the United Russia Societies Association. As Britain pinned its hopes on the incoming Kerensky Government, Liberals and Conservatives In Britain looked forward to a whole new era in Anglo-Russian trade relations. Then something rather unexpected happened.

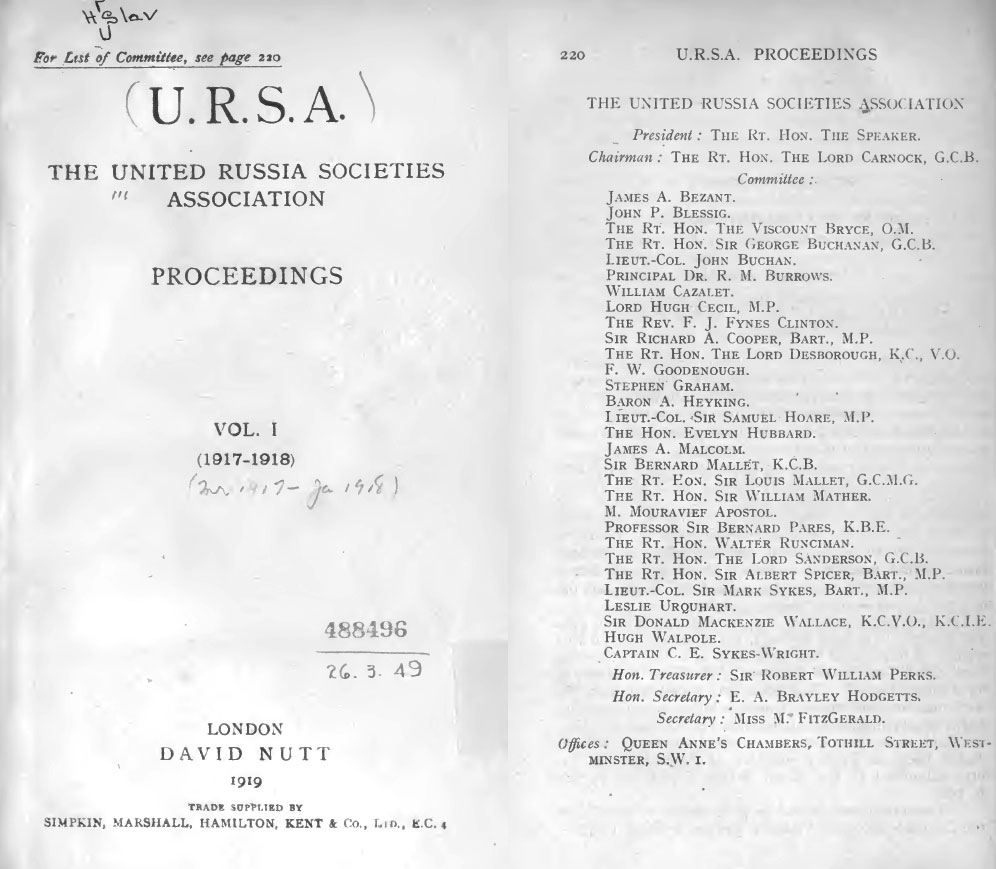

The United Russia Societies Association, or U.R.S.A as it became known, was James A. Malcolm’s ambitious attempt to combine the forces of the drooling learned Russophiles and the common-or-garden military propagandists and Intelligence officers of war-time Britain and hammer them together into a more combat-ready cadre of skilled enthusiasts and educationalists. [1]

The first of these groups was The Russia Society, whose aims were put forward in a press release produced by Commons Speaker James Lowther (Earl of Ullswater) and James A. Malcolm:

The objects of the Society are:— To promote and maintain a permanent and sympathetic understanding between the peoples of the British and Russian Empires by all legitimate means, so that German intrigues may in future be nullified; to disseminate knowledge of each other; among each other, in a simple and popular manner; to encourage reciprocal travel and social intercourse and generally to establish mutual friendship its widest and frankest sense. The Society will not directly concern itself in the development of commerce and finance between the two empires, but the attainment of its objects cannot fail to exercise a beneficial influence upon the business relations of the two great Empires and their friends. A permanent understanding between Britain and Russia, it is argued, means permanent peace for the world.[2]

At the Society’s inaugural meeting at its 47 Victoria Street address it was decided that an annual subscription would be set at 10 shillings. There would also be a subscription for families and institutions at £1. At its next meeting at the Speaker’s house March 1915, a telegram was read from the King offering “hearty sympathy with every effort made to promote and maintain and a complete and lasting relationship” with Russia. Rising before its members, Neil Primrose, the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of Foreign Affairs explained that there was nothing to be gained by simply “professing friendship” anymore. It was the duty of both countries to truly understand each other’s “national aspirations”. There had been a barrier of “ignorance and prejudice” for too long, before adding that Russia differed from Germany in one major respect: unlike Germany, Russia’s aspirations were “natural and legitimate” and it was unlikely it would ever be satisfied with the current territorial arrangements. Things desperately needed to change, and change would start with first acknowledging its cultural and economic worth. In contrast to Germany, the products and resources that Russia had to offer would be of “genuine” value to the rest of the world. For any member of the meeting who still doubted the integrity of his claims, Primrose made one last admirable bid: with lasting prosperity would come lasting peace. [3] As the grandson of Baron Mayer de Rothschild, it was a grim irony indeed when just two years later in November 1917 Primrose would die in a battle to liberate Palestine. Just two prior to Primrose’s death Balfour had published his truly momentous Declaration, and in whose complex matrix of intrigues Major Burdon and the U.R.S.A group would become increasingly embroiled.[4]

The man who had perhaps, done more than anybody to bring the new Association together was Harry Cust, the celebrated first cousin of Robert Hobart Cust whose letter to H.A. Gwynne in spring 1920 had first revealed the extent of the collaboration between his good friend Edward G.G. Burdon and former pilot, George Shanks on the first English translation of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Subsequently adopted by Hitler to justify Nazi persecution, this anti-Semitic text produced in Tsarist Russia in 1905 described a totally fictitious Jewish plot for global domination. Shanks is alleged to have borrowed a copy from the British Museum, completed the translation with Major Burdon and printed off an initial run of 30,000 copies.

As the much respected founder of Britain’s first propaganda bureau, the Central Committee for National Patriotic Organizations, Harry Cust had been among the first to see that a succession of British companies had been losing overseas orders to their German competitors both before and during the war. To reverse this trend, Cust believed that radical change would be required in the country’s approach to business training. Whatever the outcome and whatever the losses, Britain would need to emerge from the war a much stronger trading nation. Sadly, on on March 1st 1917, the very day that U.R.S.A had been launched, Lord Weardale of the Anglo Russian Friendship Society addressed the inaugural meeting with a look of bewilderment and a heavy heart: he had the sad duty to inform all who had come to the meeting that their friend and mentor, Harry Cust had died suddenly that morning at his house in Kensington, [5] a heart attack brought about by an acute bout of the flu. He was 55 years old. His death on March 2nd 1917 would come just six days before the February Revolution in Russia. It’s believed that the intense pressure of his work at the Patriotic Organisation had finally taken its toll. [6] Despite there being very little in the official record that might explain his interest in Russia, there are some clues to be found in a preface that Cust had written for Russia and Democracy: A German Canker in Russia, a book by Serbian scholar and former mercenary, Gabriel de Wesselitsky.[7]

For the two years that followed, U.R.S.A would grow impressively in size from a dozen or so members to 700 members. When Malcolm’s Russia Society had been launched in March 1915, its activities and pursuits had a very sharply defined cultural focus: arts and crafts, music and dance, literature and language. Russia had entered the war on the side of the Allies and a fresh approach to an often fractious relationship was being taken by all those involved. The race was now on to repair that relationship. Just a few days prior to the group’s official launch, Russia, France and Britain had begun to exchange a series of frantic diplomatic cables agreeing the scope of a secret treaty that would see Constantinople and the Dardanelles, currently under Ottoman rule, divided in new territories between the Triple Entente.[8]

The association had been launched on wave of optimism and positivity. The advertisement placed by its founders, James A. Malcolm and Commons’ Speake, James Lowther in Zinovy N. Preev’s rather excitable ‘Rough Guide’ to events in Russia, The Russian Revolution and Who’s Who in Russia, rush-released in May 1917, sums up the buoyancy of feeling within the group: “TO PROMOTE and maintain a thorough, permanent and sympathetic understanding between the peoples of the British and Russian Empires by all legitimate means. TO ENCOURAGE reciprocal travel. TO STIMULATE the study and real appreciation of the two countries, their national qualities, languages, arts, literature, habits and customs of their Town and Country life, pastimes and sports. TO ARRANGE lectures, conferences, exhibitions, tours and to form branches of independent t societies with similar objects. To arrange Russian classes in Russian arts, literature and language, and to give prizes and scholarships for any subjects. To disseminate knowledge of each other among each other in simple, popular manner. TO ABSORB (if expedient), co-operate with, or assist in the work of other existing or future societies having common ends.” The last of the pledges couldn’t have been any more ironic: “Briefly, to establish a mutual friendship with Russia”. In light of the rather dramatic turn of events in October that year that brought U.R.S.A to a premature close, it might have been more accurate if it had read: “To establish a mutual friendship with Russia — briefly.” [9]

On the surface of things, the efforts undertaken by U.R.S.A couldn’t have been more different to the rather cautious attempts at rapprochement made in previous years, the press releases at pains to point out that the new association, unlike its predecessor, The Anglo-Russian Friendship would not directly concern itself “with development of Commerce and Finance between the two Empires”. And initially at least, Malcolm and his group was true to its word. For the twelve month period starting March 1917, the committee members organized a bounty of mutual beneficially lectures and events.

News from Russia

In April, founder of the British Russia Club, Prof Paul Vinogradoff reported back with his experiences of a recent trip to the Russian capital and the “strange notions and rumours” that were now circulating in England on the subject of the Russian Revolution. In a talk entitled, “Some Impressions of the Russian Revolution” he explained how the spirit driving the revolution had been slow and gradual. The tide of discontent could be seen rising day by day. It wasn’t just an accumulation of historical grievances that had done it, but the more practical urgent issues of bread and the prices of grain. The “hypnotiser” Rasputin and his other “quacks” had risen and been brushed aside and the formulas of abdication put to the Tsar in private had eventually been progressed. In May, the celebrated explorer and mining engineer Chester Wells Purington regaled an attentive audience with his Siberian adventures, and the various medieval merchant routes he had been forced to trace during his journey to the region. In June that year, Baron A. Heyking explained the differences that had long existed in the two country’s radically opposing views on duelling and notions of status, civic duty and personal honour among its officers and its nobles, a privilege that was now, he explained, likely to be extended to the lower classes.

In November 1917 it was the turn of Madame Mouravieff Apostol to explain the part played by the Russian Red Cross and the Zemtsvo unions in relief operations. [10] One month later in December, Norman Penty would guide us through the intense, romantic gloom of the composter Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and the signature characteristics of the Russian folk song. January 1918 would also get off to a benign and engaging start when Shanks’ uncle, Aylmer Maude, now heading U.R.S.A’s Board of Examiners, explored the complex relationship between the novelist Leo Tolstoy and “the present state of things in Russia.” Maude had been a key figure at U.R.S.A from the start, when he had been tasked with providing an education syllabus at one of its many language schools. Within a very short space of time over 4,000 students would enrol on his courses. [11]

By April 1918, the whole tenor of events and lectures had begun to change, the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 having brought the tours and cultural exchanges to an unseemly, staggering halt, and gradually eroding any the interest the British public may have had in learning about Russia’s art or hearing its Balalaika music. From this point on, reading U.R.S.A’s monthly ‘Proceedings’ becomes quite a painful experience, collapsing as it does from cheers of encouragement to cries of despair. If there was ever a physical violence one could do to ‘hope’ it would surely be this. That wasn’t the sound of regular protest or the lively cut and thrust of debate that you heard on the floor of British Parliament that autumn, it was the sound of the rug being pulled from under Britain’s feet. U.R.S.A moved nervously forward, hosting the usual kinds of events, cautiously optimistic that the Bolsheviks would be out by Christmas.

It was only after Lenin and the Bolsheviks signed the Brest-Litvost Treaty with Germany in March 1918 that the penny finally dropped. Contrary to all expectations the Bolsheviks had not only held on to power, they were indeed beginning to look rather comfortable. Within weeks, several members of U.R.S.A’s Executive Committee had resigned. They were replaced by men who not only understood the necessity of first-class propaganda but also had the skills and experience to match. Up the list went members of the former Propaganda Bureau in Petrograd like Sir Bernard Pares, Samuel Hoare and Hugh Walpole, and out went Lord Carnock, Sir Robert Perks, Sir Bernard Mallet and its founding patron, Sir Donald MacKenzie Wallace.

It’s well worth pausing a moment to look at other members of the U.R.S.A’s executive committee, as it represents quite a broad spectrum of economic, military, academic and political talents. Some of them we’ve touched upon already. James Lowther was the Speaker of the Commons and younger brother of paranoid anti-Semite, Gerald Lowther, the former British Ambassador in Constantinople. Among its less well known names was Royal favourite, William Cazalet, whose story we touched on earlier. William was the son of wealthy Moscow merchant and Jewish Homeland advocate, Edward Cazalet. Fifth on the list was Liberal Politician, Viscount James Bryce, British Ambassador to the United States during the 1909-1913 period. Next was Balkans expert, Dr Ronald Montagu Burrows was the principal at Kings College, London. A close associate of Sir Ralph Paget and Bax-Ironside, it was Burrows who had been almost single-handedly responsible for bringing Greece into the war as political ally to the Triple Alliance. A little further down was Reverend Henry Joy Fynes-Clinton, who had started his career as tutor to the families of industrial magnates and art collectors, Ivan and Mikhail Morozov in Moscow and ended it as champion of Protestant-Catholic rapprochement at the Anglican Papalist church, St Magnus the Martyr in London.[12] Below Fyne-Clinton on the list was the famously xenophobic Richard Ashmole Cooper, a chemical manufacturer who that same year would launch the short-lived British National Party with Sir Henry Page-Croft and spend the best part of the next five years attempting to derail the premiership of David Lloyd George over the notorious ‘Honours Scandal. Next was Francis William Goodenough, a pioneering marketing executive with the gas industry. The journalists among them included Stephen Graham, the famous travel writer who had become Russian correspondent for The Times of London under Lord Northcliffe in the years before the war. During his most active years for The Times Graham would become known for his idealised portraits of Russian Orthodoxy and spiritual matters, and for his 1913 book, With the Russian Pilgrims to Jerusalem – an account of his epic trip on foot to the Holy Land. Evelyn Hubbard was an Anglo-Russian merchant and director at the Bank of England, whilst the retiring Donald Mackenzie Wallace was the correspondent of The Times at the time of the Russo-Turkish War in the mid-to-late 1870s who had served as political advisor to Tsar Nicholas II on issues relating to the Middle East. The list had been calibrated to get the best from youth and experience, diplomacy and creativity — and the most formidable of business talents — to nourish both the trade and religious ties of the two great nations. The likes of Fynes-Clinton could help repair their spiritual bonds, whilst the Cazalet, Bezant, Hubbard and Blessig were on hand to help cultivate fresh trade.

At the annual meeting held at the house of its President, the Right Honourable James Lowther, the recently-returned British Ambassador to Russia, Sir George Buchanan explained the gravity of the situation: recent events in Russia had meant it was now necessary to have on U.R.S.A’s committee, people who has been in Petrograd and who were “personally acquainted with their conditions and everything else”. After the “kaleidoscopic celerity” of all that had happened in Russia, it was “only natural that there should be a “revulsion of feeling” against Russia whose defection would almost certainly prolong the war. If there was one thing that Buchanan was absolutely sure about, it was that Russia was a land of surprises and all the anarchy and chaos that was ripping through it now was unlikely to continue indefinitely. When the storm had passed and the Internationalists had been removed, it was the duty of groups like U.R.S.A to be at the forefront of easing the suffering and providing relief.[13]

The two men that Buchanan had played a personal hand in recruiting were those Titans of Anglo-Russian trade, James Aaron Bezant and John P. Blessig. Both men had amassed a considerable fortune in Russia over the years and there was a story going around that the Bolsheviks had stripped Bezant of a lifetime’s earnings in little more than 24 hours. Despite his refusal to renounce his British Nationality this proud and capable businessman had become one of Russia’s principal shareholders and the Managing Director of its biggest trading company. [14] The arrival of both men also marked the increasing influence of the oldest surviving group to have improved British and Russian relations: The Russia Company (or Muscovy Company as it was also known). It also marked the return of the Shanks family to the tale.

The Russia Company

Founded in the 1500s as a means of exploiting and expanding the Caspian trading routes between Persia and Southern Russia, The Russia Company had maintained an impressive monopoly on English-Russian trade until the early 1700s when it finally lost many of its remaining privileges under Peter the Great. In more recent years, the group had acquired a more titular reputation for maintaining the Anglican Churches of Moscow and St Petersburg, providing outreach to the British and American colonies that had remained in the major cities.[15] Its financial and political influence may have lessened considerably since the mid-1800s (officially at least) but it remained one of the few credible diplomatic channels between Russia and Britain, regularly bringing together the likes of Britain’s Sir Robert Peel and the Russian Ambassador in London, Baron Brunnow. Meeting for their annual dinner at the London Tavern in Bishopsgate, the pair’s respective entourages of fanatical Anglo and Russo ‘maniacs’ would mingle with many of the principal traders in the city, including representatives of the Bank of England and Her Majesty’s Customs. Toasts would be made, courtesies would be performed, and all suspicions and attempts at spying would be kindly turned-in at the door.[16]

In the Elizabethan period there were swarms of British merchant adventurers spread across every town of Russia, their enterprises and their factories virtually guaranteeing a monopoly of the maritime trade across the Tsar’s generous and vast dominions. Britain’s role in building the Russian navy had been just as prominent. By the time of Alexander II most of their once mighty privileges had been withdrawn, leaving about 5,000 British traders forced to confine their activity to the northern and southern extremities around Archangel, Voronezh and Tarangog on the Southern Steppes. Their only significant influence in the central belt was in the cotton mills of St Petersburg and the extensive print works of Egerton Hubbard. Egerton’s son, the Tory MP Evelyn Hubbard would not only serve as part of U.R.S.A’s 1917 executive he would also earn the distinction of being the last official governor of the once mighty Russia Company. [17]

According to Julia Mahnke-Devlin, author of Britische Migration nach Russland, the man who was appointed legal warden of The Russia Company in Moscow in 1878 was James Shanks, the grandfather of Burdon’s co-translator George Shanks, and almost certainly an associate of Egerton Hubbard, the father of the man who now served on the U.R.S.A executive. Curiously enough, the appointment of Shanks as Church Warden at The Russia Company in 1878 coincided with the end of the Russo-Turkish War, an enormous concern to the British at that time. The Ottoman treatment of Armenian Christians had drawn a fiercely divided response from Britain, whose self-restraint and counsel during a potentially explosive period was rewarded with an invitation to take control of Cyprus. The only thing preventing the Russians seizing the Turkish capital had been a British Fleet. Under pressure from the Brits, the Russians brokered a peace deal with the Turks. [18] Shanks’ patronage at The Russia Company during this period had been defined by the building of the St. Andrew’s Anglican Church (‘a little corner of England’) in his adopted hometown of Moscow, and the various ‘charitable’ projects that Shanks undertook in the church’s name. [19] Among the church’s sponsors were the 19th Century Moscow Industrialists, Bernhard Wilmar Wartze and Robert McGill, both of them members of Shanks’ extended family and both of them among the first exporters of modern capitalism to the primitive rural frontiers of Tsarist Russia. [20]

By 1915 the ghosts of an earlier power-struggle among the world’s merchants had returned to haunt the current one, making the appearance of Iraqi-Armenian, James Aratoon Malcolm on the executive committee of U.R.S.A all the more curious. Malcolm had built his reputation as a Persian trader of some considerable worth, and the revival in fortunes of The Russia Company just happened to coincide with Britain’s attempt to breathe fresh life into Caspian trade, and resurrect, in spirit at least, the objectives of the Euphrates Valley Railway. History was repeating itself. The Russian Company had been founded for the purpose of exploiting trade between Persia and Russia, now it was being revived on that same principle. The Press in Britain weren’t ignorant of this coincidence either.

Within days of it being announced that the Russian Caucasian Army had captured 2,300 Turks in Mush in Southern Armenia on the Persian frontier, [21] readers of the Liverpool Journal of Commerce were learning about plans for a new Anglo-Russian shipping bank that was being organised by traders in Moscow.[22] By September 1918, the ghosts of Persian fortune were returning with renewed vigour, The Times of London commenting that “although never in identical terms, history occasionally repeats itself, as it is doing now for the first time in the Caspian, and the roads leading to it from north and south” which has assumed “important interest” to the British. Some three hundred years may have elapsed since The Russian Company’s founder Anthony Jenkenson had heroically hawked his silks and woollens between Archangel and Persia and raised the lofty Royal Banner of England above its seas, but the spirit that had carried him forward was being channelled into whole new trading opportunities.[23] Among those poised to make a killing were the Ural Caspian Oil Corporation (controlled by Anglo-Armenian nobleman, Calouste Gulbenkian, Henri Deterding and Royal Dutch) and Leslie Urquhart’s Russo-Asiatic, whose share prices looked to regain some momentum as a result of ports being reopened in spring 1917. [24] In 1920, the Communist Party of Great Britain was quick to point out the Ural Caspian Oil Corporation and the British Trade Corporation, established by Royal Charter by Lord Faringdon and Henry Cust’s ‘Souls’ mate, Arthur Balfour within weeks of the February Revolution, had been formed for the specific purpose of facilitating trade in the territories being commanded by White Russian Generals Deniken and Wrangel who were presently engaged in war against the Bolsheviks.[25] The issue was taken up in full in Parliament by Cecil John L’Estrange Malone MP in August 1920 when he openly questioned the financial conflict of interests that certain members on the Front Bench and their friends now had in Russia. The Ural Caspian Oil Corporation was subjected to particular scrutiny.[26]

A Storm Cloud Gathers

With the cash windfalls of the war being spent before Britain and its Allies had been able to so much as raise a flag, it must have come as a tremendous shock to find that Russia, on whose fortunes in Europe the Brits had depended had, without warning, handed a late and humiliating equaliser to Germany. Even if Germany had failed to triumph outright, the ‘Bolshe’ had handed the ‘Boche’ a not totally shameful escape route. And as the penny began to drop, the claws sharpened and the rancour set-in. U.R.S.A’s lectures took on a meaner edge: Lenin, like Rasputin before him, was a German Agent and any Bolshevik who wasn’t a German agent were “dark horses … the scum which the tidal wave of Revolution had sprung up” and who now dominated the Workers parties.[27]

In February 1918, the Russian barrister L. P. Rastorgoueff, who had previously given talks on everything from the legal rights of British firms in Russia to the ‘Disabilities of Russian Jews’, explained that the atrocious pogroms being carried out now in the Ukraine and Poland were a result of “the unscrupulous and oppressive manner” that their landlords, the Jews had imposed on their religious affairs. The Jews, he went on formed practically all of the Polish middle class and retained their estates with all feudal rights.[28] It was a line that was trotted out every time there was a massacre. There nothing really new here. The anti-Semitism of the group had always found itself being expressed in the most casual of ways. Writing shortly after his return from his five year tour of Russia in 1875, the group’s patron Donald Mackenzie Wallace had described the Russian merchants he had encountered as being “comparatively honest in comparison” with the Jews, Greeks and Armenians her had met, and was at a total loss to explain how the Jews managed to undercut their Russian rivals: “I cannot understand. They buy up wheat in the villages at eleven roubles per Tchetvert, transport it to the coast at their own expense, and sell it to the exporters at ten roubles! And yet they contrive to make a profit!” As “cunning” as the Russian trader was, their “brother” simply had no chance of competing.[29] He may have reserved a modicum of sympathy with the violent abuses the Jews had been obliged to endure over the years, but as always, there was a peculiar sense of moral justice attached to these accounts, as if the violence meted out to the Jews of Russia had somehow been determined by some perceived transgression of a universal law. Like many Scots, had framed Jewish Reactionarism during the 1905 Revolution in more positive terms: “Of the recruits from oppressed nationalities, the great majority comes from the Jews, who thought they have never dreamed of political independence, or even a local autonomy, have most reason to complain of the existing order of things. At all times they furnished a goodly contingent to the revolutionary movement, and many have belied their traditional reputation of timidity and cowardice by taking the part in the very dangerous Terrorist enterprises”. Wallace put the success of their various revolutionaries enterprises like the Bund and the Social Democratic Labour Party down to their greater “business capacity”. Centuries of oppression had, moreover “developed in the race a wonderful talent for secret illegal activity, and for eluding the vigilance of the Police.” [30] As long as the actions of the Jews were supporting British policy, it seems their skills as insurgents were viewed not as malicious in nature but resourceful, rather.

A few weeks after L.P. Rastorgoueff’s address in March 1918, Sir George Buchanan, the former British Ambassador who had been forcefully ejected from Russia in January that year [31], warned guests at an U.R.S.A dinner in Piccadilly that the “storm cloud was dark” over that great nation. The “thunders were rolling and re-echoing from north to south, from east to west, and lightning was flashing, and everything looked black”. It was chaos. Whatever it was, this was not the will of the people. The Soviets in charge were not Russians but “Internationalists” who were poised to accept a peace “determined by German Imperialism”. Russia was not dead she merely needed “moral oxygen”. With the help of U.R.S.A she could be revived. God willing, he hoped he lived long enough to see a new Russia arise from the present chaos. He finished his speech by quoting Tennyson: “That good may fall. At last far off, at last to all. And every winter change to spring”.[32] Lecturing at Kings College, U.R.S.A’s Sir Bernard Pares did his best to polish-up that same silver lining. It was “end-of-war sickness” that Russia was suffering from, and not some Marxist rising. The beginning of Bolshevism had been “pure war weariness, and nothing else”. But doing nothing was not an option. Britain now needed men in Russia. An organized body like the United Russia Societies Association could co-ordinate and give impact to public interest in these matters. The universities and colleges could help by acting as conduits with Russia’s large commercial entities and improving the language skills necessary to prevent further German penetration. [33] A no less direct appeal had been made in November with former Intelligence man, Samuel Hoare in the chair. The Allies’ Russian Policy had been rendered useless by “vacillation and inconsistency”. A “policy of non-Intervention was not impossible”. Sooner or later Britain would be dragged into a Russian policy against its will, and the sooner they took control of that policy the better. To counteract the effect of Germany going to Russia, Britain should get there ahead of them.[34]

The pushing to the fore of hard-faced incorrigibles like Oliver Locker Lampson and slippery agent provocateurs like Robert Bruce Lockhart the following year, suggested a sudden sharp change in tone and direction.[35] The death of U.R.S.A’s much respected patron and veteran of the Russo-Turkish War, Donald Mackenzie Wallace in January 1919 marked the end of its moderate phase, and the beginning of a period in which the group’s steely carbon basis was being hammered and ground into something a little more lethal. All the lavish positivity and ebullience that had marked U.R.S.A’s formation just 12 months previously was as quiet as the snow falling on the unmarked graves of the Romanovs on Porosenkov Log. The music, arts and dancing that had graced its theatres and discussion rooms was now inaudible beneath the rumbling peal of loathing. At U.R.S.A’s offices at 123 Pall Mall, only the whirring cogs of revenge and the muffled drone of desperation could now be heard.

Endnotes

[1] URSA is the Latin for ‘Bear’. The significance of the acronym wasn’t lost on the founders of the association who remarked that the initials were not a very bad combination for a Society interested in the Russian bear. See: U.R.S.A Proceedings, Annual Meeting, March 2nd 1917, vol.1, 1917 -1918, London, David Nutt, p.4.

[2] British Friendship with Russia, Objects of A New Society, The Times, January 23 1915, p.6

[3] Understanding Russia, The Times, March 12 1915, p.9

[4] It was Lionel Walter Rothschild, the 2nd Baron Rothschild who had played such a critical role in putting the Balfour Declaration together.

[5] U.R.S.A Proceedings, Annual Meeting, March 2nd 1917, vol.1, 1917 -1918, London, David Nutt, p.5. In 1877 Liberal MP Lord Weardale had married Countess Alexandra Tolstoy, a relative of the famous novelist, bringing him into the orbit of Tolstoy’s friends (and Goerge Shanks’ uncle and aunt) Aylmer and Louise Maude. Weardale was a close ally of Lord Curzon.

[6] Death of Mr. H. Cust, The Times, march 3rd 1917, p.9

[7] Gabriel de Wesselitsky was a Serrbian national born in the Royal Province of Tsarskoe Selo in Russia in 1841. In his twenties and thirties he fought alongside Italian revolutionary Garibaldi. He also co-founded the Foreign Press Association.

[8] This became known as the Constantinople or the ‘Straits’ Agreement, which was designed to minimize any chance of future aggressions by Germany and further inroads into the Middle East. The discussion period lasted from March to April 1915. As a result of the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 the agreement was never implemented.

[9] The Russian Revolution and Who’s Who in Russia, Zinovy N. Preev, J. Bale & Danielsson, 1917 (back pages).

[10] Madame Nadine (Tereschenko) Mouravieff Apostol was the wife of Vladimir Vladimirovich Mouravieff-Apostol-Korobyine. Their son Andrew Mouravieff-Apostol would subsequently marry, Ellen Marion Rothschild.

[11] Derby Daily Telegraph 09 February 1917, p.2, U.R.S.A, The United Societies Association, Proceedings, Vol.1, 1917-1918, David Nutt, London, 1919

[12] Mikhail Morozov was an associate of George Shanks’ uncle, Léon Lvovitch Catoire at several banks and trade organisations in Moscow. They were also patrons of his composter brother, George Catoire.

[13] U.R.S.A Proceedings, Annual Meeting, March 22nd 1918, vol.1, 1917 -1918, London, David Nutt, pp.206-220.

[14] Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail 27 June 1936, p.2

[15] According to a 1989 essay by Chester Dunning, the spoils of trade and influence were so great under The Russia Company that King James I had plans to establish a Protectorate over North Russia.

[16] The Russia Company, Morning Post 04 March 1844, p.5. U.R.S.A Proceedings, Annual Meeting, March 22nd 1918, vol.1, 1917 -1918, London, David Nutt, pp.206-220.

[17] The English in Russia, Globe 12 January 1877, p.6

[18] Congress of Berlin, 1878

[19] Britische Migration nach Russland im 19, Julia Mahnke-Devlin, Jahrhundert: Integration – Kultur – Alltagsleben. Germany, Harrassowitz, 2005, p.182. In October 1917, the Bolsheviks used the tower of the church to launch a machine-gun defence of the Kremlin against Kerensky’s provisional government. It was closed in 1920 and its library, archives and valuables confiscated by the Bolsheviks. The church was fully restored in the mid-1990s by President Yeltsin. James Shanks has been memorably described by historian Harvey J. Pitcher as ‘the pillar of the British Church’ in Moscow.

[20] The German-born, Bernhard Wilmar Wartze was the father-in-law of James Shanks Jnr, whose ‘Burke’s Grove’ home in Beaconsfield features in the ‘next of kin’ section in the 1916 service records of George Shanks. James Jnr had married Isabella Henriette Wartze in Moscow before moving to Britain.

[21] Russian Victory over the Turks, The Times, August 15 1916.

[22] New Russian Shipping Bank, Journal of Commerce 22 July 1916, p.4

[23] The Caspian in Peace and War, Romance of British Trade, The Times, September 20th, p.5

[24] Stock Exchange, Buoyant on the War News, The Times, March 20 1917, p.10. Leslie Urquhart sat on the Executive Committee of U.R.S.A.

[25] British Trade Corporation, Communist (London) 12 August 1920, p.8. This was in partnership with the Trade Indemnity Company Ltd.

[26] Hansard, Commons Chamber, Russia And Poland, Progress Of Negotiations, Statement By Prime Minister, Volume 133: debated on Tuesday 10 August 1920

[27] U.R.S.A, Proceedings, p.54

[28] U.R.S.A, Proceedings, p.172.

[29] Russia, Vol.I, D. Mackenzie Wallace, Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1877, p.276. Like Harold Williams, Wallace had served as Foreign Correspondent in St Petersburg for The Times of London

[30] Russia, Vol. II, D. Mackenzie Wallace, Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1877, pp.463-464. Wallace was the former Foreign Correspondent of The Times.

[31] Hansard, House of Commons Sitting, Russia, Sir George Buchanan, 21 January 1918 vol. 101 c642. Answering a question put to him Arthur Lynch MP, the British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour explained that Buchanan was ‘only home on leave’.

[32] Russia’s Downfall, A Disregarded Warning, The Times, March 2nd 1918.

[33] Work for Britain in Russia, The Times, December 18 1918, p.10.

[34] British Policy for Siberia, The Times, November 15th 1918, p.15

[35] Russia Under Lenin, Evening Mail 15 January 1919, p.3

поддельные новости: The Monocled Mutineer and the Red Under the Bed documentaryTweets by repeat_the_past