Max von Gerlach, an associate of gangster Arnold Rothstein and author Scott Fitzgerald, made regular trips to Havana. At one time, Havana was also the home of Francis Cugat, the Spanish-Cuban artist who designed the famous dust-jacket for Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel, The Great Gatsby. Here we explore the possibility that it may have been Gerlach — believed by some to be the inspiration for Jay Gatsby — who first introduced Scott to the artist.

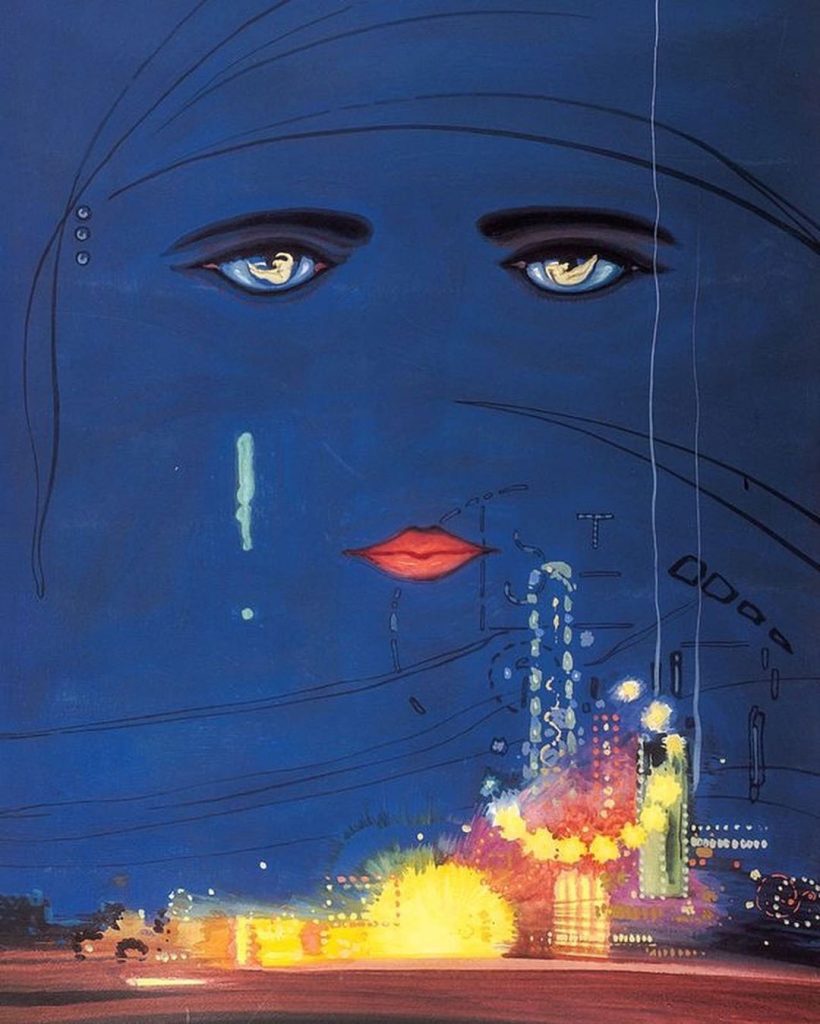

In 1924, Spanish-Cuban artist, Francis Cugat submitted several surreal drafts of an idea he had for the dust-jacket of The Great Gatsby to Scott’s publisher, Charles Scribner Son’s. The art historian Charles Scribner III, a close relation of the company’s founding president, remarked in his essay, Celestial Eyes: From Metamorphosis to Masterpiece, that Cugat was not a regular contributor to Scribners and that nobody seemed to have any idea who commissioned him. If you haven’t seen this now legendary first edition cover you will find that it features two large, faceless eyes staring out above a New York Skyline. It’s night, a time of mystery. The eyes, which are angled down at the gentlest of degrees, are looking at us. They belong to a woman, possibly Daisy, and they make a forlorn, ethereal appeal to the eyes of the viewer. Painted almost imperceptibly into the pupils of the eyes are male and female nudes — partly-classical and partly-erotic and vaguely hinting at the Epic-Heroic fantasies of the ‘great’ man himself. Exploding like fireworks in the scene below are the bright lights of the Coney Island amusement park, the compelling yellow glare of the Ferris Wheel dazzling the eyes like a beacon, the soft weeping blues of the night a melancholy reminder of love’s losses. Looking at the cover gives us a glimpse of how Gatsby might feel. The thrills of the park below are transitory at best. You can look but you can’t fully engage — it’s too far away. It’s a joy observed but not experienced. All that remains is the glow of the joy that the park promises. It’s how a child might feel standing by watching others play. It’s portrait of detachment, a moment of forbidden, unspoilt pleasure frozen in time.

Cugat was never mentioned in any of Scott’s letters, nor was he mentioned in any correspondence that his editor, Max Perkins, shared with Scribner. Nobody knows when Cugat was hired. Nobody knows why he was hired. His appearance in the story is as soft and disembodied as those two large eyes he painted looking out above the New York skyline. The Great Gatsby is composed of all kinds of ephemera and Cugat is just one passing ghost among them. Cugat’s painting appeared on the first printing of the book in 1925 and was never used again in Scott’s lifetime. His sketches of other ideas, like smoky dust plumes and heaps of ashes, suggest a familiarity and emotional connection with the novel that would have been quite extraordinary at that time. As Charles Scribner III observes in his essay, not even Scott’s editor Max Perkins got to see any of Scott’s manuscripts until November 1924 — some six months after Cugat had begun work on the paintings. Max had the basic idea of the story and a variety of possible titles, but precious little else. Scott was keeping the book tightly under wraps, promising him that unlike his ‘trashy’ stories for the magazines, it would be a “purely a creative work” showing the “sustained imagination of a sincere and radiant world.” [1] How was Cugat able to evoke the central themes and metaphors of the novel so sensitively, and so precisely, when not even Scott’s publisher knew much if anything about it?

August 27, 1924 — some eight months ahead of publication — found Scott in an excitable state. Earlier that week he had received a copy of Cugat’s gorgeous gouache painting. He was over the moon with the cover. “For Christs sake don’t give anyone that jacket you’re saving for me. I’ve written it into the book,” he screamed at Max. [2] As we seen already, author’s biographers have tied themselves in knots over the issue, some even going so far as saying that Scott’s inspiration for the haunting billboard eyes of Dr T. J. Eckleburg had come directly from Cugat’s painting, partly because Scott had confided to Max that he had written the two large eyes into the novel, and partly because Cugat seems to have been connecting with the unfinished novel in the most unusually prophetic of ways; not only did Cugat manage to produce a surreal approximation of the iconic billboard image, he also had the foresight to include the amusement park Ferris Wheel that Scott had featured in his discarded prologue to the novel. But just how did he know about any of this? [3] In the absence of any further information to go on, Scribner Jnr had very little option but to conclude that “credit might go to some anonymous angel in the Scribner art department”. [4] It was the work of fairies, or so he believed.

The truth, however, might be a little different. What if Cugat had information about the novel that not even Scott’s editor, Max Perkins, had been aware of at that time? Contrary to newspaper reports, Francis Cugat was not strictly a ‘Spanish painter’. He was a Spanish-Cuban painter, whose family had fled to Havana at the turn of the of 20th Century. This is where Max Gerlach comes in. For anybody who doesn’t know, Max Gerlach was the Long Island bootlegger with a phony Oxford accent and the ‘Old Sport’ salutation that Scott appears to have known in Great Neck during the 1922 to 1924 period. To respected academics like Professor Horst Kruse he was the original Jay Gatsby.

We don’t really know a great deal about Gerlach. We know that he managed a Speakeasy for Arnold Rothstein next door to Plaza Hotel on West 58th Street — where several critical scenes in the novel are set — and we know that he adopted the mannerisms and dress code of an Old World aristocrat. [5] We also know that for the best part of fifty years Gerlach had been making regular trips to Cugat’s hometown of Havana. According to a story published in the San Francisco Call in April 1950, ‘Baron Max von Gerlach’ had arrived in Havana, Cuba with “the eccentric Hallam Keep Williams”. Despite the report being no more than 40 words in total, the newspaper had a bombshell claim: the 65 year old Gerlach had been the original inspiration for the hero of The Great Gatsby and Williams was going to write a book about the Baron “that would top Fitzgerald’s famed work”. [6] Just a few before, Zelda Fitzgerald had told Princeton scholar Henry Dan Piper that a man they had known as “von Guerlach” had been the inspiration for the novel’s hero. [7] According to research by Professor Horst Kruse, Gerlach had first arrived in Cuba in 1906 and returned to the country at intervals for the remainder of his life.

In light of Gerlach’s regular trips to Havana in the twenty year period leading up to Gatsby’s publication — and in light of the fact that Max Gerlach appears to have known Scott well during this period — is it just possible that the man responsible for commissioning the project was none other than Gerlach himself? Perhaps Gerlach had introduced Scott to Francis and shown him some of his paintings? Scott, observing the surreal, ethereal quality of Cugat’s work and appreciating the artist’s haunting, dreamlike imagery, might well have been struck by just how well it matched the themes of his new novel and have asked to be put in touch. An exhibition of Cugat’s painting had been organised at the Anderson Galleries on Park Avenue and his imaginative landscapes, and fantastic portraits of ‘greats’ like Ludwig van Beethoven were gaining a considerable amount of attention. The gallery, situated on the corner of Park Avenue and 59th Street was managed by the fabulously daring publisher, Mitchell Kennerley, whose sensational bid to smuggle copies of James Joyce’s Ulysses — banned in America at that time — had made him something of a folk-hero among riotous young Modernists like Scott. The plot, hatched in the spring of 1922, featured Greenwich Village bookshop owner, Sylvia Beach and the Captain of a Transatlantic Ocean Liner. The plan was to smuggle 25-30 copies of the book a month from London to New York. [8] The gallery, which doubled as an auction room, occupied the clubhouse of the Arion Society, a Germanophile musical organisation that disbanded after pressure over the war. Mannerley once likened it to a “spiritual Monet Carlo”. The rich came here to get richer and the poor were made poorer for what they had to sell. It was there to help everyone, sellers and buyers alike. [9] In May 1920 it was reported by the New York Sun that over 60 lots of furniture owned by Kaiser Wilhelm were being sold-off in the galleries. Although an embargo usually forbade such exports, the collection’s agent, Vaidemar Poveleen was able to secure a permit on a promise that the proceeds of the Kaiser’s ‘throne room’ would be donated to a German relief fund. [10] In a letter to his editor, Max Perkins, just weeks after Gatsby was published, Scott had joked that if Scribner’s weren’t able to sell more 100,000 copies of the novel he would “shift to Mitchell Kennerley.” [11] Shortly after the exhibition, Scott’s play The Vegetable would makes it debut. Perhaps during one of his many visits to the city for the rehearsals Scott had strayed into the gallery and been dazzled by one of his paintings.

The “flattering introduction” to Cugat’s gallery catalogue had been written by the indefatigable New York columnist, Zoe Beckley, a friend of H. L. Mencken and the only journalist to have ever been granted an interview by Gerlach’s speakeasy godfather, Arnold Rothstein. Her praise for the young artist was reprinted in the New York Times: “Francesc Cugat brings you into, the luminous realm of color, sound and movement,; In all his pictures one ‘finds .the fantastic; poetic beauty of a rich imagination, a keen emotional and visible sensibility.” In 1939, Beckley would be living just five minutes’ walk from Gerlach’s apartment on Jones Street, Greenwich Village. [12]

Mutual Benefits: A Night at the Opera

By the time that The Great Gatsby was published in April 1925, Francis was working as set designer in Hollywood. Prior to this he had worked for several years as an illustrator for Cleofonte Campanini’s Chicago Opera Company and the Metropolitan Opera Company in New York — then under the patronage of the German-born philanthropist, Otto H. Kahn. The work had come off the back of his poster work for the Mutual Film Corporation of Chicago — the studio behind the world-famous Charlie Chaplin — the highest paid entertainer in the world at that time. [13] The work that Francis produced for Mutual was carried out by the Greenwich Litho Company of New York. The company, which features in Cugat’s US draft papers in 1917, was owned by Chicago-Buffalo businessman, Freeman Worthing Butts — or ‘Worthy’ Butts as he was known to friends. Interestingly Butts, a film and car pioneer, was a cousin of Major Archibald Butt, the military aide of President Taft who went down with the Titanic in April 1912. [14] At the time of the tragic incident, Butts was on his way back from Rome where he had been tasked with negotiating a settlement over disputed Catholic territories in the Philippines. The gallant major’s commitment to Spanish and Catholic affairs had similarly seen Butt dispatched to Havana in 1906 where he was put in charge of logistical operations and supplies in support of the US Military at its Ordnance depot in Havana. America’s efforts to restore order in the aftermath of the collapse of President Palma and Cuba’s first democratic government would subsequently become known as America’s Second Occupation of Cuba. The rebels were subdued and a provisional government was put in place. 1906 was also the year that future ‘ordnance’ officer, Max Gerlach, made his way to Cuba. Like Major Butt, the duration of Gerlach’s stay lasted from 1906 to 1908. [15]

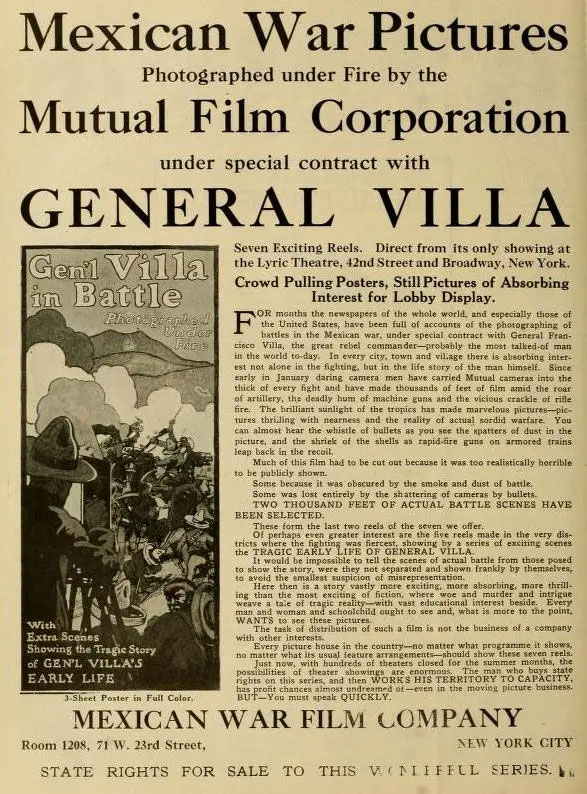

There’s an interesting crossover here. In 1914, the Mutual Film Company were paid by the Mexican Revolutionary General Pancho to produce a film of his life. The man who signed the deal with Villa was Hollywood legal counsel, Gunther R. Lessing. Some twenty years later Lessing would drag his Disney employers into a public relations nightmare when rumours began circulating that he had attended meetings of the German American Bund — a pro-Nazi organisation — among Disney employees. The lawyer, born the same year as Max, would travel to Mexico again in April 1919 and February 1921. [16] There was probably an element of quid pro quo in the arrangement with Mutual. By 1914 the number of theatres in Mexico was multiplying rapidly and American productions companies immediately saw the potential of extending returns in Latin America. Much the same agreement would be reached in Cuba during the 1940s and 1950s. As the US Cavalry pursued Villa and his men across Mexico, the New York Sun retold a thrilling account of Lessing’s bromance with General Villa and the support extended to him by Mutual Films. [17] Like Castro in the 1950s, Hollywood would present Villa as some latterday Robin Hood, shooting arrows on behalf of the little guy.

The film, The Life of General Villa, was a lavish propaganda exercise starring Villa as himself. The whole thing was carried out under the raw and innovative direction of a young Raoul Walsh, the eye-patched Irish-American who would go on to consolidate the career of another Cuban Rebel hero — the screen legend Errol Flynn. In 1959 Flynn would narrate Victor Pahlen’s Cuban Story: The Truth About Fidel Castro Revolution and release the self-penned drama-documentary, Cuban Rebel Girls. A film company, Exploit Films Inc was set-up specifically for the project. Supported by Brooklyn-man and distributor, Joseph Brenner, the actor and his pilot and manager, Barry Mahon, a former US flying ace and war hero, used both films as vehicles to promote Castro’s ‘heroic’, but probably much misunderstood, 26th of July Movement. Flynn had been a regular visitor to Havana for many years. In 1946 the actor had followed Scott’s friend Hemmingway to the city, covering its ‘sin-spots’ and its war for the New York press. The entire project with Mutual Films had, by contrast, been financed and promoted by Villa’s specially-formed, Mexican War Film Company on West 23rd Street. The three sheet full colour poster set advertising the flick were most likely overseen by Francis Cugat, who by 1917 had been made chief poster designer at Mutual Films. [18] However, the company’s decision to film the movie would put them on a war footing with the censors. In 1915 Mutual Film Corp would take the Industrial Commission of Ohio to court. The court’s eventual ruling would have far-reaching consequences for the industry. The year following the company’s court battle, Gerlach’s passport pal in Berlin, General James A. Ryan would become the head (and founder) of the Military Intelligence Department in the US Expedition to subdue General Villa in Mexico. [19] Joining him in the hunt on the ground would be Scott’s brother-in-law, Captain Newman Smith. In light of the revolutionary principles adopted in Spain and Cuba by his father, Juan Cugat, one might well suspect that film was something Francis could connect with. Havana at this time was home to an efficient German and Intelligence Network and agents loyal to Villa in Mexico had made their way to Cuba to a broker a deal with supporters there. [20] Also making a trip to Havana that year was Francis Cugat and his father. [21]

Mutual Film Company 1914

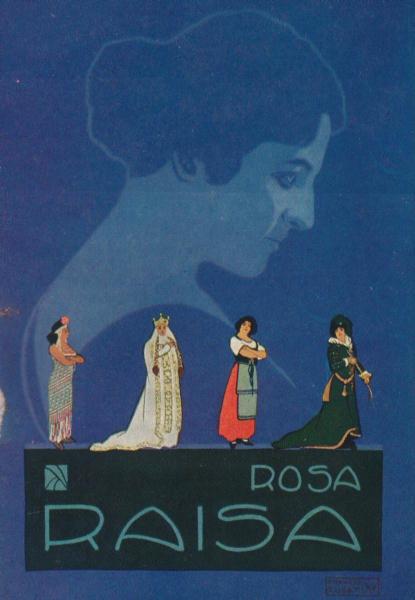

Cugat’s first opera subject in 1916, was Rosa Raisa, the Polish-born Soprano who had sang with Enrico Caruso. The artist’s work for Campanini and the Chicago Opera Company, which had appeared first in shop windows, had proved so successful that Cugat soon became a part of the company’s main publicity department. When Max Gerlach was in Berlin he appears to have been familiar with several female opera singers and musicians — among them Hallam Keep William’s mother, Alice Peroux-Williams and his SS Devonian sailing pal, Mary Louise Morrison. Furthermore, his 1939 hostess in Flushing was former opera singer, Lydia Lindgren, one of the most notorious American divas of them all. According to an interview that Lindgren gave to the Musical Courier in March 1916, she had studied under the great soprano voice coach, Selma Nicklass-Kempner in Berlin, only returning to America in August 1914 (SS Tyrolia). Gerlach was also in Berlin during the 1913-1914 period, although his activities there remain unknown.

By the time that Francis Cugat got his break designing posters for the Chicago Opera Company, Lydia Lindgren, was one of its most outspoken stars. In a press interview she conducted with the Boston Evening Post in September 1916, Lydia expressed her fondness for the works of Goethe and Nietzsche and the importance of sex in the women’s liberation movement. [22] Cast your mind back and you may just remember that in the late 1920s Lindgren had been embroiled in an ugly sex scandal with her friend and patron, Otto H. Kahn — the CEO of the Metropolitan Opera Company. More significant perhaps, is the fact that Lindgren’s first husband was Raoul Querze, the respected Italian voice coach who at just eighteen years of age trained the internationally famous dramatic tenor,’ The Great Caruso.’ [23] The young man accompanying Caruso on violin for Caruso during this time was none other than Francis Cugat’s younger brother Xavier, who would go on to become one of America’s most popular and flamboyant band leaders. [24]

Freedom Loving Exiles

Even if the chronology isn’t perfect, much of what happened in the early lives of the brothers can be gleaned from Xavier Cugat’s 1948 autobiography, Rumba is My Life. The brothers were born in Girona in Spain. After being jailed by Spain’s Royal Government for subversion, their father, Jean Cugat de Bru, a rebellious anti-monarchist with a talent for electrics, came under increasing pressure to leave Spain and in 1900, the family fled to Cuba, finally settling in Havana as freedom-loving exiles. In his book, Xavier describes his father as a “vigorous disciple of democracy” who was constantly causing short-circuits and the blowing fuses of any regime that opposed his principles. He remarks that even his moustache shot upwards at the ends “sharp and defiant”. Supported by Dr Eugenio Sanchez de Fuente, Secretary General of the Cuban National Red Cross, Jean immediately got to work organizing ‘bicycle brigade’, a team of mounted-cavalry, drilled to perfection in matters of childbirth and emergency first-aid treatment, and managed with the assistance of the Pan-American Union. [25] According to Xavier, one of the few personal items his father had been able to bring out of the old country was his uniform and sword of the International Red Cross in Spain. [26] Within 18 months of Cugat’s arrival, Cuba would win its independence from Spain. In May 1902, the Republic of Cuba was born, taking her volatile place among the nations of Pan-American. Within a few years Captain Cushman A. Rice, the American friend of Gerlach who had helped liberate the country under Cuban Revolutionary, General Calixto García, would make his second home here. [27] A short time later, the opera houses, the cattle farms, the American millionaires — and the crime bosses — would all move in. By July 1902 Cushman Rice was telling American newspapers that opportunities for investments were ‘numerous’. Land was ‘cheap’ and the climate was ‘healthful’. [28] Pretty soon, the theatres and the tracks would become Havana’s biggest attractions — and Rice would become an influential, if slightly mysterious, figure in all of them.

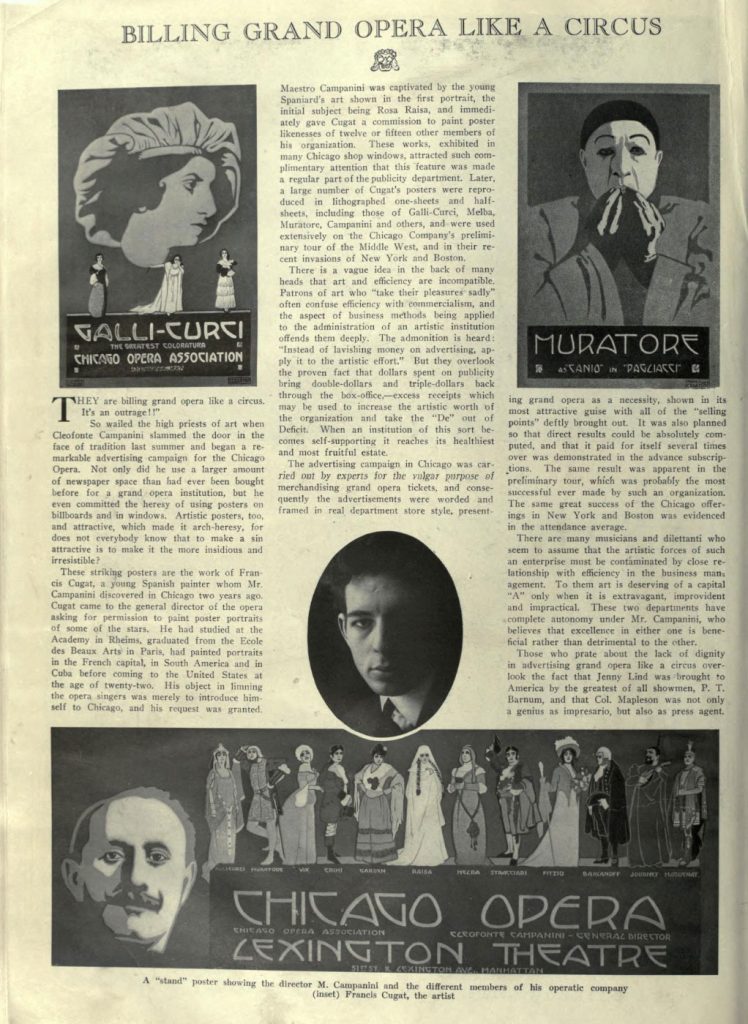

At some point in 1912, Francis, Xavier and their father Juan made the first of several trips to New York. [29] Despite news (from Cushman Rice) that Cuba was entering a ‘boom’ period, the family had been seduced by the all the glorious promises of the American Dream and were scouting for a new home in Manhattan. The arrival of successful US companies in Cuba had left little room for smaller merchants like Jean Cugat. Using funds secured from an exhibition given by Francis in Paris, the family book tickets on the SS Saratoga. The family’s first home was in Washington Heights — alternatively known as the Little Dominican Republic on account of its large, vibrant contingent of Spanish and South Americans. The banner of freedom was raised. Francis got a job in the art department at the Vitagraph Studios in Brooklyn — the film company whose footage in Havana of the Spanish-American war ranks as one of America’s first propaganda features — whilst Xavier was still at school. By this point in time both brothers had taken up painting, and although Xavier would remain a talented caricaturist all his life, he was a prodigious violinist whose fame had spread wide in Havana. According to Xavier, it was during this period that the family began to seek funds for the education of the brothers abroad. At some point between 1910 and 1919 Francis Cugat left New York to be tutored at the Beaux-Arts in Paris. A little later, Xavier was enrolled at the Conservatory of Music in Berlin, studying the violin under the ‘immortal’ Willy Hess and the renowned Karl Flesh. After studying Berlin, Xavier returned to Paris, sailing back at intervals to play brief, but noteworthy shows at New York’s Carnegie Hall. Having already been recruited on an ad-hoc basis by the Metropolitan Opera Company in Havana, Xavier continued to support their most famous vocal star, the tenor Enrico Caruso. His talented artist brother was also recruited by them, this time providing the illustrations that would accompany the programmes, posters and souvenirs promoting their famous opera stars. His work was not to everyone’s tastes. An article on Francis Cugat in the Theatre Magazine of January 1918 told how they were now billing grand opera “like a circus”. It was “an outrage!” they teased. The High Priests of classical theatre believed that Cugat’s posters were cheapening the art. There were many within the industry who thought that art and commercial efficacy were incompatible. Scott would encounter similar objections with his publisher, Scribner’s, which is probably why Cugat had been hired. As far as Scribner’s was concerned you couldn’t commercialize art. Scott had other opinions and would tell them so. In a letter dated April 1922 Scott sketched out plans for a budget collection of affordable but high-calibre reading matter, bound uniformly but with mass appeal. [30] As Scott saw it, making money from a book didn’t de-value art, it simply provided evidence that more people were enjoying it. Any additional monetary benefits brough about by commercial success could then be poured into maintaining and producing even better art. When it came to combining High Art with the bare-knuckle principles of popular advertising Cugat had a proven track record. He’d been able to mix it up already and as a result, had dramatically increased concert attendance. Scott was determined to create a product that could work simultaneously as highbrow literature and popular fiction — a novel that was custom-built for critic and consumer alike. Cugat was someone who understood that. [31]

Cugat’s big day came in June 1919 when the artist was commissioned to provide the graphics for lavish 64-page brochure that would accompany Caruso’s Silver Jubilee performance. [32] It was an important year for Caruso. Not only was he being recognised for his twenty-five year service to dramatic opera, he was also being honoured for the tireless work he had done for the war efforts promoting Liberty Loans. Over the course of the next few years Francis would also provide material for the Chicago Opera Company, whose most infamous star, Lydia Lindgren would open her Long Island mansion to Gerlach in the late 1930s. At this point in time Lydia was married to Raoul Querze, Caruso’s vocal trainer.

Shortly after Max returned from Havana in March 1920, Xavier and Caruso were caught in a crisis. On June 14 a bomb exploded in the city’s National Theatre. A short series of dates, organised by the Metropolitan Opera Company, saw the singer and his violinist trying to repeat the success of their earlier shows together. Caruso and Cugat were in their dressing room when the bomb went off. Mounting the stage they saw a large hole at the top of the proscenium arch — the great theatrical window that frames the stage. The orchestra made attempts to calm the audience with the Cuban National Anthem, but panic spread and the audience bolted for the exits in their hundreds. [33] Caruso would later ridicule the idea that the explosion had been meant for him but investigators were far from certain. Just several days before Caruso’s home in East Hampton, Long Island had been broken into and robbed. The thieves made off with over $400,000 worth of jewellery. It was his wife that was home at the time. A short time later Caruso’s Irish-American chauffeur, George Fitzgerald, who claims to have pulled out his revolver and shot into the dark in an effort to deter the robbers, was quizzed by Police. Caruso, still in Havana, came to the Fitzgerald’s defence, but subsequently terminated the man’s employment. [34] For a year or so, Xavier and Francis remained in Cuba before heading back to New York in 1921. By August, the Great Caruso was dead, the deluge of recent tour dates and events having had a devastating impact on his health.

The Times Literary Digest of April 12, 1919 included an extended feature on Caruso’s Silver Jubilee celebrations. Elsewhere in the magazine there was a small but significant tribute to others who had helped the war effort, among them Oscar E. Cesare, the Swiss-Italian caricaturist who appeared as beneficiary in the will of Gerlach’s first wife, Marie Lovell in 1912. [35] It is of course intriguing to note that Xavier Cugat had, like Cesare, initially earned his crust in New York as a caricaturist with several leading newspapers. Cesare would subsequently add his signature to the legendary pine ‘Red Door’ of Frank Shay’s bookshop in Greenwich Village — a door which many would come to regard as a lasting memorial to all the left-wing creatives who had passed through its doors during the 1915 to 1925 period. Above Cesare’s signature is the name of William Ely Hill, the man who designed the dust jackets for Scott’s first two novels, This Side of Paradise (1920) and The Beautiful and the Damned (1922). Another of the names on the door is Joseph Gollomb, the Russia-born husband of Cugat’s art champion, Zoe Beckley. The couple’s apartment at 45 West 11th Street was quite literally around the corner. In October 1922, a review of the riotous, bohemian antics taking place in The Village would appear in Harper’s Bazar. The satirical ‘graphic survey’ by Reginald Marsh of the Art Student’s League that would accompany the review featured Hill and Cesare appearing in doorways and falling out of bookshops as a truckload of ‘Young Intellectuals’ tore through Seventh Avenue on their way to a picnic. Among the figures depicted in the truck were Scott Fitzgerald and his friend John Dos Passos, Edmund Wilson and John Peale Bishop. For many years Cesare had been among an eclectic group of creatives who used to gather nightly at the Brevoort Hotel on Fifth Avenue. Among them were mystery writers, William Andrew Johnston and Arthur Somers Roche, a captain in the Intelligence Division of the US Army during the war. Roche’s immediate superior was Rupert Hughes, an ardent patriot and anti-Communist who had previously been involved in the hunt for Pancho Villa. In another scene in the graphic, Scott can be seen jumping into a fountain. ‘So this is Greenwich Village?’ giggled the headline.

In light of Gerlach’s ubiquity on Broadway (not always for legitimate activities) and his familiarity with several singing stars, the opportunities for Gerlach to have encountered Francis and Xavier Cugat are fairly substantial. The brothers could have met him in Havana — either around the concert halls or the bars — and then picked up their relationship in Manhattan. When Gerlach received his discharge from the army in 1919 he made almost immediately for Cuba, leaving in December 1919 and returning in March the following 1920 — just as Xavier Cugat and Caruso were taking up their residency in Havana. Caruso arrived at the beginning of May, whilst Cugat appears to have been in and out of the city for the past few years or more, returning occasionally to his family base in New York. [36]

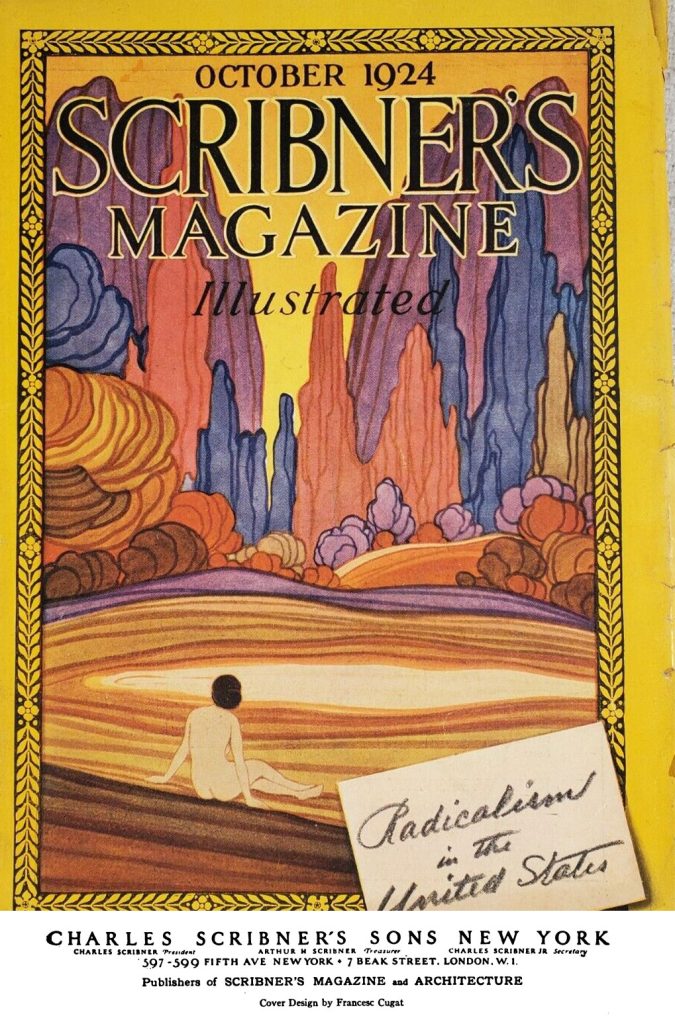

Scribner’s must have been impressed with Cugat’s work as just six months before his iconic dust-jacket found its way on to the bookshelves of America, another his illustrations — a surreal utopian dreamscape — was chosen for the October 1924 edition of Scribner’s Magazine. Previously overlooked by Scott’s biographers, this edition of the magazine featured an essay entitled Radicalism in America by Edwin W. Hullinger, a correspondent with the United Press who had visited Russia in the aftermath of the revolution. [37]

A Tale of Two Elenas

By 1924 there was someone else in Gerlach’s life. According to research undertaken by Professor Kruse, the manifest for a return trip from Havana in 1924, sees Max travelling with the 24 year-old Elena Gerlach. Kruse infers that this is his wife but a trawl of US marriages during this period refuses to throw up any useful match. As the name is predominantly used at this time by young Mexican women, it just might be possible that Max got married in Mexico or in Cuba sometime during the 1920 to 1924 period. Although Kruse records that Elena uses Huntington as her place of birth (either Huntington Long Island, or Virginia), a similar trawl through birth records during this period similarly draws a blank. According to birth collection held online there were only a handful of people born with the name Elena in the United States between 1898 and 1902 period — all clearly of Spanish heritage. [38] They appear to belong to two families in all: one family in Wisconsin and the other one in Rhode Island (suggesting a tiny enclave of Mexican families in each). Factor in the number of illegal immigrants from Mexico and Cuba (and the number is likely to have been large) and it might that Max’s wife had arrived during the mass arrival of Mexicans from 1910 onwards.

There is however another possibility. In 1929, Xavier Cugat married opera star, Carmen Castillo. But this was only her stage name. Her real name was Elena Castilla. Elena had arrived in New York from Vera Cruz in Mexico in 1919 aboard the SS Monterey. It was only in 1927-28 that Elena Castilla became Carmen Castillo. Until this point in time she was plain old Elena, born like Gerlach’s wife in 1900. Even if there if the two Elenas have nothing more in common than their Spanish heritage and their age, it is curious to see the same uncommon name appearing twice in related circles. It is also interesting from a cultural point of view that in her earliest reports, Elena Castilla is presented as being Spanish and not Mexican — a change that may have been made in part because a sizeable part of the American media still treating them with prejudice. [39] According to Xavier, Castilla and her mother had a good rapport in Hollywood with several Cuban visitors, among them a young Manuel Benitez, in the late 1930s would be become General Manuel Benitez, head of the Cuban National Police, right-hand man to coup leader, Fulgencio Batista and good friend of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. Back in mid-1920s Palm Springs, Cugat and Carmen knew him as an eager Hollywood movie extra and although urban legend maintains that Fidel Castro appeared in one of Cugat’s later films, the greater likelihood is that it was his old friend Manuel Benitez. [40] When Scott’s friend (and his publisher’s other protege) Ernest Hemingway was running his private network of spies in Havana in the early 1940s, one of his tasks was to keep an eye on Benitez and Batista — generally regarded as self-seeking opportunists, so mixed-up in the affairs of the American Mafia that it was thought they could seriously embarrass America at any moment. [41] It may be worthwhile noting that it was Cugat’s friend, General Benitez who was found to be entertaining Gerlach-gossiper, Cholly Knickerbocker (Igor Cassini) during his visit to Havana in the early 1940s. After the Castro removed them from power, Benitez and Batista were offered temporary asylum in the Dominican Republic under the protective arm of Cholly’s 1959 sugar-daddy, Rafael Trujillo. [42] Benitez would eventually spend out his days his exile in Miami. In April 1961, Cholly Knickerbocker gave us on update on the ‘writer’ Hallam Keep Williams, when it was learned that Hallam’s son Turner from his marriage to Josi Johnson was about to start college.[43] What Hallam had been doing to maintain his profile in one of the most popular columns of its day remains unknown because he certainly wasn’t making the headlines. Maybe Cholly just had a soft spot for handsome playboys.

In the two or three years before he was commissioned to design the cover for Gatsby’s Francis Cugat appears to have left New York for Los Angeles where he began his work as a set-designer. On of his first jobs in 1922 was ensuring the authenticity of Mae Murray’s Metro production, Fascination, set in Spain. [44] By December 1925 he was working with Douglas Fairbanks Jnr. Interestingly, when Gerlach left his ‘Old Sport’ message informing Scott that he was on his way back from ‘the Coast’ in July 1923, the phrase was often used as short-hand for Los Angeles. Could it be that Gerlach had hooked-up with the Cuban brothers (and perhaps even Elena) as the brothers settled into their work in Hollywood? Sadly, like so many other things in Gerlach’s life, we may never know.

At the end of Gatsby there’s a scene in which Nick talks of the dreams he still has of West Egg. In these dreams, West Egg maintained the ‘quality of distortion’ that it possessed during Gatsby’s lifetime. Nick tells us that he sees it as a “night scene by El Greco”. It’s a reference to a Spanish painter that Francis and Xavier Cugat were particularly fond of. [45] In his dream there are multitudes of houses “at once conventional and grotesque, crouching under a sullen, overhanging sky and a lustreless moon. In the foreground of the picture he sees “four solemn men in dress suits are walking along the sidewalk”. On the stretcher they carry between them lies a drunken woman in a white evening dress. [46] The surrealist nature of the image, and the distorted and elongated shapes that haunt it, makes one wonder if Scott had based the passage on some discarded sketch for the novel by Cugat. If Scott, like so many scholars have suggested, had featured the artist’s ideas elsewhere in the novel, then it certainly wasn’t impossible for him to have secreted one final, surprising tribute.

© Alan Sargeant 2023

Special thanks to Dirk Soulis of Soulis Auctions for information on the Esslinger Trade Sign

[1] ‘Dear Max’, April 10, 1925, Great Neck, Dear Scott/Dear Max, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1973, pp.69-70

[2] Scott to Max Perkins, August 27, 1924, A Life In Letters, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Simon & Schuster, 1995, p.79

[3] In the book, Scott writes: “The eyes of Doctor T. J, Eckleburg are blue and gigantic — their retinas are one yard high. They look out of no face but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles.” Another critic has rightly pointed out that when Scott says he has written it into the novel he probably means the line: “Unlike Gatsby and Tom Buchanan, I had no girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs” which appears as Nick and Jordan head out of New York along Queensboro Bridge.

[4] Celestial Eyes: From Metamorphosis To Masterpiece, Charles Scribner III, Princeton University, Library Chronicle, Volume LIII, No.2, Winter 1992, pp.141-154

[5] In The Great Gatsby, Arnold Rothstein finds his fictional counterpart in Meyer Wolfsheim, Gatsby mentor. See: F. Scott Fitzgerald at Work: the Making of The Great Gatsby, Horst H. Kruse, University of Alabama Press, 2014.

[6] ‘Cholly Knickerbocker Observes’, The San Francisco Examiner, April 17, 1950, p.20

[7] The Far Side of Paradise, Arthur Mizener, Houghton Mifflin, 1951, p. 366

[8] Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation, Noel Riley Fitch, W. W. Norton &Company, 1983, p.121

[9] ‘A Statement by the Anderson Galleries’, New York Tribune, June 13, 1922, p.9

[10] ‘Kaiser Throne Room Fittings to be Sold Here’, The Sun and New York Herald, May 13, 1920, p.1

[11] ‘Dear Max, June 21, 1925’, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, bantam Books, 1973, p.193

[12] Exhibitions, Time, Vol. II, No.12, November 19, 1923, p.13; 1940 Census, Zoe Beckley, 95 Christopher Street, Greenwich Village; ‘It’s Brains Says Rothstein’, Zoe Beckley, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 27, 1927, p.14; ‘At the Anderson Galleries’, New Yor Times, October 28, 1923, p.12. Zoe Beckley (1875-1961). Beckley had worked alongside H. L. Mencken and John Reed at the New York Evening Mail. She was married to radical Daily Worker activist, Joseph Gollomb, born in St Petersburg, Russia, b. 1881 and author of the 1928 factual book, ‘Spies’ and the 1939, ‘Armies of Spies’. Like Cugat, Zelda Fitzgerald would also have her own paintings exhibited at the Anderson Galleries.

[13] ‘Chicago Opera Posters to be Designed by Film Company’s Expert’, Musical America, July 14, 1917, Vol.26, No. 11, p.2; ‘Chicago Opera Posters Show Good Taste’, Chicago Examiner, November 3, 1917, p.3. The posters for the Mutual Film company were produced by Greenwich Litho Co in New York. This company featured as Cugat’s employers in his 1917 draft papers.

[14] Mrs Butts May Get Decree, Washington Post, November 3, 1914, p.9. Butts was director of several lithographic companies and car garages. He was also a director at the Universal Film Company and several other studios in Los Angeles.

[15] ‘Application for Service US Army, Ordnance Department’, Scott Fitzgerald at Work, Horst Kruse, 2014, p.33; ‘Capt Butt to Leave Tonight: Will Proceed to Havana to Prepare for Arrival of Military Forces’, Washington Evening Star, September 29, 1906, p.1

[16] Gunther R. Lessing (b.1885) 1919/1921, Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925. Lessing’s father was born in Alzey, Germany.

[17] ‘Meeting Pancho Villa in the Days of His Glory’, New York Sun, March 26, 1916, p.3

[18] ‘Mexican War Pictures under Special Contract with Pancho Villa’, Reel Life, Mutual Film Corporation, May 1914, p.32. The deal was signed by Frank N. Thayer. also see: Filming Pancho: How Hollywood shaped the Mexican Revolution, Margarita de Orellana, Verso, 2009

[19] An intelligence report on Max Gerlach in June 1917 claims that Gerlach secured his passport back from Berlin to America in August 1914 from James A. Ryan, who assisted Ambassador Gerard at the US Embassy.

[20] ‘Plot to Estrange Villa and Caranza Reported’, Bridgeport Evening Farmer, January 21, 1914, p.2

[21] Francisco Cugat (b.1893), 1914, SS Saratoga, Havana to New York, New York City Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

[22] ‘Lydia Lindgren: Mezzo of Chicago Opera Company’, Boston Sunday Post, September 10, 1916, p.42; ‘Lydia Lindgren’, Musical Courier, 1916-03-23: Vol 72, No.12, p.53. Lindgren may well have been in Berlin during the 1913-1914 period, but she the exact dates of her arrival in America are difficult to resolve. Her training with Kempner Nicklass in Berlin appears to have been closer to the 1910-1913 period.

[23] ‘Lydia Lindgren: Former Opera Star May Sing Again’, Musical America, Oct 6, 1928, Vol 48, No. 25, p.25

[24] ‘Rumba Is My Life’, Xavier Cugat, S. Low, 1948

[25] Bulletin of the Pan American Union, Volume 34, Pan American Union, 1912, p.730

[26] ‘Rumba Is My Life’, Xavier Cugat, S. Low, 1948, p.30; Xavier Cugat, The Scribner Encyclopaedia of American Lives, V.II, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1998-

[27] Cushman A. Rice was among several figures who provided the bona fides for Gerlach’s army application in 1918 and a passport application in November 1919 (for Havana, Cuba).

[28] ‘Speaks Well of Cuba’, Cushman A. Rice, Saint Paul Globe, July 24, 1902, p.7

[29] New York City Passenger Lists, 1820-1957, Javier Cugat, Francisco Cugat (b.1893) and Juan Cugat (b.1870)

[30] A Life in Letters, p.56

[31] ‘Billing Grand Opera Like A Circus’, Theatre Magazine, May 1918, vol. XXVII, No. 207, p.278

[32] ‘To the Many Admirers of Enrico Caruso’, Metropolitan Opera House Grand Opera Season 1918-1919 Program, p.20. Francis would also design posters for Cleofonte Campanini. See Chicago Examiner, November 3,1917, p.22. ‘Chicago Opera Association contracted for the services of Francis Cugat’, Musical America July 14, 1917: Vol 26 Iss 11, p.2

[33] ‘Caruso Scouts Idea of Plot on His Life’, The Sun and New York Herald, June 15, 1920

[34] https://www.easthamptonstar.com/east-magazine-villages-arts/2020521/enrico-caruso-caper-1920

[35] ‘Some Cartoonists who helped win the war – caricatured by themselves’, The Literary Digest, April 12, 1919, p.16; ‘Caruso The Golden Voice Celebrates His Silver Jubilee’, The Literary Digest, April 12, 1919, pp.84-88.

[36] The US Census of January 1920 sees him living with his brother Francis and his parents at 344, 180th West Street.

[37] Scribner’s Magazine, Vol. LXXVL, No.4, October 1924. Hullinger’s essay writes of the post-Revolution hysteria in America.

[38] The number of Elenas increases substantially in 1910 when America began to experience mass immigration from Mexico. Until this point there had been much resistance to Mexican immigrants.

[39] ‘Coming Concert’, Coronado Eagle and Journal, March 13, 1928, p.4

[40] Rumba is My Life, Xavier Cugat, p.95

[41] Ernest Hemingway, Federal Bureau of Investigation

[42] In 1963, the Federal authorities charged Cassini (Cholly) with failing to declare himself as a paid agent for the President of the Dominican Republic, Rafael Trujillo. It is believed that Cassini had been using his family’s friendship with President Kennedy and his father Joseph to have the CIA suspend an assassination plot on Trujillo.

[43] Society News & Fashions, Philadelphia Inquirer, April 2, 1961. Cassini also updated us on Hallam ‘hanging up his Wall Street activities’ in his Cholly Knickbocker column in 1954.

[44] The Washington Herald, April 16, 1922, p.18/ Hamilton Daily News, December 7, 1925, p.15

[45] Rumba is My Life, Xavier Cugat, S. Low, 1948, p.78. Xavier possessed a number of original paintings by El Greco.

[46] The Great Gatsby, 1925, p.212.