Whether you’ve seen the films or read the books, the thing that everybody seems to remember most about The Great Gatsby is the fantastic house and the riotous parties. But where did Scott get his inspiration for the house? And what was the house intended to say? At the time the novel was written Scott Fitzgerald was at a crossroads: he could either cling to his Catholic past or row furiously with the tide into an exciting, uncertain future. For answers, Scott looked to his old hero, Shane Leslie and his new hero, James Joyce.

Despite the increasing personal and religious space that developed between F. Scott Fitzgerald and his Catholic boyhood mentor, Shane Leslie in later years, it was perhaps Leslie and James Joyce’s Ulysses that had the two greatest impacts on the creation of Scott’s most famous book, The Great Gatsby. Both men were Irishmen of astonishing abilities, but the pair couldn’t have been more different: Joyce was the snarling ex-pat subversive who stood accused of ‘literary Bolshevism’ and Leslie was the handsome, respected diplomat from the upper echelons of Anglo-Irish society who dined with Kings, Queens, Presidents and Popes. Joyce wouldn’t meet Scott in person until after The Great Gatsby had been written, by which time his youthful infatuation with the author had turned him into one of his most ‘devoted’ (and most embarrassing) admirers. Leslie was someone that the author had known since his days at Newman School for Boys, Scott’s prep school in New Jersey and represented everything that was dazzling about the world’s past. Joyce, on the other hand, represented everything that was compelling about its future. Beyond that, practically the only thing that Joyce and Leslie had in common was the fact they were both writers — and heroes of Scott Fitzgerald’s.

Of the two, Leslie was probably the one more conscious of his impact on Gatsby, recalling in a story published in The Times of London in the 1950s how he had taken the young novelist to Long Island and “launched him among the great country houses that then clustered the Island”. It was this trip, according to Leslie, that had given the young man his first taste of the fabulously wealthy and successful social elites that made up the bedrock of life on the Island. This was New York’s Gold Coast, a white celestial city of follies, chateaus and fake castles. Among those who had made their homes here were the Vanderbilts, the Astors, the Morgans and the Belmonts. The Titans of Wall Street had taken the soft clays of the fish-shaped island and remoulded it in their own image. The last thing to have shaped the Island this emphatically had been the glaciers. As a result of their movements in the last ice-age, a high elongated ridge had been deposited along Port Washington on the Island’s northernmost shore. The soft, sedimentary rock didn’t allow you to make skyscrapers here but the houses they did build were no less overwhelming.

Among the first of these great houses was The Cedars in Sands Point, the opulent 300-acre Catholic paradise owned by Shane Leslie’s brother-in-law, William Bourke Cochran. Sands Point, in Greater Port Washington, stands at the very tip of the Cow Neck peninsula some 25 miles east of Manhattan. This constantly shifting land, ground down and eroded by the melting edge of the waters would eventually become the ‘East Egg’ of the Gatsby novel: the seat of ‘Old Money’ in the fool’s kingdom that was New York. With its own Catholic Church and own stables The Cedars, now demolished, was among its finest, but not its most outrageous.

Reviewing Scott’s short but comet-like streak across the world’s atmosphere in the 1950s, Leslie says that The Great Gatsby is the one book he had helped the most with and that The Cedars was where it all took shape. The dazzling images that Scott would see here would be burned into his retinas for years to come: “the grand life of the multi-millionaires all around went to his head”, wrote Leslie. Leslie, who had married his wife Marjorie at the house in June 1912, recalled an occasion in which he had found Scott in his pyjamas solemnly sharing his young philosophy with the Cockran’s dog in the drawing room of their house. Although he never dreamed “he would touch fame”, Leslie would enthuse that he had been “the most lovable of protégés”. [1]

Mention The Great Gatsby to people today and there’s generally one reaction people come back with: that fantastic house, those amazing parties! Every producer of every film that’s ever been based upon the novel knows that if you don’t get the look of the house right or the riotous scale of the parties right then whatever you throw at it next will never really fall into place. It would be like celebrating New Year’s Eve without the fireworks. When a novel is usually adapted for film most of the collateral — artistic, conceptual or otherwise — tends to be invested in the book’s main hero or heroine. Take the stories of Arthur Conan Doyle. A film or TV show can be as faithful to the book or bear practically no relationship at all to the book, but if you don’t get the character of Sherlock right the whole thing falls flat on its face. You can take him out of London and put him in New York, make him a 80 year old geriatric or a swanky young man of twenty. You can drag him and his diminutive, dry-witted sidekick, Dr Watson into the 21st Century without so much as a pipe or deer-stalker in sight, but if the star of the show doesn’t deliver the ‘classic Sherlock’ then it isn’t really Sherlock at all. But the star of the show in Gatsby is the house. You only have to look at the trailers of Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 version of Gatsby to appreciate that it wasn’t an A-Listing the film bent dollar and buck to buy, but a Grade-I Listing.

Whilst practically everything you see of Long Island and New York in Luhrmann’s movie is CGI, the roving aerial view of Gatsby’s house that literally explodes from the screens in the previews is a computer-generated mash-up of two real life dwellings on Long Island: a sumptuous colonial-style mansion at Kings Point and an imitation castle in Huntington. This is how it was for Scott too. Gatsby’s mansion wasn’t one building but several that had been beautifully fused together in the author’s imagination.

As the film starts rolling and we get that colossal structure of a house rising before our eyes, the Bryan Ferry Orchestra strikes up the most decadent of Jazz Age takes on Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black, its smoky, lo-fi production almost impossible to differentiate from the scratchy gramophone recordings of the 1920s period. If Faust or Mephistopheles had grabbed the microphone and started crooning at The Cotton Club in June 1922, this is what it might have sounded like. Ferry had produced a ‘factual imitation’ of the Jazz records of the period. The recording has a crude yet exquisite energy. It sounds tinny. It sounds authentic.

The 14,551 square-foot colonial-style mansion that we feast our eyes on for the duration of the movie stands in an area of Long Island just north of Great Neck, the ‘less fashionable’ Gold Coast district that Scott and Zelda moved into to write the novel. So in this respect it really is a West Egg mansion. The other half of Lurhman’s composite vision is Oheka Castle, the former home of the German-born Wall Street banker, Otto Hermann Kahn. It was Otto who conceived of the sunken French gardens and the ludicrously gothic turrets that beguile the viewer in Luhrmann’s film. ‘Factual imitations’ of French chateaus were reasonably common on Long Island’s Gold Coast in the early part of the twentieth century. The other Gatsby house, the one used in Jack Clayton’s 1974 movie adaptation of the novel is Rosecliff and Rosecliff stands at 548 Bellevue Avenue in Newport, Rhode Island. The problem for the producers at the time the movie was being filmed in 1973 was that most of the really opulent properties at Kings Point on Long Island had by this time fallen into a fairly wretched state of disrepair — and there was no CGI around in those days to perform anything in the way of digital restoration. It was all down to location, and the location manager and his crew did a commendable job of finding something that evoked the spirit of the original whilst tipping a nod and a wink to that most famous of American mansions — the White House.

If there is one thing that becomes clear pretty quickly, it’s that looking for the one true source of Gatsby’s house is like looking for the source of all life on earth. The Island is teeming with possibilities. As one house was completed another architect would be hired and try and copy its designs. The French-trained architects of fantasy and romance on the Island like Addison Mizner and Richard Morris Hunt were cribbing from each other, left right and centre. In this hugely competitive atmosphere the traditional values of originality were abandoned in favour of opulence and a sentimental regard for the past. Houses were no longer meant to look just beautiful and iconic but also vaguely familiar. A Xerox phenomenon was erupting in the building trade. Looking for Gatsby’s house was like looking for the one true reflection in a House of Mirrors. Imitation after imitation seem dominate the isle of dreams. But for those who are prepared to look the clues are in the novel itself.

A factual imitation of some Hotel de Ville in Normandy

The house that Scott most likely had in mind when writing the novel seems to have had elements of all of the houses that caught the imaginations of movie directors, Clayton and Luhrmann: there’s a little bit of Rosecliff, a little bit of Oheka Castle and a fairly liberal pinch of another one which I am going to introduce to you shortly.

The actual novel describes Gatsby’s house as a ‘factual imitation of some Hotel de Ville in Normandy”. Rosecliff is a fair choice in this respect as the house had been built as a ‘factual imitation’ of the Petit Trianon in Versailles by Theresa Fair Oelrichs in 1909. Theresa, the daughter of the Belfast-born ‘forty-niner’ James Graham Fair, had based its design on the home of Marie Antoinette and her ‘Sun King’ husband, King Louis XIV of France, a fiercely devout Catholic (and ego-maniac) who in the late 1700s mercilessly hunted down France’s ‘Hugenot’ Protestants almost to the point of extinction. The Petit Trianon was a palatial annexe on the King’s more extravagant Grand Trianon. Both Theresa and her husband, Herman Oelrichs were Catholics themselves, so its reasonable to presume that there may have been some religious motivation in the way the house was conceived and designed. Whether or not Rosecliff had its own ‘Hall of Mirrors’ as the original had in Versailles isn’t known but it would certainly have made an intriguing figurative prop in the conflict being played out in the novel between illusion and reality.

Despite all of this, the description of Gatsby’s house that Fitzgerald provides in the novel are quite specific in certain respects. The book mentions that it was a relatively new build that had your classic square tower on one side under a thin beard of ivy — a “colossal affair by any standard”. We also know that it occupies a 42-acre site at the northernmost tip of Kings Point (West Egg) just fifty-yards from the Long Island Sound and has a ladder of marble steps that provide a gateway to the house. The author tells us a little bit about the layout of the grounds too. The house sits in over 40 acres of lawn and mature, wooded gardens and boasts its own marble swimming pool. In the gardens there is the “sparkling odour of jonquils and the frothy odour of hawthorn and plum blossoms.” This is a lovely symbolic touch from Scott, as Jonquils are traditionally associated with Narcissus. The flowers stand for inspiration, rebirth, creativity, vitality, and material success. To some Victorians the Jonquil (a type of Daffodil) also symbolized forgiveness or a desire for the return of affections. As the first flower to bloom at the end of winter, the Plum Blossom, which Scott also mentions, is representative of a triumph over adversity and nature, and is about as pertinent to Jay Gatsby as one could probably get in a single flower [2]

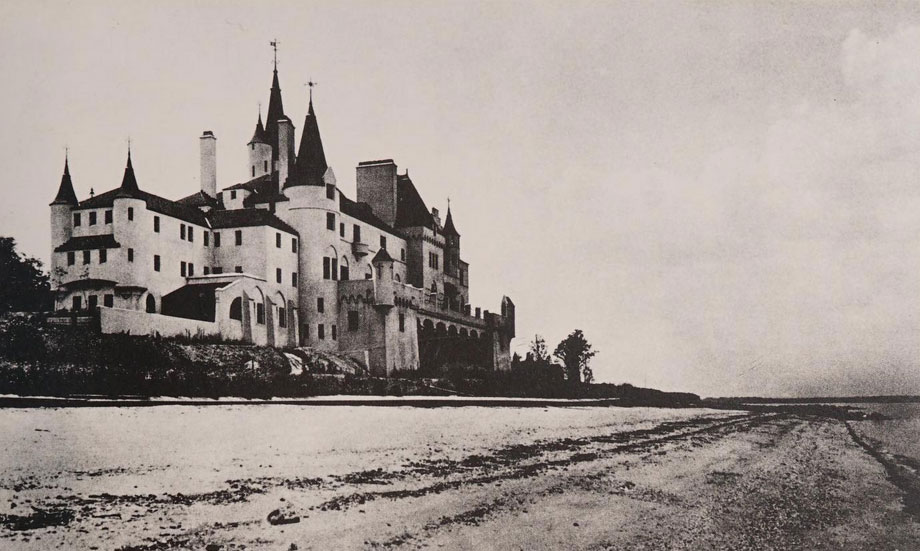

The interior of the house is no less grand. It has a “high Gothic library, panelled with carved English oak”, “Restoration Salons” and “Marie Antoinette music-rooms”. [3] The boyishly innocent but narcissistic Gatsby, the “ecstatic patron of recurrent light” stands before it in the gardens amongst the Jonquils and Plum Blossoms and smiles. “The grand life of the multi-millionaires all around went to his head”, wrote Shane Leslie of the short, exciting period in which he had introduced Scott to Long Island. And its not hard to see why. There were several houses like this in Nassau County at the time the novel was being written, but only one of them can really be linked to any one of the Gold Coast elites who personally knew Shane Leslie and that one is Beacon Towers — an enormous Gothic fantasy as audacious as it is preposterous. All that it was really missing was a moat. It was like something from the last crusades, a relic from the Middle Ages. According sketches found in the archives of architect Alfred Mizner, Belmont’s castellated chateau is also believed to have contained plans for a beach house. The idea was to build a one-room pavilion at the top of the cliff giving access to the beach and for the purpose of hosting tea parties — and perhaps not so unlike Nick Carraway’s bungalow.

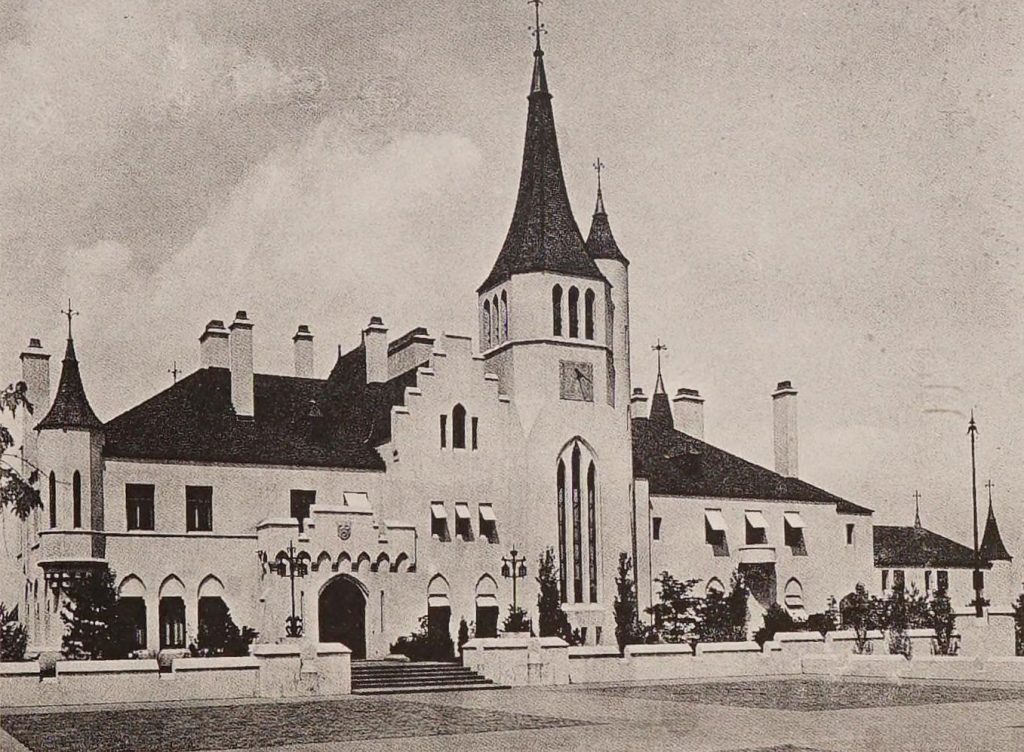

One man who would almost certainly have clocked Scott’s reference to ‘some Hotel de Ville in Normandy’ was his friend, Shane Leslie. To the vast majority of well-educated Catholics of this period there was only really one ‘Hotel de Ville in Normandy’ and that was the Abbey of Saint-Étienne in Caen. Leslie would have been perfectly familiar with both the Abbey of Saint-Étienne in Normandy and its ‘factual imitation’ in the Sands Point area of Long Island.

In real life, the ‘factual imitation’ on Long island was the home of Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, the indomitable former wife of William Kissam Vanderbilt who had built a scaled-down replica of the Abbey — the Gilded Age mansion, Beacon Towers — at Sands Point shortly after the outbreak of the war. Just across the bay was Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald’s brand new writing-base at 6 Gateway Drive, Great Neck. Leslie would have known all about Beacon Towers because Leslie was related to Alva. Just twenty years before, Alva’s society daughter, Consuelo Vanderbilt had married the 9th Duke of Marlborough, first cousin to Winston Churchill and also first cousin to Leslie. Alva had helped co-design the building with the legendary architect, Richard Morris Hunt. Hunt’s Châteauesque Style drew on the grand and gaudy designs of the Late Gothic period that defined French Normandy architecture [4]

Alva had purchased the 18 acre estate, adjacent to the Sands Point Lighthouse, in December 1915. Describing the house in his book The Vanderbilt Homes, Robert B. King writes that the desired effect was to “awe and overwhelm the eye”. The five-storey building rose from the beach of Long Island Sound “with no lawn to taper and balance its extreme height”. Because of this, the visitor was left with the impression of the building rising from the sea itself — not unlike a lighthouse. [5] But one thing it didn’t have, because it certainly wasn’t in keeping with the Gothic design, was marble. The marble steps, marble swimming pool, lawns and Marie Antoinette Rooms that we learn of in the Gatsby novel appear to have been spliced into the book from Alva’s ‘Marble House’ property in Newport, Rhode Island, also designed by Hunt and which, like Rosecliff, also incorporated elements of the Petit Trianon in Versailles. This last feature is not a coincidence because at 596 Bellevue Avenue, Alva Belmont’s more stylish neo-classical mansion can be found literally next door to the no less colossal Rosecliff estate used in the 1974 movie starring Redford. In the grand hall of Alva’s Newport property, Hunt had specially imported marble from Caen, home of the imitation abbey.

It’s at this point in time that the novel is gripped by a queer sense of coincidence or synchronicity. Something of a collision takes place between Scott’s Long Island adventures with Leslie and James Joyce’s Ulysses novel. The inspiration for the house is one thing, but what was the author driving at when he wrote it? What many readers don’t know (and what many critics tend to forget) is that Scott, had been born into a devoutly Catholic family in the Midwest town of Saint Paul at a time when the Catholic faith was bowing to increasing pressure to ‘Americanize’ its practices. The church in America was becoming split between those who wanted to modernise the church’s teachings and reaffirm its loyalty to the American flag and its much cherished Republican ideals and constitution, and those who wished to maintain the authority and influence of Rome. The scale of the tensions was such that in 1899, Pope Leo XIII, issued a formal decree suppressing ‘Americanism’ within the church as a heresy. The movement’s foremost modernizer was John Ireland, the Bishop of Saint Paul, a man who maintained close associations with Scott’s family on his mother’s side, the McQuillans. To understand the full extent of its influence we need to dig a little deeper in to the history of Beacon Towers.

St Stephen in West Egg

As we’ve just learned, the actual Hotel de Ville in Normandy that Alva based her Sands Point dream-build on is also known as The Abbey of Saint-Étienne, a Cinderella palace of Catholic origin that is alleged to have been built by William, the Duke of Normandy as he attempted to repair relations with Pope Leo IX in the aftermath of a disputed marriage. [6] The abbey is dedicated to the first Christian martyr, St. Stephen (Saint-Étienne). Scott mentions St Stephen in his first novel, This Side of Paradise. Amory’s Princeton roommates are quizzing Burne Holiday about his anti-war activities and ridiculing his preparedness to go down as a martyr. Holiday remarks that this was probably what ‘Stephen’ must have thought shortly before preaching his sermon and being stoned to death. [7]

The martyr’s connection to Joyce is a strange one, so you’ll have to bear with me on this. If you haven’t read Ulysses or its predecessor, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, it would be virtually impossible for anyone to have made the connection, but the central character in both of these novels is Stephen Dedelus, whose name is a juxtaposition of St Stephen (Saint-Étienne) and the legendary Greek artificer, Daedelus. The symbol of man’s creative triumph over the world of nature, Daedelus is the creator of the ‘great labyrinth’ that Scott refers to in the comparison he makes between himself and Goethe in his first novel, This Side of Paradise. The legendary Greek artificer is a figure who, symbolically at least, is not a million miles away from Jay Gatsby. He is someone who flies like a giant butterfly beyond the usual constraints of nationality, class and religion to triumph over the world of matter and win his freedom. For Scott, the fact that the parish of St. Stephen in Washington DC was also the first parish assigned to his mentor and friend, Father Sigourney Fay after the priest’s conversion to Catholicism in 1908, may have made the symbolism, perhaps missed on Alva Belmont herself, a little too tempting to let pass. Both men were martyrs of sorts; St. Stephen on account of his faith, and Stephen Dedelus as a result of the persecution he suffers for making any attempt to transform the “daily bread of experience” into art. Just as Joyce had forged his literary equivalent in Stephen Dedelus, Fitzgerald would, and in spirit at least, reinvent himself as Gatsby, another “priest of eternal imagination” who had sprung from his own Platonic conception of himself — and likewise a ‘son of God’. [8]

Articles written for the Dublin Review, where Shane Leslie served as editor, regularly mentioned the Abbey of St. Stephen and its status within the history of Catholic martyrdom, so it’s entirely conceivable that Leslie’s had discussed its origins and symbolism with Scott as they attended parties and satisfied invites from the Cockrans and his various Sands Point neighbours. [9]

Alongside Rosecliff’s owner, Theresa Fair Oelrichs, Alva’s neighbour (Leslie’s sister-in-law) Mrs Annie Bourke Cockran comprised the backbone of the Long Island Women’s Suffrage movement formed under the direction of fellow Sands Point resident, Harriett Laidlaw and the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Marie Antoinette had become something of an icon among the progressive and formidable women of Long Island. That Gatsby has a room in the house dedicated to Antoinette — just as Alva did at Marble House — reveals just how feminine Gatsby’s house is for a rough young bootlegger. Was this proof of the extent to which the house had been purpose-built for Daisy or, as Greg Forter suggests in his book, Gender, Race, and Mourning in American Modernism, evidence of the novel’s “empathically lyrical and implicitly ‘feminine’ expressiveness”? [10] With the exception of Gatsby, Nick, Daisy and Tom the character who makes their presence felt more than any other is a kind of ‘feminine other’. The moon which rises on practically every occasion in which Gatsby makes his appearance, is traditionally a feminine symbol most closely associated with capriciousness or impermanence. This would have suited Alva Belmont perfectly. In June 1922, the same month and year that Gatsby is set, Belmont was expressing her wish to see a woman in the White House. Talking to the Bridgeport Times on the summer solstice, Alva explained that the only qualifications needed to get the job done were ability and integrity.

Readers will find references to the moon peppered throughout Gatsby. It’s there shining its “wet light” on the tangled clothes of the 17 year old James Gatz as he undergoes his metamorphoses into Jay Gatsby, it’s there when Jay makes his entrance at the party, it’s there rising as Nick encounters Gatsby in his garden after the crash that kills Myrtle, and it’s there rising again when Nick visits the house for the very last time after his death. In Christian mythology however, the moon is most closely associated with Christ. It symbolises his light and life. It’s for this reason that Easter always falls without fail on the first Sunday after the paschal full moon. The resurrection is based on moon cycles. [11] Nick leaves West Egg for good around the time of the Full Moon in November. In some regions of the world, people will know this moon as the Beaver Moon, some as the Frost Moon, and some as the Mourning Moon. Its appearance in the sky at the end of autumn is usually an indication that the world is cooling, a time to for trees to let go of their leaves and a time for people to let go of the past.

A Jesus of the Planets and Stars

For almost a century critics have wrestled with Scott’s presentation of Gatsby as some kind of martyr or Christ figure sacrificed at the altar of excessive materialism. More often than not though, the theory is pinned almost exclusively on the reference to Jay being ‘the Son of God’ and the almost casual remark about the “holocaust being complete” after Jay is shot dead by the distraught husband and garage-owner Wilson in the final chapters of the novel. And whilst there’s no way of knowing for certain whether Scott consciously drew up on the historical links between The Abbey of Saint-Étienne and Alva Belmont’s gaudy and palatial mansion at Sands Point, it’s certainly a curious twist of fate. Saint Stephen appears twice in his first novel: first as the inspiration for the name of Amory’s father , Stephen Blaine (p.93), and somewhat later in the novel when Burne Holiday compares his pacifist stance to the heroism that Stephen would have shown shortly before being stoned to death (p.136).

The rather narrow coming-of-age scope of Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist and Fitzgerald’s uniquely American counterpart, This Side of Paradise, was obviously broadening into something a little more epic for both men. Joyce had followed his literary debut with his sprawling 700-page telephone book of a novel Ulysses, whilst Fitzgerald had pursued the same epic intent within the more and elegiac format of Gatsby And whilst the 150 page novel may not go out to shock with the same aggressive disregard or abandon as Joyce’s 700-page improvised explosive device, it still has a rebellious streak, gift-wrapped though it is as a romance. To have Gatsby build a factual imitation of the Abbey of Saint-Étienne in the garish new money paradise of West Egg is the most poetic of profanities. Gatsby’s house was Gatsby’s temple, and in the most twisted of consecrations he was making his own flamboyant novena to himself and his own meretricious dreams. The reference may have been lost on most of his readers but among the more Conservative Catholics at home and in Europe it would have been seen as a provocative move. Having Gatsby portrayed as a sacrifice was one thing, but to call him ‘the Son of God’ was likely to have been viewed as a step too far. Contrary to expectations Leslie thought well of the book. A surprise indeed given that just three years before he had appointed Chamberlain to Pope Pius XI where he was probably using the considerable weight had among the influencers of Britain and America to find a solution on the problem of restoring an autonomous and independent Vatican State. [12] Leslie, however, would have troubles of his own the following year when he was forced to withdraw his semi-autobiographical novel The Cantab from sale after the Bishop of Northampton complained that the depiction of the flippant religious musings of Cambridge undergraduates in the book offended good taste and morality. [13] But that’s a whole other story and another series of sins entirely.

In the novel, Scott makes little effort to disguise the fact that Gatsby is being presented as a rebooted Christ-figure — an Alpha Omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end, who is and who was, the past and the future. This however is unlikely to have been a cause of offence in itself. The greater wrongdoing among Catholics is more likely to have been served by having the sports car driving, pink-shirted Prophet of the Jazz Age embracing the dawn of the post-war apocalypse with all the energy and all the gusto of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald downing their heels and upping their toes to George Olsen’s Varsity Drag. Gatsby is a crook at the start of the novel and a crook at the end of it. It’s not a story of redemption in the conventional sense of the word. It’s the story of a man who dies as much from his own disastrous vanity as from the crass and careless behaviour of others. Vanity, Vanity sayeth the Preacher. Futility, Futility sayeth the Teacher. [14] If any absolution at all is offered, it is offered only by Nick. Shouting from across the lawn as he leaves after breakfast, he makes his last farewell: “They’re a rotten crowd. You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together”. Flattered by Nick’s attempts to relieve his moral burden, Gatsby can only smile.

By the time that Fitzgerald had begun to sketch out the first ideas for Gatsby in June 1922, Scott wasn’t entirely finished with the Catholicism of his youth. June 1922 was the month of dreams as record numbers of Jews from Eastern Europe scrambled to safety across the Atlantic, the International Courts of Justice opened its doors for the first time at the League of Nations and the draft of the new Irish Constitution was made public on the eve of its first elections. The momentum of the war kept hurling the Free World forward. Those who embraced and supported change duly shifted into a new gear and those who resisted instinctively put it into reverse. Among those embracing the changes was Alva Belmont who would throw open the gates at Beacon Towers to immigrants seeking refuge on weekend retreats. It will of course come as no surprise to learn that the house also provided inspiration for MGM’s The Wizard of Oz.

Observing the mad, desperate race across the waves to freedom made by the Jews of Eastern Europe had reminded Scott of the journey his own grandfather had made from Ireland in his bid to escape the famines of the mid-19th Century. Scott found himself faced with a similar dilemma: he could cling to the past and face almost certain personal and creative death or row furiously into the unexplored territories of the future.

In his 1916 book, The End of a Chapter, Shane Leslie would find himself lamenting the huge sentimental losses that Europe was now facing as a result of the Great War. What we were witnessing was no less than “the suicide of the civilisation called Christian and the travail of a new era to which no gods have been as yet rash enough to give their name.” Scott would pick-out this phrase for a review of Leslie subsequent book, The Oppidan in May 1922, just weeks before starting work on Gatsby. The review went on to explain that there was in Leslie “a stronger sense of Old England” than was possessed by any other living man. Leslie had come into his life at Newman as “the most romantic figure” he had ever known.In Scott’s eyes, the man who hummed “the haunting melody of a great age” had made the Catholic church “a dazzling golden thing, dispelling its oppressive mugginess”. Scott went to explain how Leslies new book “shadowed tapestries of the past” with less romantic glamour, carrying you back to the Eton of Shelley. Casting a non-judgmental eye over the new sciences of men like H.G Wells and the amusement parks of obscenity opened by writers like George Moore, Leslie had been among the first to acknowledge that there “arose a cry for the future instead of the past”. A love of chivalry had been replaced by a love of wonder. And whilst he neither blamed nor commended anybody specifically for its passing, his words, according to Scott at least, were marked a “mellow despair”. [15] And it’s this very same tension that defines Gatsby’s house: Gatsby, like Leslie, is a man out of time and the fairytale house that he lives in is a preposterous and romantic relic clinging like ivy to the crumbling grey walls of the past.

Nothing Fades as Fast as the Future. Nothing Clings like The Past

Sentimental efforts to bring more of the Olde Worlde back into the New World are nowhere better illustrated in the novel than in the story of the brewer who had built Gatsby’s house originally. The story told by Nick in the book is that the brewer had agreed to the pay five years of taxes on the neighbouring cottages if the owners would agree to having their roofs thatched with straw. The offer was said to have been made during a ‘period craze’ a decade before. A look through the newspaper archives of the 1912-1913 period reveals that there was indeed a craze for straw thatched roofs in the Sands Point and Great Neck areas at this time. One story in The New York Times dated October 1912 reviews these nostalgic affectations as they were taking shape at Westbrook and Castle Gould where the architect, Richard Morris Hunt had been commissioned to design an exact replica of Kilkenny Castle in Ireland. [16]

Across the Sound at Great Neck, another thatched haven was being revived, this time by the owners of ‘Grenwolde’, a waterfront estate being developed by Edward King whose residents would eventually include Scott’s movie-mogul friend, Sam. H. Harris and the actor Ed Wynn. In August 1925 Scott’s friend, Ring Lardner wrote to him in Paris to tell him of a riotous 4th of July firework party Wynn had hosted at his home in the ‘Grenwolde division’: “All the Great Neck professionals did their stuff, the former chorus girls danced, Blanche Ring kissed me and sang The part lasted through the next day”. He ends his letter by telling him that Charlie Chaplin’s new picture, The Gold Rush — a more comedic satire on the pursuit of the American Dream — had just opened in New York. An advertisement for the estate published in April 1913 describes how Grenwolde’s half-timbered houses were “modern adaptations of the always charming thatched cottages” of rural Britain. As if the point being made wasn’t persuasive enough, the word ‘Grenwolde’ had even printed in bold-type Gothic font. [17] As Tony Tanner writes in his 1990 introduction to The Great Gatsby, the “desire to affix a prestigious patina of pastness to a less obviously distinguished present” was leading to more audacious designs, more cringe-worthy affectations and, worse still, more anti-progressive longings.

Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man had prepared the way for Scott’s first novel, This Side of Paradise. Ulysses would cast a similar spell over The Great Gatsby, but in a completely different fashion. Both books tell epic tales of ordinary men made grea only by virtue of the fact that their stories are being told. This time Scott was not so much mimicking Joyce’s impact at the level of literary form but at a cultural level. America had reached a literary and moral crossroads. The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice — a kind of literary Inquisition — had stepped up their campaign of censorship against the Modernists. Although Ulysses would only be published in its entirety in Paris in February 1922, a number of extracts from the novel had been appearing for several years in Margaret C. Anderson’s Greenwich Village-based journal, the Little Review. The Vice squad had responded with a fierce high-profile court case to get it banned. That case had been partially settled in 1921 but by the time that Scott started work on Gatsby, Ulysses was back in the news again, as was a new translation of Petronius’s The Satyricon, whose racy Rabelaisian take on the rags to riches story of the Roman slave Trimalchio had given The Great Gatsby its original working title. The Satyricon had it all: sex , money and the most riotous of all-night parties. Scott had an idea: the story of Trimalchio could be re-booted for modern times. All he had to do was let go of his past and his dependence on the faith of his youth. Shane Leslie had described Ulysses as an “an indulgent stab at scandal”, an “Odyssey of the Sewer” [18]. But more importantly perhaps, everyone was now talking about it. Scott’s third novel would be the literary equivalent of a seismograph, recording the shock-waves generated by Joyce’s book and transmuting them first into art and more importantly, into profit. A little controversy could go a long way, and Fitzgerald knew this. Yes it was intended to shock, but it was intended to shock quietly. If he pitched this book correctly it would escape the wrath of the censors and any commotion that it engendered would, God willing, translate into sales of the novel — and quite possibly, some level-headed discussion about censorship.

The tarot card had been turned. It was an upright Simon Magus: the priest of eternal imagination, exchanging his spiritual assets for temporal goods, the love of God for the love of the silver-dollar. Scott was on the lookout for something bright, shiny and new that would dazzle more than Fay, and outshine any amusement park on Coney Island or any World’s Fair, for that matter.

[1] ‘Some Memories of F. Scott Fitzgerald’ Shane Leslie, Times Literary Supplement, October 31 1958, p. 632

[2] The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald (1920), Penguin, 1990, p.10, p.11, p.46, p.51, p.88. Scott would have encountered their symbolism in the work of Percy Bysshe Shelley (‘Epipsychidion’) and the Romantic poets.

[3] The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald (1920), Penguin, 1990, p.10, p.11, p.46, p.51, p.88.

[4] Hunt’s Châteauesque Style would typically feature include steeply arched-roofs, turrets, round conical towers. You will find the same style popular among the baronial castles of Scotland. Hunt had studied in Paris.

[5] The Vanderbilt Homes, Robert B. King, Rizzoli, 1989, p. 166

[6] Its French name is the L’Abbaye-aux-Hommes. In later years it was attacked by the Protestant Hugenots.

[7] This Side of Paradise, F. Scott Fitzgerald (1920), Penguin Modern Reader, 1996, p.136

[8] ‘Daily Bread of Experience … Priest of Eternal Imagination’, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man’, James Joyce, 1922, Penguin Classics, 2003, p.240; ‘Platonic conception of himself’, TGG, p.95

[9] The Dublin Review, July 1917, Vol. 161. No. 322, p.18

[10] Gender, Race, and Mourning in American Modernism, Greg Forter, Cambridge University Press, 2011, p.53. I personally don’t consider Gatsby to be a feminist novel, but there’s little doubting the femine imagery and spirit that drives its narration.

[11] The first full Moon after the spring equinox.

[12] Shane Leslie to Scott Fitzgerald, April 3, 1922, F. Scott Fitzgerald Papers, Princeton University, Box 46, Folder 17 – Leslie, Shane (C0187). The Lateran Treaty of 1929 which created ‘Vatican City’ accepted a solution rejected by the Itlaian Senate in 1872. Pope Pius XI replaced Benedict in June 1921.

[13] ‘New Book to Be Stopped’, Westminster Gazette, March 13, 1926, p.12

[14] Ecclesiastes 12:8

[15] The End of a Chapter, Shane Leslie, New York, C. Scribner’s sons, 1918, Preface; ‘Homage to the Victorians. The Oppidan’, New York Tribune, F.Scott Fitzgerald, May 14, 1922, p.8.

[16] Hugh Estates near New York make it rival London’, New York Times, October 13, 1913, p.11. Hunt had been commissioned to build Castle Gould by Howard Gould, the son of ‘Robber Baron’ and railway magnate, Jay Gould. His actress wife (of Jewish and Irish heritage) was rumoured to have had an affair with Buffalo Bill.

[17] ‘Grenwolde’,Waterfront Property, Great Neck, New York Times, April 6, 1913, p.5.

[18] ‘Ulysses’, The Dublin Review, Domini Canis (Shane Leslie), July-September 1922,Vol. 171 No.342, p.119

© Written and researched by Alan Sargeant, 2022.